by Rick O'Connor | Dec 8, 2017

The observations I made of rattlesnakes is just that… observations, there is no scientific study I am aware that supports what I appear to have seen, but I have noticed it – more than once now.

Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake crossing road at Eglin AFB. Photo: Carrie Stevenson

The eastern diamondback rattlesnake (Crotalus adamanteus) is a legendary animal in the southeast United States. William Bartram mentions it several times during his travels through Florida in the 1770’s. His Florida nickname “Pug Puggy” actually came from an incident where he killed a large one in a garden of a Seminole camp. Almost every story about the colonial/settling period of state, whether fiction or non-fiction, includes this snake. They are the largest venomous snake in the U.S., reaching up to six feet, and can have the girth of a man’s arm. They have a large head, holding large venom glands, and have a strike range of 33% their body length – the stuff of legends.

However, few people of died from this animal. One website list 53 fatal snakebites in the United States since 1900, 11 are listed “prior to 1900”. Of the 53 snakebites, 34 (64%) were from rattlesnakes – all 11 (100%) of the “prior to 1900” were rattlesnakes. However, there are a reported 16 species of rattlesnakes in the U.S., only three live in the southeast. From this list, there are only three confirmed Eastern Diamondback bites (5%), and an additional 7 that “may” have been. They were identified as rattlesnakes and the victims lived in the southeast, but the bite could have been from the timber or pygmy rattlesnake. The vast majority of lethal rattlesnake bites come from out west. Granted, in the early part of our state’s history many rattlesnake bites went unreported, however 3 confirmed deaths (10 possible) since we became a state is not that many when compared to the number of Floridians who have died in automobile accidents or violent crimes. That said, this is still a legendary animal that many fear, and the snake lives on Pensacola Beach.

In the past month, I have received several photographs of the eastern diamondback seen in the National Seashore. The observation – they seem to be more common when we are not around. No doubt, they were probably once common on the island. Many are surprised by this because the only way to access Santa Rosa Island, initially, was to swim – but rattlesnakes are good swimmers. They do not prefer the water, but have no problem crossing it. They are primarily consumers of rodents, taken prey as large as rabbits if they can, and hunt primarily at night – so viewing during the day is not common.

However, when the road to Pickens was closed after Hurricane Ivan, daytime encounters with eastern diamondbacks increased. There were numerous reports of individuals seeing them moving around the park. Then the road re-opened, and no one saw them anymore. Hurricane Nate caused enough damage that the park, once again, had to close for repairs – and the photos began to come in. It will be interesting to see if the number of encounters begins to decline no that it has re-opened. Are these snakes aware of our presence and seek refuge? It would be nice to know they did, but both Ivan and Nate arrived in the fall when rattlesnakes begin to move for breeding. How many of these snakes would be seen whether the road was open or not. I know when the road is open I do not hear as much from the public. I also know that recently FWC was requesting reports of encounters with this snake because they feared it was declining across the state. Along with several other species of local snakes – such as the Southern Hognose (Heterodon simus) and the Florida Pine Snake (Pituophis melanolucas migitus), they were asking the public to report sightings. They recent removed the eastern diamondback from this list – suggesting that encounters were more common than they thought. Again, maybe a case of “I’m here but I’m hiding”.

The familiar face of an Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake.

Photo: Nick Baldwin

For me, it is an interesting observation. I find the animal fascinating, maybe because of its legendary status and rare encounters, but I find it fascinating nonetheless. I certainly understand the safety concerns with having this animal so close to us, but the records of bites and fatalities suggests the threat is not as large as we perceive it. I would certainly recommend homeowners maintain their property as to reduce the risk of an encounter, but know most do – or else you would be seeing more of them. As with sharks, I for one am glad to know they are still around.

by Rick O'Connor | Oct 31, 2017

In our continuing battle with invasive species, northwest Florida is now home to an invasive lizard. Known as both the Cuban and Brown Anole, this animal has been reported from Big Lagoon, East Hill, North Hill, and Gulf Breeze in the Pensacola area. I have seen it at almost every rest area on I-10 between here and Gainesville and in large numbers at some local nurseries.

This Cuban Anole was photographed on a public hiking trail near Perdido Key.

Photo: Jerry Patee

Who is this new invader to our area?

We will start with “new”.

Compared to the rest of the state, it is new. First reported in 1887, this lizard hitchhiked over from its native Cuba and Bahamas via boats. DNA studies suggest there were at least seven different “invasions” of the lizard to Florida. This is not surprising since the lizard is small (between 5-8 inches) and likes moist areas to lay eggs. A fan of warmth, vegetation, and insects – it did very well once it arrived. Like most invasive species, it quickly spreads into disturbed areas… and we have disturbed Florida in a major way. It is now found in all counties within the Florida peninsula and in many, it is the most common lizard seen.

Is it an “invader”?

Yes, in the sense that it moves into disturbed habitats quickly and competes with the native Green Anole (Anole carolinensis). Both lizards are beneficial to humans in that they consume great numbers of insects and spiders. However, the Cuban Anole will consume the eggs and juveniles of the Green Anole. Where the two co-exist, the Green Anole is forced to live higher up in the vegetation. This is a form of resource partitioning where each species is co-existing in the same area but not directly competing. However, biologists are not sure how this co-habitation of the two lizards will affect local ecology. It is currently listed as an invasive species in Florida.

So is it new to the panhandle?

Well, based on records – yes. Based on anecdotal comments – no. Some folks have seen it for some time now. The most probable means for dispersal have been with forms of transportation visiting the panhandle from south Florida and the transport of landscaping plants from south Florida nurseries. One local nursery had a greenhouse over-run with the lizard. If you view the invasive database EDDMaps. It shows 13 records between Alabama and the Aucilla River. There are certainly more than that. EDDMaps has the distribution broken down as:

| County |

Number of Cuban Anole Records |

| Bay |

1 |

| Calhoun |

0 |

| Escambia |

0 |

| Franklin |

0 |

| Gadsden |

0 |

| Gulf |

0 |

| Holmes |

0 |

| Jackson |

1 |

| Jefferson |

0 |

| Leon |

2 |

| Liberty |

0 |

| Okaloosa |

4 |

| Santa Rosa |

4 |

| Wakulla |

0 |

| Walton |

0 |

| Washington |

1 |

Several local residents have sent me photos of the Cuban Anole in Pensacola (used in this article). I will need to post these soon and we will need help from the public posting more. To report anoles, you will need to log into EDDMaps at www.EDDMaps.org. You will need an account, but it is free. You can also download their app “I’ve Got 1”, which can be found on the website. If you have questions about EDDMaps, please contact me at the Escambia County extension office (850) 475-5230.

This Cuban Anole was photographed at the east end of Big Lagoon near NAS Pensacola.

Photo: Carole Tebay

Until then, check your cars before heading back from south Florida and any plants you may buy from nurseries to be sure you are not bringing any friends home. If you are finding them in your yard and wish to control them, contact me at the Escambia County extension office.

References

Anoles. 2017. University of Florida IFAS Gardening Solutions. http://www.gardeningsolutions.ifas.ufl.edu/design/gardening-with-wildlife/anoles.html.

Brown Anole (Anole sageri) Introduced. Savannah River Ecological Laboratory. University of Georgia. http://srelherp.uga.edu/lizards/anosag.htm.

Dunning, S. 2017. The Cuban Anole. NISAW 2017. Panhandle Outdoors Electronic Newsletter. https://nwdistrict.ifas.ufl.edu/nat/2017/02/28/nisaw-2017-cuban-anole/.

EDDMaps. 2017. Distribution Map by County. http://www.eddmaps.org/distribution/uscounty.cfm?sub=18342.

Johnson, S.A. 2011. Focal Species: Cuban Brown Anole. The Invader Updater. Vol 3 (1). http://ufwildlife.ifas.ufl.edu/InvaderUpdater/pdfs/InvaderUpdater_Winter2011.pdf.

Nonnative Species: The Brown Anole. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. http://myfwc.com/wildlifehabitats/nonnatives/reptiles/brown-anole/.

by Rick O'Connor | Oct 6, 2017

Imagine this…

You are a sailor on a 16th century Spanish galleon anchored in a Florida Bay south of Tampa. You, along with others, are ordered to go ashore for a scouting trip to set up a base camp. You transfer over to a small skiff and row ashore to find a forest of root tangled mangroves. There is no dry beach to land so you disembark at the edge of the trees in knee-deep water. The bottom is sandy and your footing is good but you must literally crawl through the tangled mess of mangrove prop roots to finding dry ground. As you do, you encounter spider webs, numerous biting insects, and the bottom becomes muddy and footing is less stable. I am sure I would have returned to the ship to report to the captain that there is nothing of value here – let’s go back to Spain!

The dense vegetation of a black mangrove swamp in south Florida.

Photo: UF IFAS

Along the shores of northwest Florida it would have been different only that they would have encountered acres of grass instead of trees. The approach to Pensacola would have found a long beach of white sand and dunes. Entering the bay, they would have found salt marshes growing in the protected areas, with the rare exception of dryer bluffs in some spots – which is where de Luna chose to anchor. These marshes are easier to traverse than the emergent root system of the mangrove, but the muck and mire of the muddy bottom and biting insects still remain.

For centuries, Europeans have sought to alter these habitats to make them more suitable for colonization. Whether that was for log forts and houses or marinas and golf courses, we have cleared the vegetation and filled the muck with fill dirt. But have we lost something by doing this?

Yes… Yes we have, and some of what we have lost is valuable to us.

We have lost our water quality.

These emergent shoreline plants filter debris running from shore to the sea during rain events. The muck and mire we encounter within the marsh would otherwise entered the bay or bayou. Here it would cloud the water and smother the submerge seagrasses. My father-in-law told me that as a kid growing up on Bayou Texar in Pensacola he remembered clear water and seagrasses. He remembered throwing a cast net and collecting 4-5″ shrimp.

That has changed.

In our modern world, it is not just mud that is running off towards our bays. We can add lawn fertilizers, lawn and garden pesticides, oils and grease from cleaning, and a multitude of other products – including plastics.

We have seen a decline in living resources.

The large shrimp my father-in-law talked about are not as common. He spoke of snapper – very few now. Bay scallops are basically gone in Pensacola and have declined across much of Florida’s gulf coast. Horseshoe crabs have become rare in many locations. Moreover, salt marsh/mangrove dependent species, such as diamondback terrapins, are difficult to find.

Storm drains, such as this one, discharge run-off into local bays and bayous.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Maybe of more concern is the decline of commercially important aquatic species such as crabs, shrimp, and finfish. It is known that 80-90% of these commercially important species spend at least part of their lives in the marshes and mangroves.

And this we are losing.

And then there is the shoreline itself.

The emergent plants the Spanish encountered actually act as a wave break. Sand running off the land is trapped to form a “beach”, albeit a mucky one, and the wave energy is absorbed by the plants reducing the energy reaching the shore. The damage in south Florida from hurricane Andrew was devastating. But that same storm made a second landfall in the marshes of Louisiana and there was little to write about – the marsh absorbed much of the energy. The removal of these vegetated shorelines has enhanced the loss of coastline across the Gulf States.

Can we restore these shores and return these “services”?

Yes…

Whether communities want to or not is another question, but we can.

Studies have shown that a marsh 10′ across from water to land can remove 90% of the nutrients running off. Nutrients can trigger hypereutrophic conditions in the bay – which can lead to algal blooms – which can lead to low dissolved oxygen – which can lead to fish kills and seagrass loss. In addition to removing nutrients, marshes and mangroves can remove a variety of other contaminants and plastics. Many sewage treatment facilities discharge their treated effluent through the coastal plant communities before it reaches the bay, thus improving water quality.

We know that restoring a living shoreline will enhance the biological productivity of the bay. Studies have shown that swamps and marshes can produce an annual mean net primary production of between 8000 – 9000 kcal/m2/year, which is equivalent to tropical rainforest and the open estuary itself.

Finally, living shorelines will stabilize erosion issues, much longer than seawalls and other harden structures. Studies have shown that seawalls will eventually give in. Wave energy is increased when it meets the wall and reflects back. This generates higher energy waves that decrease seagrasses and actually begins to remove sediment around the wall itself. You will see the land begin to erode behind the wall and eventually it begins to fall forward into the bay. The east coast of Florida recently experienced this during hurricane Irma. Interestingly the west coast experienced negative tides. The exposure of these seawalls to an empty bay had the same effect. Without the water pressure to hold them, they began to crack and fall forward. A living shoreline can sustain all of this.

FDEP planting a living shoreline on Bayou Texar in Pensacola.

Photo: FDEP

So how do restore my shoreline?

- You will need a permit. The state of Florida owns land from the mean high tide seaward. To plant above this line you do not need a permit, but you will want to plant at and below to truly restore and benefit from the services. Permitting can be simple or complicated – each property is different. Visit http://escambia.ifas.ufl.edu/permitting-living-shorelines/ to learn more about the process.

- You will need plants. There are a few nurseries that provide the needed species. There is a zonation to the plant community and it is important to put the right plant in the right place. The above link can help with this and the Extension office is happy to visit your location and give recommendations.

- You will need to plant them. Fall and spring are good planting times. A recent project we helped with planted in April and it has been very successful.

- You may want to monitor the success of your project. This not needed, but if interested the Extension office we can show how to do this.I certainly understand why many would rather remove these shoreline ecosystems, but I think you can see the benefits outweigh the problems. It is not an all or none deal. Living shorelines can be designed to allow water access. If interested in learning more contact your county Extension office.

I certainly understand why many would rather remove these shoreline ecosystems, but I think you can see the benefits outweigh the problems. It is not an all or none deal. Living shorelines can be designed to allow water access. If interested in learning more contact your county Extension office.

References

Permitting a Living Shoreline; can a living shoreline work for you? http://escambia.ifas.ufl.edu/permitting-living-shorelines/.

Miller Jr., G.T., S.E. Spoolman. 2011. Living in the Environment: Concepts, Connections, and Solutions. 16th edition. Brooks and Cole Cengage Learning. Pp. 674.

Sharma, S. J. Goff, J. Cebrian, C. Ferraro. 2016. A Hybrid Shoreline Stabilization Technique: Impact of Modified Intertidal Reefs on Marsh Expansion and Nekton Habitat in the Northern Gulf of Mexico. Ecological Engineering 90. Pp 352-360.

by Rick O'Connor | Oct 6, 2017

Back in the spring, I wrote an article about the natural history of this ancient animal. However, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) is interested in the status of horseshoe crabs and they need to know locations where they are breeding – and Florida Sea Grant is trying to help.

Horseshoe crabs breeding on the beach.

Photo: Florida Sea Grant

If you are not familiar with the horseshoe crab, it is a bizarre looking creature. At first glance, you might mistake it for a stingray. It has the same basic shape and a long spine for a tail. But further observation you would realize it is not a stingray at all.

So then… What is it?

When you find one, most are not comfortable with the idea of picking it up to look closer. The spine is probably dangerous and there are numerous smaller spines on the body. Actually, the long spine in the tail region is not dangerous. It is called a telson and is most often used by the animal to push through the environment when needed, as well as righting itself when upside down. It is on a ball-and-socket joint and if you pick them up, they will swing it around – albeit slowly – but it is of no danger. Note though, do not pick them up by the telson – this can damage them.

If you do try to pick them up with your hands on their sides, you will find they are well armored and have numerous clawed legs on the bottom side. At first, you are thinking it is a crab, and the claws are going to pinch, but again we would be mistaken. The claws are quite harmless – they even tickle when handled. I have held them to allow kids to place their hands in there to feel this. However, when held they will bend their abdomen between 90° and 120°, as if attempting to roll into a ball – which they cannot. At this point, they become difficult to hold. Your hands feel they are in the way and the small spines on the side of the abdomen begin to pierce your skin. So, you flip it on its back. It begins to try a 90° bend in the other direction and begins to swing the telson around. This is probably the most comfortable position for you to hold – but I am not sure what the crab thinks about it.

So, what do you have?

Well, you can see why they call it a crab. It has clawed legs and a hard shell. The body is very segmented. You can also see why it is called a “horseshoe”. But actually, it is not a crab.

Crabs are crustaceans. Crustaceans have two body segments – a head and abdomen, no middle thorax as found on insects. This is the case with the horse crab as well.

Crustaceans have 10-segmented legs, though the claw (cheliped) and swimming paddles (swimmerets) of the blue crab count as “segmented legs”. Horseshoe crabs have 10 as well – seems this IS a crab – but wait…

Crustaceans have two sets of antenna – two short ones and two long – horseshoe crabs do not have any antenna. Traditionally biologists have divided arthropods into two subphyla – those with antenna and those without – so the horseshoe crab is not a crab. It is actually more closely related to spiders, ticks, and scorpions.

Blue crabs are one of the few crabs with swimming appendages.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

It is an ancient animal, fossil horseshoe crabs in this form date back over 440 million years – out dating the dinosaurs. There are four different species of today and there probably were more species in the past. Their range extends from the tropics and temperate coastlines of the planet. Today three of the remaining four species live in Southeast Asia. The fourth, Limulus polyphemus, lives along the eastern and Gulf coast of the United States.

Unfortunately, this neat and ancient creature is becoming rare in some parts of its range. There is a commercial harvest for them. Their blood is actually blue and contains properties beneficially in medicine. Smaller ones are used as bait in the eel fishery, and there is always the classic loss of habitat. These are estuarine creatures and are often found in seagrass and muddy bottom habitats where they forage on bottom dwelling (benthic) animals.

FWC is interested in where horseshoe crabs still breed in our state. Some Sea Grant Agents in the panhandle are assisting by working with locals to report sightings. Sea Grant also has a citizen scientist tagging program to help assess their status. Horseshoe crabs typically breed in the spring and fall during the new and full moons. On those days, they are most likely to lay their eggs along the shoreline during the high tide. This month the full moon is October 5 and the new moon is October 19. We ask locals who live along the coast to search for breeding pairs on October 4-6 and October 18-20 during high tides. If you find breeding pairs, or better yet, animals along the beach laying eggs – please contact your local Sea Grant Agent. We will conduct these surveys in the spring and fall of 2018 and post best search dates at that time.

For more information on the biology of this animal read http://escambia.ifas.ufl.edu/marine/2017/04/10/our-ancient-mariner-the-horseshoe-crab/.

References

Barnes, R.D. 1980. Invertebrate Zoology. Saunders College Publishing. Philadelphia PA. pp 1089.

Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. Facts About Horseshoe Crabs https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2008/02/080207135801.htm

Oldest Horseshoe Crab Fossil Found, 445 Million Years Old https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2008/02/080207135801.htm

by Rick O'Connor | Sep 22, 2017

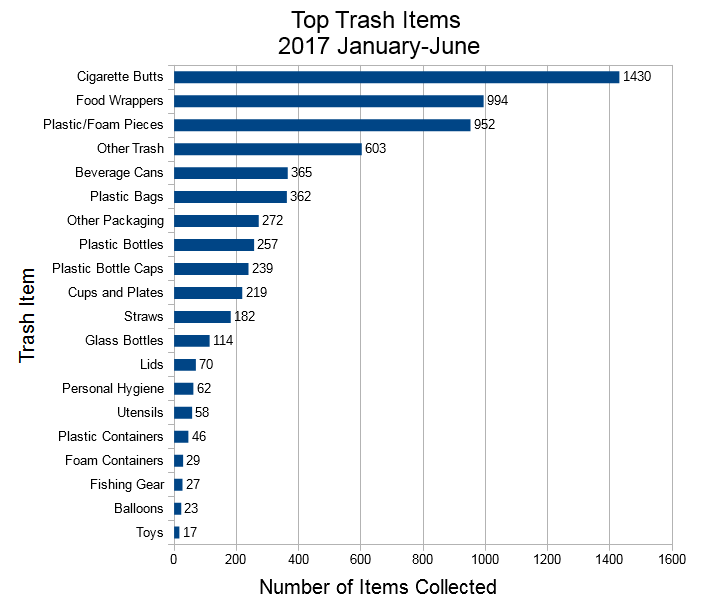

For almost 40 years, the Ocean Conservancy has held the International Coastal Cleanup in September. Across the planet hundreds of thousands of volunteers clean marine debris from their shorelines. The data collected is used by local agencies to manage this problem; such as discontinuing the use of pull tops from aluminum cans. In the last couple of years researchers are trying to make the public aware of another form of plastic most know little about – microplastics.

“Nurdle” are primary microplastics that are produced to stuff toys and can be melt down to produce other products.

Photo: Maia McGuire

Microplastics are defined as pieces measuring 5 mm in length or smaller. These can be large pieces of common plastics that been degraded by sea and sun. They can be small pellets called nurdles that are melted down and poured into molds to produce common plastic products or used to stuff toys. They can also be small beads used as fillers in personal care products, such as toothpaste. Those that are manufactured at this size are called primary microplastics; those that degrade to this size are secondary microplastics.

How Do They Find Their Way to Local Waterways?

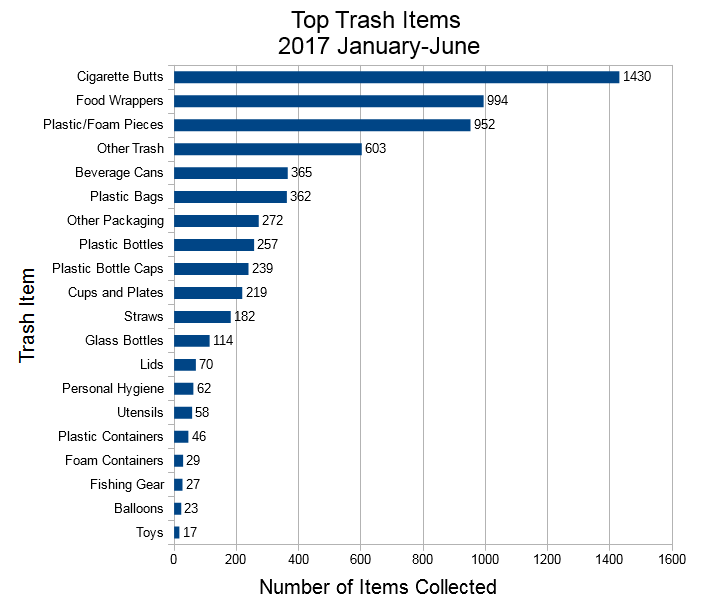

The sources of secondary microplastics is obvious. We either intentional or unintentionally discard our waste into the environment. According to data collected by the local nonprofit group Ocean Hour, cigarette butts are the number item collected during weekly cleanups. Many are not aware that much of the material in a cigarette butt is actually plastic fibers, and many butts are tossed to the ground intentionally. Adhered to these fibers are the products of smoke we are concerned with in our own health – tar, nicotine, and ethylphenol.

Ocean Hours data show other forms of plastics (bags, wrappers, cups, bottles, and caps) are very common. These items are discarded directly, or indirectly, into the environment and eventually end up in our bays and oceans – “all drains lead to sea kid”. Here they are eventually broken down. Some scientists believe all the plastic ever produced is still in the sea, continuing to breakdown smaller but never really going away. I viewed a webinar within the last year where a researcher from the west coast was discussing the “great plastic island” in the Pacific. She showed a photo from the location and you did not really see a lot of large plastic drifting. However, a plankton tow revealed large amounts of microplastics.

Marine debris collected by Ocean Hour during the first half of 2017.

Image: Ethan Barker

Less common are the primary microplastics… but they are there. According to our monitoring in the Pensacola Bay Area, they make up about 20% of the microplastics found. When we wash our faces, or brush our teeth, with plastic filled products these microplastics are washed down the drain to the local sewer treatment facility. Here they remain on the surface of the water that is being treated and are eventually discharged into wetlands, or directly into a water body.

Are These Microplastics Having a Negative Impact on the Environment?

Locally, we are monitoring 22 stations. We are finding an average of 9 pieces of microplastic / 100ml of sample (little more than 3 ounces). This equates to a lot of microplastic in our bay. Science does know that these are small enough to be swallowed by zooplankton in our water column. It plugs their digestive tract and gives them the sensation of being full. Thus, they stop eating and starve. A decline zooplankton, a key component of most aquatic food chains, could affect economically important members higher up the food chain.

Laboratory studies show it may be affecting lower on the food web. When subjected to water containing microplastics, the microalgae Chorella reduced its uptake of carbon dioxide; thus reducing photosynthesis.

In larger species, microplastics have been found in the tissue of some bivalves, including those commercially harvested for human consumption. There is little evidence connecting health related problems of either the bivalve or the human consumer, to microplastic consumption – but there is concern.

There is evidence showing chemical contaminants adhere to the plastics and can increase their concentrations 1 million times. Swallowing plastics with high concentrations of Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), and DDT (all of which have been found on microplastics) could be problematic.

There is also concern of bioaccumulation of these contaminants as they move through the food chain, but little evidence that it does. There is also little research on the leaching of toxic products from these plastics and their impacts. In his recent publication on the status of water quality in Pensacola Bay, Dr. Mike Lewis agrees that more attention needs to be paid to microplastics.

These microfibers are from the inside of cigarette butts and a common form of microplastic in our waters.

Photo: Maia Mcguire

What Can We Do About the Microplastic Issue?

- Cut back on your use of plastics. Easier said than done, our world is full of plastic, but there are a few things you can do:

- a) choose not to use straws when eating out.

- b) purchase a good water bottle and take it with you. Many locations where we purchase coffee or fountain drinks you can use this bottle instead of their foam or plastic cups.

- Change your habits and product choices.

Personal care products with microplastics will have polyethylene on the ingredient label; if it does – choose a different one. There is a website that lists many of these products.

Http://householdproducts.nlm.nih.gov.

- If possible, wear clothing made of natural fibers.

Being aware of the microplastic problem is the first step in correcting it.

References

Unpublished data analyzed by the Escambia County Division of Marine Resources and Florida Sea Grant.

Yang, Y., I.A. Rodriguez-Jorquera, M. McGuire, G.S. Toor. 2015. Contaminants in the Urban Environment: Microplastics. Electronic Data Information Source (EDIS). 6 pages. http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/SS/SS64900.pdf.