by Jennifer Bearden | Nov 8, 2019

Daikon Radish and Buck Forage Oats Plot

When people put in food plots and are not successful, I normally see the following three problems as possible cause. First, they didn’t consider soil pH or fertility. Second, they didn’t choose the right plant varieties for our area. Third, they didn’t manage weeds properly or at all. So following these three steps can help establish a successful food plot.

- Soil pH and fertility

Often wildlife enthusiasts ignore soil pH and fertility. If the soil pH isn’t right, fertilization is a waste of time and money. Different plants have different needs. Some plants need more phosphorus than others. Some need more iron or zinc or copper. The availability of these elements not only depends on whether they are present in the soil but also on the soil pH. Test, Don’t Guess! It takes a week or two to get the full soil sample results back and costs only $10 per sample. That’s a pretty cheap investment to insure a successful food plot.

- Variety selection

Cool season food plots are generally used as attractants for hunters. It does provide some nutrition for the wildlife as well. The goal is to select forages that are desirable to the animals as well as varieties that grow well in our area. Some great choices include: oats, triticale, clovers, daikon radish and Austrian winter peas. We recommend a blend because it extends the length of time that forages are available to the animals as well as decreased risk of food plot failure. For a more information on recommended cool season forages, go to https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/ag139.

Tetra Treat Clover Mixture Plot

- Weed management

Often tilling the food plot prior to planting is enough to manage most weeds. This is okay when you have native weeds on relatively flat land. If erosion is an issue, or if more problematic weeds such as cogongrass are present, a different weed management strategy is recommended. Glyphosate is a good choice as it is a broad spectrum herbicide that will not negatively affect the food plot. Spray the area with glyphosate 3-4 weeks prior to planting to give it time to kill the weeds. Also, remember that many herbicides are not effective during droughts, so you either need to wait until we have rainfall or work with your extension agent to find a solution that will work for your situation.

These three steps are crucial to successful food plots. First, get your soil pH right and then fertilize properly. Next, choose the right forages and varieties to plant. Then control the weeds so they don’t choke out your food plots. The next step is to enjoy this hunting season. For more information on wildlife food plots, you can contact your local county extension agent.

by Jennifer Bearden | Jan 31, 2019

This time of year in Northwest Florida, deer hunters are busy talking about the rut! What’s the rut, you might ask? Simply put, it’s deer breeding season. Deer hunters speculate on peak rut times each year. There are even peak rut forecasts. Why are hunters interested in deer rut? Hunters know that bucks are more active and careless during the rut.

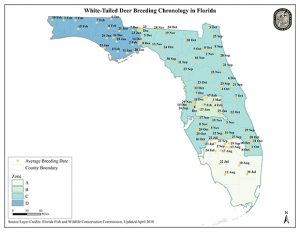

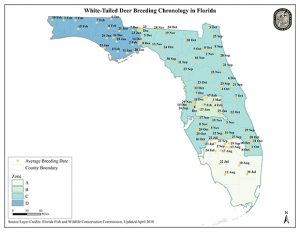

Deer Breeding Chronology in Florida May 2018. Source Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission

Bucks exhibit four rut behaviors: sparring, rubbing, scraping, and chasing. Sparring happens between bucks to establish dominance. This happens during the pre-rut. Dominant bucks are generally the ones who get the does. Bucks also make rubs on trees during the pre-rut period. They start this behavior to remove velvet from their antlers. They continue rubbing to mark their territory with their scent. Scraping is another way they mark their area. A scrape normally occurs under a low hanging branch. The buck will lick or chew on the branch while scraping the ground as well as urinating on the ground. The last rut behavior is chasing does. Does typically won’t be game for this unless they are ready to breed.

In other parts of the country, the rut is long over. Even in other parts of Florida, it is over. Florida has more variability in rut timing than in any other state. In Florida, deer rut starts in July in the southern part of the state and runs through February in the north. Deer breeding dates are more predictable in the northern U.S. where winters are too harsh for fawn survival. Deer breeding in our state is more variable because of our mild winters. Average breeding dates in Northwest Florida are very late compared to other parts of the country and the state. Our average breeding dates generally range from December to mid-February. Gestation takes about 200 days, so this puts fawning dates in late June through early September.

Even though we have average breeding dates for our area, these aren’t “magical dates”. Not all does go into estrus on the same day or even the same week.

8 point buck taken in Northwest Florida in January while chasing a doe. Photo credit: Jennifer Bearden

Estrus only lasts 24 hours and not all does become pregnant during the first estrus period. This means that about 28 days later does go into a second estrus. So the rut period is a range around the average date.

So, to all my fellow hunters in Northwest Florida, enjoy the 2019 rut! I know I have enjoyed watching several bucks chase does as well as having the opportunity to take the biggest buck of my life this January. Good luck to you all in your hunting ventures!

More information about the Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission Deer Breeding Chronology Study can be found at https://myfwc.com/hunting/deer/.

by Jennifer Bearden | Feb 28, 2018

Hog rooting damage in a pitcher plant bog. Photo Credit: Jennifer Bearden

Despite efforts by public and private land managers, feral hog populations continue to rise in many areas in Florida. Feral hogs damage crop fields, lawns, wetlands, and forests. They can negatively impact native species of plants and animals. Their rooting leads to erosion and decreased water quality.

There are several options for controlling feral hogs. Choosing the right option depends on the situation. Options include:

- Hunting with dogs,

- Hunting with guns,

- Box Traps,

- Corral Traps.

Let’s talk about these options.

Hunting with dogs is really not very effective for removing enough hogs to control populations. Dog hunting can move sounders of hogs from areas where damage is occurring for a period of time. This can be helpful when crops need to be protected from hog damage until they can be harvested.

Shooting hogs also is not effective for removing large numbers of hogs. Situations where it is successful include protecting crop fields and for taking hogs that will not go into a trap. Shooting success depends the education level of the hogs and the sophistication of the shooting equipment available. Hogs learn quickly to avoid danger. They learn by watching other hogs who get shot or trapped. Hunting pressure can disrupt hog patterns and make them harder to trap or hunt.

Box traps can be effective at trapping young hogs that are not trap smart. A study conducted by a graduate student, Brian Williams, at Auburn University looked at the efficacy of different trap styles. Young hogs entered box traps and corral traps at similar rates. The study also found that adult females were 120% more likely to enter corral traps than box traps and adult males were more reluctant to enter either trap style but were more likely to enter the corral traps. (Williams et al, 2011)

Corral traps are shown to be most effective for eliminating complete sounders. By eliminating a sounder at once, populations can be reduced. Corral traps are also more economical. In the Auburn study, the trapping cost per pig for box traps was $671.31 and for corral traps was $121.28.

Sounder of hogs in a corral trap. Photo Credit: Jennifer Bearden

Corral traps are best for capturing whole sounders. Box traps can be effective for capturing young hogs. When trap smart adult females or males are in an area, shooting or hunting with dogs are options. Just remember that hunting pressure often just moves the hog problem onto another property. In order to eliminate hogs from a given area, we must employ several of these strategies. For example, we may be able to trap a sounder in a given area but still have a group of boars that will not go into a trap. In this case, we may set up to shoot them after trapping the rest of the hogs in a corral trap. By using these two techniques, we can drastically reduce the number of hogs in an area.

For more information about feral hogs, go to http://articles.extension.org/feral_hogs.

Reference: Brian L. Williams, Robert W. Holtfreter, Stephen S. Ditchkoff, James B. Grand Trap Style Influences Wild Pig Behavior and Trapping Success. Source: Journal of Wildlife Management, 75(2):432-436

by Jennifer Bearden | Feb 27, 2018

Wetland area on Hurlburt Field Air Force Base has been invaded by channeled apple snails. Photo Credit: Lorraine Ketzler

When you think of snails, you probably aren’t thinking about scary monsters that have been unleashed to terrorize us all. I’m here to warn you that you should. The channeled apple snail (Pomacea canaliculata) is a known agricultural pest that competes with native snail species. In our area (panhandle Florida, Hurlburt Field to be exact) this snail is consuming unknown quantities of plant material in our sensitive wetlands. If you didn’t know, Hurlburt Field Air Force Base is one of the last places on Earth where the endangered reticulated flatwoods salamander (Ambystoma bishopi) can still be found, and this endangered salamander relies on healthy wetlands and ephemeral ponds for breeding.

So why should you worry? Just think about how snails eat: snails have a tongue (a radula) with teeth-like structures (denticles) they use to rasp or drill into their food. Normally, nobody would really worry about what snails are eating; they’re snails, right? But, here comes the scary part: when there are many snails, all eating and breeding and growing and eating, they consume a lot of material. And, what once was a cute little snail in your 10-gallon aquarium becomes a rampaging menace when you dump your tank out in the ditch next to your house and the snail escapes into the wild!

Channeled applesnail, Pomacea canaliculata (Lamarck, 1819). Photograph by Jeffrey Lotz, DPI. Click on the picture for more information on apple snails in Florida.

Ok, let’s be honest, it’s not like snails are running wild. I mean, they’re as slow as…well…snails. But what we believe began as a dumped aquarium pet some years ago has become a large population that is expanding into our wetlands. Although it is currently not found in our salamander breeding ponds (whew!), if we don’t do something to stop it, it soon could be. Here we are in Florida, where we have many examples of dumped or escaped animals that are breeding and growing and eating and breeding with no population control. This is one heck of a great example of an invasive species.

So, what are we going to do about this creeping, slimy, menace? Well, in our case, we called our invasive species contractor, and this year we will begin a labor-intensive project to control this species’ population on Hurlburt Field. We could use your support! Please use the IveGot1 app or EDDMaps to report local encounters with channeled apple snails. And, please DO NOT release non-native wildlife into the wild!

Guest Author:

Lorraine “Rain” Ketzler

Associate Wildlife Biologist

Hurlburt Field Natural Resources Manager

by Jennifer Bearden | Feb 27, 2018

Fluffy Mimosa Bloom. Photo Credit: Mary Salinas

All along the roadsides and in home landscapes in summer, a profusion of fluffy pink blossoms are adorning trees known as mimosa, or Albizia julibrissin. This native of China was introduced to home landscapes in this country in the 1700’s to enjoy the fragrant, showy flowers and fine, lacy foliage. However, there is a dark side to this lovely tree. After blooming, it produces an abundance of pods each containing 5 to 10 seeds. Seeds can be spread by wildlife and water; this is evidenced by the appearance of mimosa trees along the roadways, streams and in our natural areas. The seeds can also remain dormant for many years, allowing the trees to keep sprouting long after the mother tree is gone.

Mimosa has been categorized as an invasive exotic plant in Florida by the University of Florida IFAS Assessment of Non-Native Plants in Florida’s Natural Areas. This designation means that the tree has not only naturalized, but is expanding on its own in Florida native plant communities. This expansion means that our native plants in natural areas get crowded out by mimosa as it reproduces so prolifically.

Mimosa tree in bloom. Photo Credit: Mary Salinas

The Florida Exotic Pest Plant Council (FLEPPC) publishes a list of non-native plants that have been determined to be invasive. Click here for the most recent 2017 list!

The first step in controlling this pest plant is to remove existing plants in the landscape. Cutting it down at soil level and immediately painting the stump with a 25% solution of glyphosate or triclopyr should do the trick. Further details and control methods can be found here.

There are some native trees that make excellent alternatives to mimosa such as fringe tree (Chionanthus virginicus), silverbell (Halesia carolina) and flowering dogwood (Cornus florida).

Guest Author:

Mary Salinas

Residential Horticulture Agent

Santa Rosa County