by Taylor Vandiver | Feb 25, 2014

Considering it is the month of Valentine’s, roses are an appropriate subject to discuss. Not bouquets couriered to various locations all over town, but bushes in the landscape that have been strategically neglected over the winter. Now their time has come; pull on the gloves and get to work.

February is the perfect time to prune rose bushes. Pruning is a step that is required to maintain healthy roses. When roses are pruned, new growth is promoted by removing dead, broken or diseased canes. Pruning also allows the gardener to give their plant an attractive shape and encourage flowering, which is ultimately the reason roses are planted!

Belinda’s Dream rose before pruning. Image Credit Matthew Orwat

Deciding which roses to prune will depend on their class. Hybrid tea, grandiflora and floribunda roses are repeat bloomers and need a moderate to heavy annual pruning this time of year. Some old-fashioned roses and climbers that bloom only once a year should be treated differently and pruned immediately after flowering. They set their buds on old wood from the previous year’s growth; therefore, pruning them would remove most of this year’s blooms. An exception to this would be dead, diseased or damaged wood on any rose bush or canes that are crossing and rubbing. This should be removed immediately upon notice.

There are certain techniques that should be used when pruning any type of rose, no matter the time of year. Any pruning shear, saw or lopper you use should be sharp and sterile. Always wear protective gloves when dealing with roses, unless you don’t mind coming back bloody and mangled.

[warning]

Crown gall and canker can be spread between gardens and individual plants by dirty shears. To prevent the spread of disease, always disinfect pruning shears when beginning to prune with a 5-10% bleach or 20% rubbing alcohol solution, especiallly if they have been used in any other garden. If crown gall or canker has been found in one’s own garden, shears should be disinfected between each plant, no exception. This should also occur when bringing new plants into the garden, until they have been observed to be disease free.

[/warning]

The first step when pruning any rose is to remove dead, damaged or weak stems leaving only the most vigorous, healthy canes. Try to cut the stems one inch below darkened areas, making sure to cut back to green wood. Always make your cut at a 45-degree angle; this will keep water from sitting on top of a stem and causing rot. When pruning try to open up the center of the rose bush. Pruning like this will increase air circulation and help prevent diseases.

Pruning Cut on Belinda’s Dream rose. Image Credit Matthew Orwat

Since roses send out new growth from the bud just below a pruning cut, try to make pruning cuts above a leaf bud facing out from the center of the plant. Make your cut about ¼ inch above the bud and at the same angle as the bud. If any rubbing or crossing branches are noticed, the weakest of those branches should be removed.

Deadheading, or removing spent flowers, can also be done at this time of year. When deadheading, remove the flower by making a cut just above the next five or seven-leaf branch down on the stem. This will allow for a strong and healthy cane to grow in its place. If no live buds remain, remove the entire cane.

Modern reblooming roses (hybrid teas, floribundas, and grandifloras) should be pruned just as the buds begin to swell, which is around mid to late February. When practicing hard pruning, try to leave about four to eight large, healthy canes the diameter of your finger or larger on the shrub. For a more moderate approach, prune shrubs as discussed earlier and cut them back to about 12 to 24 inches from ground level. Generally, any cane thinner than a pencil should be removed.

Belinda’s Dream rose after pruning. Image Credit Matthew Orwat

Don’t worry about pruning recently purchased new roses. Newly purchased roses have most likely been pruned, and no further cutting is necessary. Hopefully with the help of this article you can make a date to spend some quality time with your roses this season. The price of neglect is overgrown roses that are not nearly as attractive.

First flush of properly pruned Belinda’s Dream shrub rose. Image credit Matthew Orwat

Article written by Taylor Vandiver with additional content about sanitation by Matthew Orwat

by Taylor Vandiver | Feb 25, 2014

So you have alkaline soil… What next?

Throughout the Panhandle, a common problem that often arises is finding a way to raise soil pH. This is due to the fact that we often encounter sandy, acid soils in this region. An often overlooked issue is explaining the process of gardening in a soil that tends to be more alkaline in nature.

Soil pH is measured using a scale from 0 to 14. On this scale, a value of 7 is neutral, pH values less than 7 are acidic, and pH values greater than 7 are alkaline. Soil pH directly affects the growth and quality of many landscape plants. Extreme pH levels can prevent certain nutrients from being available to plants. Therefore, a high pH may make it difficult to grow certain plants.

Often alkaline soils occur in the home landscape as a result of calcium carbonate-rich building materials (i.e., concrete, stucco, etc.) that may have been left in the soil following construction. Soils that contain limestone, marl or seashells are also usually alkaline in nature. There are a few measures that can be taken in order to combat high pH. Incorporating soil amendments containing organic material is the most common method implemented to reverse alkalinity. Peat or sphagnum peat moss is generally acidic and will lower pH better than other organic materials. Adding elemental sulfur is another common practice. A soil test will need to be performed often in order to add the correct amount of sulfur to reach an optimal pH level.

Lowering the pH of strongly alkaline soils is much more difficult than raising it. Unfortunately, there is no way to permanently lower the pH of soils severely impacted by alkaline construction materials. In these circumstances, it may be best to select plants that are tolerant of high pH conditions to avoid chronic plant nutrition problems.

Some plants that will tolerate alkaline soils:

-

Shrubs

- Glossy Abelia (Abelia Xgrandiflora)

- Sweet Shrub (Calycanthus floridus)

- Flowering Quince (Chaenomeles speciosa)

- Burford Holly (Ilex cornuta ‘Burfordii’)

- Indian Hawthorne (Rhaphiolepis indica)

Firebush is wonderful butterfly attractant. Photo courtesy of UF/IFAS.

-

Perennials

- Larkspur (Delphinium carolinianum)

- Pinks (Dianthus spp.)

- Firebush (Hamelia patens)

- Plumbago (Plumbago ariculata)

Zinnias come in a variety of colors, shapes and sizes. Photo courtesy of UF/IFAS.

-

Annuals

- California Poppy (Eschscholzia californica)

- Zinnias (Zinnia spp.)

- Cosmos (Cosmos bipinnatus)

by Julie McConnell | Feb 18, 2014

Lichen on trunk of oak tree. Image: Julie McConnell, UF/IFAS

Spanish moss and lichen have earned an inaccurate reputation for damaging trees and shrubs in the Florida landscape. Although they may be found in plants that are in decline or showing stress symptoms, they are simply taking advantage of space available to survive. Both plants are epiphytes and are obtaining moisture and nutrients from the atmosphere rather than from the plants they rest upon.

Spanish moss. Image: Julie McConnell, UF/IFAS

Lichen are more commonly found on plants that are in poor health because they need a plant that is growing slowly and access to sunlight. These conditions can typically be found in thin canopies of trees and shrubs under stress. Although they are firmly attached to the surface of the plant, they are not taking nutrients from the tree or shrub, but rather from the air and other sources such as organic debris and bird excrement. If you find lichen on your landscape plants, look further into what stress factors might be causing the plant to grow slowly such as compacted soil, extreme weather conditions, drought stress, disease or insect pressure.

Spanish moss does not harm trees and many people find it an appealing asset to their landscapes. Common misconceptions about Spanish moss include that the weight causes branches to break and that it is a host site for chiggers. Spanish moss is very light and any additional weight is typically insignificant. Although it may harbor some insects and provide nesting material for birds and other wildlife, Spanish moss in trees is not a site conducive to chiggers because they favor low-lying moist environments.

To read more about Spanish moss, lichens, and other common epiphytes please read the EDIS publication “Spanish Moss, Ball Moss, and Lichens – Harmless Epiphytes.”

by Gary Knox | Feb 11, 2014

This is the time of year when we often see crapemyrtles unnecessarily topped: main stems that are several years old are cut back, often leaving branch stubs 2 – 5 inches or more in diameter. Topping is sometimes called heading, stubbing, rounding and dehorning.

Figure 1. Topping is the drastic removal of large-diameter wood (typically several years old) with the end result of shortening all stems and branches. Topping crapemyrtle is often referred to as “crape murder” because topping usually is not recommended for crapemyrtle. Image Credit Dr. Gary Knox

Figure 2. Topping is the drastic removal of large-diameter wood (typically several years old) with the end result of shortening all stems and branches. Topping crapemyrtle is often referred to as “crape murder” because topping usually is not recommended for crapemyrtle. Image Credit Dr. Gary Knox

In the case of crapemyrtles, another name for this practice is “crape murder”. Topping a crapemyrtle is almost always unnecessary. Because people have seen this done in previous years, home owners often mimic this practice in their own yards, not realizing the unfortunate consequences.

Research at the University of Florida, detailed in this linked publication, found that topping crapemyrtle (“crape murder”) delays flowering up to one month. In other words, unpruned trees may begin flowering in June whereas topped trees don’t flower until July. This research also found topping reduced the number of flowers and shortened the flowering season. Finally, topping stimulated more summer sprouting from roots and stems. Sprouting results in greater maintenance since sprouts are usually removed to maintain an attractive plant appearance.

Unfortunately, landscape professionals and home owners often must maintain crapemyrtles that others planted, and so must deal with the consequences of poor cultivar selection and/or placement. If a crapemyrtle requires routine pruning to fit into its surroundings, it should be replaced with a smaller maturing cultivar. Dwarf crapemyrtles mature at a height of 5 feet; medium crapemyrtle cultivars grow up to about 15 feet in height, and tall or tree-size crapemyrtle cultivars exceed 15 feet and often grow to 20 – 30 feet tall in 10 years.

Best locations for crapemyrtle are areas in full sun with plenty of room for the cultivar size and away from walkways and roads. Proper selection of crapemyrtle cultivar and proper placement in the landscape can result in a low maintenance crapemyrtle without the need for significant pruning.

Figure 3. With proper cultivar selection and placement in the landscape, crapemyrtle develops into a beautifully shaped tree that rarely needs pruning. This crapemyrtle is ‘Muskogee’. Image Credit Gary Knox

For more information, see ENH1138, Crapemyrtle Pruning.

by Alex Bolques | Feb 4, 2014

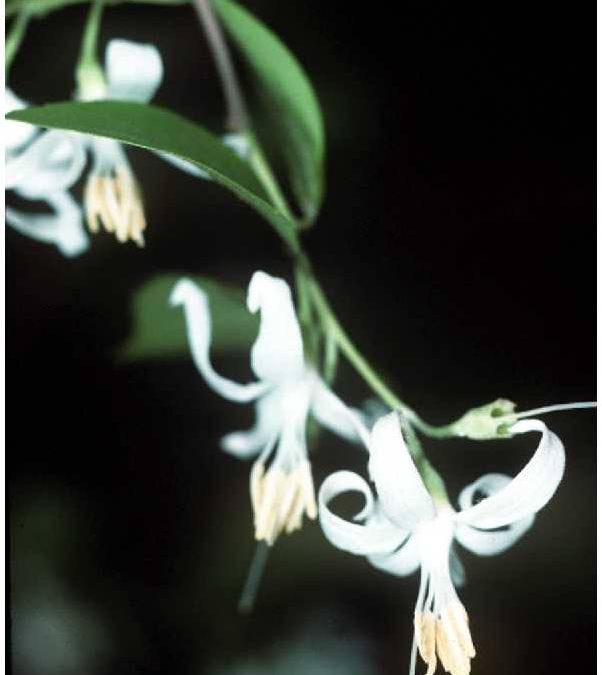

Robert H. Mohlenbrock @ USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / USDA SCS. 1991. Southern wetland flora: Field office guide to plant species. South National Technical Center, Fort Worth.

Found throughout the North Florida Panhandle, the American snowbell, Styrax americanus, is a native small flowering tree. In his book, The Trees of Florida, Gil Nelson describes the blossoms as charming with “the thin, reflexed (flower) petals curve back over the flower base, leaving an attractive mass of yellowish stamens protruding from the star-shaped corolla”. It has dark green deciduous foliage, with the tree reaching up to 16 feet in height. The attractive blooms appear April – July.

Considered as an understory tree, American snowbell grows best in wet partially shaded areas and is somewhat tolerant of full sun. It prefers wet places such as swamps, wet woods, edges of cypress ponds and moist to wet, cool, acid sandy to sandy loam soils. Wet areas of the home landscape where water puddles occur provide adequate growing conditions for the American snowbell.

Wildlife benefits include nectar for bees and butterflies and edible fruit for birds. To try American snowbell in the landscape, check with local native plant nursery or search online. Note: other Styrax species can be found online that are non-native.

Other source: The Native Plant Database

by Matthew Orwat | Jan 27, 2014

Recently, I was working on a camellia identification project in a forgotten camellia garden of about 60 plants. Most camellias I observed were not yet in flower but one in particular caught my eye. I later identified this eye catcher as Camellia japonica ‘Magnoliaeflora’.

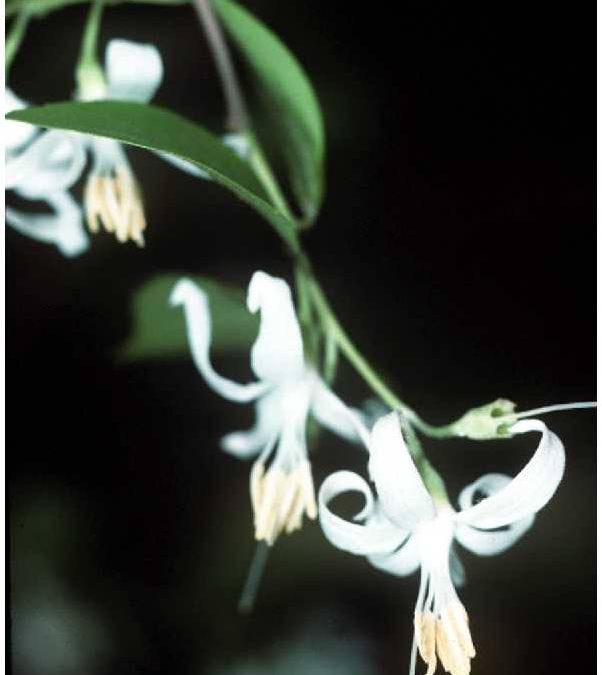

Flower of Camellia japonica ‘Magnoliaeflora’

Image Credit Matthew Orwat

Magnoliaeflora is so named due to its off white magnolia formed semi-double flowers. It’s petals have a distinctive curl and can sometimes resemble a star. Plants are slow-growing but can reach six feet tall and four feet wide after several decades. This slow growth makes it ideal for smaller landscapes where some giant japonica cultivars would be out-of-place.

Its buds and flowers are resistant to cold temperatures, thus flowering is able to occur in mid January, a tad earlier than many other japonicas. This classic camellia should be tried in more Northwest Florida landscapes, particularly newer ones where camellias seem all but absent.

Flower of Camellia japonica ‘Magnoliaeflora’

Image Credit Matthew Orwat