by Matt Lollar | Oct 8, 2019

Last week at the Panhandle Fruit and Vegetable Conference, Dr. Ali Sarkhosh presented on growing pomegranate in Florida. The pomegranate (Punica granatum) is native to central Asia. The fruit made its way to North America in the 16th century. Given their origin, it makes sense that fruit quality is best in regions with cool winters and hot, dry summers (Mediterranean climate). In the United States, the majority of pomegranates are grown in California. However, the University of Florida, with the help of Dr. Sarkhosh, is conducting research trials to find out which varieties do best in our state.

In the wild, pomegranate plants are dense, bushy shrubs growing between 6-12 feet tall with thorny branches. In the garden, they can be trained as small single trunk trees from 12-20 feet tall or as slightly shorter multi-trunk (3 to 5 trunks) trees. Pomegranate plants have beautiful flowers and can be utilized as ornamentals that also bear fruit. In fact, there are a number of varieties on the market for their aesthetics alone. Pomegranate leaves are glossy, dark green, and small. Blooms range from orange to red (about 2 inches in diameter) with crinkled petals and lots of stamens. The fruit can be yellow, deep red, or any color in between depending on variety. The fruit are round with a diameter from 2 to 5 inches.

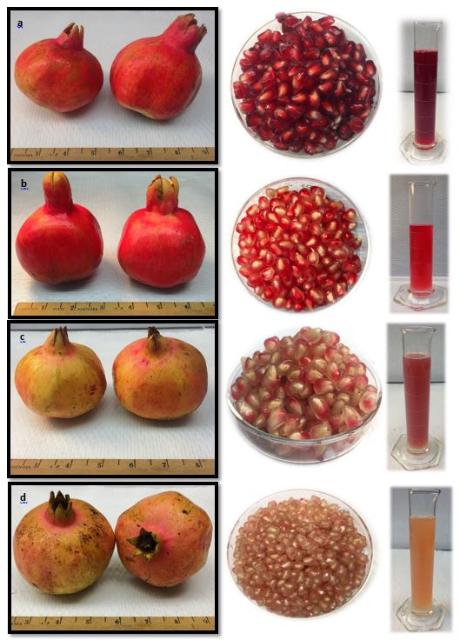

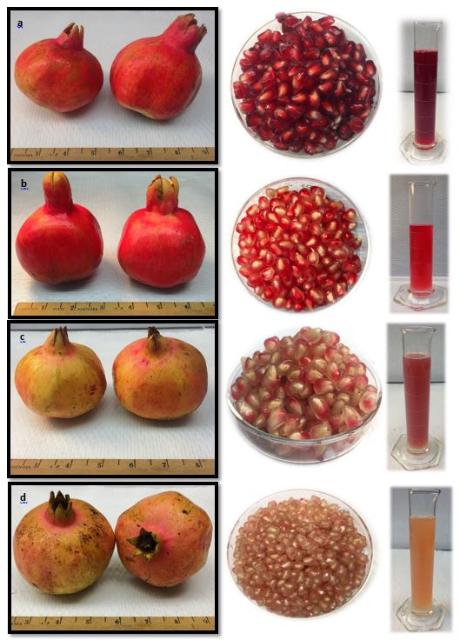

Fruit, aril, and juice characteristics of four pomegranate cultivars grown in Florida; fruit harvested in August 2018. a) ‘Vkusnyi’, b) ‘Crab’, c) ‘Mack Glass’, d) ‘Ever Sweet’. Photo Credit: Ali Sarkhosh, University of Florida/IFAS

A common commercial variety, ‘Wonderful’, is widely grown in California but does not perform well in Florida’s hot and humid climate. Cultivars that have performed well in Florida include: ‘Vkusnyi’; ‘Crab’; ‘Mack Glass’; and ‘Ever Sweet’. Pomegranates are adapted to many soil types from sands to clays, however yields are lower on sandy soils and fruit color is poor on clay soils. They produce best on well-drained soils with a pH range from 5.5 to 7.0. The plants should be irrigated every 7 to 10 days if a significant rain event doesn’t occur. Flavor and fruit quality are increased when irrigation is gradually reduced during fruit maturation. Pomegranates are tolerant of some flooding, but sudden changes to irrigation amounts or timing may cause fruit to split.

Two pomegranate training systems: single trunk on the left and multi-trunk on the right. Photo Credit: Ali Sarkhosh, University of Florida/IFAS

Pomegranates establish best when planted in late winter or early spring (February – March). If you plan to grow them as a hedge (shrub form), space plants 6 to 9 feet apart to allow for suckers to fill the void between plants. If you plan to plant a single tree or a few trees then space the plants at least 15 feet apart. If a tree form is desired, then suckers will need to be removed frequently. Some fruit will need to be thinned each year to reduce the chances of branches breaking from heavy fruit weight.

Anthracnose caused by Colletotrichum sp. to pomegranate fruit. Photo Credit: Gary Vallad, University of Florida/IFAS

Anthracnose is the most common disease of pomegranates. Symptoms include small, circular, reddish-brown spots (0.25 inch diameter) on leaves, stems, flowers, and fruit. Copper fungicide applications can greatly reduce disease damage. Common insects include scales and mites. Sulfur dust can be used for mite control and horticultural oil can be used to control scales.

by Julie McConnell | May 17, 2019

Walking around my yard I’m always on the lookout for changes – both good and bad. I look to see which plants are leafing out or flowering. I scout for plant disease symptoms, insect damage, and weeds. I’ve learned over the years that when I spot a plant out-of-place before condemning it as a weed, I need to make sure it isn’t really a bonus plant!

This spring my yard has really changed. After losing numerous mature trees the sun is shining in new spots. Last fall I also had a bit of unexpected seed and vegetation dispersal to say the least, so I’m getting lots of surprises in the landscape. A few bonus plants I’m seeing and leaving alone are oak seedlings, black-eyed Susan, sunflowers, Angelina sedum, dotted horsemint, and verbena.

These plants might not be exactly where I would have placed them, but if they are not located somewhere that will be a maintenance problem, they can stay where they landed. Many of these plants are taking advantage of dry, non-irrigated sites and providing welcome vegetative groundcover that will help prevent erosion. The bonus is that they all provide food or shelter for birds and/or bugs!

How do you tell the difference between a weed and a plant you would like to keep? The key is to pay attention to plant features other than flowers. Start looking at foliage shape, texture, color, growth habit, and how leaves are arranged on the plant. Other characteristics are stem color and shape – some plants have square stems, others have ridges we refer to as “wings” in horticulture terms, tendrils on vines, all of these can be distinctive and recognizable before the obvious flowers form. Keep notes with pictures of plants at different life stages until you commit them to memory. Eventually you’ll be able to walk through your landscape and quickly note the differences which will help conserve those bonus plants and get weeds under control before they get too prolific.

Below are links to sites that might be outside your regular bookmarks. These resources show more than just the pretty flowers and have detailed information on life cycle and growing conditions.

by Mark Tancig | Sep 6, 2018

A grape vineyard. Credit: Peter Andersen, UF/IFAS.

The classic muscadine (Vitis rotundifolia). Credit: Carl Hunter. USDA-PLANTS Database.

This is the time of year to be on the watch for purple-stained sidewalks and driveways – a sign that ripe muscadine grapes are falling from above. The muscadine grape (Vitis rotundifolia) is a native Florida vine that has been enjoyed by Native Americans, colonists, and contemporary Floridians alike. In addition to the classic muscadine and scuppernong, a light-colored variety of muscadine, there are five other native species of grape (Vitis spp.) to be found growing in natural areas or along woodland edges. All are edible, however, the muscadine has the largest, tastiest fruit.

Many north Florida gardeners have some species of grape growing in their landscapes and consider it a weed due to its aggressive growth. Unfortunately, since the vines are functionally dioecious (separate male and female plants) and most wild plants are male, it is unlikely that those annoying grapevines at the garden’s edge will ever bear fruit. But every now and again, luck strikes! That’s why finding a purple-stained sidewalk or parking area is such an exciting event. I have some of these locations saved in my memory to visit this time of year, especially since all the grapevines in my own property have yet to bear one fruit! If necessary, control methods for grapevine in a landscape include repeated pruning back or the use of herbicides. Muscadines and other grapes are intolerant of shade so will eventually perish if cut back and located under a canopy of trees or shrubs.

The bronze-colored scuppernong. Credit: Peter Andersen. UF/IFAS.

Good News! There are plenty of varieties bred for the backyard and commercial fruit grower. Since muscadines are native, they require little, if any, pesticides, making them a great choice for a sustainable landscape or orchard. The vines can be grown up an arbor or a complete vineyard trellis system can be built for maximum harvest. A UF/IFAS fact sheet called “The Muscadine Grape” (publication #HS763) contains all the information needed to choose the right variety, design a vineyard, and implement the best pruning, irrigation, and fertilization schedule.

Whether fresh off the vine or in jams or wine, muscadines are a sweet, summery treat for Floridians.

by Mark Tancig | Jul 11, 2018

Guest Post by Leon County Family & Consumer Sciences Agent Heidi Copeland (pictured)

Guest Post by Leon County Family & Consumer Sciences Agent Heidi Copeland (pictured)

With all the rain of late, there seems to be an interest in mycology. You know, the fruiting body of fungi called mushrooms! Edible mushrooms in particular.

It is not unusual; our subtropical summer weather tends to make some fungi flourish! Moreover, apparently, there is a bumper crop of fungi this year. Phone calls to the University of Florida/IFAS Extension office about eating mushrooms has increased. Individuals have even brought mushrooms to the office inquiring if they are of the edible variety.

Our reputation as Extension Agents would certainly be damaged if we did not adhere to a few rules… always read a label, use research-based information, and NEVER tell anyone that a mushroom is edible. It is not that there are not delicious wild mushrooms out there; a recent July 2017, publication of Microbiology Spectrum estimates millions of species. However, even the scientists do not agree as only about 120,000 of them have been described, so far. Not all are edible. Some fungi are poisonous to the point of being deadly.

Matt Smith, an Assistant Professor in the Department of Plant Pathology and the curator of the UF Fungal Herbarium (FLAS) knows a lot about mycology. In fact, he is also the curator of the fungal herbarium managed by the UF Department of Plant Pathology at the Florida Museum of Natural History in Gainesville. The fungal herbarium is a valuable resource and its collections have many important aspects including information about fungi that are deadly poisonous to humans and pets when consumed.

Lion’s Mane mushroom. Credit: Robert Smith; Cabin Bluff Land Management; Bugwood.org

In addition, the UF fungal herbarium is participating in a National Science Foundation-funded project to digitize and database as many US macrofungi collections as possible. This project, the Macrofungi Collection Consortium, includes 34 institutions in 24 states. The project began in July 2012 and will aim to capture data for roughly 1.3 million fungal specimens.

With that said, there is enough scientific research out there to conclude mushroom identification is indeed difficult. Many mushrooms look similar, but are oh so different!

If you are truly interested in eating what you forage MAKE time to study, with experts! Mushrooms, particularly those you plan to eat that are not identified correctly could send you to the emergency room … or worse. The toxicity of a mushroom varies by how much has been consumed. Poisoning symptoms range from stomachaches, drowsiness and confusion, to heart, liver and kidney damage. The symptoms may occur soon after eating a mushroom or can be delayed for six to 24 hours.

Chanterelle mushroom. Credit: Chris Evans; University of Illinois; Bugwood.org

Delayed symptoms are common. Seek help immediately if you think you may have eaten a poisonous mushroom, even if there are no obvious signs of toxicity. Call the Poison Center’s 24-hour emergency hotline at 1-800-222-1222. You will receive immediate, free and confidential treatment advice from the poison experts.

And if you are determined to make foraging for food a recreational hobby or even want to learn more about what is in your Florida yard, the book Common Florida Mushrooms by University of Florida’s Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences Emeritus Faculty Dr. James Kimbrough, identifies and describes 268 species of mushrooms found in the sunshine state.

Most importantly, teach your children to NEVER eat any mushroom picked from the ground. It is indeed better to be SAFE than sorry.

People who are interested visiting the fungal herbarium should contact:

Dr. Matthew Smith

email: trufflesmith[nospam]@ufl.edu

by Gary Knox | Nov 25, 2014

View of the Discovery Garden in Gardens of the Big Bend.

Weeping false butterflybush, Rostrinucula dependens, is a new and unusual perennial being evaluated in Gardens of the Big Bend.

Gardens of the Big Bend is a new botanical and teaching garden located on the grounds of the University of Florida/IFAS North Florida Research and Education Center in Quincy. The goals of these gardens are to evaluate new plants, promote garden plants adapted to the region, demonstrate environmentally sound principles of landscaping and provide a beautiful and educational environment for students, visitors, gardeners and Green Industry professionals.Located just 10 miles south of the Georgia-Florida border in Florida’s “Big Bend,” the Gardens are in USDA Cold Hardiness Zone 8b and have sandy-clay soils more typical of continental conditions than those of peninsular Florida.

Gardens of the Big Bend is a series of gardens, each with a theme or plant focus:

- The Discovery Garden contains over 170 species or cultivars of new, improved or underutilized trees, shrubs and perennials. The garden’s purpose is to help gardeners, landscapers and nursery growers “discover” new plants.

- The Magnolia Garden is part of the National Collection of Magnolia in recognition of its’ more than 200 species and cultivars, including some of the rarest magnolias in the world.

- The Crapemyrtle Garden includes six species and over 100 cultivars.

- Conifers can be found throughout the Gardens but are featured in the new “Jurassic” garden. More than just pines and junipers, the Gardens contain over 50 conifer species and cultivars, many of which are rare. In recognition, the American Conifer Society has designated the Gardens as a “Conifer Reference Garden”, the only one in Florida, and the southernmost in the U.S.

- The Dry Garden is the newest addition and contains about 140 different types of agave, aloe, cactus, dyckia, sedum, yucca, bulbs and other dry-adapted plants. It consists of a south-facing berm of boulders, gravel and sand about 160 feet long, 35 feet wide and 6 feet tall.

- Other gardens feature native, shade, Southern heritage, and weeping plants as well as collections of Japanese hydrangea and shrub roses. Additional gardens will be installed as time and funding permit.

Parana pine, Araucaria angustifolia, is a rare type of conifer in the Gardens.

Gardens of the Big Bend formally began in 2008 thanks to the happy marriage of a new volunteer organization coupled with this University of Florida off-campus facility and plant collections I developed as part of research and extension projects. The volunteer organization, Gardening Friends of the Big Bend, Inc., formed in 2007 to support horticulture research and education. This group quickly seized on the idea of transplanting these existing plant collections into a series of gardens. Accordingly, its members hold fundraisers, provide volunteer labor and sponsor extension programs to raise awareness, provide funds and support garden development and maintenance.

Gardens of the Big Bend is located in Quincy at I-10 Exit 181, just 1/8 mile north on Pat Thomas Highway (SR 267). The gardens are free and open to the public during daylight hours year-round; professional staff are only available during normal business hours. To make a gift to the Gardens, please go to this website! Come visit us and watch the Gardens grow!