by Judy Biss | Mar 12, 2016

The Beekeeping in the Panhandle Working Group is pleased to offer the 5th Annual Beekeepers Field Day And Trade Show 2016 Beekeeping is one of the fastest growing hobby and commercial endeavors in Florida. There is much to learn and share about this fascinating trade.

The Beekeeping in the Panhandle Working Group is pleased to offer the 5th Annual Beekeepers Field Day And Trade Show 2016 Beekeeping is one of the fastest growing hobby and commercial endeavors in Florida. There is much to learn and share about this fascinating trade.

The workshop and trade show offers something for every level and interest, and this year’s event features:

- Extended Opportunities for Hands-On Open Hive Experiences

- Presentations on the Latest in Research-Based Beekeeping Management Practices

- Interaction With Expert Beekeepers

- Vendors with Beekeeping Equipment and Hive Products

- Door Prizes Include a Grand Prize Each Day of a 10-Frame Bee Hive!

Dates:

Friday April 1, 2016 and Saturday April 2, 2016

Place:

UF/IFAS Extension Washington County Office,

1424 Jackson Avenue, Chipley, FL 32428

850-638-6180

Time:

8:00 am – 5:00 pm each day

Registration:

Includes Lunch, Refreshments, Door Prize Tickets, & Educational Sessions

-

$25 for One Day or $40 for Both Days per Person

-

$10 Age 12 and Under Each Day

-

Late Fee of $10.00 after March 22nd.

Two ways to register:

For More Information Contact:

- UF/IFAS Extension Washington County at 850-638-6180

- UF/IFAS Extension Calhoun County at 850-674-8323

Download the printable flyer with agenda & details:

by Judy Biss | Dec 4, 2015

To be successful hunters of the night, owls have some truly amazing physiological adaptations. This closeup of a barn owl shows a few in the large eyes and dish shaped face that help perfect its hearing and sight. Compliments UF/IFAS File Photo

Some of my favorite creatures are owls, and as you can see by the quotes below, owls have captivated humans across the ages.

And thorns shall come up in her palaces, nettles and brambles in the fortresses thereof: and it shall be an habitation of dragons, and a court for owls.

Isaiah 34:13

“Owl,” said Rabbit shortly, “you and I have brains. The others have fluff. If there is any thinking to be done in this Forest–and when I say thinking I mean thinking–you and I must do it.”

― A.A. Milne, The House at Pooh Corner

“I think I’m a tiny bit like Harry ‘cos I’d like to have an owl. Yeah, that’s the tiny bit, actually.”

― Daniel Radcliffe (Actor who portrays Harry Potter)

According to the Florida Audubon Society, Florida is the year-round home to six (6) species of owls and four (4*) occasional visitors such as the striking Snowy Owl. These owls are listed in the Audubon of Florida Checklist of Florida Birds and are the:

Barn Owl

Barred Owl

Burrowing Owl

Eastern Screech-Owl

Great Horned Owl

Short-eared Owl

(*exceedingly rare)

Flammulated Owl *

Long-eared Owl *

Northern Saw-whet Owl *

Snowy Owl *

Each of the species links above will take you to the Cornell University CornellLab of Ornithology providing information about these owls including an audio clip of their unique calls. It’s an informative site, so be sure to click on your favorite owl for more information and to listen to their calls.

Owls are mainly nocturnal hunters, which means they are most actively feeding at night. Depending on the species, their diet is quite varied and includes, insects, lizards, a variety of small rodents, birds, and even crayfish. Nesting pairs of owls and their voracious owlets can consume thousands of small rodents in a year. Because they eat a variety of prey and are significant rodent predators, owls are welcome residents on most farms and homesteads.

To be successful hunters of the night, owls have some truly amazing physiological adaptations, such as the ability to rotate their heads 270 degrees, ears that are offset on the sides of their head in order to pinpoint location of prey, the ability to control feathers on their dish shaped face to direct sounds into their ears, and comb like structures on their feathers to silence them in flight. The following details about these and other adaptations are taken from the Cornell University CornellLab of Ornithology – the Owl Page, and Blogs at Cornell University-Anatomy of Owls.

Sight

Owls’ large forward facing eyes give them the best stereoscopic vision of all birds, which is vital for judging distances. The shape of their eyes, their unusually high number of light-sensitive cells, their large pupils, and a reflective layer behind the retina (called the “tapetum lucidum”) give them excellent nocturnal vision useful when hunting at night or navigating dark forests. The shape of their eyes limits their ability to move them in the eye sockets, but their necks can turn up to 270 degrees.

Hearing

Their ability to locate prey by sound alone is the most accurate of any animal that has ever been tested. These owls can catch mice in complete darkness in the lab, or prey hidden by vegetation or snow out in the real world. Their ears are placed unevenly on their head and point in slightly different directions, giving the ability to hear where a sound is coming from without moving their heads. Owls can also funnel sound toward their ears by manipulating different types of feathers around the ears and face.

Silent Flight

On both the primary and secondary feathers, there are comb-like structures at the edge of the feather that are responsible for muffling the sound of the air going over the wing – this essentially makes an owl silent when they fly. Also, an owl’s feathers can separate from each other on the same wing; therefore, the air flows over each of the individual feathers and their comb-like structures, which maximizes how silently an owl flies.

BELLE GLADE—University of Florida graduate researcher Cosandra Hochreiter checks on a barn owl nesting site on the grounds of UF’s Everglades Research and Education Center. The five owlets in this corner were among several babies and their parents nesting in this abandoned barn at the research center. Researchers are trying to boost the population of barn owls in the Everglades Agricultural Area because they are a natural form of rodent control. Rodents can cause up to $30 million damage per year to sugar cane and vegetable crops, and a nesting pair of barn owls can eat almost 3,000 rodents over the course of a year. Compliments UF/IFAS File Photo

Owl Pellets

Owls swallow their prey whole or in large pieces, but they cannot digest fur, teeth, bones, or feathers. Like other birds, owls have two chambers in their stomachs. In the first chamber, all the digestible parts of an owl’s meal are liquefied. Then the meal passes into the second chamber, the muscular stomach or gizzard, which grinds down hard structures and squeezes the digestible food into the intestines. The remaining, indigestible fur, bones, and teeth are compacted into a pellet which the owl spits out. Owls typically cast one pellet per day, often from the same roosting spot, so you may find large numbers of owl pellets on the ground in a single place.

Nesting

Owls will typically nest in cavities of mature trees, or will use the nests of other birds or even squirrels. Burrowing Owls nest in the ground, and although it can dig its own burrow, it often uses holes already created by skunks, armadillos, or tortoises. Some owls will use artificial nest boxes, and building plans for the Great horned, Barred, and Barn owls are found here at this website: Cornell University CornellLab of Ornithology – the Owl Page

So, the next time you are enchanted by the familiar sound of our common Barred Owl, or if you happen to find a few owl pellets below a tree, think also of the many amazing attributes of Florida’s owls, our stealthy nocturnal predator.

For more information on this topic please see the following resources used for this article:

Barn Owl (Tyto alba)

Barred Owl (Strix varia)

Helping Cavity-nesters in Florida

Cornell University CornellLab of Ornithology – the Owl Page

Florida Audubon Society

North American Owls: Biology and Natural History

by Judy Biss | Jul 18, 2015

Woodlands and rangelands are important to both our economy and environment. Photo by Judy Ludlow

Most of us living in panhandle Florida recognize that our farmers and ranchers are committed to sustainable production of food, fiber, and fuel for generations to come, but how will farmers continue to be productive while sharing natural resources with an ever growing population and an intricate environment? How will Florida’s agricultural lands, rangelands, and woodlands continue to contribute to the quality of our environment and to our economy?

Florida Rangelands:

According to the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service “Range and pasture lands are diverse types of land where the primary vegetation produced is herbaceous plants and shrubs. These lands provide forage for beef cattle….and other types of domestic livestock. Also many species of wildlife…depend on these lands for food and cover.” Florida’s rangelands and woodlands are a significant component of Florida’s agricultural industry.

According to the 2012 Census of Agriculture there were:

- 3,749,647 acres of permanent pasture and rangeland in Florida

- 1,368,171 acres of pastured woodland in Florida

Benefits of Rangelands:

Florida’s 5.1 million acres of agricultural rangelands and woodlands not only support the economy, but abundant wildlife too. These well managed lands are living systems sustaining livestock, wildlife, and healthy soils. Benefits of these lands include important economic and ecological services like reducing our carbon footprint, increasing water conservation, providing forage for livestock, habitat for wildlife and game, preservation of cultural heritage, and sustainable timber. Additionally, hunting, fishing, and wildlife viewing is a multi-billion dollar industry within which Florida’s rangelands play a significant role. Florida’s rangelands are also important for the continued survival of many threatened species like the Crested Caracara, Snail Kite, Gopher Tortoise, Florida Scrub-Jay, Eastern Indigo Snake, Roseate Spoonbill, Wood Stork, and Sandhill Cranes.

Gopher Tortoise. Photo by Chuck Bargeron, University of Georgia, Bugwood.org

Sandhill Cranes in a North Florida pasture. UF/IFAS Photo by Josh Wickham.

Challenges to Florida’s Rangelands:

Threats to Florida rangelands include conversion into urban areas and fragmentation of large tracts of lands causing disconnection from other farmlands and natural areas. Contiguous, connected “wildlife corridors,” are important for many species of wildlife. Additionally, the establishment of non-native, invasive animals and plants; and alterations of natural and necessary processes such as fire, floods, and droughts, can disrupt the full economic and environmental potential of these lands.

Agricultural Best Management Practices and Education:

Today’s farmers use best management practices (BMPs) relying on up-to-date technologies and research to protect Florida’s unique natural resources, especially our precious water, while at the same time maximizing their production. BMPs are based on University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (UF/IFAS) research and are practical, cost-effective actions that agricultural producers can take to conserve water and reduce the amount of pesticides, fertilizers, animal waste, and other pollutants entering our water supply. They are designed to benefit water quality and water conservation while maintaining or even enhancing agricultural production. According to the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, for example, agricultural producers save 11 billion gallons of water each year by their conservation practices.

Many of Florida’s rangeland and woodland owners also take advantage of educational programs available to them such as the UF/IFAS Forest Stewardship Program. The mission of this multi-agency program is to help and encourage private landowners to manage their lands for long-term environmental, economic, and social benefits. According to their annual report: “In 2014 the Program reached 503 landowners and professionals directly with workshops and field tours. These landowners and professionals collectively own and/or manage over 2 million acres across Florida.”

Summary and Additional Resources:

Florida’s agriculture producers are deeply committed to being stewards of their lands and our surrounding environment. Their adoption and support of best management practices as well as continuing education is critical for sustainable production and also for feeding the world of the future.

For more information on this topic please see the following resources:

UF/IFAS Forest Stewardship Program

UF/IFAS Extension – Range Cattle Research and Education Center

UF/IFAS Extension – Best Management Practices

Florida Farm Bureau’s County Alliance for Responsible Environmental Stewardship Program (This Farm CARES)

Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services – Best Management Practices

The Nature Conservancy – Florida Ranchlands

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations – Grasslands and Rangelands

USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service

by Judy Biss | Mar 27, 2015

Freshwater Jellyfish, Craspedacusta sowerbyi, Lankester, 1880. Photo Credit: U.S. Geological Survey Archive, U.S. Geological Survey, Bugwood.org

Yes, you read the title correctly, it says freshwater jellyfish in Florida! The first time I encountered these unusual aquatic creatures was while swimming in a small lake in southern Indiana. It turns out these jellyfish, while not very common, have been found in almost every state in the U.S. This jellyfish is known as a hydrozoan, a tiny aquatic invertebrate animal. It grows into a few different forms during its life-cycle and is most easily identified when it takes the form of the small jellyfish. This form during its life-cycle is known as a hydromedusa and measures up to about 25 mm in diameter, which is a little larger than a penny.

The scientific name for this unusual organism is Craspedacusta sowerbyi and it is native to the Yangtze River valley in China. It was first described to science in 1880 from specimens collected in water lily tanks in London. This freshwater jelly is now common in temperate climates almost worldwide, and was most likely introduced into the US attached to ornamental aquatic plants and fish.

Hydromedusae, the form that looks like a jellyfish, are produced only sporadically from their otherwise immobile attached form known as a polyp on lake and river bottoms. Sightings of the jellyfish are most common in summer and fall but may go several years between occurrences. The freshwater jellyfish mainly eats tiny aquatic zooplankton, catching them with their stinging tentacles. They are not considered dangerous to humans.

The impact this non-native freshwater jellyfish may have on aquatic ecosystems is not well known. Sightings of this organism are being recorded by the U.S. Geological Survey Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Information Resource and EDDMapS (a web-based mapping system for documenting invasive species distribution, launched by the Center for Invasive Species and Ecosystem Health.)

Based on data from these resources, the freshwater jellyfish, Craspedacusta sowerbyi, has been found in the following north Florida counties: Escambia, Walton, and Washington counties, and in the following peninsula Florida counties: Lake, Hernando, Highlands, Orange, Miami-Dade, Pasco, and Putnam.

So, while you’re enjoying your favorite freshwater swimming hole this summer, keep a sharp eye out for these harmless, fascinating, yet non-native, jellyfish! If you find them, report your sightings here at EDDMaps.

Information from the following resources were used to write this article:

by Judy Biss | Oct 10, 2014

Longleaf pine’s desirable characteristics have motivated restoration efforts on timber-lands, agricultural lands, private lands, and public lands. Photo by Judy Ludlow

Steeped in history, the majestic longleaf (Pinus palustris) is an economically and ecologically important tree species of the Atlantic and Gulf coastal plains. Its species name “palustris” means “of the marsh,” and although it is commonly associated with sandy, well drained areas, the longleaf pine is adapted to a range of soil types. Once the dominant tree on 60 million acres in the S.E. United States, development and intense harvesting have reduced its current range to about 3 million acres. The longleaf’s desirable characteristics, however, have motivated restoration efforts of this pine tree on timber-lands, agricultural lands, private lands, and public lands. Longleaf’s desirable characteristics include being a native, well-adapted, ecologically, and economically valuable tree.

[important]Longleaf pine takes 100 to 150 years to reach their full size of 100-120 feet, and can live to 300 years old![/important]

The longleaf pine is important because they are native and well-adapted:

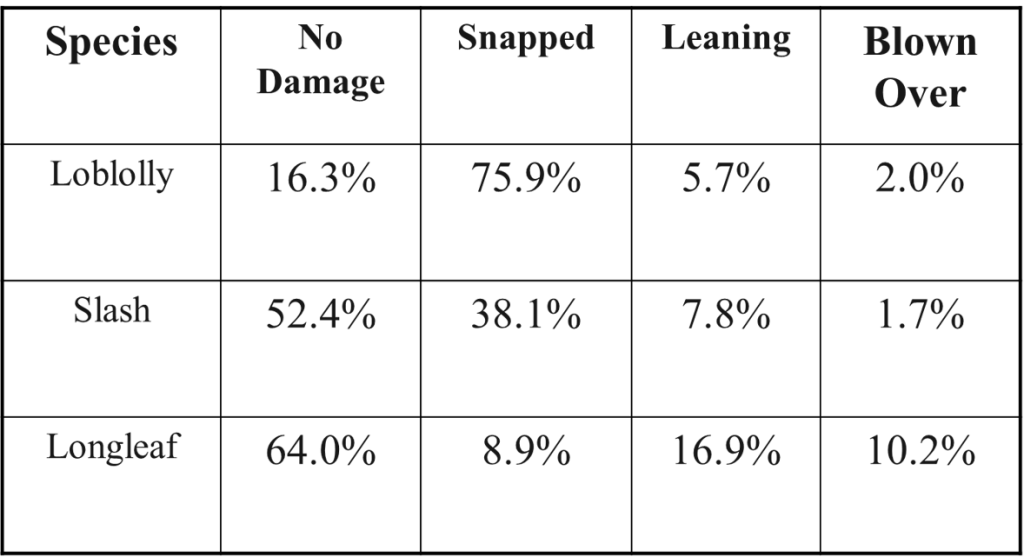

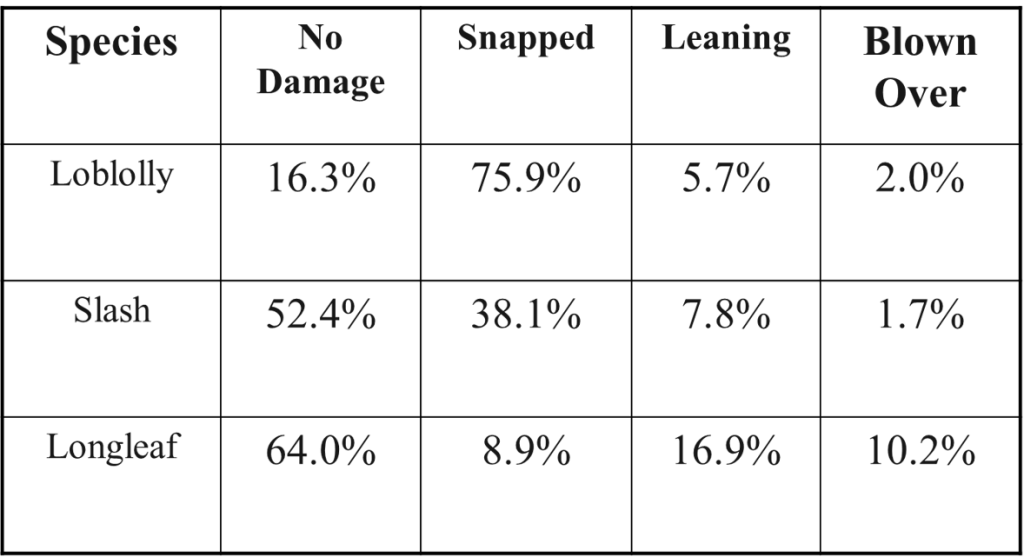

The more widely adapted a natural commodity such as the longleaf pine tree species is, the safer an investment in the future it becomes. Because the longleaf is native and adapted, it is highly resistant to most diseases and insects such as the Southern Pine Beetle and Fusiform rust. It is ideally suited to, and in fact, dependent upon, a high-frequency (every 5 to 10 years), low-severity surface fire regime. Its seed will germinate on the mineral soil exposed by fire. Fire also controls the understory vegetation that would otherwise compete with longleaf preventing it from reaching its maximum growth potential. The established longleaf is also quite wind resistant in comparison to other southern pines. See table 1 below.

Table 1. Hurricane Katrina Impacts by Species. Data Courtesy of The Longleaf Alliance and Glen Hughes

The seedling grass-stage of longleaf is uniquely resistant to fire, and this characteristic is critical as the grass stage of longleaf can last for 1-5 years while the tree is forming its strong root system underground. The terminal bud of the grass stage is protected by a moist, dense, tuft of needles. As the tuft burns towards the bud from the needle tips, water is vaporized. The steam reflects heat away from the bud and extinguishes the fire. The bud also has scales for protection and a silver fuzzy covering that probably also reflects heat. (US Forest Service)

Longleaf pine provides economic benefits through its high quality timber and non-timber products:

Longleaf pine provides economic benefits through its high quality timber and non-timber products:

Planting longleaf as an investment is a long-term prospect, and its financial viability and profitability becomes more apparent over time. It is recommended for thinning 4 times – from 20 to 45 years of age. The thinned trees themselves will provide income, while leaving the remaining trees to mature to their most valuable state. The remaining trees also act as “shelterwood” for subsequent stands. This “shelterwood” protects young seedlings. In a well-managed longleaf pine stand, future trees can be established using natural regeneration and fire, virtually eliminating repeated planting and site prep expenses. Longleaf pine produces high value timber with clear, straight wood and few defects. It was used extensively in the past for ship building, in fact, records indicate that some of the choicest stands of longleaf were set aside by the English Crown for the exclusive use of the British Navy! This pine yields a higher percentage of valuable poles than any other southern pine, and on average, poles are worth about 50% more per ton than saw-timber.

Percent poles at 39 years old:

- Loblolly – 8%

- Slash – 12%

- Longleaf – 72%

Longleaf also produces valuable non-timber products such as pine straw. Longleaf pine straw is generally more desirable than other straw and commands a higher retail value. As the longleaf stand matures, more pine straw can be harvested.

Pine Straw Yields:

Age 6 – low yields

Age 10 – higher yields

- between 125 to 200 bales per acre

Age 15 – maximum yield

- 200 to 300 bales per acre

[important]Because of the positive economic and ecological traits of the longleaf pine, there are financial assistance programs available to offset the cost of tree establishment. Please refer to the links at the end of this article for more information.[/important]

Because of the positive economic and ecological traits of the longleaf pine, there are financial assistance programs available to offset the cost of tree establishment. Photo by Judy Ludlow

Longleaf pine are ecologically important:

It is now recognized that a properly managed longleaf pine stand is one of the most biologically diverse habitats in North America! A wide variety of wildlife depends on the longleaf pine ecosystem. Endangered species such as red-cockaded woodpeckers and indigo snakes are threatened by the loss of longleaf pine habitat. The seeds are an excellent food source for many species. Gopher tortoises, Florida mice, gopher frogs, and eastern diamond-back rattlesnakes are among the native animals in the ecosystem.

Proper management provides optimal conditions for longleaf and associated understory plants to thrive. Photo by Judy Ludlow

Longleaf pine are embedded in our aesthetic and cultural history:

Mature longleaf forests are a uniquely beautiful sight to see. The open, park-like, vistas are visually stunning with spring and fall wildflowers. These were the southern pine forests that early settlers and pioneering botanists explored. They provided turpentine, pitch, grazing lands, valuable timber, and wildlife habitat that supported the development of the southeastern United States. No wonder there is a growing interest among landowners and state and federal agencies to reestablish this important and outstanding tree ecosystem.

For more information about the Longleaf Pine, please see the following resources used for this article:

Longleaf Pine Initiative-Cost Share Program

Conservation Reserve Program Longleaf Pine Initiative-Cost Share Program

Longleaf Pine Private Landowner Incentive Program-Cost Share Program

Longleaf Pine – USDA Forest Service

UF/IFAS Florida Forest Stewardship

The Longleaf Alliance

Longleaf Pine Regeneration

Opportunities for Uneven-Aged Management in Second Growth Longleaf Pine Stands in Florida

Pinus palustris: Longleaf Pine

The Beekeeping in the Panhandle Working Group is pleased to offer the 5th Annual Beekeepers Field Day And Trade Show 2016 Beekeeping is one of the fastest growing hobby and commercial endeavors in Florida. There is much to learn and share about this fascinating trade.

The Beekeeping in the Panhandle Working Group is pleased to offer the 5th Annual Beekeepers Field Day And Trade Show 2016 Beekeeping is one of the fastest growing hobby and commercial endeavors in Florida. There is much to learn and share about this fascinating trade.