by Laura Tiu | Mar 31, 2017

By: Laura Tiu and Sheila Dunning

For the second year in a row, University of Florida Extension Agents Sheila Dunning (horticulture) and Laura Tiu (marine science) taught a Florida Master Naturalist Program (FMNP) Coastal Module to a newly recruited AmeriCorps group in Okaloosa and Walton counties. The AmeriCorps members have been recruited to work with local the non-profit Choctawhatchee Basin Alliance during the 2016-17 school year teaching Grasses in Classes and Dunes and Schools at the local elementary schools.

AmeriCorp volunteers learning about coastal environments by attending the Florida Master Naturalist class.

Photo: Laura Tiu

As part of the training, FMNP students participated in an aquatic species collection training to enable them to collect species for touch tanks used throughout the school year. At the training, we met two Fort Walton Beach High School science teachers. Teachers Marcia Holman and Ashley Daniels (an AmeriCorps 2013 member herself) were surprised to see two former students in our AmeriCorps 2016 FMNP class; Dylan and Kaitlyn. Dylan, they reported, was a student that many teachers worried about during his freshman year. However, he just blossomed because of his involvement in the marine classes and environmental ecology club. They were most proud of his leadership designing and implementing a no-balloon graduation ceremony. This prevented the release of potentially harmful balloons into our coastal waterways where they pose a hazard to marine life.

The teachers were so happy to see both students had joined AmeriCorps and were receiving FMNP training. They realized that they were making a difference in the lives of their students and the students they had trained were working to preserve and protect the environment in their communities. When asked if they had any other students that we need to be prepared for Holman replied, “It’s hard to tell at this point in the year if we have any rising marine science stars, but we did have 20 kids show up for the first meeting of the ecology kids club.” We can’t wait to meet them.

by Judy Biss | Mar 17, 2017

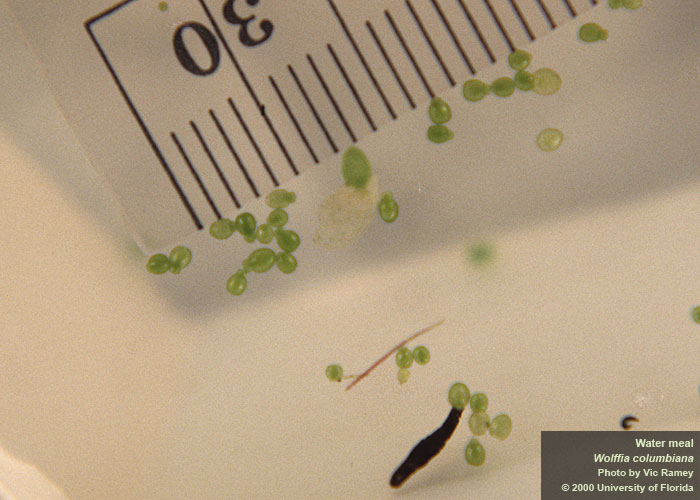

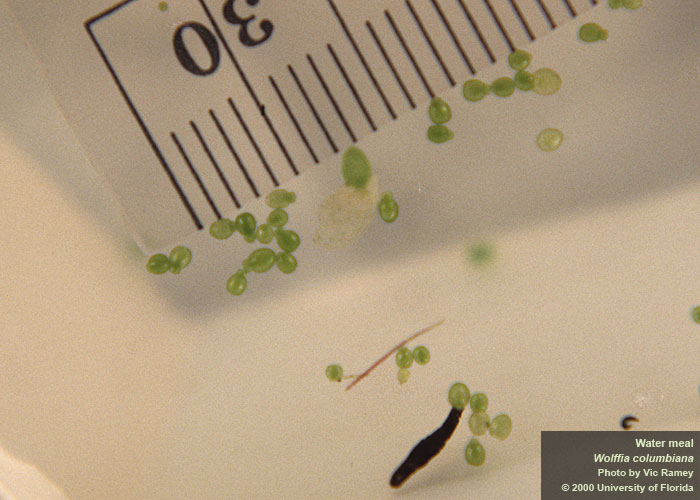

Water meal, the world’s smallest flowering plant. Photo by Vic Ramey, University of Florida/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. Used with permission.

Some of the world’s smallest flowering plants grow in aquatic environments. And a number of these tiny aquatic plants grow natively right here in Florida! Aquatic plants of all kinds display an amazing array of adaptations for growing in water. They can tolerate drought, flood, flowing water, stagnant water, cold spring runs, and warm brackish marshes. They grow in sun and shade and nutrient rich to nutrient poor waters. Some of their adaptations include the ways in which they grow such as being rooted in bottom sediments, submerged, emerged, leaves floating on the surface, or completely free floating with their roots dangling into the water below.

The tiniest of aquatic plants are in this group of free floating plants. Let’s take a look at five of these tiny (less than ½ inch wide) plant species in Florida. They are most noticeable in slow moving waters, ponds, or coves protected from wind where many thousands of them form floating mats almost like paint on the water surface. Even though individual plants are small, some of these plant species are used by wildlife and invertebrates for food and cover. Oftentimes, especially in small ponds, these tiny floating plants can cover the entire water surface resulting in the need for management, especially if the ponds are used for irrigation or livestock watering.

In this article we will look at the native species, but as you are probably aware, there are also non-native representatives of these tiny plants established in our waters, but that is a story for another time…

The images and text below are from the UF/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Species website, list of Plants Sorted by Common Name.

Watermeal

“Water meal, native to Florida, is a tiny, floating, rootless plant. At 1 to 1.5 mm long, it is the smallest flowering plant on earth. It is occasionally found growing in rivers, ponds, lakes, and sloughs of the peninsula and central panhandle of Florida (Wunderlin, 2003).”

Water meal has a grainy feel and can be used as one clue in identifying this plant. Photo by Ann Murray, University of Florida/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. Used with permission.

American Waterfern

“There are six species of Azolla in the world. American waterfern is the species commonly found in Florida. American waterfern is a small, free-floating fern, about one-half inch in size. It is most often found in still or sluggish waters. Young plants are, at first, a bright or grey-green. Azolla plants often turn red in color. American waterfern can quickly form large, floating mats.”

A large area of waterfern showing the reddish coloration. Photo by Vic Ramey, University of Florida/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. Used with permission.

Close up of individual water fern plants. Photo by Ann Murray, University of Florida/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. Used with permission.

Giant Duckweed

“Giant duckweed is a native floating plant in Florida. Though very small, it is the largest of the duckweeds…..frequently found growing in rivers, ponds, lakes, and sloughs from the peninsula west to the central panhandle of Florida (Wunderlin, 2003)… Giant duckweed has two to three rounded leaves, which are usually connected. Giant duckweeds usually have several roots (up to nine) hanging beneath each leaf. The underleaf surface of giant duckweed is dark red.”

Close up of individual duckweed plants showing roots hanging freely below the plant. Photo by Vic Ramey, University of Florida/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. Used with permission.

A typical scene of duckweed in a quiet cove or pond. Photo by Ann Murray, University of Florida/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. Used with permission.

Small Duckweed

“Small duckweeds are floating plants. They are commonly found in still or sluggish waters. They often form large floating mats…. Small duckweeds are tiny (1/16 to 1/8 inch) green plants with shoe-shaped leaves. Each plant has two to several leaves joined at the base. A single root hangs beneath.”

This is small duckweed, note the single root below each plant. Photo by Vic Ramey, University of Florida/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. Used with permission.

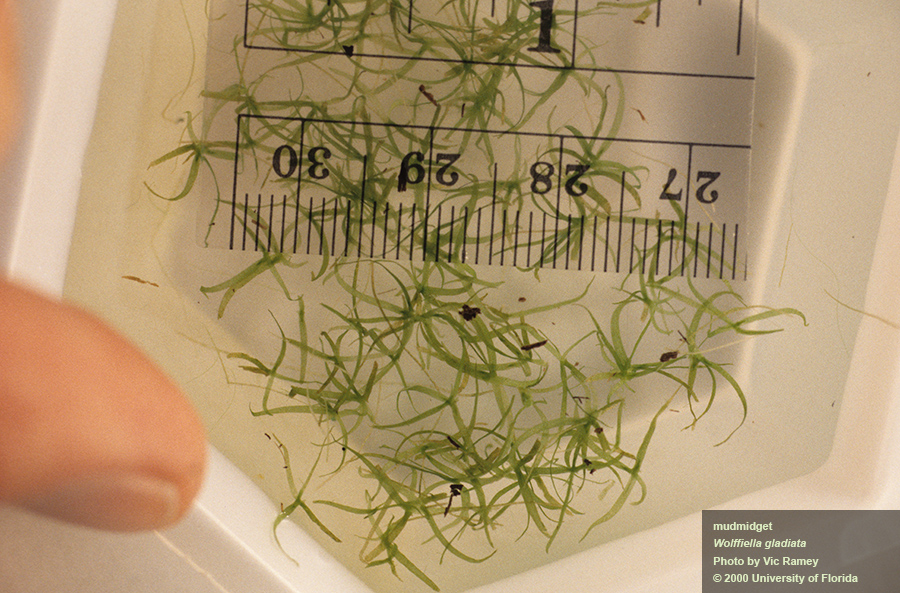

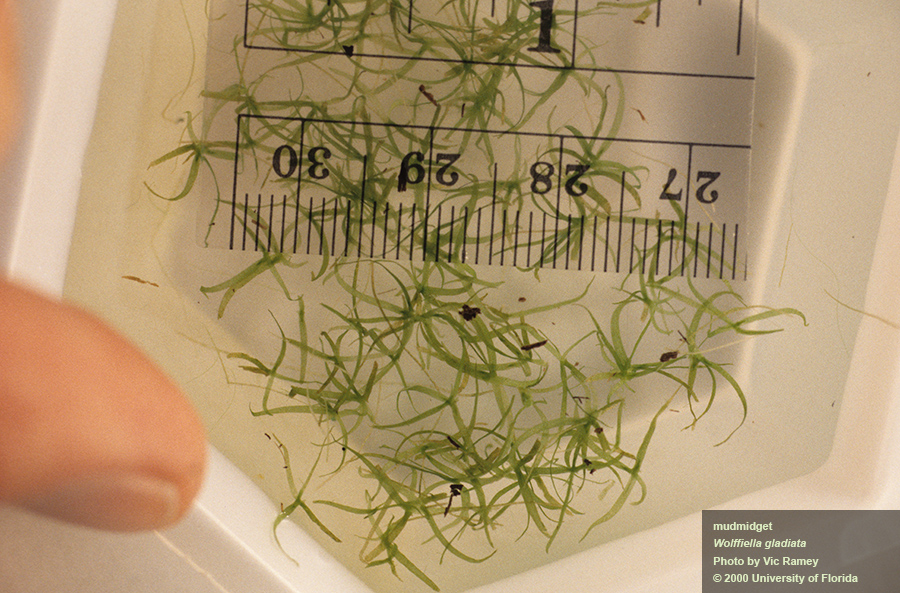

Mudmidget

“Mud-midget, native to Florida, is another small duckweed, but this one has narrow, elongated fronds. The fronds are usually connected to form starlike colonies. The fronds are 5-10 mm long; the flowers are extremely small and difficult to see. Mud-midget plants float just beneath the surface of the water and is frequently found growing in rivers, ponds, lakes, and sloughs from the peninsula west to the central panhandle of Florida (Wunderlin, 2003)….”

Mudmidget, Photo by Vic Ramey, University of Florida/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. Used with permission.

If you have any questions about aquatic plant identification or management options, please contact your local UF/IFAS Extension County office. And, for more information on Florida’s aquatic plants, please see the following resources used for this article:

UF/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Species

Plants Sorted by Common Name

USDA Forest Service – Duckweed

USDA Forest Service – Water Fern

Native Aquatic and Wetland Plant Fact Sheets

Aquatic Plant Identification List with Pictures and Videos

by Judy Biss | Mar 17, 2017

Beaver lodge, Calhoun County Florida. Photo by Judy Biss

Even though the “work” beavers do can sometimes cause frustration to land owners, they are truly amazing creatures. A number of questions have come into the Extension Office lately about managing beavers, so it is a good time to discuss a little about the history and biology of these unique animals, as well as the management options available for land owners.

Beavers in the American Landscape

Hundreds of millions of beaver once occupied the North American continent until the 1900s, when the majority had been trapped out in the eastern United States for the fur trade (Baker, B.W., and E.P. Hill. 2003. Beaver (Castor canadensis)). “Growing public concern over declines in beaver and other wildlife populations eventually led to regulations that controlled harvest through seasons and methods of take, initiating a continent-wide recovery of beaver populations.” (Baker, B.W., and E.P. Hill. 2003. Beaver (Castor canadensis)). In its current range, the beaver “thrives throughout the Florida Panhandle and upper peninsula in streams, rivers, swamps or lakes that have an ample supply of trees.” (Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, Aquatic Mammals, Beaver: Castor canadensis).

Adaptations

Beavers are the largest rodent in North America. In Florida, they commonly weigh between 30 – 50 pounds. Beavers are considered an aquatic mammal, having adaptations such as a streamlined shape, insulating fur, ears and nostrils that close while underwater, clear membranes that cover their eyes while underwater, large webbed feet, and a broad flat rudder-like tail that aid in swimming. They can remain underwater for 15 minutes at a time! Their tree-cutting, bark-peeling front teeth grow continuously, and as a result, are continuously sharpened as they grind against the lower teeth. (Baker, B.W., and E.P. Hill. 2003. Beaver (Castor canadensis), Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, Aquatic Mammals, Beaver: Castor canadensis).

Habitat and Behaviors

Beavers typically mate for life and live in family groups consisting of the adult male and female, and one or two generations of young kits before they are old enough to disperse on their own. They are primarily nocturnal, being active from dusk to dawn. Beavers eat not only tree bark, leaves, stems, buds, and fruits, but herbaceous plants as well. Their diet is broad and can consist of aquatic plants, such as cattails and water lilies, shrubs, willow, grasses, acorns, tree sap, and sometimes even cultivated row crops. (Baker, B.W., and E.P. Hill. 2003. Beaver (Castor canadensis)).

Top of beaver dam in Calhoun County FL. Water level difference is nearly 3 feet. Photo by Judy Biss

Dam and Lodge Construction

The sound of moving water triggers beavers to build, repair, or maintain their dams. (Baker, B.W., and E.P. Hill. 2003. Beaver (Castor canadensis)). The two main structures they build are the water-slowing dam and their living quarters or lodge. The lodge is separate from the dam and is oftentimes located in the stream or pond bank. “The ponds created by dams also provide beavers with deep water where they can find protection from predators — entrances to dens or lodges are usually underwater. Some beavers in Florida do not build the massive stick lodges associated with northern colonies. Instead, they are more likely to live in deep dens in stream banks…” Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, Aquatic Mammals, Beaver: Castor canadensis).

Pear tree felled by beaver in Calhoun County FL. Photo by Judy Biss

Impacts

Beavers are called “nature’s engineers” for good reason. Their tree cutting and building behaviors certainly alter surrounding landscapes. Outside of any connection to human civilization, their activities tend to increase diversity and habitat options for both plants and animals. Many scientists have examined the intricate biological and ecological effects beavers have on surrounding landscapes. Their activities in our backyard, however, do not always result in positive outcomes. Often, beavers are triggered to build dams in running water through road culverts causing significant impacts to road drainage, and surrounding flood management. Their construction of dams along creeks can flood farm fields and woodlands. Their feeding and tree cutting can kill desired trees in nearby timberland and orchards.

Management Options for Land Owners

The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) publication, “Living with Beavers” provides excellent advice, along with a summary of the regulations regarding this native wildlife species. As per this document, “The beaver is a native species with a year-round hunting and trapping season in Florida.” Beaver hunting and trapping regulations can be found on the FWC Furbearer Hunting and Trapping website. A beaver can be taken as a nuisance animal, if it causes or is about to cause property damage, presents a threat to public safety, or causes an annoyance in, under, or upon a building, per Florida Rule 68A-9.010.” Other recommendations from this FWC publication are:

- “Beaver dam removal provides immediate relief from flooding and can be the simplest and cheapest way of dealing with a beaver problem. However, beavers often quickly rebuild a dam as soon as it is damaged. “

- “When removing a dam is infeasible or unsuccessful, installing a water level control structure through the dam can allow for the control of water flow without removing the dam. This technique also reduces the likelihood of the beaver continuously blocking water flow. For technical assistance, contact a wildlife assistance biologist at a regional FWC office near you.”

- “If a beaver dam is blocking a culvert or similar structure, installing a barrier several feet away from the culvert can be the most effective solution. This prevents the beavers from accessing the culvert to dam it. Please contact a wildlife assistance biologist at a regional FWC office near you for technical assistance.”

- “Protect valuable trees and vegetation from beaver damage by installing a fence around them or wrapping tree trunks loosely with 3-5 feet of hardware cloth or multiple wraps of chicken wire. This prevents the beavers from chewing on the trees and other plants.”

- “Lethal control should be considered a last resort.”

FWC also points the reader to this publication from Clemson University Cooperative Extension Service, Department of Aquaculture, Fisheries and Wildlife, “The Clemson Beaver Pond Leveler.” This publication provides diagrams and a list of materials needed to construct a device which is designed to “minimize the probability that current flow can be detected by beavers, therefore minimizing dam construction.”

All questions regarding beaver management should be directed to your local FWC Regional Office. Land owners can also request a list of Nuisance Wildlife Trappers available in their area:

FWC Northwest Region Office

3911 Highway 2321

Panama City, FL 32409-1659

(850) 265-3676

Links to the references used for this article:

by hollyober | Mar 17, 2017

Bluebirds are very energetic birds. If you enjoy watching wildlife in your yard, now is a fantastic time to put up a few bluebird houses. You might gain hours of entertainment watching all the hard work these small birds put into gathering materials to build nests and gather food to feed their chicks.

In the Panhandle, bluebirds begin in March to create their first nests of the year. They carefully weave a basket of pine needles and twigs, and line it with fine grasses. Photo by Holly Ober.

March is when bluebird nest-building begins in the Panhandle. Believe it or not, these enterprising birds are likely to continue building nest after nest from now through July or even August!

The reason we can observe bluebirds more closely than many other birds is because they prefer to nest in cavities situated in open, sunny locations. These birds readily use nest boxes because natural cavities in clearings are quite scarce.

If you’re considering putting up a nest box to attract bluebirds, be aware that these birds are rather fussy when it comes to selecting nest boxes. They prefer structures that are approximately 4”x4”x9” or 5”x5”x9”. These structures could be rectangular, cylindrical, or wedge-shaped. It’s best if the entrance hole is 1.5” in diameter, and located about 5” above the floor of the box. Each house should be mounted on a pole 4-8’ above the ground.

We have been conducting an experiment the past few years to determine which of three common nest box designs local bluebirds prefer. The three types of houses we tested were:

- traditional wooden rectangular house (4”x4”x9”)

- Gilbertson (cylindrical houses made of a PVC tube with a wooden floor and roof)

- Peterson (wedge-shaped houses made of wood and covered in metal, with a sloping floor and roof).

We tested bluebird preferences for 3 types of houses: the traditional rectangular wooden house (left), the Gilbertson (cylindrical house of PVC, center), and Peterson (wooden wedge-shaped, right).

We put up 18 houses during the summer of 2013 and have been keeping track of the number of nest attempts, eggs laid, and chicks fledged ever since. The ambitious birds using these 18 houses have fledged 124 chicks during the past three years! The standard rectangular wooden houses have performed best, with bluebirds laying an average of 8.3 eggs per house per year, and fledging 4.3 chicks per house per year. The other two house types performed similarly, with bluebirds laying an average of 4.3 eggs per house per year in each. An average of 2.4 chicks fledged from each of the Gilbertson houses each year, whereas 1.8 chicks fledged from each of the Peterson houses each year.

Regardless of which type of house you choose to put up for bluebirds, be sure to place the houses at least 100 yards apart. These birds are very territorial and will not allow other bluebirds to nest nearby.

by Laura Tiu | Mar 11, 2017

There has been an increasing demand by clientele for information and training on small-scale food production methods to meet the growing demand for locally produced food and for personal consumption. One of the University of Florida Extension’s high-priority initiatives is “increasing the sustainability, profitability, and competitiveness of agricultural and horticultural enterprises.” One food production method currently being investigated is aquaponics.

Koi are a popular fish species used in aquaponic systems.

Photo: Laura Tiu

Aquaponics is a technique for sustainable food production that utilizes the combination of aquaculture with hydroponics to grow fish and vegetables without soil. The process begins with fish producing waste, which is then pumped through a bio-filter to convert into fertilizer for the plants. Plants use nutrients from that water, and the freshly oxygenated water is returned to the fish tank. By recirculating the water from the fish tank to the grow bed, the need for water is greatly reduced compared to traditional irrigation. Additionally, producing crops aquaponically can reduce leaching, runoff, and water discharges to the environment by reusing nutrient effluent from aquaculture and hydroponic systems.

For new growers, being able to have access to training and to see a demonstration unit can eliminate many of the pitfalls typically encountered. A small aquaponics system, using local-sourced materials, is being constructed at the Walton County Extension office in DeFuniak Springs, FL. This system will demonstrate the technology and capability of small-scale aquaponics. The system is expected to be operational in April 2017. Working together, the Sea Grant, Horticulture, and Agriculture agents will be able to share construction and operation information with interested clients. Data will be collected from the system in order to give clientele real-world expectations of the operating costs and production potential from the system. Information will be shared in face-to-face interactions, at workshops, via webinar and in published articles. The goal is to see an increase in the number of aquaponics operations in the Panhandle of Florida contributing to an increase in availability of locally and sustainably produced food.

If you would like to see the system or learn more about aquaponics by subscribing to our Aquaponics list serve, please email Laura Tiu, lgtiu@ufl.edu.

Greens tend to do very well in aquaponic systems.

Photo: Laura Tiu

A panhandle favorite, tomatoes can be grown using aquaponics.

Photo: Laura Tiu