by Rick O'Connor | Apr 25, 2025

Everyone has heard of sponges, and many know they grow in the ocean. But fewer are aware that sponges are actually animals. When we think of animals, we think of something that crawls around seeking food and laying eggs periodically. Sponges are not like that. They are “blob” looking creatures sitting on the ocean floor. At first glance you might call them fungi, or maybe some weird form of algae – but they are animals, the simplest form of animal life on the planet.

A vase sponge.

Florida Sea Grant

What makes them animals is the lack of cell walls and chlorophyll. Fungi also lack chlorophyll, but they do possess cell walls – so, are classified differently. Because animals lack chlorophyll they cannot produce their own food – and must consume creatures in order to obtain their needed sugars. So, what do sponges “hunt”? They feed on plankton in the water column – many of the microscopic creatures we have already written about in this series.

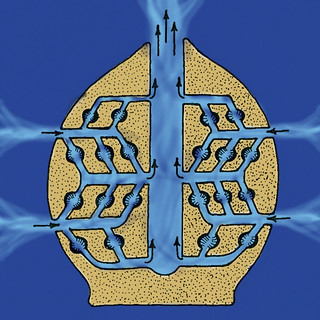

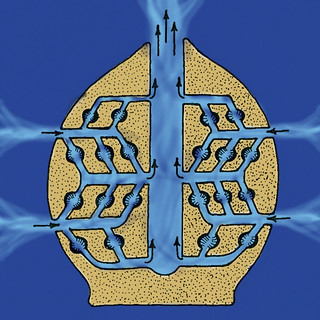

The sponge body is basically a colony of individual ameboid and flagellated cells. These small cells attach to the substrate and begin to reproduce sexually and asexually to form the colony. As they grow, they form a series of pores found on the exterior of the mass. The flagellated cells – called collar cells – move their flagella to generate a current. This current draws in seawater – along with its plankton – where the colony, both the flagellated and ameboid cells, feed. As the colony grows the exterior pores lead to channels and canals where the cells live and eventually empty into a larger cavity known as the atrium. Here the water moves upward and exits the sponge through an opening called the osculum. Waste from feeding exits the sponge through the osculum as well.

The anatomy of a sponge.

Flickr

As the colony grows it is supported by a series of tiny spike-like structures called spicules. Spicules are made of different materials and are one method of separating and classifying the different sponges. One group of sponges are known as the calcareous sponges – their spicules are made of calcium carbonate and are rough to the touch. Another group are known as the “glass” sponges – their spicules are made of silica and are sharp-prickly to the touch. A third group are known as the bath sponges – their spicules are made of a softer material called spongin. It is this third group that was used for centuries for both bathing and washing.

Glass sponges are beautiful.

Photo: NOAA

These simple creatures play an important role in the ecology of marine systems. As filter feeders, they remove material from the water column improving water clarity and quality. They remove excess nitrogen and play a role in the carbon cycle. They provide habitat for numerous small marine creatures where they can hide from predators and find food.

Sponges need a hard substrate to grow on and thus are more abundant in the coral reefs of south Florida. Locally I have only found them in the seagrass beds. But there they do play the same ecological role you would find them doing on coral reefs. They are one of the less encountered creatures of the northern Gulf.

by Rick O'Connor | Apr 11, 2025

Following the textbook I used when I was teaching environmental science there were 6.7 billion humans on the planet in 2011. I remember when we hit 6 billion. There was a lot made of it in the media. Currently (2025) we are at 8 billion. The textbook I used was published in 2011 – which means we have seen a growth of 2 billion people over 14 years – that’s a net gain of 143 million each year – 12 million each month – 400,000 a day – 17,000 an hour – 275 each minute – a net gain of 4 humans every second. Our population growth rate is astounding.

There are nearly 8 billion people on the planet today.

Photo: University of Central Florida

The calculation used to measure population change over time is relatively simple.

Population change = (births + immigration) – (deaths + emigration)

The natural history of creatures on our planet follows the same basic principle. There is a correlation between the number of offspring produced and the amount of parental care provided. The goal of each parent of any species is to have at least one of your offspring reach sexual maturity. Those who give very little parental care – trees, grasses, sea turtles, jellyfish, etc. – will produce large numbers of offspring knowing that over 90% will not make it – many will not make it past the first few days. Those who produce few offspring – songbirds, manatees, and gorillas – provide parental care to assure at least one makes it. Some will provide parental care for a few days, or a few weeks, others will provide it for a few years. BUT even those who show parental care typically produce 2-3 offspring knowing that a couple will not survive.

This nest of birds has three chicks. Not all will survive.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

This is a piece of the population control story. It does not benefit any species to have an overpopulation problem. I had to take an oral examination to complete my graduate degree. You are in a chair facing a long table full of professors who are asking you all sorts of questions. One question was “who is a rhinoceros’ greatest competitor?” Being very nervous I was bumbling and fumbling in my brain trying to figure WHO would be their biggest problem… and then – it came to me… another rhinoceros. They want the same space, the same resources, and the same mates as you. Competition begins day one. Over population is a problem for everyone. Other things that effect the number of newborns from reaching sexual maturity are predators and disease. In some species even the parents (typically the father) may be a predator – and will kill their own offspring (polar bears).

Placing humans in this model – we will see that typically there is only one offspring produced. Parents must do all they can to help this offspring reach sexual maturity. For Homo sapiens females reach sexual maturity between the ages of 8 and 13, 9 and 14 for males. In many cultures this is when the parent’s job is over and the child either enters an apprenticeship or gets married. Most cultures do not recognize “adulthood” until the age of 18. So… your job as a parent is to make sure they reach that age.

For most of our history environmental factors played a role in controlling population growth – namely disease. 200+ years ago, many children did not survive childbirth or died early from diseases. But things have changed.

It took from the time humans arrived on the planet to 1927 for us to reach 2 billion humans. It took less than 50 years to add the next 2 billion (1974), and only 25 years at add the next 2 billion (1999). The textbook I used stated we will reach 7 billion by 2012 – we reached it in 2011. They are expecting 9.7 billion by the year 2050.

What happened? What changed to create such a large exponential growth in the human population? The answer lies on both sides of the population change equation – more births are making it to puberty and less people are dying. Modern medicine has done miracles in improving overall human health on both ends – and this is wonderful news, but it does come with a cost. As with any species population – there is only so much space and resources. When the population of a species begins to stress this – many creatures will cease (or slow) reproduction. Another answer we see is dispersal – members of the population will move to new locations and build new populations reducing the stress on the resources. As we mentioned in a previous article – they will spread across the landscape until they reach a barrier that stops them from going further. But in nature the role of predators and disease has not gone away as it has with humans. The current growth rate for humans is 1.1% but has been slowly declining since the 1960s.

This brings up the question of carrying capacity (K) – the maximum number of individuals a population’s space and resources can support. As we mentioned, when K is reached in the natural world species either slow reproduction, disperse, or both. But what IS the carrying capacity for humans on this planet? The textbook I used mentioned there was no consensus on this. Some were saying as low as 2 billion – which we know was not accurate, though some would say some parts of the world are already in a population crisis. Others say it may be as high as 30 billion. A quick search on the internet finds the following…

- The AI response states somewhere between 9-10 billion.

- The Australian Academy of Science states it could be between 500 million and 1 trillion.

- The Population Connection states it is between 500 million and 1 sextillion (21 zeros).

Bottom line – we do not know – it depends on which model you use and how you view/term a functioning population. When I was teaching the class, most models stated somewhere between 10-15 billion.

As we mentioned, when you are reaching carrying capacity – most will either slow/stop reproduction or disperse. In our next article, we will look at how humans might address this problem.

References

Miller, G.T., Spoolman, S.E. 2011. Living in the Environment. Brooks/Cole Cengage Learning. Belmont CA. pp. 674.

Puberty and Precocious Puberty. Eunice Kennedy Shiver Institute of Child Health and Human Development. https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/puberty.

Population. United Nations. https://www.un.org/en/global-issues/population.

Human Population Growth. Libretexts. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Introductory_and_General_Biology/General_Biology_(Boundless)/45%3A_Population_and_Community_Ecology/45.04%3A_Human_Population_Growth/45.4A%3A_Human_Population_Growth.

How Many People Can the Earth Actually Support? Australian Academy of Science. https://www.science.org.au/curious/earth-environment/how-many-people-can-earth-actually-support.

What is the Carrying Capacity of Earth? The Population Connection. https://populationconnection.org/blog/carrying-capacity-earth/.

by Rick O'Connor | Apr 11, 2025

As we mentioned when we began writing about seaweed, seaweed and seagrass are very different. Seagrasses are true plants in the sense that they have an internal vascular system that runs water and other material throughout the plant. Like the artery and veins of animals – they are called xylem and phloem. Water in the soil is diffused through the tissue of the roots into the xylem, which moves the water up through the stem to the leave where it is used in photosynthesis. The sugars produced by photosynthesis are moved through back down into the plant by traveling through the phloem. Seagrasses produce small flowers that are pollinated by dispersing the pollen in the currents and by small invertebrates, such as amphipods and polychaetae worms. Seagrasses are true plants.

Grassbeds are also full of life, albeit small creatures.

Photo: Virginia Sea Grant

Believed to have originated as land plants, today there are about 72 species of seagrasses found around the world; seven are found in Florida; five found in the Pensacola Bay system. Though found in some open ocean systems, most seagrass beds are found in the protected waters of the estuary. They thrive in areas with low wave energy and clear water. They help stabilize the shoreline and remove pollutants from the water column. There is an abundance of marine creatures who use the seagrass beds as either a source of food, or habitat. It has been determined that at least 80% of the commercially important finfish and shellfish use seagrass beds for at least part of their life cycle.

Three of the five local species can be found in Santa Rosa Sound. Shoal grass (Halodule) has a flat blade but is very thin, between 2-3mm wide. Because it is so narrow, less surface area, it can tolerate waves better than turtle grass, and thus lives closer to the shoreline. Within the shoal grass you can find a variety of small baitfish feeding, as well as blue crabs and hermit crabs scavenging. But it does not provide the hiding spaces that the wider blade turtle grass does.

Shoal grass. One of the common seagrasses in Florida.

Photo: Leroy Creswell

Turtle grass (Thalassia) have blades that are 10mm wide. These wider blades do not handle the waves as well and thus turtle grass grows in deeper waters further off the beach. How deep they can grow is a function of the amount of sunlight reaching the bottom. In the Florida Keys turtle grass has been found at depths of 30 feet. Locally maximum depths are more likely near 10 feet. The wide blades of this grass provide surface area for a variety of small algae and invertebrates to attach. These epiphytes and epizoids are a major player in the food web of seagrass beds. Numerous invertebrates and fish feed on this “scum layer” found on the grass blades. The grazers attract low level predators such as pinfish, puffers, and sea horses. These in turn attract larger predators such as rays, speckled trout, and flounder. Manatees and sea turtles can be found here as well as sharks and the occasional bottled nose dolphin.

The wide blades of turtle grass provide habitat for a variety of epibiota.

Photo: UF IFAS

Manatee grass (Syringodium) resembles shoal grass, but the blade is round instead of flat. It can be found forming its own patches or dispersed within the other species. The abundance of this species seems to be increasing in local waters.

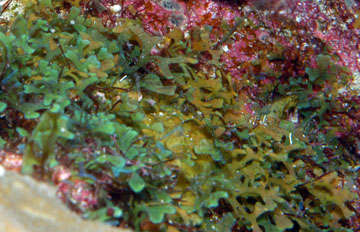

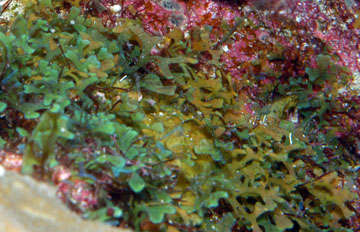

Gracilaria is a common epiphytic red algae growing in our seagrass beds. Photo: Rick O’Connor

Widgeon grass (Ruppia) is a common seagrass found in the upper portions of our estuary. Though it can live in the higher salinities near Pensacola Beach, it can also tolerate the lower salinities of the upper bays and thus, with less competition, does very well here. It also resembles shoal grass but differs in that the blade branches as it grows. Like all seagrass beds, widgeon grass can support a lot of marine creatures and increase the overall biodiversity of the bay.

The branched leaves of the widgeon grass.

Since the 1950s the northern Gulf coast has witnessed a decline in seagrass acreage. The decline was caused by a combination of factors. One, increased sedimentation with stormwater and development. In some cases, the seagrass was literally buried and in others the sediment decreased water clarity which decreased needed sunlight. Two, shrimp trawls. At one time shrimpers could pull their trawls through the grass to catch shrimp. This ripped and destroyed much of the habitat and the state closed shrimping in all grassbeds. Three, seawalls. Waves reflecting off the seawalls increased the wave energy within the Sound to a point that seagrass could not tolerate it. The landward edge of many grassbeds began to retreat from these seawalls reducing the overall acreage of the seagrass bed. Four, prop scars. Boats running through the grassbeds will cut deep scars in the grass that reach the sand beneath. It can take up to 10 years for the system to restore itself. And, with more boats out there, there are more scars. Five, the increase in the mass of drift algae settling on the grasses. These drift algae populations increase with increased nutrients being discharged into the Sound from land-based run-off. Drift algae cover the grasses decreasing their ability to absorb much needed sunlight.

Monitoring in recent years has shown that our seagrasses are trying to restore themselves and some beds have increased in size during the last couple of decades. Monitoring continues.

References

Florida Seagrass. Florida Department of Environmental Protection. https://floridadep.gov/rcp/seagrass.

Potouroglou, M., Pedder, K., Wood, K., Scalenghe. 2022. What to Know About Seagrass, the Ocean’s Overlooked Powerhouse. World Resources Institute. https://ocean.si.edu/ocean-life/plants-algae/seagrass-and-seagrass-beds#:~:text=Seagrasses%20produce%20the%20longest%20pollen,flower%20and%20fertilization%20takes%20place.

Seagrass and Seagrass Beds. Ocean, Find Your Blue. Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. https://ocean.si.edu/ocean-life/plants-algae/seagrass-and-seagrass-beds#:~:text=Seagrasses%20produce%20the%20longest%20pollen,flower%20and%20fertilization%20takes%20place..

Seagrass Species Profiles. South Florida Aquatic Environments. Florida Museum of Natural History. https://floridadep.gov/rcp/seagrass.

by Rick O'Connor | Mar 28, 2025

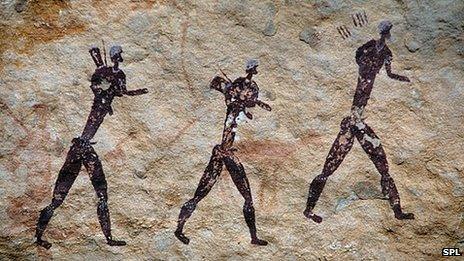

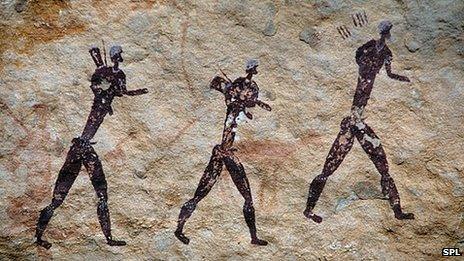

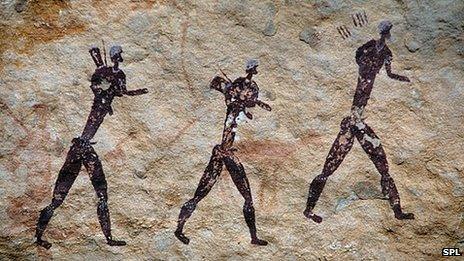

Evidence suggests that Homo sapiens’ initial population originated in east Africa – though some think we may have originated in southern Africa, and others from northwest Africa. It is believed this occurred about 300,000 years ago. The first humans were hunter gathers and fed primarily on small prey and plants – we are omnivorous. With the development of stone tools early humans could feed on larger prey and take a different position in the food chain.

Evidence suggest that humans originated in Africa and began their dispersal across the planet from there.

Image: BBC.

Populations of all creatures increase and decrease due to the number of births, deaths, immigration, and emigration within their populations (we will focus more on the human population in the next article). As populations grow, competition for needed resources increases. One response to this competition is dispersal – the movement of members of a population to a new location where resources can be found. This is different than migration in that in dispersal the members do not return – they have moved away.

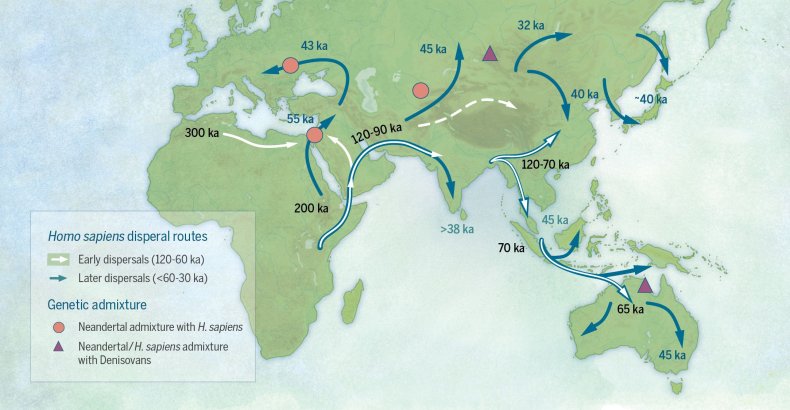

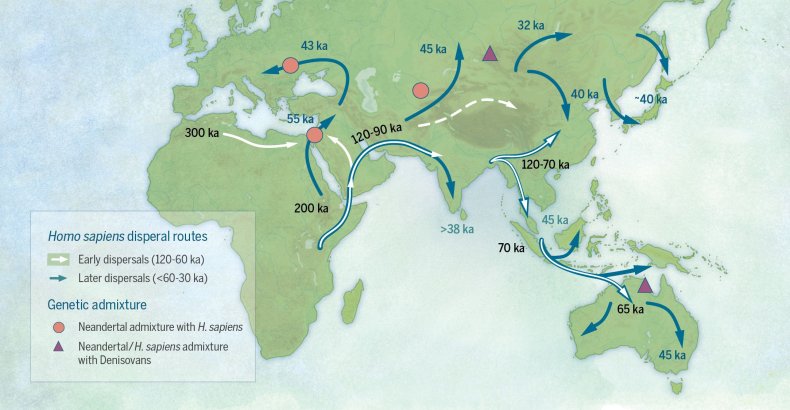

Evidence suggests that humans began dispersing from Africa very early. It was thought at first humans did move into southern Africa, but there was a mass movement north into the Middle East. From here humans began to move east along southern Asia to India and beyond to southeast Asia. There is evidence of “island hopping” as they made their way across Indonesia and eventually to Australia. Later groups from southern Asia dispersed north into northern Asia. From here there were two movements – one into Europe and another across an exposed landmass connecting Asia to North America – remember the Earth continues to go through slow change over time. At one time there was a land bridge that connected the two continents and allowed humans, and other species, to cross. Humans began to spread across North America and – with the emergence of a land bridge in Central America – reached South America. There are those who also believe – based on language and culture – some Polynesian humans reached South America by boat. To test this idea an expedition sailed from Polynesia to South America on a balsa wood raft called Kon Tiki in the 1940s. This same team attempted to sail from Africa to South America to show this could have been a dispersal route as well using boat materials from that time – but that expedition failed. However they reached South America, they did – and humans had dispersed to cover all landmasses except Antarctica. This still holds true – there are no native populations of humans on the Antarctic continent – only visitors.

This shows possible dispersal routes of humans out of Africa.

Image: Newsweek.

Within each region of the planet where humans have inhabited, we find physical and cultural differences. The physical difference – which we call races today – were adaptations to the environment where they lived. There languages, tools and building practices, songs and instruments, and religions were all born from the area where they lived. Many of these populations were isolated from each other – and so their cultures became quite different. As these populations grew and expanded, they would come in contact with each other. Many times, these different cultures, or tribes, would fight for resources and space. As our imaginations and technologies grew, some cultures were able to cover more territory and conflicts increased.

Today there are about 8 billion humans on the planet. Some areas are more densely populated than others. Based on the website Worldometer – we are gaining a new human almost every second.

Over history, most species have had a slower population growth – if growing at all. Numbers are kept under control by predators, disease, and environmental conditions that impede, or restrict, reproduction. But not with humans. In the next article we will look closer at the cause of the human population explosion.

References

Pavid, K. 2018. Rethinking Our Human Origins in Africa. Science News. Natural History Museum. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/news/2018/july/the-way-we-think-about-the-first-modern-humans-in-africa.html.

Pobinar, B. 2013. Evidence for Meat-eating by Early Humans. Nature Education Knowledge. (46)1. https://www.nature.com/scitable/knowledge/library/evidence-for-meat-eating-by-early-humans-103874273/#:~:text=Tooth%20morphology%20and%20dental%20microwear,Ungar%202000%3B%20Luca%20et%20al..

Dorey, F., Blaxland, B. 2020. The First Migrants Out of Africa. Australian Museum. https://australian.museum/learn/science/human-evolution/the-first-migrations-out-of-africa/.

Kon Tiki Expedition. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kon-Tiki_expedition.

Worldometer. https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/.

by Rick O'Connor | Mar 14, 2025

If green algae are difficult to find in the northern Gulf because most prefer freshwater, and rocky shorelines, brown are difficult because the group prefers colder water, as well as rocky shorelines – but we do have some here.

Brown algae get their color because the ratio of photosynthetic pigments in their cells favors the xanthophylls – which produces a yellow-brown color. Like most macroscopic algae, they attach to the hard bottom using a holdfast and then extend their stipe and blade into the water column to absorb light. One group of brown algae are the largest of all seaweeds, the giant kelp Macrocystis. In the nutrient rich waters off California this seaweed will grow up to one foot a day and can reach heights of up to 175 feet tall. Since seaweeds do not possess true stems, or any wood, what holds this giant seaweed up are air filled bladders called pneumatocysts – structures found on other brown algae and are unique to the group.

The largest, fastest growing seaweed – giant kelp.

Photo: NOAA

Many species are popular with seafood dishes, such as Nori. Others produce a carbohydrate known as algin that is extracted and used as a food additive. You may have heard “ice cream has seaweed in it”. What it actually has is algin. This carbohydrate acts as a smoothing agent for products. Solids should be solid – like frozen ice cream – but, as you know, we do not want our ice cream solid. So, for a period of time, the algin keeps the ice cream smooth and creamy. Algin is used in toothpaste, lipstick, and icing on cakes for the same reason.

But along the northern Gulf coast, brown algae are not common. Despite preferring marine waters, they do prefer colder water and, like most seaweeds, need a hard substrate to attach their holdfast. But by exploring our local rock jetties and seawalls we do find some. One in particular is the common rock weed – Dictyota. This sessile seaweed branches out and resembles small trees. But the most common, and most recognized brown algae on our coast is Sargassum.

The brown algae Dictyota.

Photo: NOAA

Sargassum has found a way to deal with an environment where little hard bottom is present. Using the characteristic air bladders allows it to float at the surface to absorb the much needed sunlight. Because of this ability to float, Sargassum can be found all across the oceans, and often form large mats that cover miles of open sea and extend several feet down. It actually creates a whole new ecosystem in the middle of the sea. The major ocean currents rotate like a hurricane and, like a hurricane, the center – the “eye” – is calm. Within this calm huge mats of Sargassum collect. The ancient sailors called the center of the Atlantic Ocean the “Sargasso Sea”. But as the large currents spin, sections of this large mat “spin off” and are pushed across the ocean. Much of it heads towards Florida, the Gulf, and eventually to the northern Gulf.

If you grab a mask and snorkel and swim within the Sargassum before it reaches the waves, you will encounter a whole community of creatures that live here. Sargassum crabs, Sargassum fish, and even seahorses live within it. There are shrimps, worms, and even mollusks. When baby sea turtles head offshore after hatching, many seek out these Sargassum mats to both hide in, and feed within. They will spend their youth here before returning back to shore for different prey.

However, once many of these creatures sense the waves breaking, and now the mat is about to wash ashore, they will move to mats further offshore. That said, picking through the Sargassum on the beach may still yield some interesting creatures.

Sargassum.

In recent years the amount of Sargassum washing ashore has increased and become problematic – particularly in southeast Florida and the Florida Keys. At times, mounds three feet high have been found. Those communities are working on methods to deal with the problem. But here locally, these mats are a new world to explore.

References

Giant Kelp. Monterey Bay Aquarium. https://www.montereybayaquarium.org/animals/animals-a-to-z/giant-kelp.