by Erik Lovestrand | Jul 9, 2021

Summertime in North Florida is an awesome time of year if you like to harvest and prepare your own seafood from local waters. In my area, around Wakulla and Franklin County, scallop season runs from July 1 – September 24. In St. Joseph Bay, another popular scalloping area in Gulf County, the season spans from August 14 – September 24. Therefore, in the spirit of “sharing the love,” here is my recipe for a day with family and friends that you will never forget and will eagerly anticipate repeating each year as summertime approaches.

Two parts: “local knowledge”

– Study boating access points and local water depths/tides

– Talk to locals about the best places to find scallops

– Ask others for their favorite scallop recipes

One part: “the right gear”

– Masks, snorkels and mesh bags are a must

– Dive fins and small dip nets are helpful

– Dive flag on display is required when swimming

– Bring a bucket for measuring your catch

One part: “a little luck”

– Sunny days and clear water are best for seeing scallops down in the seagrasses

– Winds below 10 knots make boating and snorkeling more pleasant

Two parts: “paying attention to the details”

– Know the rules on Licenses, gear, limits and season dates

– Conduct equipment checks on snorkel gear, boat/trailer, and required safety gear

– Boat safely and cautiously near swimmers and over shallow seagrass beds

– Keep young children close, watch the weather, and know local hazards for boaters

– Don’t forget the sunscreen, snacks, and adequate hydration for all

A healthy pinch: of “enthusiasm,” with a helping attitude for first-timers

– From the first one you spot nestled down in the seagrass, to the last one of the day, you will never tire of the thrill

– Reassure first-timers that the seagrass is a fascinating environment, not a scary place, by showing them its wonders (i.e. sea stars, burrfish, spider crabs, and much, much more)

– Teach proper shucking technique with a curved blade to avoid wasted meat

Yield: A full day of memories and an incredible culinary experience.

– A limit of scallops is two gallons (in the shell) per person currently, with no more than 10 gal per boat. Ten gallons of scallops in the shell will allow you to fix a feast of scallops, prepared several ways. We like to marinate some in Italian dressing then grill on skewers, sauté a batch with garlic and butter, and deep fry some with a light breading. Throw in a fresh batch of cole slaw, some hush puppies and laughter around the table to top it off and your day will have been a true success. Oh, I will also say that you will be thoroughly exhausted and will probably get one of your best nights of sleep since last summer’s scallop season.

by Erik Lovestrand | Jun 3, 2021

Identifying North Florida river turtles can be quite challenging, given the fact that several species are collectively referred to as “streak-ed heads” by many people. Although you will not find this term in the scientific naming conventions, it is actually an apt description for many turtles in the Southeast that have dark skin with thin, yellow pinstripes on their head and neck. North Florida has at least half a dozen species that fall into this general grouping. They include the Suwannee cooter, river cooter, Florida cooter, chicken turtle, yellow-bellied slider and a couple of map turtles. We even have a disjunct population of Florida red-bellied turtles on the Apalachicola River that are isolated from the main group, which is restricted to peninsular Florida and extreme Southeastern Georgia. Overall, we have about 25 species of turtles in Florida.

Suwannee cooters at Lafayette Blue Springs, Lafayette County, Florida, 2021.

FWC Photo by Andy Wraithmell

As you might guess, the key to accurate river turtle identification lies in the details and the details can be tough to see. Most basking turtles tend to tumble off their logs into the water long before you are close enough to scrutinize their features. However, a few tips and tricks may improve your chances when going afield. A good pair of binoculars and a reptile field guide are must-haves. You need to be able to see if the yellow on the side of the head is a wide splash (as on the yellow-bellied slider), or a series of thin lines (as on various cooters). If the top shell (carapace) is very dark and the bottom shell (plastron) shows orange color, you might have a red-belly or Suwannee cooter (higher dome on red-belly, relatively). Two of our native species have what are referred to as “striped breeches”. When viewed from the rear, the stripes on the hind legs are vertically oriented on the yellow-bellied slider and the Florida chicken turtle. The chicken turtle is distinguished by a relatively narrower head and a wide, yellow stripe on the front legs. Separating the various cooter species gets a little trickier. You need to use characteristics like the pattern on the plastron, the occurrence of “hairpin-shaped” stripes on the head, or the pattern of lines on particular carapace scutes.

So how do you get those clues in the wild? A good telephoto lens may work if you are fortunate enough to own one. This will give you the opportunity to study detailed features at your leisure. Otherwise, you may not be able to identify a turtle to the species level. Getting close to a wary turtle is not easy. However, on busy stretches of our waterways, where wildlife are desensitized to people and boats, turtles generally have a wider comfort zone. Especially if you are in a canoe or kayak and minimize your movement and sound as you glide in for a better view. Lastly, go looking on a bright sunny day and your opportunities will vastly increase as turtles climb out of the water onto logs to soak up some of that good old Florida sunshine. One species that you should have no trouble naming when encountered, is the softshell turtle. Softshells will extend their extremely long neck upward when basking and their flexible, smooth shell will appear flattened in profile. They are the only turtles here with a tubular snout. Never try to pick one up if encountered crossing a road, as they do not hesitate to bite and have extremely sharp and powerful jaws. In general, even if you are confident in not getting nailed, you will probably be wrong, given the extremely long neck that can reach more than halfway back on the shell. Also, all of our water turtles have very sharp claws on their hind feet and will manage to get in a few good rakes before you decide to put them down, or worse yet, drop them on the pavement and injure them.

Now, when you think you are getting good at basking turtle identification, start looking for some of our less obvious, smaller species. These include stinkpots, musk turtles, mud turtles, map turtles and box turtles; all very cool critters. But if you think you want to pick up one of the cute little buggers, beware. Most of the little ones will bite too…hard! Believe me. Happy “turtling!”

by Erik Lovestrand | Mar 11, 2021

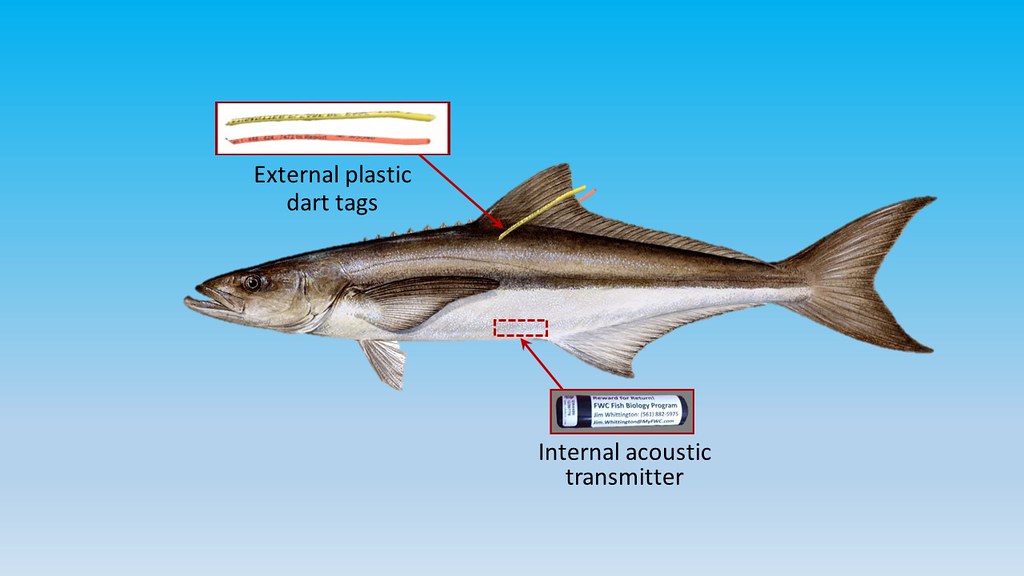

Cobia Researchers use Transmitters as well as Tags to Gather Data on Migratory Patterns

I must admit to having very limited personal experience with Cobia, having caught one sub-legal fish to-date. However, that does not diminish my fascination with the fish, particularly since I ran across a 2019 report from the Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission titled “Management Profile for Gulf of Mexico Cobia.” This 182-page report is definitely not a quick read and I have thus far only scratched the surface by digging into a few chapters that caught my interest. Nevertheless, it is so full of detailed life history, biology and everything else “Cobia” that it is definitely worth a look. This posting will highlight some of the fascinating aspects of Cobia and why the species is so highly prized by so many people.

Cobia (Rachycentron canadum) are the sole species in the fish family Rachycentridae. They occur worldwide in most tropical and subtropical oceans but in Florida waters, we actually have two different groups. The Atlantic stock ranges along the Eastern U.S. from Florida to New York and the Gulf stock ranges From Florida to Texas. The Florida Keys appear to be a mixing zone of sorts where Cobia from both stocks go in the winter. As waters warm in the spring, these fish head northward up the Atlantic and Gulf coasts of Florida. The Northern Gulf coast is especially important as a spawning ground for the Gulf stock. There may even be some sub-populations within the Gulf stock, as tagged fish from the Texas coast were rarely caught going eastward. There also appears to be a group that overwinters in the offshore waters of the Northern Gulf, not making the annual trip to the Keys. My brief summary here regarding seasonal movement is most assuredly an over-simplification and scientists agree more recapture data is needed to understand various Cobia stock movements and boundaries.

Worldwide, the practice of Cobia aquaculture has exploded since the early 2000’s, with China taking the lead on production. Most operations complete their grow-out to market size in ponds or pens in nearshore waters. Due to their incredible growth rate, Cobia are an exceptional candidate for aquaculture. In the wild, fish can reach weights of 17 pounds and lengths of 23 inches in their first year. Aquaculture-raised fish tend to be shorter but heavier, comparatively. The U.S. is currently exploring rules for offshore aquaculture practices and cobia is a prime candidate for establishing this industry domestically.

Spawning takes place in the Northern Gulf from April through September. Male Cobia will reach sexual maturity at an amazing 1-2 years and females within 2-3 years. At maturity, they are able to spawn every 4-6 days throughout the spawning season. This prolific nature supports an average annual commercial harvest in the Gulf and East Florida of around 160,000 pounds. This is dwarfed by the recreational fishery, with 500,000 to 1,000,000 pounds harvested annually from the same region.

One of the Cobia’s unique features is that they are strongly attracted to structure, even if it is mobile. They are known to shadow large rays, sharks, whales, tarpon, and even sea turtles. This habit also makes them vulnerable to being caught around human-made FADs (Fish Aggregating Devices). Most large Cobia tournaments have banned the use of FADs during their events to recapture a more sporting aspect of Cobia fishing.

To wrap this up I’ll briefly recount an exciting, non-fish-catching, Cobia experience. My son and I were in about 35 feet of water off the Wakulla County coastline fishing near an old wreck. Nothing much was happening when I noticed a short fin breaking the water briefly, about 20 yards behind a bobber we had cast out with a dead pinfish under it. I had not seen this before and was unaware of what was about to happen. When the fish ate that bait and came tight on the line the rod luckily hung up on something in the bottom of the boat. As the reel’s drag system screamed, a Cobia that I gauged to be 4-5 feet long jumped clear out of the water about 40 yards from us. Needless to say, by the time we gained control of the rod it was too late; a heartbreaking missed opportunity. Every time we have been fishing since then, I just can’t stop looking for that short, pointed fin slicing towards one of our baits.

by Erik Lovestrand | Dec 3, 2020

Erik works as the UF/IFAS Franklin County Extension Director and as a Regional Specialized Agent for the Florida Sea Grant program in Northwest Florida. His Extension office is located in the historic fishing village of Apalachicola. Due to the small-town, rural nature of Franklin County, he is the only Extension Agent and provides a wide diversity of expertise on topics ranging from home horticulture and gardening to 4-H youth development, natural resources, and invasive species issues.

Growing up in what used to be a rural environment in Central Florida, Erik spent his free time roaming the woods and waters around his home near Apopka. Back then, once school was out for the summer, parents could just turn the kids loose to explore. After receiving his first 5-speed bike, he could be anywhere within a five-mile radius of the house. After high school, Erik worked (not so diligently) to cram a two-year A.A. degree into five years at a local junior college. When he decided to get serious about the future, he moved to Gainesville with his wife Terri and completed a B.S. in Wildlife Ecology in the normal two years; then on to Purdue University for a M.S. in Wildlife.

Coming to work for Extension was the result of a late-career change for Erik but his jobs leading up to this were a great training ground for a well-rounded County Agent. Erik worked for five years after college with the former Florida Game and Fresh Water Fish Commission (GFC now FFWCC) as a regional Education Specialist and then as the statewide Nongame Education Program Coordinator. Then, on to a brief 23-year stint at the Apalachicola National Estuarine Research Reserve as the Education Program Coordinator. This put him in the right place at the right time when the opportunity came to join the UF/IFAS Extension team in the Northwest District. His Extension programs focus on supporting the seafood industry, coastal resource stewardship, and a nice mix of “whatever folks need. The diversity of the job is what keeps it interesting,” says Lovestrand.

Erik teaching about horseshoe crab at Ecology Field Day in Jefferson County.

With their three kids grown and on their own, things have not slowed down much. Terri runs a home day-care and manages a girl’s travel volleyball club. There are four grandkids in the picture now too. Erik enjoys the home garden, spring turkey season and annual hunting adventures on St. Vincent Island. When he retires, he says he will get back to his hobby of making custom knives, something that has gone dormant since he began this job for some odd reason. “I’ve been very fortunate indeed, to have had the career opportunities that bring me to this place,” says Lovestrand. “The NW Extension District is a great place to work!”

by Erik Lovestrand | Sep 25, 2020

Hard work and perseverance are a must for oyster farmers.

On September 17, 2020, President Trump and US Secretary of Agriculture, Sonny Perdue, announced a second phase of an important program assisting America’s farmers. The Coronavirus Food Assistance Program (CFAP 1) was originally announced in April 2020 and now CFAP 2 will provide up to an additional $40 billion in support, along with adding more than 40 specialty crops not previously covered under CFAP 1.

This will be welcome news for many Panhandle farmers; particularly the ones that conduct their “chores” in our Panhandle bays and bayous by producing aquacultured oysters and clams. Losses in sales of molluscan shellfish were not covered under CFAP 1 because they were eligible for some assistance under the CARES Act (Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security). However, many local growers were not able to qualify under the CARES Act for various reasons and are in serious need of assistance. When restaurants and bars were forced to close during the pandemic, sales of fresh oysters and clams basically came to a standstill overnight. Many creative efforts at direct marketing to customers and other avenues to move these time-sensitive products have been undertaken but sales are still far from what they were in 2019, leaving many growers with bills to pay and a significantly reduced bottom line.

Applications for CFAP 2 will be accepted by the USDA from September 21 through December 11, 2020. Payments will be based on 2019 sales, excepting new farmers who had no sales in 2019. Their calculations will be based on 2020 sales up to the point of application. The percent-payment-factor will be figured on a sliding scale, depending on amount of sales; ranging from 10.6% for sales below $50,000 to 8.8% for sales over $1 million.

The USDA has done a very good job of laying out information regarding the program on their website (here) and also provide assistance through their local Farm Service Agency offices around the state. Assistance with applications is available on line at this link. Two of the counties that have a significant and growing oyster aquaculture industry in the mid-Panhandle are Wakulla and Franklin. The FSA office for Wakulla County is in Monticello and can be called at (850) 997-2072 ext 2, or email Melissa Rodgers at melissa.rodgers@usda.gov. Growers in Franklin County can reach their FSA office in Blountstown at (850) 674-8388 ext 2, or email Brent Reitmeier at brent.reitmeier@usda.gov.

Growing oysters in floating bags requires getting wet, alot

With the plethora of confusing acronyms flying around in our present day, CFAP is one worth paying attention to. Why? Because it is providing targeted assistance to a segment of our US economy we should all stand behind. Agriculture is a critical component of all of our lives each and every day. If you have a chance to thank a farmer for what they do, or a legislator for moving this effort forward, or an industry support group that provided the data the legislator needed; don’t miss the opportunity. The hard-working men and woman who produce our food supply, including great, locally grown fresh seafood, deserve it.