Video: Smilax Vines

Smilax is a common vine that can pop up in unwanted spots in landscapes. Learn about how this plant grows and management techniques with UF IFAS Escambia County Extension.

Smilax is a common vine that can pop up in unwanted spots in landscapes. Learn about how this plant grows and management techniques with UF IFAS Escambia County Extension.

One of the more popular flowering perennials grown in the landscapes of Florida and throughout the Southeast is the daylily. This blooming perennial traveled with many of the early settlers. They brought this plant for several reasons beyond the enjoyment of the bloom display, it was considered a source of food by including the petals and buds into the cooking of specific dishes.

The daylily is an easy to grow plant that requires less management than many of the other perennials grown in the garden settings of the landscape. Daylilies are linked to the lily family but are not actually in this family, Hemerocallis in Greek is Hemero for “day’ with Callis meaning “beauty”. The passion by many professional breeders and novice growers can be seen in the many selections and varieties in the plant industry today. This plant brings interest and joy to anyone that visits your landscape gardens.

This clump forming plant can be grown in different soil types from sandy loam, clay to muck edges near wetlands. The location for best performance is sandy well drained soil with high amounts of organic matter. It has a moderate salt level tolerance lending itself as one perennial to consider in coastal settings. The best way to accomplish the levels of organic matter is to till the bed area for planting, add three to four inches of compost or well-rotted manure plus a ½ pound of 3:2:1 ratio fertilizer to a 100 square foot bed. The 3:2:1 is a Nitrogen, Phosphorus and Potassium fertilizer recommendation. Till all of this into the previously tilled bed to a six-inch depth. This mix of sand or clay with organic matter at the six-inch soil depth places it where the roots will grow.

Daylilies multiply in several different ways from forming clumps of plants from a single plant over three to four years that can be divided into separate plants and replanted to expand the bed area for managing the color display of the original plant. Plant breeders cross pollinate between selected plants that have desirable characteristics. These characteristics may be ruffled outside edges on the petals, bright or daker petal color, a change in color from the outside portion of the flower petal to the throat area at the center of the bloom or even the height of the scape which is the stem that emerges from the leaf clusters near the base that supports the flower display.

Daylilies can be purchased at many box stores in containers and easily transplanted in the garden. Another option is to visit local daylily nurseries as they often have more named variety options with many different flower colors available. Local nurseries usually grow plants in the ground so they will need to be dug and purchased as a bareroot. When planting bareroot daylilies look at the location where the leaves emerge near the base just above root area and plant one and a half to two feet apart. Make sure to plant no deeper than at that point of root and leaf growth area known as the crown. The crown must be above the soil level for quality growth.

After planting and watering in the plants be sure to mulch the bed with three to four inches of pinestraw or bark mulch. This manages weed growth and keeps soil moisture at consistent levels reducing stress to the plant. If periods of dry weather conditions occur watering the plants will be needed to keep the plants from stressing.

How many blissful summer days have been disrupted in Florida by biting or stinging insects? More than a few. Mosquitoes, fire ants, yellow flies, dog flies, no-see-ums, yellowjackets, and more all live in our area and are either gleefully happy to violently defend their territory or actively seeking people out as food. One more creature to add to the list, though it is technically an arachnid rather than an insect, is the chigger.

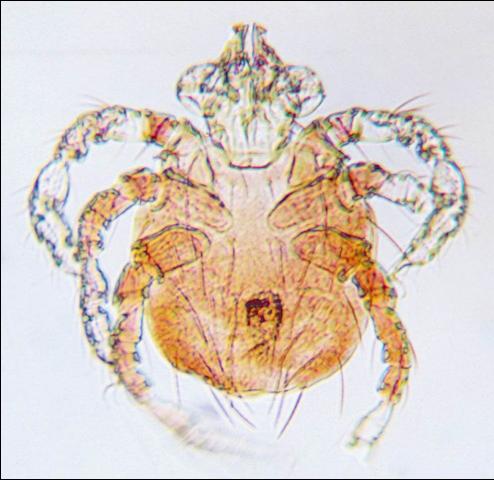

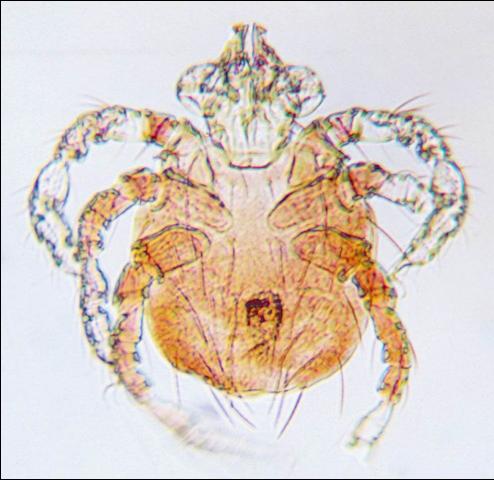

Chiggers, also known colloquially as red bugs, are the larvae of mites in the family Trombiculidae. They are difficult to see, even as adults, because of their diminutive size. They’re tiny. So tiny, in fact, that you may not be able to feel them even if they’re crawling all over you. They don’t seem to have any claustrophobia, rather enjoying the tightest spaces under clothing and spots where skin is thin and tender. This leads to bites in some very uncomfortable places. When they bite, chiggers temporarily attach themselves to their host and inject a digestive fluid into the skin. This triggers an immune response in people; our bodies don’t seem to like being partially digested and sucked up by tiny critters. Even if the body’s response means the mite doesn’t finish its meal, it still leaves a mark. Different people may have varying sensitivity to the bites, but it is never a pleasant experience. Itching sets in four to eight hours after the bites, which may be accompanied by red welts or bumps on the skin. Severe reactions may lead to fever.

Chiggers do not attach themselves permanently to people, nor do they burrow under the skin. If you’re lucky enough to discover any mites still biting you, take a hot shower and lather with soap several times. Nail polish applied to the bites will not help, though strangely enough meat tenderizer may help with the itching. Antiseptic is always a good idea as well, and if you’re short on meat tenderizer, an over-the-counter anti-itch product will serve too.

To avoid running afoul of chiggers, be aware that they are most likely to be found in low, damp areas outdoors with shrubby vegetation. They may be found elsewhere, but one persistent myth is that they like to inhabit Spanish moss. In reality, they don’t have any particular attraction to it.

Thankfully, insect repellants that contain DEET repel chiggers as well as other pests. For maximum effectiveness on chiggers, apply repellants to sleeves and cuffs of pants, as well as waistlines.

For more information on these little crimson menaces, see our EDIS publication at https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/IG085 or contact your local Extension office.

How often do we stop to think of the importance of pollinators to food security?

Pollination is often described as the transfer of pollen grains from the anther to the stigma of a flowering plant. These transfers are made possible due to pollinator visits in exchange of pollen and nectar from the plants.

Who are our pollinators?

Main Global Pollinators

Social Solitary

Honeybees Alfalfa leafcutter bee

Bumble bees Mason bees

Stingless bees Other leafcutter bees

How can we care for pollinators?

We can care for our pollinators by growing plants that have abundant and accessible pollen and nectar.

Choose plants with flat flowers or short to medium-length flowers tubes (corollas), and limit plants with long flower tubes such as honey suckle.

Avoid plant varieties that do not provide floral rewards (pollen), which is the essential food source for bees. (e.g., some sunflower, and lilies).

While we think of most flies as pests, garden flies, such as Allograpta obliqua species found in Florida, are excellent pollinators and insect predators. Photo by Jessica Louque, Smithers Viscient, Bugwood.org.

Many native wild bees have relatively short proboscises, or tongues, and may not be able to access nectar from flowers with long tubes; however, flowers with long floral tubes can attract other pollinators with long tongues or beaks such as butterflies, moths, and hummingbirds.

Are we creating an ecosystem aesthetically pleasing while attracting pollinators?

The planting of native wildflowers in Florida can benefit agricultural producers likewise, native pollinators and other beneficial such as parasitoids and predators.

Some of the main benefits of growing native wildflower are:

It is important to select mix varieties of native wildflowers when restoring habitats for our pollinators. Mix varieties will flower all year round and make available a continuous supply of nectar and pollen. If possible, use wildflower seeds that are produced in the state that you want to carry out pollinator restoration. It is highly likely that one will experience better growth from locally produced seeds because they will adapt better to regional growing conditions and the climate. For optimum flowering and high production of floral rewards such as pollen and nectar, place wildflowers in areas free of pesticides and soil disturbance.

Most bee species are solitary, and 70% of these solitary bees’ nest in the ground. A wildflower area of refuge can fulfill the shelter resource needs of these bees since that area will not undergo regular tilling, thus minimizing nest disturbance.

For some common native wildflowers of north Florida, you can see: Common Native Wildflowers of North Florida by Jeffrey G. Norcini : https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdf/EP/EP061/EP061-15448828.pdf and Attracting Native Bees to Your Florida Landscape 1 Rachel E. Mallinger, Wayne Hobbs, Anne Yasalonis, and Gary Knox: IN125500.pdf (ufl.edu)

Insects use pheromones to attract their mates and communicate with each other. Ants use pheromones to tell fellow ants where to find food. Aphids use pheromones to warn each other about potential predators. And all insects use pheromones to call for a mate.

So what exactly are pheromones? Pheromones are substances that are secreted by an individual and received by another individual of the same species. In humans, pheromones are most commonly found in sweat and detected by the olfactory system. Most animals have a functioning vomeronasal organ inside their noses to detect and process pheromones. However, it is debatable whether adult humans possess a functional vomeronasal organ.

Although most of us may not be able to detect insect pheromones, scientists have been able to identify and synthesize the pheromones of many economically important insects. These pheromones are impregnated on rubber and plastic dispensers and placed in different types of traps depending on the pest. The pheromone traps attract males of the target species. These traps are commonly used for monitoring, but in some cases can be utilized to disrupt mating habits which can help control some pests.

The most common pheromone trap in this part of the country is probably a boll weevil trap. Growing up, I thought they looked like little green lighthouses. These traps consist of a yellow-green cannister with an inverted funnel on top that contains the pheromone. While you may not be growing cotton in your home garden, there are some other common insect pests you may want to monitor and possibly disrupt.

Pecan Nut Casebearer (PNC) – These moths are gray with a dark line of scales on their forewings. PNC moths are about 1/3 inches long. They lay their eggs on the outside of pecan husks in April/early May. Their larvae bore into the base of developing nuts and remain inside the nuts for four to five weeks to feed then pupate. A tent-type trap with pheromone can be hung in a pecan tree in April or May to help monitor for this insect. Depending on how many trees you have, multiple traps can be installed to possibly disrupt the mating cycle of this pest.

Asian Citrus Psyllid (ACP) – These tiny insects are about the size of the tip of a pencil (about 1/8 inches long). They vector the Huanglongbing (HLB) disease also known as citrus greening. This disease blocks the nutrient uptake tissue of citrus trees and eventually kills infected trees. Traps consist of a yellow sticky card with a pheromone bait sometimes impregnated on the twist tie hanger. The citrus industry has been heavily impacted by citrus greening, so monitoring for this pest is very important.

Clearwing Moth – There are numerous species of clearwing moths that bore into the trunks of fruit and ornamental trees and shrubs. One of the most common is the peachtree borer. These insects don’t look like a typical moth. Instead, they resemble wasps. Tent-type pheromone traps can be used to monitor for clearwing moths and potentially disrupt their mating habits. Another common clearwing moth is the ash borer (lilac borer). As their name would suggest, these moths bore into the wood of ash trees, but they also like various Ligustrum species and olive trees.

These are just a few of the species of insects that can be monitored by pheromone traps. To help with the timing of trap dispersal and placement, you should get a grasp of concept of “Degree Days”. Degree day accumulation is used to predict important life events for particular insects such as the average egg laying date, egg hatch date, and larval development. More information on calculating degree days can be found in the article “Predicting Insect Development Using Degree Days” from the University of Kentucky. Fortunately for us, we can skip some of the math by utilizing the AgroClimate Growing Degree Days Calculator. Simply select the weather station closest to you on the provided map and a graph will appear.