by Joshua Criss | Oct 10, 2025

Planning landscaping is undoubtedly not easy. The primary concern relegated to each individual homeowner is what you want out of your yard. Many are content with just grass, while others desire a diverse array of plant life. One aspect oft overlooked is your landscape’s capacity to be a boon for local wildlife. With a bit of planning, your property could be literally buzzing with insect pollinators, wild birds, and even our reptilian friends.

Where to Start

For this article, let’s begin with a newly established development. What has happened in this scenario from an ecological perspective, with what we’d call primary succession? In short, this means an area that experienced a complete reset of its plant communities. In nature, this would be the result of events such as a volcanic eruption, but in Florida, it’s far more likely due to bulldozers.

Now, the good news in this scenario is that you won’t be receiving your property in this condition. The developer has fast-tracked the process by planting grasses and some basic trees by the time you’ve purchased the property. It’s from this basic setup that you, my new homeowning friends, can begin your husbandry of our local animals.

Begin by investigating the where your new home was built. If it began as a wetland, you’ll want to select plants appropriate for that environment. The same is true if you’ve moved into what was forest land. This thought aligns directly with the first of our FL Friendly Landscaping principles: right plant, right place. There is little sense in putting plants that don’t like wet feet into a poorly draining soils common in wetlands.

UF/IFAS Photo: J. Criss

Consider Your Environment

You’ll also want to investigate the wildlife that is endemic to those environments and areas. Knowing what is there, and what you’d like to attract to your landscape, will help you decide which plants will be best. For instance, replacing a crape myrtle (Lagerstroemia indica) with a red maple (Acer rubrum) in what was previously a wetland environment puts a tree better suited to that environment, which will require less maintenance from the homeowner. Additionally, red maples are known to be an early-season nectar source for a multitude of moths and butterflies while providing nesting sites for local birds.

Red maples are a great example of plant selection and what it can do to attract wildlife to your yard, but there are other guidelines with which you’ll want to be familiar should this be your goal.

Guidelines for Attracting Wildlife

Water is critical to all life on the planet, including wildlife. Providing water features in your garden will increase the chance for animals visits to your garden. This can be as basic or as elaborate as you’d like. Everything from a pond to a simple dish of water will suffice. One common water feature challenge to consider for Florida gardeners are mosquitos. Avoiding these pesky creatures could be as easy as creating flowing water features. Solar fountains are an easy and cheap way to accomplish that goal.

Shelter is another critical aspect to attract wildlife. Either natural or man-made, it is essential to attracting and keeping various species in your yard. Bird, bat, or owl houses are perfect solutions to this issue. Just ensure you site them correctly to provide the correct environment for the animal in question.

Design your landscape to be layered. In this instance, this means integrating shrubs, trees, herbaceous plants, and groundcover. Doing so will provide some cover for feeding while providing visual interest to your home.

Last and certainly not least, choose plants known to be a food source. When doing so, you’ll want to research how those animals you’d like to attract eat. For instance, hummingbirds (Trochilidae) have a small, curved beak. If this is the species you’d like, you’ll want to select plants rich in nectar with tubular flowers. Firebush (Hamelia patens) is an excellent example of a plant for this purpose.

UF/IFAS Photo

Conclusion

Bringing local wildlife into your yard is an excellent way to get to know the small creatures living in your area. A few simple changes may go a long way toward reintroducing habitat to an area where it may be waning. For more information on attracting wildlife or any horticulture topic, refer to your local Extension office

by Danielle S. Williams | Oct 3, 2025

Peanuts, also known as groundnuts, earthnuts or goobers have a long history of cultivation. Unlike tree nuts, peanuts are grown underground which is how they earned the nicknames groundnut or earthnut. Originally native to South America, peanuts made their way to North America from Africa, where they were introduced by African slaves in the early 1800’s.

Overturned peanuts in a field ready to be harvested. UF/IFAS Photo by Tyler Jones

First grown in Virginia, peanuts were grown mainly for oil, food, and as a cocoa substitute. During this time, they were regarded as food for livestock and the poor. It wasn’t until the late 1800’s did their demand increase as there was a need for an affordable, high-protein food during the Civil War and World Wars. Their popularity also increased when showman, P.T. Barnum began selling hot roasted peanuts at his traveling circuses.

In the 1900’s, peanuts became a significant agricultural crop when the cotton boll weevil threatened the South’s cotton crop. Through the research findings and suggestions of Dr. George Washington Carver, peanuts were grown as a successful cash crop and contributed greatly to the sustainability of the farm. Though Dr. Carver did not invent peanut butter, he did invent more than 300 new uses for the peanut and peanut byproducts including shaving cream, leather dye, coffee, ink and shoe polish.

Jar of peanut butter surrounded by loose shelled peanuts. UF/IFAS Photo by Tyler Jones

Today, peanuts are grown in 13 states, across the United States and the U.S. is the third largest producer of peanuts in the world. In 2024, Florida harvested 157,000 acres of peanuts, averaging about 3,500 pounds per acre with a production value of roughly $149.5 million (Annual Crop Production 01/10/2025).

Peanut Fun Facts:

- 99% of peanut farms are family-owned, businesses averaging 200 acres

- There are four different types of peanuts – Runner, Valencia, Spanish and Virginia

- Peanut plants are legumes and fix beneficial nitrogen back into the soil

- Peanut butter is an excellent source of niacin, and a good source of vitamin E and magnesium

- Peanuts do not contain cholesterol and are low in saturated fat

- Peanut butter accounts for half of all peanuts eaten in the U.S.

- It takes about 540 peanuts to make a 12-ounce jar of peanut butter

- There are enough peanuts in one acre to make 35,000 peanut butter and jelly sandwiches

- The average person will eat almost 3,000 peanut butter and jelly sandwiches in their lifetime

- Women and children prefer creamy peanut butter, while most men opt for chunky

- Peanut allergies affect about 1.8% of U.S. children and 1.1% of adults the U.S. population

UF/IFAS Peanut Butter Challenge

Help us fight hunger by donating unopened, unexpired jars of peanut butter to the Peanut Butter Challenge! Every year UF/IFAS Extension Offices across the state coordinate the Peanut Butter Challenge to address hunger and food insecurity in our area. You can support the challenge and help fight hunger by donating unopened, unexpired jars of peanut butter, now through October 31st, 2025 to your local UF/IFAS Extension office. Thanks to support from the Florida Peanut Producers Association and the Florida Peanut Federation, your peanut butter donations go even further!

by Lauren Goldsby | Sep 25, 2025

While planning my fall garden I have been partaking in one of my favorite pastimes—shopping for seeds. This is always more fun to me than planting the seeds. Seeds come in many different packages and just like wine, you can be drawn in just from the carefully crafted label. Many of the seed labels I encountered shared the same marketing phrase, “non-GMO seeds”, which is like seeing a gluten free label on your pineapple. It was never an option!

Genetically engineered plants take decade(s) to produce, test and release. They are expensive and are not typically sold in small quantities. These patented seeds will not be sold to you by accident. GMO crops that are grown and sold in the US on a commercial scale include alfalfa, apple (Arctic), canola, corn, cotton, eggplant, papaya, pineapple (pink), potato, soybean, squash, sugarbeet, and sugarcane. More information about each crop here: https://www.ams.usda.gov/rules-regulations/be/bioengineered-foods-list

Recently, a few GE seeds have been developed for the home gardener.

The Firefly Petunia glows in the dark thanks to the insertion of genes from a bioluminescent mushroom. More info

The Purple Tomato has purple skin and purple flesh thanks to the insertion of snapdragon genes. This is the first genetically engineered food crop developed for the home gardener. More info

These seeds are only available from certain retailers, and you will pay a premium for this technology.

When purchasing seeds consider other factors like season and variety. “Right plant, right place” – you hear us say those four words again and again here at the Extension Office. That’s because plant selection is one of the most important things to consider for gardening success. If you were to start a watermelon from seed right now it may do well at first. However, they thrive in the heat of the summer, and they will not like the short, cool fall days. A plant growing in the wrong environment will be stressed. That stress attracts pests and can make a plant more susceptible to pathogens.

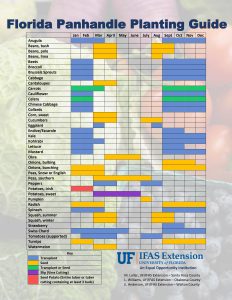

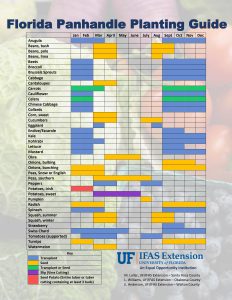

Set yourself up for success by growing plants when they are in season. Don’t be tempted by the seeds you see on the aisle end caps. These are not always specific to each region and just because they are selling it now does not mean it should be grown right now. Decide what you are going to grow before you go to the store! The Florida Panhandle Planting Guide is a great resource to use for planning your garden. If you find that you purchased seeds for the wrong season save them for the next one—and consider that your newest hobby may be seed collecting.

by Ben Hoffner | Sep 11, 2025

Photo credit to Daniel Leonard, Calhoun County Extension Agent

When maintaining proper care of your trees and shrubs in your lawn or landscape it is important to not damage stems and trunks. It is best practices to keep the area around the tree clean, but it needs to be done properly. Mowing and weed eating is not recommended due to the possibly of severe damage to the trunk and stems. Repeated damage from mowers and weed eaters cause damage called girdling. There are a few very effective ways to protect the trunk and stems from damage such as mulching and using tree rings/tubes.

Repeated damage to the base of the tree and stems will affect the cambium layer. The cambium layer is a thin layer of living tissue directly under the bark of the tree, and it supports the growth and well-being of the tree, actively dividing cells located between the xylem (wood) and phloem(bark). Constant damage of this layer will cut off the flow of carbohydrates to the roots, which will cause the tree to die. This layer is the green material you see after the bark of the tree has been damaged. It is imperative to keep the cambium layer damage free to insure the best tree health.

Photo credit to Daniel Leonard, Calhoun County Extension Agent

Taking preventive measures will ensure the prolonged life of your tree. Using mulch around the perimeter of the tree for protection from injury is the most effective method of protection. There are different mulch types like straw, bark, leaves, needles, wood or grass. These are examples of organic mulches. Tree rings and tubes can be helpful to protect young trees. If mulch is not the best option for the plant, other materials such as cut sections of plastic pipe or rubber tires could be an option for protection.

Mulch is not only a great way to protect your trees from injury. It also helps with retaining moisture, erosion control, weed suppression, organic accumulation and aesthetic appeal. Following simple guidelines when using mulch will make sure that you are maximizing the material used. Maintain a 2-to 3-inch layer around your established trees. Avoid “volcano mulching”. “Volcano mulching” is when mulch is piled against the base of the tree, it holds moisture. High amounts of moisture can cause the trunk to rot.

To prolong the life of your trees and shrubs you must protect them from injury that can cause girdling. Avoid constant contact with lawn mowers and weed eaters that will destroy the cambium layer. Using mulch is a very effective way for protection as well as retaining moisture, erosion control, weed suppression, organic accumulation, and aesthetic appeal.

For more information contact your local UF/IFAS Extension Office.

by Mark Tancig | Aug 28, 2025

A healthy coneflower in Leon County’s Demonstration Garden. Credit: Jessica Thrasher

My last Gardening in the Panhandle article was about the many diagnostic services provided by UF/IFAS Extension. In this article, I get to share the results of those services concerning samples recently submitted to the North Florida Education and Research Center (NFREC) Plant Disease Diagnostic Clinic (PDC).

Anthracnose in Dogwood (Cornus florida)

Before you get too concerned, this is not the dogwood anthracnose (Discula destructiva) that many of us have heard about from friends and colleagues up north, but one of the more common anthracnose species (Colletotrichum gleosporoides) that infects a variety of fruits, vegetables, and ornamentals.

Typical leaf symptom of common anthracnose disease on a magnolia. Credit: UF/IFAS.

This sample came from a homeowner who brought us a branch from a sick looking dogwood. As many of you know, due to a host of issues, from a short lifespan to living in the southern end of its range in a warming climate, dogwoods have been faring pretty bad lately, with most landscape plantings showing signs of decline or death. While Florida extension agents are informed that it is not the terrible anthracnose from up north, some couldn’t help but think the worst. I was delighted to get a good sample for identifying the disease – one that showed both healthy tissue and diseased tissue – and finally confirm what is causing the common decline symptoms seen in Leon County dogwoods. We bagged up the sample and delivered the next day to the NFREC PDC.

Within a week, the results came back and confirmed the run-of-the-mill anthracnose. This Anthracnose, caused by the fungus Colletotrichum gleosporoides, causes lesions (spots) and/or blights (larger areas of the leaf browning) beginning at the leaf margins that tend to expand and end up causing premature leaf drop. Unfortunately, once we see the damage, typically in the summer, it is too late for any remedy, as the infection begins in the spring. In addition to good practices to encourage good airflow – proper spacing, pruning – and minimize moisture on leaves – irrigate the soil, not the leaves, water in the morning – you will also need to be able to handle some amount of damage. Removing fallen leaves and branches is also helpful to reduce the chance of it cycling back the following spring. Chemical control options include 2-3 applications of preventative fungicide sprays containing chlorothalonil, myclobutanil, mancozeb, or thiophanate methyl early in the spring according to label directions.

Aster Yellows in Purple Coneflower (Echinacea purpurea)

The deformed blooms of a coneflower with Aster Yellows. Credit: Jessica Thrasher

I’ve had a few questions about Aster Yellows (Candidatus phytoplasma asteris) over the years but have never positively identified the disease in plant material. So, I was somewhat excited to see some of the purple coneflowers in our demonstration garden showing peculiar symptoms. Actually, I was alerted to the strange looking plants by a Master Gardener Volunteer who had been weeding the area. We delivered a sample to the NFREC PDC and in just over a week had results.

Aster Yellows is a disease caused by a phytoplasma and the sample can only be diagnosed with molecular techniques and genetic sequencing. Phytoplasmas, by the way, are a type of bacteria that lack a cell wall and are transmitted plant to plant via insect vectors, typically leafhoppers. Once inside the plant, these phytoplasma can move with plant sap and begin to disrupt the vascular system, causing malformed and discolored flowers, plant deformations, and stunted growth. While members of the Aster family – daisy, sunflower, goldenrod – are common hosts of the disease, Aster Yellows has been found to infect over 300 species in at least 38 plant families. Other species of phytoplasma, also causes lethal yellowing and lethal bronzing of palms and several witch’s-broom diseases.

Since there are not any chemical treatments for Aster Yellows, prevention is key. Once observed, it’s best to remove the infected plants as soon as possible to prevent spreading to other nearby species. In agricultural settings, the leafhopper spreading the bacteria becomes the main target to control using various insecticides. However, in ornamental settings, simply removing the infected plants is the recommended practice.

Stay Observant

Many common diseases are present in every landscape. By ensuring soil and plant health, many of these diseases can be tolerated with little damage. It is important for gardeners and landscapers to be on the lookout for problems so they can be dealt with before they get out of hand. UF/IFAS Extension provides assistance through our county offices and diagnostic clinics to help confirm identification of the pest and provide science-backed control options. If you think you have an issue in your landscape, please reach out to your local county extension office.

Article co-authored by Fanny Iriarte, Diagnostician with NFREC PDC.

by Donna Arnold | Aug 15, 2025

Kalanchoe Species in Florida: Invasive Threats and Management

Several species of Kalanchoe, widely distributed through horticulture as popular containers and landscape plants, have escaped cultivation and become invasive in Florida. Of the approximately seven species reported outside of cultivation, two have been documented as particularly problematic: Kalanchoe pinnata (commonly known as Cathedral Bells) and Kalanchoe × houghtonii (known as Mother of Millions). Both are listed as Category II invasive plants by the Florida Invasive Species Council (FISC), indicating they have the potential to disrupt native ecosystems. “In Central and South Florida, the plant is listed as invasive; hhowever, there is a cautionary note for North Florida.”

Photo Credit: Donna Arnold, FAMU Extension

Kalanchoe × houghtonii is a hybrid of K. delagoensis and K. daigremontiana, which has led to some confusion in reporting and distribution records. These species belong to the Crassulaceae family and are characterized as succulent herbs with hollow, fleshy stems. K. pinnata features rounded, scalloped leaves, while K. × houghtonii has slender, pointed, fleshy leaves. Their bell-shaped, pendulous flowers range in color from green to red. In Florida, these plants are primarily found in South Florida and along the East Coast, extending as far north as Nassau County.

Photo Credit: Donna Arnold, FAMU Extension

The ecological impacts of Kalanchoe species are significant. Reproduction occurs both sexually and vegetatively, with plantlets forming along leaf margins and even on inflorescences. This species high reproductive rate and ability to thrive in dry, arid environments allow them to invade coastal dune habitats, where they form dense carpets that crowd out native species. Shallow root systems contribute to destabilization of sandy areas by displacing native plants such as sea oats, which are essential for anchoring sand and preserving dune integrity.

Effective management begins with prevention. Homeowners are advised not to plant Kalanchoe species and to avoid dumping landscape material in natural or disturbed areas. Physical control methods include hand-pulling and secure disposal of plant material to prevent regrowth. Chemical control can be achieved using a 5% glyphosate foliar spray, which is effective in killing individual leaves that might otherwise produce new plantlets. Follow-up removal of detached leaves is essential to prevent further spread. Currently, there are no known biological control methods for these species.

For more information and personalized management recommendations, homeowners should consult their local UF/IFAS Extension office. Additional resources are available through the UF/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants, and the Florida Invasive Species Council Plant List.