by Rick O'Connor | Jun 21, 2024

Many from the “baby boomer” generation, which includes me, can probably tell you weather patterns have changed since we were kids. Growing up in Pensacola I remember the pattern of a typical summer day. It would be sunny in the morning, when most of us would get out and do our daily activities, whatever those might have been. The land breezes would shift to sea breeze around noon and by mid afternoon there would be a thunderstorm. These storms generally passed quickly and were followed by a sunny, but cooler afternoon with wonderful sunsets. Most summer days were like this. During winter we generally had frost on the ground – at least three days a week. Again, those who grew up with this I am sure have noticed – it has changed.

In the past people would enjoy the beach in the mornings before the daily afternoon thunderstorm.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Our summer days now seem to be periods of several long hot days with little or no rain at all. When rain does come it seems to be intense, it could last all day and may occur for several days in a row. We will go through periods of intense rain followed by days of all most drought conditions. The days seem to be hotter. If you watch the news, we are continually breaking temperature records. The same could be said about rainy days, there have been several “100-year flood” events in the past decade. Hurricanes were once things we dealt with once in a decade, we now seem to be in the “cone of uncertainty” of some storm each season.

In addition to the changes with weather have come changes with coastal plants and animals. Mangroves, snook, and bone fish – all once thought of as “south Florida species” are now appearing along the Florida panhandle. Manatee encounters are increasing and the threat of invasive species – which once was not an issue due to our colder winters – is something we now must look at. It is changing. As we observe these changes, I often get the question – “is this due to climate change?”

Black mangroves growing near St. George Island in Franklin County.

Photo: Joshua Hodson.

In the 1990s I taught environmental science at Pensacola State College and AP Environmental Science at Washington High School. Climate change was a topic we covered and discussed the latest science behind the topic. I still have the textbook I taught from and thought it might be interesting to look back at what was being said at the time and whether the predictions given were actually happening. The chapter on climate change began with a case study. It provided the following:

In June of 1991 the active volcano Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines erupted. The eruption released ash and compounds 22 miles up into the atmosphere. Hot gases and ash rolled down the mountain side killing hundreds of people and filling valleys with toxic materials. It destroyed communities and caused hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of damage. Despite the horrific impact it also provided scientists with an opportunity.

The eruption of Mt. Pinatubo.

Photo: NOAA

Climate scientists had been monitoring global warming for a couple of decades at that point and had developed computer models that could predict both the change of climate in the future (if such warming trends continued) and what impacts these changes may have. But unlike the computer models used to predict the course and landfalls of hurricanes, they had no way of testing them. But with the eruption of Mt. Pinatubo, the opportunity was there.

Based on such models, James Hansen, a NASA scientist at the time, predicted the volcanic eruption would first cool the planet 1°F over a 19-month period and then begin to warm. He predicted that by 1995 temperatures would return to normal. His predictions proved correct. The model had passed the test. This case helped convince most scientists and policy makers that climate model projections should be taken seriously.

Hansen’s model, and 18 other climate models, indicated that global temperatures were likely to rise several degrees during the century – mostly due to human actions – and affect global and regional climates and economies.

Over the next few weeks, we will post a series of articles looking at what was discussed decades ago and see whether the weather patterns we are experiencing match the predictions we discussed in class at that time. We will take another look at climate change.

Part 2 – How Might the Earth’s Temperature and Climate Change in the Future?

by Rick O'Connor | Jun 7, 2024

Northwest Florida Regional Lionfish Workshop Notes

Feb 8, 2024 – Ft. Walton Beach, Florida

Lionfish first appeared in the northern Gulf of Mexico in 2010. At that time, it was a huge concern – and still is – but it got the public’s attention. Fishermen were concerned that lionfish would deplete targeted species they enjoyed catching and made money from. The number of lionfish divers were encountering was staggering and videos showed reefs that were basically covered with them, and few other species around.

The Invasive Lionfish

The community reacted by initiating a few local tournaments with awards and prizes and there was a push to harvest them commercially as a food product – lionfish are very good to eat. In 2013 the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission and Florida Sea Grant held its first regional workshop to discuss the state of the lionfish invasion in our area and how management efforts were going. It was reported at the time that lionfish densities off the Pensacola area were among the highest in the South Atlantic region. They seemed to have a preference for artificial reefs over natural ones and there were studies suggesting how frequently lionfish removal efforts were needed in order to decrease their population. Studies showed that on reefs where lionfish were abundant, red snapper stayed farther away and further up in the water column. There were several talks on the general biology of the creature – which was still unknown to much of the public.

The Lionfish Removal and Awareness Day Event in 2017.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

In 2019 the 2nd regional workshop occurred. The densities of lionfish had declined – possibly due to the commercial and recreational harvest efforts as well as the lionfish tournaments that were occurring. It was at this time that divers began to notice skin lesions on some of the fish and there were questions as to what was causing this and whether it had an impact on their populations. The commercial harvesting had not gone as well as expected primarily due to pricing issues, but education/outreach efforts had made a big impact – almost everyone knew about lionfish and the problems they were causing. Some on the commercial harvest side of the issue had turned to taking visiting divers out to hunt lionfish. For many this was a more lucrative venture than harvest and selling. But people still wanted to eat lionfish and finding local places that served was not easy.

Skin ulcers have been found on many lionfish in the region.

Photo: Alex Fogg

The 3rd Regional Lionfish Workshop was scheduled for 2024 and occurred in February in Ft. Walton Beach. 52 attended to hear presentations on the latest research, commercial harvest, tournaments, and education/outreach efforts. Here are some highlights from those presentations.

Research Updates

- The high densities in 2013 had declined by 2019 but there was no update on current densities of lionfish. Anecdotal evidence from divers suggested that they may be increasing again.

- The source of the skin lesions was still unknown, but some evidence suggested that it could have contributed to the decline of lionfish between 2013-2019. The lesions are still occurring in lionfish.

- eDNA studies by the University of West Florida found lionfish eDNA in samples collected from the upper portions of local estuaries – suggesting they may have entered the bay. The research team also found lionfish eDNA in the feces of some shorebirds nesting in the area. This triggered more questions than answers.

- PCB monitoring in fish tissue obtained from the USS Oriskany as part of the artificial reef permit. The initial target species for this study have declined on the wreck – or at least at not as frequently harvested as the study required. However, lionfish have increased on the reef and are now being used to continue this monitoring project.

Commercial Harvest Updates

- Florida Sea Grant presented results of a regional survey of seafood buyers and restaurants. Few were selling lionfish. Concerns included size and yield from processing, adequate supply, and the fact they were venomous. However, almost all of them were interested in selling lionfish and were willing to learn how to navigate these barriers to make it happen.

Tournament Updates

- The FWC Lionfish Challenge is still going strong, and they plan to continue to support it.

- The Emerald Coast Open is still the largest lionfish tournament in the country. This year they harvested over 18,000 lionfish.

- Overall, across the region and state, lionfish tournaments were on the decline.

- International tournaments reported mixed results – some doing well, some not so well. Those doing well were doing very well.

- A new tournament was kicking off in Pensacola during the fall season – the Pensacola Lionfish Shootout.

Education and Outreach Updates

- Citizen science programs are increasing.

- Many school programs have included lionfish topics within their lesson plans.

Some questions remain unanswered currently.

- Have the densities of lionfish increased or decreased since 2019?

- What is the cause of the skin lesions found on some lionfish?

- Are lionfish inhabiting parts of our estuaries?

- Can we get lionfish on more menus in the region?

The next regional workshop is scheduled for 2029. Until then, many will be involved in trying to answer these questions and manage this problem. If you have any questions concerning the current state of lionfish in our area, please contact your county extension office.

by Rick O'Connor | May 17, 2024

Recently I participated in a local festival to educate the public about the Rice’s Whale – the newly described species in the Gulf of Mexico that is now listed as critically endangered, possibly the most endangered whale in the world’s oceans. I honestly did not know enough about it to provide much education and chose to do terrapin conservation at my table instead (something I know more about) but have since learned much about this new member of the Gulf community.

One of the more frequent comments I heard during the event was “I did not know we even had whales in the Gulf”. This is understandable since we rarely see them – most of us have never seen one. When we think of whales we think of colder climates like Alaska, New England, and the colder waters off California. But many large whales must give birth to their smaller calves in warmer waters – so, they make the trek to tropical locations like Hawaii and Florida to do so. But there are also resident whales in the tropical seas.

You first must understand that the term “whale” does not only mean the large creatures of whale hunting fame, but any member of the mammalian order Cetacea. Cetaceans include both the large baleen whales – like the blue, gray, and right whales – but also the toothed whales – like the sperm, orca, and even the dolphins.

The Right whale is another critically endangered whale found in the Gulf of Mexico. Image: NOAA.

There are 28 cetaceans that have been reported from the Gulf, 21 of those routinely inhabit here. Most exist at and beyond the continental shelf – hence we do not see them. Only two frequent the waters over the shelf – the Atlantic Bottlenose Dolphin and the Atlantic Spotted Dolphin, and only one is routinely seen near shore – the Atlantic Bottlenose Dolphin.

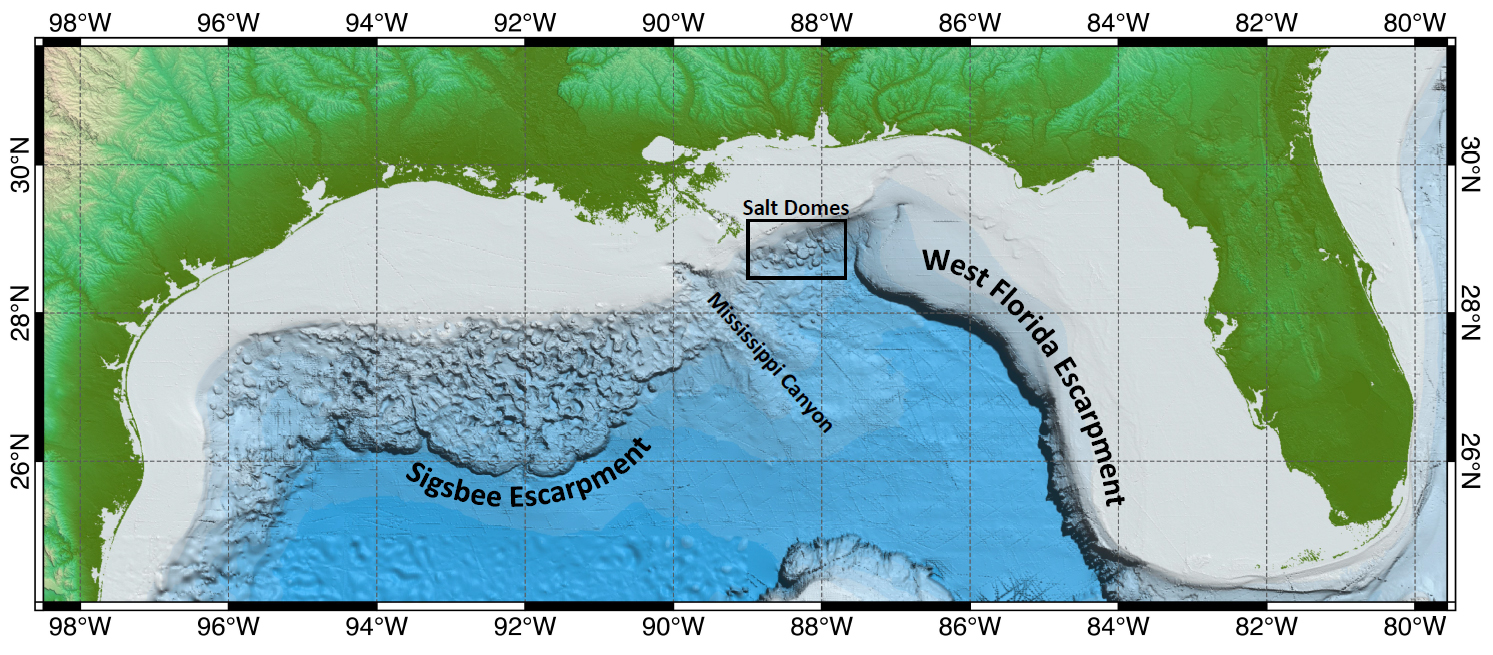

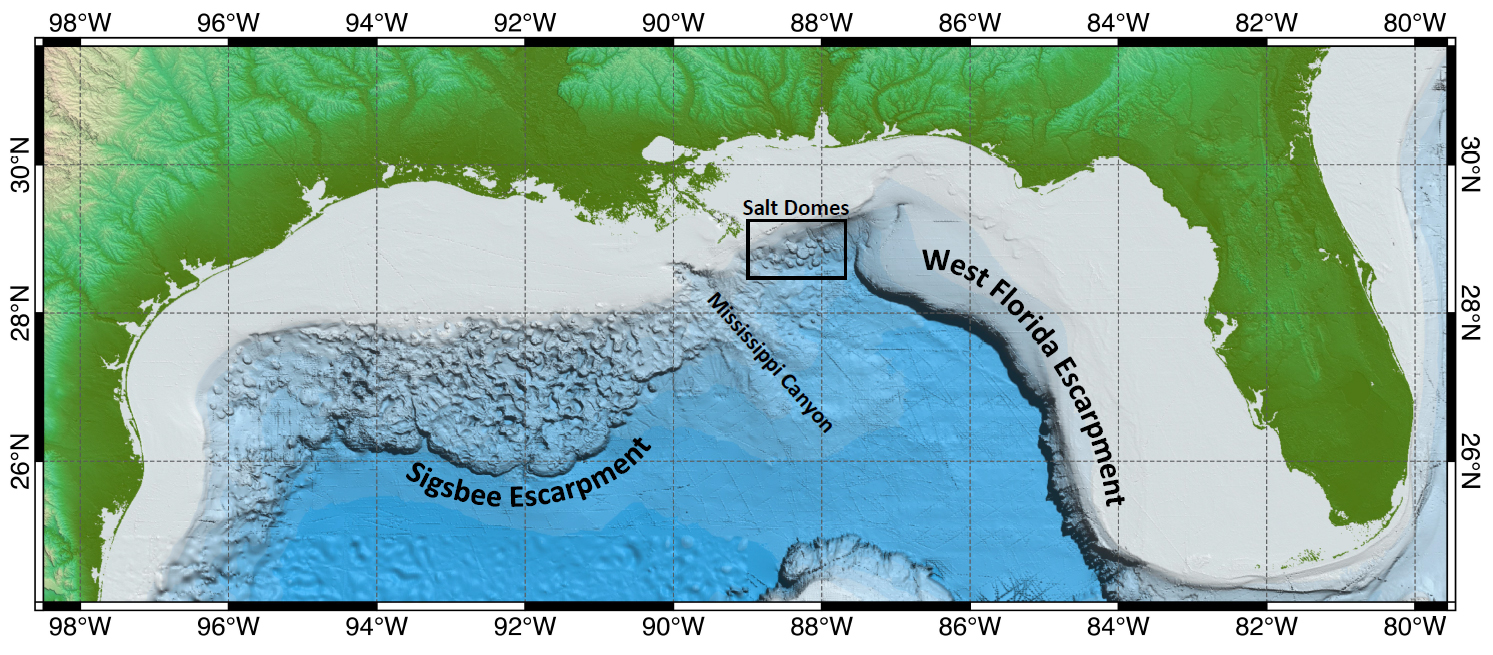

This image shows the location of the continental shelf and thus the location of most of the whales found in the Gulf of Mexico. Image: NOAA.

But offshore, out at the edge of the continental shelf, exists several species of large and small cetaceans. The endangered Sperm, Sei, Fin, Blue, Humpback, and Northern Right whales have been seen. Of those only sperm whales are common. Others include several beaked whales (which resemble dolphins but are much larger), large pods of other species of dolphins, pygmy and dwarf sperm whales, pygmy and false killer whales (as well as the killer whale itself), and other baleen whales such as the Minke and Bryde’s whale.

The Bryde’s whale is one of interest to this story.

The Bryde’s whale (pronounced “brood-duss” – Balaenoptera edeni) is a medium sized baleen whale, reaching lengths of about 50 feet and weighing 30 tons. It is often confused with the larger sei whale. They are found in tropical oceans across the planet and are not thought to make the large migrations of many whales due to the fact it is already here in the tropics for birth, and its food source is here as well. They reside in the northeastern Gulf of Mexico extending from the DeSoto Canyon, off the coast of Pensacola, to the shelf edge near Tampa. They appear to travel alone or in small groups of 2-5 animals. They feed on small schooling fish, such as pilchards, anchovies, sardines, and herring. Their reproductive cycle in the Gulf is not well understood.

The Bryde’s whale was thought to be the only resident baleen whale in the Gulf of Mexico. Photo: NOAA.

Strandings have occurred – as of 2009, 33 have been logged. There are no records of mortality due to commercial fishing line entanglement, but vessel strikes have occurred. Due to their large population across the planet, they were not considered for listing under the Endangered Species Act, but that may change in the Gulf region due to human caused mortality. Between 2006-2010 it was estimated that 0.2 Bryde’s whales died annually due the vessel strikes.

In the 1960s Dr. Dale Rice described the Gulf of Mexico population as a possible subspecies. It is the only baleen whale that regularly inhabits the Gulf of Mexico. And ever since that time scientists examining stranded animals thought they may be dealing with a different species.

In the 1990s Dr. Keith Mullin began examining skull differentiation and genetic uniqueness from stranded animals of the Gulf population. Dr. Patricia Rosel and Lynsey Wilcox picked up the torch in 2008. In 2009 a stranded whale, that had died from a vessel strike, was found in Tampa Bay and provided Dr. Rosel more information. In 2019 a stranded whale, that had died from hard plastic in gut in the Everglades, was examined by Dr. Rosel and her team and, with data from this skull, along with past data, determined that it was in fact a different species. The new designation became official in 2019.

The newly described Rice’s whale only exists in the Gulf of Mexico. Photo: NOAA.

The new whale was named the Rice’s whale (Balaenoptera ricei) after Dr. Dale Rice who had first describe it as a subspecies in the 1960s. With this new designation everything changed for this whale. This new species only lives in the Gulf of Mexico, and it was believed there were only about 50 individuals left. Being a marine mammal, it was already protected by the Marine Mammal Protection Act, but with this small population it was listed as critically endangered and protected by the Endangered Species Act.

New reviews and publications began to come out about the biology and ecology of this new whale. Rice’s whales do exist alone or in small groups and currently move between the 100m and 400m depth line along the continental shelf from Pensacola to Tampa. Diet studies suggest that it may feed near the seafloor, unlike their Bryde’s whale cousins. They may have lived all across the Gulf of Mexico at the 100-400m line at one time. They prefer warmer waters and do not seem to conduct long migrations.

The area where the Rice’s whale currently exists. Image: NOAA.

Being listed under the Endangered Species Act, NOAA National Marine Fisheries (NMFS) was required to develop a recovery plan for the whale. NMFS conducted a series of five virtual workshops between October 18 and November 18 in 2021. Workshop participants included marine scientists, experts, stakeholders, and the public. There were challenges identified from the beginning. Much of the natural history of this new whale was not well understood. Current and historic abundance, current and historic distribution, population structure and dynamics, calving intervals and seasonality, diet and prey species, foraging behavior, essential habitat features, factors effecting health, and human mortality rates all needed more research.

At the end of the workshop the needs and recommendations fell into several categories.

Management recommendations

- Create a protected area

- Restrict commercial and recreational fishing in such – require ropeless gear

- Require VMS system on all commercial and recreational vessels

- Require reporting of lost gear and removal of ghost gear

- Risk assessment for aquaculture, renewable energy, ship traffic, etc.

- Prohibit aquaculture in core area and suspected areas

- Reduce burning of fossil fuels

- Prohibit wind farms in core area

- Renewable energy mitigation – reduce sound, night travel, passive acoustic

- Develop spatial tool for energy development and whale habitat use

- Require aquaculture to monitor effluent release

- Develop rapid response focused on water quality issues

- Develop rapid response to stranding events

- Reduce/cease new oil/gas leases

- Reduce microplastics and stormwater waste discharge

- Work with industry to use technologies to reduce noise

- Reduce shipping and seismic sound within the core area

- Restrict speed of vessels

- Maintain 500m distance – require lookouts/observers while in core

- Consider “areas to be avoided”

Monitoring recommendations

- Long-term spatial monitoring

- Long-term prey monitoring

- Electronic monitoring of commercial fishing operations

- Necropsies for pollution and contaminants

Outreach and Engagement are needed

Top Threats to Rice’s Whale from the workshop Include:

- Small population size – vessel collisons

- Noise

- Environmental pollutants

- Prey – Climate change – marine debris

- Entanglement – disease – health

- Offshore renewable energy development

The Endangered Species Act (ESA) requires the designation of critical habitat for listed species. In July 2023 NOAA proposed the area along the U.S. continental shelf between 100-400 meters depth as critical habitat. Comments on this designation were accepted through October 6, 2023.

The proposed protection zone for the Rice’s whale including the core area. Image: NOAA.

Vessel strikes are a top concern. It is understood that the most effective method of reducing them is to keep vessels and whales apart and reduce vessel speeds within the approved critical habitat.

On May 11, 2021, NOAA Fisheries received a petition submitted by five nongovernmental agencies and one public aquarium to establish a year-round 10-knot vessel speed limit in order the protect the Rice’s whale from vessel collisions. The petition included other vessel mitigation measures. On April 7, 2023, NOAA published a formal notice in the Federal Register initiating a 90-day comment period on this petition request. The comment period closed on July 6, 2023, and they received approximately 75,500 comments. After evaluating comments, and other information submitted, NOAA denied the petition on October 27, 2023.

NOAA concluded that fundamental conservation tasks, including finalizing the critical habitat designation, drafting a species recovery plan, and conducting a quantitative vessel risk assessment, are all needed before we consider vessel regulations. NOAA does support an education and outreach effort that would encourage voluntary protection measures before regulatory ones are developed.

On that note, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) did issue voluntary precautionary measures the industry could adopt to help protect the Rice’s whale. These include:

- Training observers to reduce vessel collisions.

- Documenting and recording all transits for a three-year period.

- All vessels engaged in oil and gas, regardless of size, maintain no more than 10 knots and avoid the core area after dusk and before dawn.

- Maintain 500m (1700 feet) distance from all Rice’s whales.

- Use automatic identification system on all vessels 65’ or larger engaged in oil and gas.

- These suggestions would not apply if the crew/vessel are at safety risk.

So…

This is where the story is at the moment…

This is what is up with the Rice’s whale in the Gulf of Mexico.

We will provide updates as we hear about them.

References

1 An Overview of Protected Species in the Gulf of Mexico. NOAA Fisheries Service, Southeast Regional Office, Protected Resources Division. 2012. https://www.boem.gov/sites/default/files/oil-and-gas-energy-program/GOMR/NMFS-Protected-Species-In-GOM-Feb2012.pdf.

2 Rosel, P.E., Mullin, K.D. Cetacean Species in the Gulf of Mexico. DWH NRDA Marine Mammal Technical Working Group Report. National Marine Fisheries Service. Southeast Fisheries Science Center.

https://www.fws.gov/doiddata/dwh-ar-documents/876/DWH-AR0106040.pdf.

3 A New Species of Baleen Whale in the Gulf of Mexico. 2024. NOAA Fisheries News.

https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/feature-story/new-species-baleen-whale-gulf-mexico.

4 Rice’s Whale. NOAA Fisheries Species Directory.

https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/species/rices-whale.

5 Rice’s Whale. Marine Mammal Commission.

https://www.mmc.gov/priority-topics/species-of-concern/rices-whale/.

6 Rice’s Whale: Conservation & Management. NOAA Species Directory. 2024.

https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/species/rices-whale/conservation-management.

7 BOEM Issues Voluntary Precautionary Measures for Rice’s Whale in the Gulf of Mexico. 2023. U.S. Department of Interior. Bureau of Ocean Energy Management.

https://www.boem.gov/newsroom/notes-stakeholders/boem-issues-voluntary-precautionary-measures-rices-whale-gulf-mexico.

8 NOAA Fisheries Denies Petition to Establish a Mandatory Speed Limit and Other Vessel Mitigation Measures to Protect Endangered Rice’s Whales in the Gulf of Mexico. NOAA Fisheries News. FB23-079. Gulf of Mexico Fishery Bulletin. October 27, 2023.

https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/bulletin/noaa-fisheries-denies-petition-establish-mandatory-speed-limit-and-other-vessel-0#:~:text=NOAA%20Fisheries%20denied%20a%20petition,with%20rulemaking%20at%20this%20time..

9 Petition to Establish Vessel Speed Measures to Protect Rice’s Whale. NOAA Fisheries. Protected Resources and Actions.

https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/action/petition-establish-vessel-speed-measures-protect-rices-whale.

10 Denial of Gulf Protections Could Lead to the “Permanent Loss” of Rice’s Whale. Jim Turner. WUSF News. October 31, 2023.

https://www.wusf.org/environment/2023-10-31/denial-of-gulf-protections-could-lead-to-the-permanent-loss-of-rices-whales.

by Rick O'Connor | Apr 20, 2024

The Snake Watch Project is one that is helping residents in the Pensacola Bay area better understand which species of snakes are most encountered, where they are encountered, and what time of year. The project began in 2022 and over the last two years between 50-60% of the 40 species/subspecies of snakes known in the Pensacola Bay area have been encountered. The majority of these encounters have been in the spring, with garter snakes, black racers, banded water snakes and cottonmouths being the most common.

The eastern garter snake is one of the few who are active during the cold months.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

The 1st quarter reports cover the winter months, and you would expect fewer encounters – but encounters do happen. In 2022 there were only 6 encounters during the winter months. There was one mid-sized snake (between 12-24” maximum length), 2 large snakes (greater than 3’ maximum length), 1 water snake and 2 cottonmouths for a total of five species. In 2023 there was a significant increase in 1st quarter reports. There were 57 encounters (26% of the total for the year) and 13 species logged.

- Two species of small snakes (less than 12” maximum length) were encountered three times.

- Three species of mid-sized snakes were encountered nine times, this included an encounter with the eastern hognose snake.

- Six species of large snakes were encountered 17 times. These include the rarely seen eastern kingsnake and Florida pine snake.

- Three species of water snakes were encountered, including the green water snake.

- The cottonmouth was encountered 10 times during the 1st quarter of 2023.

This increase in sightings may be more a result of more people interested in the project than a true increase in snake activity, but it does provide us with information on snake activity during the winter months. Eastern garter snakes, eastern ribbon snakes, banded water snakes, and cottonmouths were the most frequently encountered.

A cottonmouth found on the trail near Ft. Pickens.

Photo: Ricky Stackhouse

Snake encounters during the 1st Quarter of 2024 are down. This year 27 encounters occurred logging eight species. The cottonmouth continues to be the most encountered snake in our area and the only one who was encountered in double digits (n=11). Other species encountered included the eastern garter snake, eastern ribbon snake, gray rat snake, corn snake, southern black racer (encountered every month), eastern coachwhip, banded water snake (encountered every month), and the cottonmouth (also encountered each month this quarter).

We will continue to log encounters during the spring. If you see a snake, please let Rick O’Connor know at roc1@ufl.edu.

by Rick O'Connor | Apr 20, 2024

Cogongrass (Imperata cylindrica) is one of the most noxious weeds in the U.S. and has been a problem in the agricultural and timberland for decades. In more recent years it has been found on our barrier islands. Stands of cogongrass on the beaches are not as massive and dense as they are in the upland regions of our district, but now is the time to try and manage it before it does. And NOW is the time to identify whether you have it on your property or not – it is in seed.

Cogongrass shown here with seedheads – more typically seen in the spring. If you suspect you have cogongrass in or around your food plots please consult your UF/IFAS Extension Agent how control options.

Photo credit: Mark Mauldin

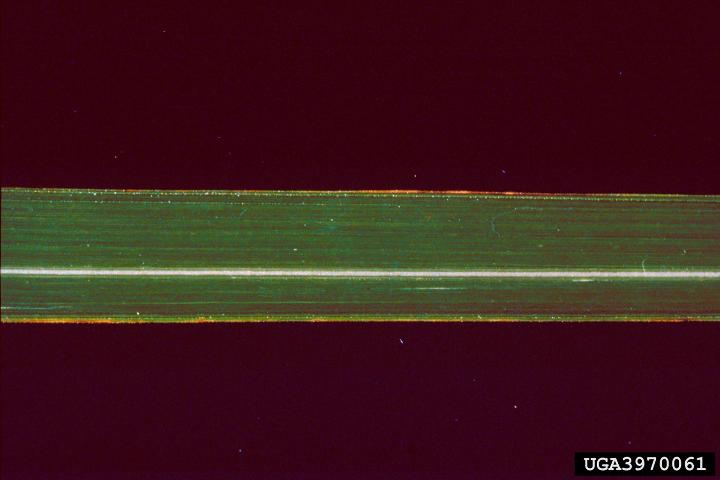

Cogongrass produces blades that resemble St. Augustine but are taller and wider. The blades can reach a height of three feet and the color is more of a yellow green (lime green) than the deep green of St. Augustine. If you can touch the blade, you will notice that the midline of the parallel leaf veins is off center slightly and the edges of the blades are serrated – feeling like a saw blade when you run fingers from top to bottom. They usually form dense stands – with a clumping appearance and, as mentioned, it is currently in seed, and this is very helpful with identification.

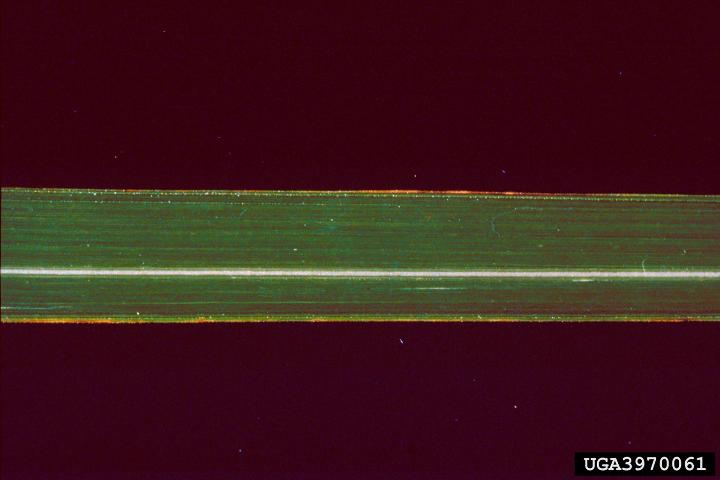

The midline vein of cogongrass is off-center.

Photo: UF IFAS

The seeds are white, fluffy and elongated extending above the plant so the wind can catch them – similar to dandelions. These can easily be seen from the highway or riding your bike through the neighborhoods. As mentioned above, if you see seeds like this you can confirm the identification by examining the leaf blades. You can also send photos to your county extension office.

The white tufted seeds of cogongrass.

Photo: University of Georgia

If the identification is confirmed the next step is to report the location on EDDMapS – https://www.eddmaps.org. You can also do this with the free app IveGotOne (which can be found on the EDDMapS website or any app store). HOWEVER, you cannot report private property without their permission.

The next step would be management. It is not recommended to mow or disturb the plant while in seed. Herbicide treatment is most effective in the fall. Many will mow the plant, allow the grass to resprout no more than 12 inches, and treat this with an herbicide. It is recommended that you contact your county extension office for recommendations as to which herbicide to use and how.

The negative impacts of this noxious grass have been an issue in the upland communities for decades. There have been few major issues with it in the coastal zone, but early detection rapid response is the most effective management plan to keep negative impacts from occurring. We encourage coastal communities to survey for cogongrass while it is in seed and develop a management plan for the fall.