by Mary Salinas | Mar 9, 2017

Dark red flowers of Florida red anise arrive in the springtime. Photo credit: Mary Derrick, UF/IFAS Extension.

Springtime brings small but very pretty red blooms on an outstanding native shrub/small tree, Florida red anise (Illicium floridanum). It occurs naturally in the wild in the central and western panhandle of Florida and west along the gulf coast into Louisiana. Its natural environment is in the understory along streams and in rich, wooded areas.

This is a great shrub for a part shade to shady and moist area in your landscape. The dense foliage, dark green leaves and the fact that it is evergreen all year makes it a great choice for an informal hedge. Plan for it to grow to a maximum height of 12 to 15 feet.

Dense growth habit of Florida red anise. Photo credit: Mary Derrick, UF/IFAS Extension.

The leaves have a licorice-like aroma when crushed but this is NOT the species that gives us the edible culinary anise. Maybe it is that aroma that makes this a relatively pest-free plant!

Yellow anise (Illicium parviflorum) is a very similar native shrub but has small yellow flowers and adapts better to a drier environment. The native range of the yellow anise is north central Florida.

by Julie McConnell | Jan 17, 2017

Winter flowers and small leaves with serrated edges lead to identification as Camellia sasanqua. Photo: J_McConnell, UF/IFAS

A common diagnostic service offered at your local UF/IFAS Extension office is plant identification. Whether you need a persistent weed identified so you can implement a management program or you need to identify an ornamental plant and get care recommendations, we can help!

In the past, we were reliant on people to bring a sample to the office or schedule a site visit, neither of which is very practical in today’s busy world. With the recent widespread availability of digital photography, even the least technology savvy person can usually email photos themselves or they have a friend or family member who can assist.

If you need to send pictures to a volunteer or extension agent it’s important that you are able to capture the features that are key to proper identification. Here are some guidelines you can use to ensure you gather the information we need to help you.

Entire plant – seeing the size, shape, and growth habit (upright, trailing, vining, etc.) is a great place to begin. This will help us eliminate whole categories of plants and know where to start.

Stems/trunks – to many observers stems all look the same, but to someone familiar with plant anatomy telltale features such as raised lenticels, thorns, wings, or exfoliating bark can be very useful. Even if it doesn’t look unique to you, please be sure to send a picture of stems and the trunk.

Leaves – leaf color, size and shape is important, but also how the leaves are attached to the stem is a critical identification feature. There are many plants that have ½ inch long dark green leaves, but the way they are arranged, leaf margin (edges), and vein patterns are all used to confirm identification. Take several leaf photos including at least one with some type of item for scale such as a small ruler or a common object like a coin or ballpoint pen; this helps us determine size. Take a picture that shows how leaves are attached to stems – being able to see if leaves are in pairs, staggered, or whorled around a stem is also important. Flip the leaf over and take a picture of the underside, some plants have distinctive veins or hairs on the bottom surface that may not be visible in a picture taken from above.

Flowers – if flowers are present, include overall picture so the viewer can see where it is located within the plant canopy along with a picture close enough to show structure.

Fruit – fruit are also good identification pictures and these should accompany something for scale to help estimate size.

Any additional information you are able to provide can help – if the plant is not flowering but you remember that it has white, fragrant flowers in June, make sure to include that in your description.

Learning what plants you have in your landscape will help you use your time and resources more efficiently in caring for you yard. Contact your local UF/IFAS Extension office to find out who to send requests for plant id.

by Beth Bolles | Dec 22, 2016

A new tree or shrub is an investment for the future. When we pick an ornamental plant, we have the hope that it will survive for many years and offer seasons of beauty that enhance our landscape. Time is often spent picking a suitable spot, preparing the planting hole, and watering until establishment. We give it the best of care to make certain that our new plant becomes a more or less permanent feature.

With all of our tender love and care for new ornamentals, there is one important practice that we may neglect. Most homeowners purchase plants in containers and it is common to find root balls with circling roots. If any root ball problems are not addressed before installation, the life of your plant may be shorter than you want.

Ten years after installation, this plant was ultimately killed by girdling, circling roots. Photo by Warren Tate, Escambia County Master Gardener.

The best practice for woody ornamentals is to cut any roots that are circling the trunk or container. Homeowners may slice downward through the root ball around the entire plant. For shrubs, it is recommended to shave off “the entire outside periphery of the rootball” to eliminate circling roots. These practices allow the root system to grow outward into new soil and greatly reduce the possibility of girdling roots killing your plants years after establishment.

Circling roots are cut before installation. Photo by Beth Bolles, Escambia County Extension.

For more information on shrub establishment, visit the UF Publication Planting Shrubs in the Florida Landscape.

by Julie McConnell | Nov 22, 2016

Missing rose buds, pulled up pansies, and damaged tree trunks are all signs that something has been visiting your garden while you are away. But what could it be? Most gardeners are familiar with leaf spots caused by fungal diseases or minor feeding damage by insects, but to see half a shrub or an entire flower bed demolished overnight indicates a different type of pest.

Missing rose buds, pulled up pansies, and damaged tree trunks are all signs that something has been visiting your garden while you are away. But what could it be? Most gardeners are familiar with leaf spots caused by fungal diseases or minor feeding damage by insects, but to see half a shrub or an entire flower bed demolished overnight indicates a different type of pest.

There are several mammals that visit home landscapes and may cause damage, especially in times of drought when natural food sources are limited. Because we provide water for our landscapes, our plants tend to have lush new growth at times when plants in natural areas have slowed growth because of a lack of water or other stressors that managed gardens do not face. So, it’s no surprise that herbivores will be attracted to our landscape for a midnight snack.

It is important to determine what is causing damage so that you can employ protective tactics if possible. Some things to look for to try to figure out who the culprit is are footprints, dropping, feeding clues (bite marks, scrapes, etc.), or other distinctive damage. For more details about how to tell the difference between damage caused by multiple pests see How To Identify the Wildlife Species Responsible for Damage in Your Yard.

Once you have determined what is causing the damage you can try some different strategies to deter future feeding. Some plants may be impossible to protect, but before you spend your money and time check out these recommendations by wildlife specialists at the University of Florida in How to Use Deterrents to Stop Damage Caused by Nuisance Wildlife in Your Yard

by Mark Tancig | Nov 16, 2016

Female saltbush plant in bloom. Credit: Niels Proctor, hort.ifas.ufl.edu

If you have noticed bursts of white-flowered shrubs along roadsides, trails, and other natural areas the last couple of weeks, there’s a good chance that it was saltbush (Baccharis halimifolia). Saltbush is a native shrub in the sunflower or daisy family (Asteraceae) that can be found throughout the Coastal Plain. It often grows along the edges of freshwater and brackish water wetlands, but also seems happy in upland sites as well. It prefers sunny sites and can reach a height of ten to fifteen feet. There are separate female and male plants of this species, with females having the showy, white blooms while males are somewhat plain.

While it can be quite common in natural areas, it is rarely seen in the home landscape. Although saltbush is a somewhat leggy shrub, its home landscape value comes from the fact that it blooms at a time when most other plants are done blooming or are going into dormancy. In addition to its show of white flowers at a time when many other landscape plants are becoming drab, saltbush is also an important nectar source for migrating monarch butterflies. It is also tolerant of salt spray, so makes a good addition to the landscape in coastal areas.

Leaves and seed of saltbush. Credit: Niels Proctor, hort.ifas.ufl.edu

Saltbush may be hard to find in the retail nursery trade, but can often be sourced from nurseries that specialize in native plants or ecosystem restoration plantings. There are male and female plants, so when purchasing, you may want to see it in bloom to verify that you picked a female. If you know someone with saltbush on their property, you can start some on your own by collecting seed or propagating it through soft or hardwood cuttings.

If you would like to try out an underused, native shrub that provides great late fall color and helps feed monarch butterflies for their journey home, plant a saltbush in your landscape. You may have neighbors asking about that unusual, but pretty, shrub.

More information can be found at Baccharis halimifolia Salt Bush, Groundsel Bush

by Blake Thaxton | Nov 3, 2016

It was a hot summer that has continued into Fall. We hope cooler temperatures are on their way to the panhandle of Florida. Fall can be a great time to spruce up your landscape with some new shrubs.

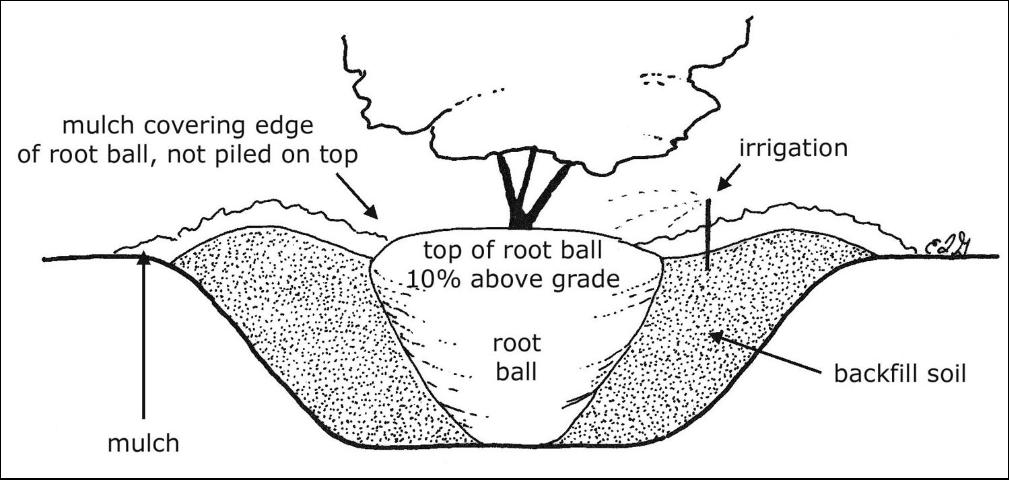

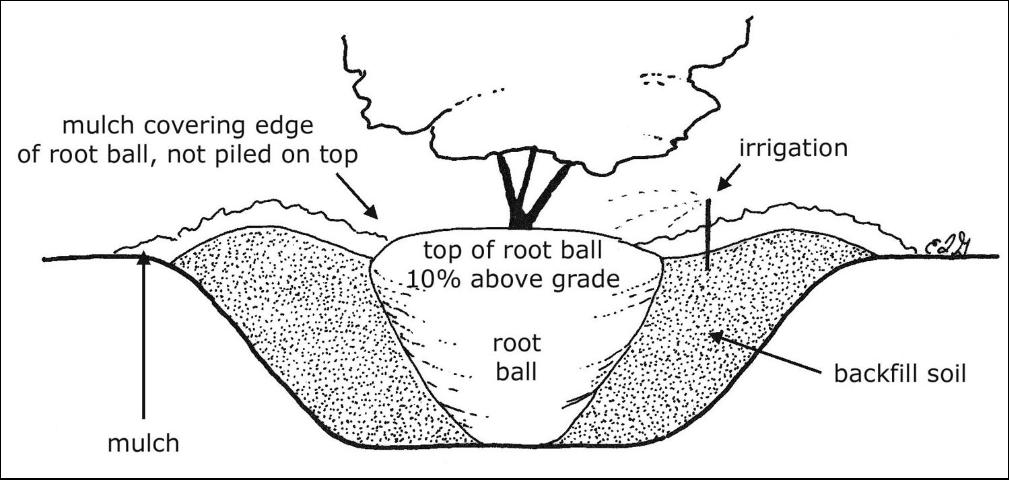

Image Credit UF / IFAS

It may be time for your landscape to receive a mini-makeover and to get a new look. Perhaps some strategically placed shrubs will be what makes an outdoor living space pop. Proper selection and installation is key to future health of new shrubs.

Selection

There are several factors that need to be considered before installing new shrubs to the landscape. Selecting plants carefully, based on the following points, will help with long-term success of the plant:

- Climate – Be sure that the species are climate appropriate.

- Environment – Study the light level, acidity, and drainage of the planting site.

- Space – Account for the mature size of the plant before planting. This will eliminate the possible need for plant removal if space is not adequate.

- Inspect the plant – Check for mechanical injury (scars and open wounds), cold injury, condition and shape of the canopy, and examine the root system.

Installation

Now that essential considerations have been made, it is time to give the shrub the best chance for survival with proper installation techniques. Fall and winter is an ideal time for planting shrubs. The roots can develop before the tops begin to grow in spring. The following are keys to proper establishment of container shrubs.

- Root ball preparation – Remove the container from the root ball and inspect for circling roots. If there are circling roots than make three or four cuts vertically to cut the roots. Pull some of the roots away so they will take on a new growth direction (massage the roots). Also find the top most roots, as sometimes they are covered by extra potting media. Remove the extra potting media so the top most roots are exposed and become the top of the root ball.

Image Credits: UF/IFAS, Edward F. Gilman

- Wider is better – Dig the hole two or three times the diameter of the root ball.

- Proper depth – Make sure to dig the hole 10% less than the height of the root ball. In poorly drained soils dig the hole 25% less than the height of the root ball. The top most roots should be slightly above the native soils.

- Backfill – Fill the hole with existing soil half way and tamp the soil to settle. Again fill the rest of the hole with the existing soil and tamp again to settle the soil. Do not place any backfill soil or mulch over the root ball as it is crucial that water and air are able to be in contact with the roots.

- Aftercare – Irrigate daily for the first two weeks, followed by every other day for the next two months, and weekly until the shrub is established (For <2 inch caliper shrubs).

If these key points are followed regarding selection and installation, the shrubs will be well on their way to becoming established in the landscape. If you would like read more in detail about installation please read the following:

Specifications for Planting Trees and Shrubs in the Southeastern U.S.

Literature:

Gilman, E.F., (2011, August) Specifications for Planting Trees and Shrubs in the Southeastern U.S.. Retrieved from: http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/ep112

Black, R.J. and Ruppert, K.C., (1998) Your Florida Landscape, A complete guide to planting & maintenance. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida.