by Rick O'Connor | Dec 15, 2025

It is understood that rattlesnakes are carnivores and will select some form of meat for their food. The general principle is to select something that is easy to kill and requires less energy to do so. Most rattlesnakes will select rodents but depending on the species and the part of the world they are in, some will select lizards or other prey.

Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake.

Photo: Bob Pitts.

Due to their long periods of hibernation and/or aestivation, their feeding seasons are shortened. If you add low prey availability when they emerge from hiding, the feeding season is shorter still. They respond by binge eating – basically gorging on prey as often as they can. They may consume massive meals that will take over a week to digest.

Rattlesnakes who feed on rodents over lizards will grow larger. Many species have young with bright pink or yellow tips on their tails, much like cottonmouths and copperheads. These are used to lure small prey such as lizards and toads. They are predominantly ambush hunters, lying in wait for selected prey to wander into striking range. They like spots where they are half in the shade, half in the sun to do this.

Here is a scenario…

In the spring, when the temperature reaches 70°F, rattlesnakes will leave the hibernacula they used for hibernation. Having not eaten in a while, food is on their mind. They will use their sense of smell to find the trails of their potential prey, find a good ambush spot, and wait. Some studies suggest they sleep while waiting. They may first detect their prey by seeing it. It could be by hearing or smelling. Or by a combination of these. They will begin to flick their tongues – using the Jacobsen’s organ – to further identify the target. When within range, the facial pits can help “see” the target and assist in accuracy of their strike.

The strike is extremely fast. The snake injects their venom, releases, re-coils, and folds their fangs back into their sheath. The target often will run but is usually dead within a minute and not far away. The rattlesnake will now find the scent trail with their tongue and follow its meal. It can take several minutes to an hour to find it. Once found the prey is dead and already in the process of digestion due to some of the enzymes within their venom. In some prey the rattlesnake may not release and rather hold on to the prey after the bite. This often happens when they select birds, possibly due to the difficulty of finding them because they may fly before they die. Another interesting twist to this scenario holds for the timber rattlesnakes, who sometimes lie at the base of a tree with their heads facing up the trunk waiting on an unaware squirrel coming down.

Swallowing the prey involves “unhinging” their lower jaw making the diameter of their mouths larger. This way rattlesnakes can swallow large prey such as squirrels and rabbits. They have six rows of smaller pointed teeth in their mouths. There are two rows on the lower jaw, two on the upper, and two on the roof of their mouths. With the fangs folded back in their sheath, they begin to grab the prey with one set of jaws (the right or left) pull in, then alternate with the other jaw. It appears they are “walking the prey down” their throat. There is a tube called the glottis on the forward portion of the lower mouth that is used for breathing while their mouth is full. They have been seen taking breaks and resting while this process is ongoing. After swallowing, they re-align their lower jaw and find a place to rest and digest the meal.

Being ectothermic they will need to find warmth to digest their meal. They require internal temperatures between 80-85°F for proper digestion, so, they will need to find a location where there is good sunlight but enough cover to hide them. Depending on the size of the meal, digestion can last up to a week.

This scenario can be altered if prey density is low. If it is, rattlesnakes may move, and forage more than they typically do. As you can see, an approaching human during any part of this scenario would be unwanted by the snake.

In the next article we will take a closer look at the venom of these snakes.

References

Rubio, M. 2010. Rattlesnakes of the United States and Canada. ECO Herpetological Publishing & Distribution. Rodeo, New Mexico. pp. 307.

Gibbons, W., Dorcas, M. 2005. Snakes of the Southeast. The University of Georgia Press. Athens, Georgia. pp. 253.

Graham, S.P. 2018. American Snakes. John’s Hopkins University Press. Baltimore, Maryland. pp. 293.

by Rick O'Connor | Dec 8, 2025

We will begin with a statement most know, but bears repeating… Snakes are just another animal trying to get through the day. They need to eat, avoid being eaten, find a place to sleep, and – at some point in the year – find a mate. They are no different than raccoons or hawks. But our reactions to these animals are very different to our reaction to raccoons and hawks. When hiking in the woods when someone says “bald eagle” the reaction is uplifting, maybe get a photo. But if someone says “snake” the reaction is different. If they say “rattlesnake” that reaction increases several magnitudes. In Manny Rubio’s book on rattlesnakes, he mentions that 50% of our population is “uneasy” about them and 20% are terrified of them – ophidiophobia is a real thing. That said, rattlesnakes are part of the barrier island ecology, and it is good to learn more about them.

This eastern diamondback rattlesnake was seen crossing a dirt road near DeFuniak Springs shortly after the humidity dropped.

Photo: Lauren McNally

Rattlesnakes are only found in the new world. There are 30 species listed in the U.S. and Canada and three of those live in Florida. One of them, the eastern diamondback rattlesnake, lives on our barrier islands. The pygmy rattlesnake may as well, but I have not encountered it (nor have heard of others encountering). The canebrake/timber rattlesnake is not common in Florida, and I have never heard of them on our islands.

These snakes differ from others in that they possess modified scales at the tip of their blunt tails we call rattles. Many snakes vibrate their tails when alarmed but this snake’s vibrations can be heard at a distance (up to 20-30 feet sometimes) to warn potential predators they are there. Each time the snake sheds its skin it will leave a new segment on the rattle. This is not a good way to age the snake however because they may shed several times in one year and older segments can break off. There have been reports of rattlesnakes with deformed tails and no rattles at all, but this is rare.

They also possess facial pits that have cells which can detect temperature radiating from an object, including “warm blooded” prey, while hiding. These thermal receptors lie along the bottom of the facial pit and are connected to the optic nerve; thus, they can sort of “see” heat.

Their eyesight is not as good as birds and mammals, and they have an elliptical pupil. They appear to use their eyesight in determining the size of the approaching animal and thus, their reaction to it.

They have nostrils but smell does not seem to play as important a role as Jacobsen’s organ does. This organ is found on the roof of their mouths. Rattlesnakes (all snakes) will flick their forked tongues to collect air molecules and stick the tip of each fork into a groove in the roof of their mouths that lead to this organ. Here they can taste/smell what is within their environment. The “taste” of potential prey will increase the frequency of tongue flicks and could cause the snake to move forward.

The fangs are the part of this animal we are most concerned about. They are hollow tubes connected to a venom gland which are located behind each jaw and give the snake the triangular head shape they are known for. These fangs are folded in a sheath so that they can close their mouths. Whether only one or both fangs are extended during a bite is controlled by the snake. Fangs often break off but smaller new ones are ready to replace them when needed. They will replace these fangs every two months, one at a time.

The strike involves opening the mouth, extending the fangs 90°, opening the mouth 180°, thrusting forward, bite down, inject, recoil, re-fold fangs, and back into the attack position. There are “offensive” and “defensive” strikes. Venom is “expensive” for snakes to produce and is meant for killing prey. The amount injected (if any at all) is controlled by the snake. A “defense” strike is slightly elevated. The upward angle reduces thrust and penetration depth.

Other general characteristics of rattlesnakes includes a triangular shaped head, most have a dark “mask” over their eyes, scales protruding over the eyes, keeled scales giving them a dry/rough appearance, and the males have longer tails than the females.

In our next post we will look at rattlesnake predation.

References

Rubio, M. 2010. Rattlesnakes of the United States and Canada. ECO Herpetological Publishing & Distribution. Rodeo, New Mexico. pp. 307.

Gibbons, W., Dorcas, M. 2005. Snakes of the Southeast. The University of Georgia Press. Athens, Georgia. pp. 253.

Graham, S.P. 2018. American Snakes. John’s Hopkins University Press. Baltimore, Maryland. pp. 293.

by Rick O'Connor | Nov 10, 2025

Over the last decade human-bear encounters have increased across Florida, including the Panhandle. Recently the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) posted advice on how we can prepare for the fall season.

Florida Black Bear visiting an easy food source.

They mention that fall is a time when bears begin seeking additional food sources to prepare for winter. An adult bear can consume up to 20,000 calories a day during this prep period. All creatures will seek the easiest source of food, reducing energy effort in capturing, and will take the opportunity to raid garbage cans, pet food left outside, and even bird feeders. Here are tips FWC suggests.

- Never Feed Bears. Doing so will reduce their natural fear of humans, and intentionally doing so is illegal in Florida.

- Secure Food and Garbage. Some suggestions on how to do this…

- Keep your trash can in a sturdy shed or garage and do not place on the street until morning.

- Modify your trash can to make it more secure. Tips for this can be found from FWC at Instructions on Making a Trashcan Bear-Resistant.

- Purchase a bear resistant trash can. Bear Resistant Trash Containers.

- They are attracted to gardens, compost piles, beehives, and livestock. Take measures to reduce their ability to reach these.

- Pick ripe from fruit trees and remove fallen fruit from the ground.

- Remove, or secure, bird feeders. If you want to feed winter birds, place only enough food for the delay and remove it at night. You can find other suggestions to help winter birds at this site – Attract Backyard Birds, Not Backyard Bears – BearWise.

- Never leave pet food outdoors. This is actually a good suggestion to reduce raccoon, coyote, and other wildlife encounters. If you must feed your pet outside, do so for only short periods and bring all food after dark.

- Clean and store grills.

- Alert neighbors to bear activities. Share these tips with them and your HOA.

Bears are generally afraid of humans and are not aggressive but can become so when there are mothers protecting cubs, and dogs. 60% of all human-bear encounters involved dogs. When walking your dogs keep them on a short leash and be aware of your surroundings and your dog’s reaction to your surroundings. Before letting your dog out at night turn the exterior lights on and off several times and bang the door. Keep in mind they will be moving more this time of year and are most often encountered on the roads at dawn and dusk.

If you have further questions, or need further information, search the FWC website.

by Rick O'Connor | Nov 3, 2025

Each year Florida Sea Grant conducts a summer survey of selected invasive species of concern in the coastal area of Pensacola Bay.

Below are the results of the 2025 survey.

Beach vitex

Beach vitex is an invasive vine that grows in the sands of our beaches and dunes. Our records currently show 108 sites in the bay area where the plant exists.

| Location |

Number of sites |

Surveyed in 2025 |

| Gulf Breeze |

3 |

No |

| Pensacola Beach |

68 |

Yes |

| Perdido Bay |

2 |

No |

| Perdido Key |

3 |

No |

| Gulf Islands National Seashore – Naval Live Oaks |

24 |

No |

| Gulf Islands National Seashore – Ft. Pickens |

1 |

No |

| Navarre Beach |

8 |

No |

| Location |

Private property |

Public property |

Status |

| Gulf Breeze |

1 |

2 |

One of the public sites HAS been removed. |

| Pensacola Beach |

42 |

26 |

25 sites have had the plant removed and it has not returned.

26 sites have had the plant removed BUT it has returned.

16 sites have never been treated. Most of these are private properties.

1 site status unknown (construction currently ongoing). |

| Perdido Bay |

1 |

1 |

Status unknown. |

| Perdido Key |

2 |

1 |

Private property is being treated. Status of public site is unknown. |

| Gulf Islands National Seashore – Naval Live Oaks |

0 |

24 |

Unknown. |

| Gulf Islands National Seashore – Ft. Pickens |

0 |

1 |

Status unknown. |

| Navarre Beach |

? |

? |

Status of all is unknown. |

Vitex beginning to take over bike path on Pensacola Beach. Photo credit: Rick O’Connor

Tilapia

We estimate there are about 60 Blue and Nile tilapia living in the upper “right arm” of Bayou Chico east of “W” Street (could be under estimated). There was a collection effort this year and 25 of those fish were removed. Surveys west of “W” street have not shown in evidence of tilapia invasion. We encourage waterfront residents of Bayou Chico to report any sightings of this fish.

Tilapia found in Pensacola.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

Lionfish

It is well known that lionfish exist in the Gulf. Whether, and how many, exist within the bay is unknown. Since we began monitoring (2013) we know of 3 records within Big Lagoon – all were removed. In the last five years there have been reports of lionfish near the fishing pier at Ft. Pickens. Volunteer removals have removed at least 10 fish from this location. No surveys or removals occurred in 2025. Surveys were conducted at the snorkel reef near Park West, and the artificial reefs near the Grand Marlin in 2025 – no lionfish were found.

Photo courtesy of Florida Sea Grant

Cogongrass

Cogongrass has been found on Perdido Key. No surveys were conducted in 2025, and status is unknown.

Cogongrass shown here with seedheads – more typically seen in the spring. If you suspect you have cogongrass in or around your food plots please consult your UF/IFAS Extension Agent how control options.

Photo credit: Mark Mauldin

Cuban Treefrogs

Several reports of additional Cuban treefrogs were submitted in 2025. According to the national database EDDMapS, there are 18 records from the Pensacola Bay area – 1 from Gulf Shores.

| Location |

Number of CTFs reported |

| Perdido Key |

3 |

| Downtown Pensacola |

3 |

| Ensley area |

3 |

| Near UWF |

1 |

| Near Scenic Heights |

1 |

| Pensacola Beach |

2 |

This is most likely underreported. If you believe you have a Cuban treefrog, please contact the Escambia County Extension and/or report to the EDDMapS database. If you are interested in setting up a Cuban treefrog trap – contact the Extension Office to learn how.

Cuban Treefrog.

Photo by: Dr. Steve Johnson

Giant salvinia

This invasive plant has been found in several locations within Bayou Chico. We will be removing a small portion of the problem near “W” Street this year. We encourage waterfront homeowners on Bayou Chico to assist with removal, and destruction, of this plant.

Active growing Giant Salvinia was observed growing out of the pond water on to moist soils and emerging cypress and tupelo tree trunks. Photo by L. Scott Jackson

Green mussels

There was one UNCONFIRMED report of this invasive mussel in Pensacola Bay. If you believe you have seen this – please contact the Escambia County Extension Office.

This cluster of green mussels occupies space that could be occupied by bivavles like osyters.

Nutria

There is a small population of nutria living on Perdido Key. At this time, they seem to be contained in a small location. If you believe you have seen this animal in your neighborhood, please contact the Escambia County Extension Office.

A dead nutria found along a roadside in Escambia County.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Tiger shrimp

The invasive tiger shrimp were reported in Pensacola Bay around 2013. We have had no reports since. EDDMapS shows 9 records from Pensacola Bay and 1 record from Milton.

The nonnative Asian Tiger Shrimp – also known as the Black Tiger Shrimp

Thrush Cowries

This is a new invasive species first reported this summer. The snail has been found on the pilings of the snorkel reef at Park East, Navarre snorkel reef, Pensacola Beach fishing pier, Casino Reef, and along the beach near the Flora-Bama. If you see this snail, please contact the Escambia County Extension Office.

The thrush cowrie.

Photo: FWC.

by Rick O'Connor | Nov 3, 2025

In Part 1 of this series, we mentioned many of the issues that mankind is facing, but climate change may be the largest. In this series we have taken a journey on how humans got to this point. We began with our origins and how we dispersed across the planet. Our need for resources, such as food, water, space, and energy. And how our uncontrolled population growth has led to a greater need for these resources and the environmental impact obtaining them has caused. So, here we are… a planet of 8 billion people all seeking and competing for needed resources. Our methods of obtaining them have actually led to something unfathomable… we are actually changing the climate – and this could have several negative impacts for us.

Our fragile Earth

Photo: NOAA

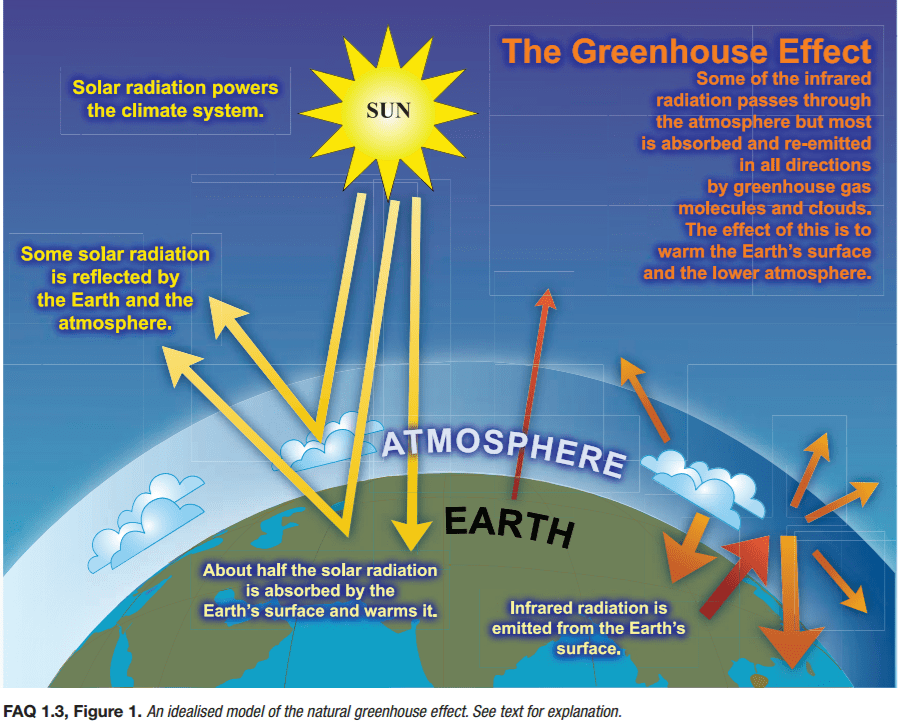

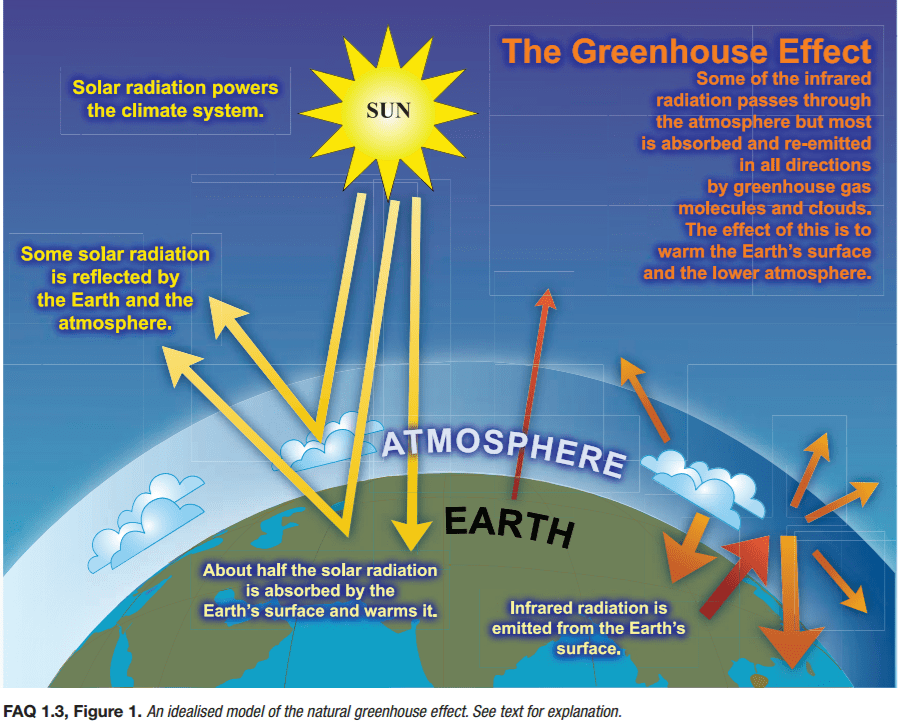

Much of the change in climate is due to the increased production of carbon dioxide, methane, and other “greenhouse gases”. Most of the greenhouse emissions are from industrial processing and the burning of fossil fuels. These gases act as a greenhouse layer for the planet – allowing solar radiation through the atmosphere to heat the surface – but blocking rising heat from escaping – causing a rise in global temperatures.

The greenhouse effect.

Image: NOAA

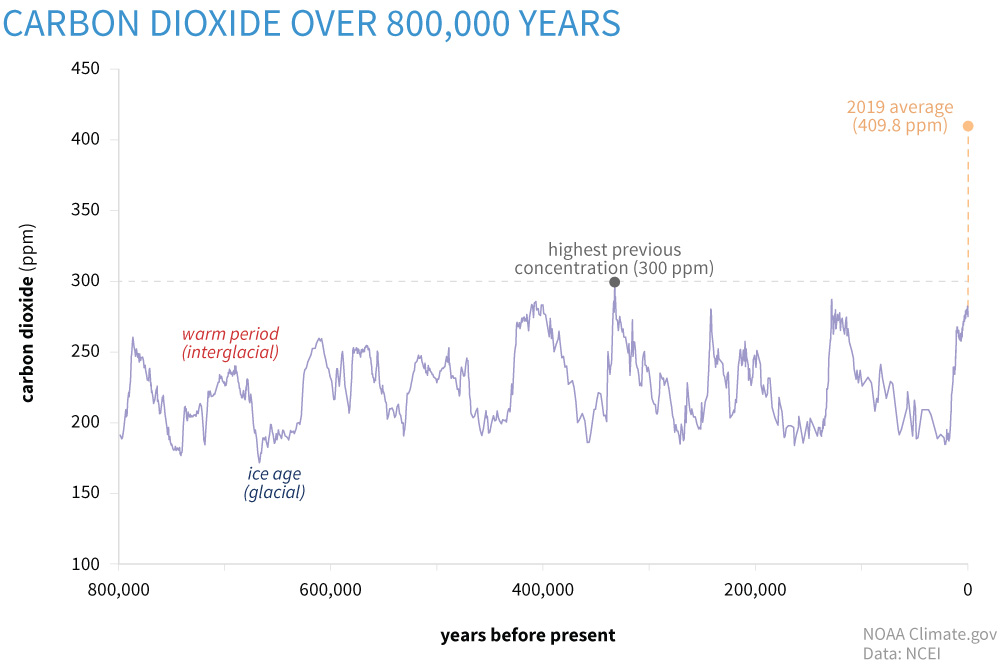

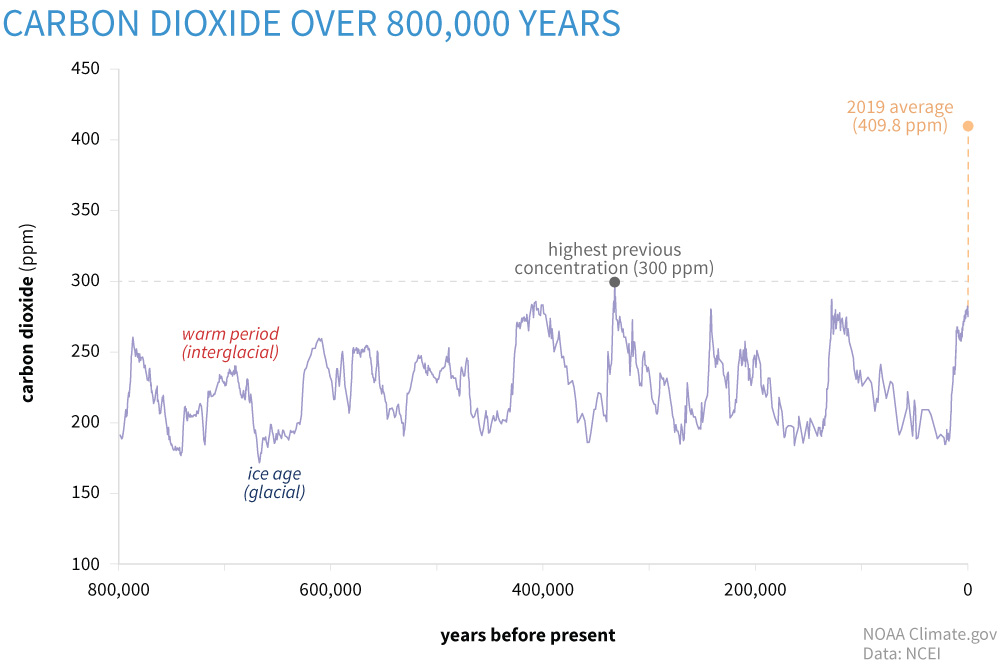

Everyone has seen the graphs of both carbon emissions and global temperature changes over the last couple of centuries. The acceleration of this warming began during the industrial revolution and continued to increase during the 20th century.

Changes in carbon dioxide levels up to 2019.

Image: NOAA

Our planet actually functions well under a natural form of greenhouse. Carbon dioxide released by photosynthetic plants, volcanic eruptions, and other natural processes, provides a layer in the atmosphere that creates a climate system that allows creatures to survive. The equatorial portion of our planet receives the greatest amount of solar energy and the heat produced from this is moved towards the poles by the ocean and wind currents – dispersing heat to places that would otherwise be colder than they are. However, the increased production of greenhouse gases has escalated the warming.

The oceans have been described as “heat sinks” – collecting heat near the equator and dispersing it further north via the ocean currents. These currents rotate clockwise in the northern hemisphere carrying the warmer water along the western shores of the oceans – eastern Asia and North America – creating wetter, more humid climates – dissipating much of the heat by the time it reaches the poles. The cooler currents then pass the eastern shores of the oceans – western North America, Europe, and Africa – where humidity and rainfall are less. Warm ocean currents provide warm humid air over the land creating rainfall and densely vegetated ecosystems – such as the southeastern United States, and southeast Asia. Cool ocean currents do the opposite – creating arid ecosystems.

Climate models have suggested that a warmer ocean could intensify this process. Warmer land and water will cause a warmer air mass above them. Warm air rises, which decreases the air pressure over that portion of the earth’s surface creating what we call low pressure cells-low pressure systems. As many of us know, low pressure cells create storms, and we have experienced more intense storms all over the country. In the last few years these intense storms have created intense flooding events and tropical storms. One community in the Big Bend of Florida has experienced 3 tropical storms in 13 months. The drier conditions of the cold current coasts have intensified wildfires. All of these changing climatic effects have come at a great cost – both in property damage and in human lives. They have also increased the cost of trying to manage them and will most likely increase cost of insurance to rebuild from these disasters.

This squall line formed early in the morning. One of many morning thunderstorms formed over a period of a week in the summer of July 2023.

Photo” Rick O’Connor

There are also the impacts of climate on the rest of the planet. Warmer months could cause, and have caused, changes in the local biology. There are reports of lobsters moving north from Maine to Canada; this could happen for other fisheries as well. You will (have) seen the same in agriculture. Planting zones have slowly migrated north forcing farmers to re-think what they are growing on their land – what crops can they support. We could see similar impacts on aquaculture, timber, and more.

Another impact that is already playing out is the lack of water in the drier areas of the planet. The American southwest has already experienced “water wars” and it will continue to be a problem – possibly escalating in the future.

The basic solution to this problem is simple – either reduce the amount of greenhouse gases we are releasing (re-think how we obtain our energy needs), develop methods of removing greenhouse gases from the atmosphere (and before we release), or both.

Easier said than done…

Our investments, and comfort, with fossil fuels are very deep. Many energy companies have been developing new energy technologies for the last few decades – but it is expensive to convert an entire energy system – it will take time and money – both that seem to be in short supply at this time. That said, this issue is not going away and our communities need to move closer to solving them. The University of Florida, and many other universities, have been experimenting and developing methods to help turn this thing around. If your community, business, or agency has questions, or need more information, on this topic – reach out to your local county Extension office.