by Matthew Orwat | May 12, 2016

Burweed, Soliva Sessilis. – Image Credit: Joseph M. DiTomaso, University of California – Davis, Bugwood.org. Creative Commons License

This spring, lawn burweed has been an especially noticeable problem in lawns. Extension offices throughout Northwest Florida have been fielding many questions and finding solutions to lawn burweed infestations!

On the top of my list of lawn related annoyances is stepping into a patch of burweed, Soliva sessilis, which is in the sunflower family and is also known as spurweed. The leaves are opposite along the stem and sometimes resemble parsley. The main ways in which burweed can irk the casual gardener are sticking to socks, sneaking in with the dog, or littering flower beds with its nuisance. It can also hide in the house and reappear when shoes are removed. This causes pain in both the foot and the ear.

Aside from herbicides, maintaining a healthy vigorous lawn will prevent weeds from taking over. If your lawn is reasonably healthy and only a few instances of this weed exist, try to mechanically remove them and encourage the lawn to outgrow them.

If cultural methods aren’t sufficient, science has given us several options to control this irksome pest. Herbicides containing the active ingredients dicamba, 2,4-D or atrazine are good at controlling burweed as a post emergence control when applied from December through March. Be careful to use reduced rates on centipede and St. Augustine lawns, and never use more than the labeled rate since injury can occur when using these products on these species. Later applications have less effect on burweed because as it matures it is harder to control. Additionally the burs, once present on the lawn, are hard to remove. As the daytime temperatures rise to 90ºF, some of these herbicides may cause lawn damage. Try to keep the spray residue outside of the root zone of desirable plants to avoid injury and always follow label directions.

Be aware that burweed reproduces by seed, so mowing it down will only increase the problem by burying the seed for fall germination. Although we are now in the month of May, control of actively growing burweed might still be warranted if it is still flowering and setting seed. As temperatures warm up burweed will die, as it is a winter annual. In cases where it is already dying, control is not warranted since the natural cycle of winter annuals is concluding.

If an infestation of burweed has occurred this year, take note. The best time to apply pre-emergent herbicides to control burweed is in October. A widely used preemergence product for burweed control is isoxaben, which is sold under the brand name of Gallery as well as others. It prevents the weed from emerging from the ground when it germinates and can be used on St. Augustine, centipede, bahia and zoysia lawns, as well as in ornamental shrub beds. In northwest Florida, this herbicide needs to be applied in October for best results. A second application later in the season might be warranted. For more information about control, please consult this excellent article on lawn burweed management.

The active ingredients mentioned above are present in a variety of ‘trade name’ products* available from your local garden center, farm supply or co-op. Be sure to read label instructions carefully and contact your local extension office for any assistance. I hope all the northwest Florida lawn managers prevent burweed during the upcoming fall so that lawns will be burweed free next spring.

Happy Gardening!

by Larry Williams | Apr 7, 2016

Watering to establish lawn

When watering to establish a lawn or when renovating (redoing, patching, reestablishing, starting over, etc.) a lawn, we normally call for 2-3 “mists” throughout the day for the first 7-10 days until roots get established. These are just 10 minute bursts. Then back off to once a day for about ½ hour for 7-10 days. Then go to 2-3 times a week for about 7 days. By then your lawn should be established.

Of course, if we are experiencing adequate rainfall, you may not need to irrigate. Rain counts. But in the absence of sufficient rain, you’ll need to provide enough water at the correct time to allow your new sod to root – hence, the above directions.

A well designed and correctly installed irrigation system with a controller, operated correctly, really helps to achieve uniform establishment. It can be very difficult or impossible and inconvenient and time consuming to uniformly provide sufficient water to establish a lawn with hose-end sprinklers, especially if the lawn is sizeable and during dry weather. Most people are not going to do the necessary job of pulling hoses around on a regular basis to result in a well established lawn.

There is no substitute or remedy for incorrect irrigation when establishing a brand new lawn or when renovating an entire lawn or areas within a lawn.

It would be wise to not invest the necessary time and money if the new lawn cannot be irrigated correctly. Taking the gamble that adequate (not too much, not too little) rainfall will occur exactly when needed to result in a beautiful, healthy, thick, lush lawn is exactly that – a gamble.

An irrigation system is nothing more than a tool to supplement rainfall. As much as possible, learn to operate the irrigation controller using the “Manual” setting. It is also wise and is state law to have a rain shutoff device installed and operating correctly. The rain shutoff device overrides the controller when it is raining or when sufficient rainfall has occurred. Rain shutoff devices are relatively inexpensive and easily installed. Also, a good rain gauge can be an inexpensive tool to help you monitor how much rain you’ve received. Rain counts.

Too much water will result in rot, diseased roots and diseased seedlings and failure. Too little water will result in the sod, seedlings, sprigs or plugs drying excessively and failure to establish. The end result at best is a poorly established sparse lawn with weeds. Or complete failure.

For additional information on establishing and maintaining a Florida lawn, contact your County UF/IFAS Extension Office or visit http://hort.ufl.edu/yourfloridalawn.

by Beth Bolles | Mar 28, 2016

The mining bees or adrenids are often seen in areas of landscapes that have little ground vegetation and loose soil. After mating, the female bee will excavate a very small tunnel in the ground that has several small cells attached to it.

Beneficial solitary bee mounds in the ground. Photo by Beth Bolles

The bee collects pollen and nectar to add to the cell and then lays a single egg in each cell. The emerging larvae feed on the nectar and pollen until it changes to an adult bee in the fall. There is only one generation a year. Although these solitary bees individually produce small nests, sometimes many will nest in close proximity to each other.

Solitary bee entering ground. Photo by Beth Bolles

Solitary bees are not aggressive and stings are quite mild. Most solitary bees can be closely observed and will elicit no defensive behaviors. Perhaps the most common stings that occur are when the sweat bee, which is attracted to moisture, stings when swatted. Males of some solitary bees, which can not sting, will sometimes make aggressive-looking bluffing flights when defending a territory.

Like the most famous honey bee, solitary bees play a beneficial role in the pollination of plants. Their activity in the spring is short-lived and no management is necessary.

by Larry Williams | Mar 11, 2016

Topdressing material should be weed and nematode-free. Photo Credit: Bryan Unruh, UF/IFAS Turfgrass Specialist.

Q. I see some folks putting a layer of lawn dressing (usually sand) on their lawns in the spring. What’s the purpose for this and is it a good practice?

A. Routinely applying a layer of soil or sand to a lawn can cause more damage than good. This practice is sometimes referred to as topdressing. You can introduce weed seeds, nematodes and even diseases with some sources of lawn dressing. Basically, the only reasons to apply a layer of soil or sand to a lawn are to fill in low areas or bare areas, as a method of dealing with an identified thatch problem or possibly to cover surface tree roots.

Topdressing your lawn with sand on a regular basis is not a recommended practice.

Topdressing soil should be free of weeds and nematodes (sterilized is ideal) and should be of the same soil type (texture) as that on which the turf is currently growing.

While minor low spots can be corrected this way, you can easily overdo it and smother your lawn. Using topsoil from an unknown source may introduce undesirable plants and weeds into the landscape, creating additional work and expense to correct the problem.

It can be difficult to evenly spread the sand in a timely manner. Homeowners start with the best intentions of spreading the sand consistently and finishing by the end of the day only to find that the job is slow and difficult. The sand pile remains in the same spot for days, or longer, shading out and frequently killing the grass below. Once the initial enthusiasm wanes, just trying to reduce the mountain of sand overcomes the objective of spreading it consistently and evenly over the lawn. The end result is dozens of small mounds of sand all over the lawn.

To fill a low spot, shovel the sand, no more than about an inch or two deep, into the area. It’s best to maintain the lawn normally until the grass has grown on top of the first layer. Repeat until the low spot is filled.

Homeowners are sometimes convinced that topdressing will improve the condition of their lawn by increasing the spread and thickness of their turf.

“Topdressing home lawns has minimal agronomic benefits” according to Dr. Bryan Unruh, University of Florida Extension Turfgrass Specialist. When asked his advice for homeowners on topdressing, his reply was “don’t”.

by Julie McConnell | Mar 2, 2016

Those familiar with the Florida-Friendly Landscaping™ Principles know that the number one rule is Right Plant, Right Place. But proper timing is important and should not be discounted! Experienced gardeners recognize that certain flowering and annual vegetable plants have distinctive seasons, but may not realize that turfgrass is seasonal, too.

Warm season and cool season turfgrasses fall into the classes of either annuals and perennials. In North Florida, the most commonly grown turfgrasses are warm season perennials such as Zoysiagrass, Bermudagrass, Centipedegrass, and St. Augustinegrass. These grasses thrive in warm weather and, although they may slow down or even turn brown in the winter, are still very much alive and resume growth readily in the spring. Because they are warm weather lovers, plan to seed one of these species when soil temperatures are warm enough for successful seed germination and when young new grass has enough time to become established without danger of frost damage.

Annual ryegrass label says to plant early spring – but that is too late in North Florida. Photo: Julie McConnell, UF/IFAS

On the flip side there are cool season grasses such as fescue, ryegrass, and bluegrass. These grasses prefer cool weather and do poorly and may go dormant or die when subjected to hot weather. These grasses may be perennials in other areas of the country, but should be treated as cool season annuals if grown in Florida. Cool season grasses may be used as a groundcover in bare spots or to overseed warm season grass from fall through early spring.

When purchasing turfgrass seed, be sure to check with your local extension office to verify that the timing is right for that particular grass. Seed products sold locally may have recommendations that are more relevant to northern climates and performance will differ.

For more information about seeding lawns please read Establishing Your Florida Lawn

by Matthew Orwat | Feb 9, 2016

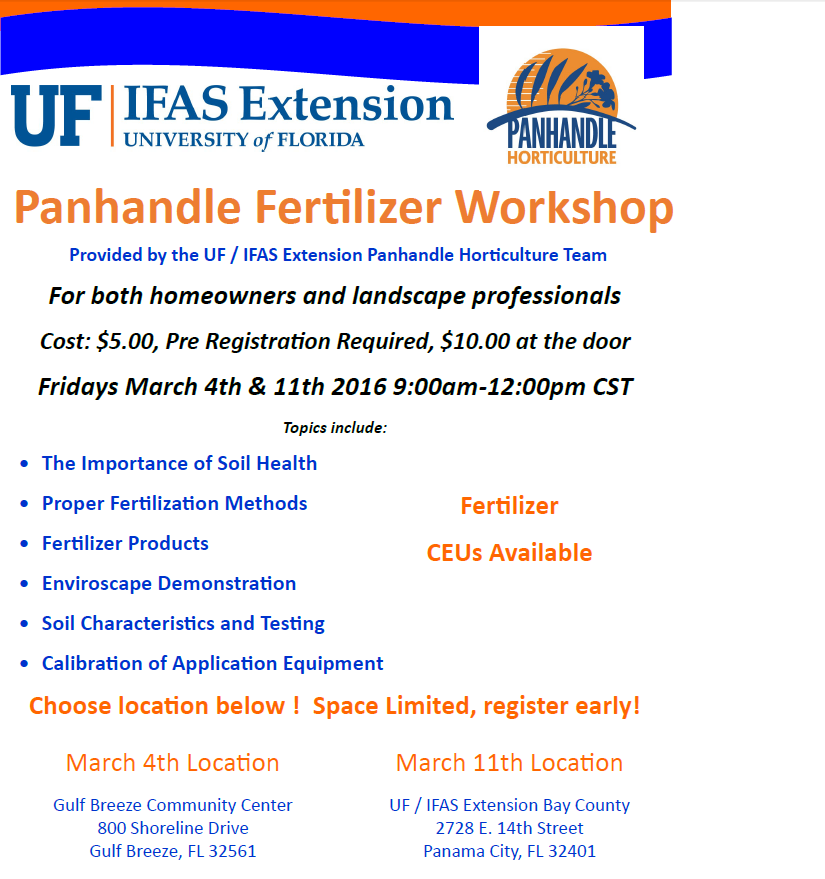

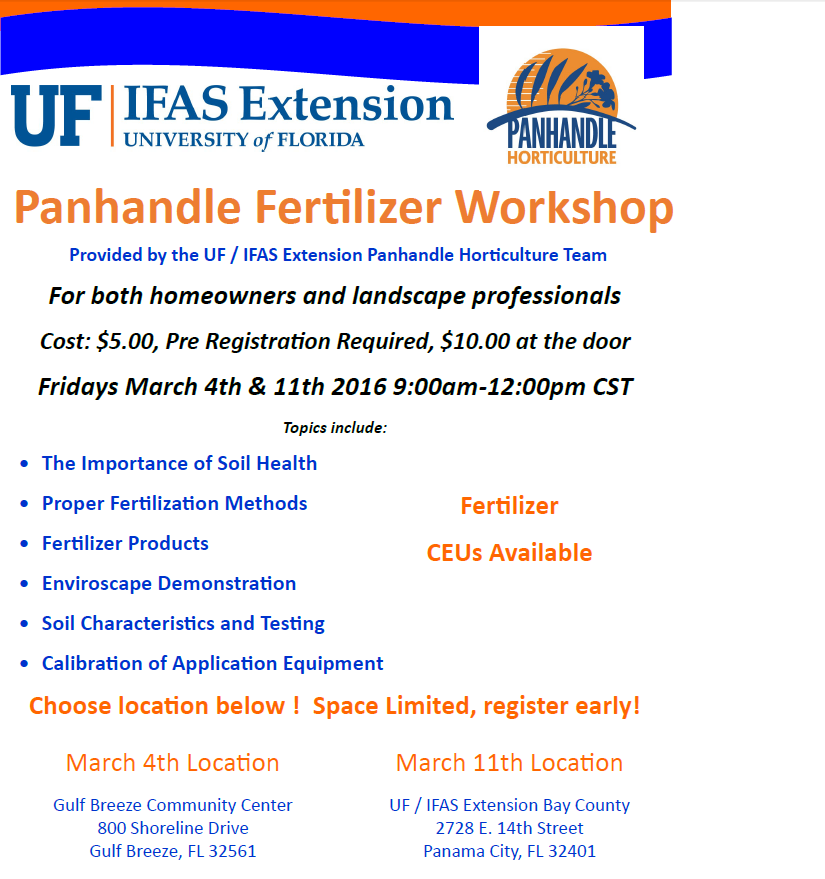

AGENDA

9:00-9:25 Opening Session: Introduction to lawn fertilization, when to fertilize and why proper timing is important, the importance of having a soil test

9:35-11:35 Four concurrent 25-minute sessions:

-

Soil profile example, soil texture example, soil test kits, soil test interpretation

-

Fertilizer spreader calibration

-

Fertilizer products for use on turf & landscapes

-

Enviroscape demonstration – Experience how fertilizers and other potential pollutants can contaminate our waterways

11:45-12:00 Closing Session – The importance of best management practices in fertilizer use

3 CEUs Available total : Urban Fertilizer (2), 482 Core (1) & Demonstration & Research (1)