by Carrie Stevenson | Aug 25, 2017

Life on the Gulf Coast can be beautiful, but has its share of complications. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

Life on the coast has tremendous benefits; steady sea breezes, gorgeous beaches, plentiful fishing and paddling opportunities. Nevertheless, there are definite downsides to living along it, too. Besides storms like Hurricane Harvey making semi-regular appearances, our proximity to the water can make us more vulnerable to flooding and waterborne hazards ranging from bacteria to jellyfish. One year-round problem for those living directly on a shoreline is erosion. Causes for shoreline erosion are wide-ranging; heavy boat traffic, foot traffic, storms, lack of vegetation with anchoring roots, and sea level rise.

Many homeowners experiencing loss of property due to erosion unwittingly contribute to it by installing seawalls. When incoming waves hit the hard surface of the wall, energy reflects back and moves down the coast. Often, an adjacent homeowner will experience increased erosion and bank scouring after a neighboring property installs a seawall. This will often lead that neighbor to install a seawall themselves, transferring the problem further.

Erosion can damage root systems of shoreline trees and grasses. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

Currently, south Louisiana is experiencing significant coastal erosion and wetlands losses. The problem is compounded by several factors, including canals dredged by oil companies, which damage and break up large patches of the marsh. Subsidence, in which the land is literally sinking under the sea, is happening due to a reduced load of sediment coming down the Mississippi River. Sea level rise has contributed to erosion, and most recently, an invasive insect has caused large-scale death of over 100,000 acres of Roseau cane (Phragmites australis). Add the residual impacts from the oil spill, and you can understand the complexity of the situation.

Luckily, there are ways to address coastal erosion, on both the small and large scale. On Gulf and Atlantic beaches, numerous coastal communities have invested millions in beach renourishment, in which offshore sand is barged to the coast to lengthen and deepen beaches. This practice, while common, can be controversial because of the cost and risk of beaches washing out during storms and regular tides. However, as long as tourism is the #1 economic driver in the state, the return on investment seems to be worth it.

On quieter waters like bays and bayous, living shorelines have “taken root” as a popular method of restoring property and stabilizing shorelines. This involves planting marsh grasses along a sandy shore, often with oyster or rock breakwaters placed waterward to slow down wave energy, and allow newly planted grasses to take root.

Locally in Bayou Grande, a group of neighbors were experiencing shoreline erosion. Over a span of 50 years, the property owners used a patchwork of legally installed seawalls, bulkheads, rip rap piles, private boat ramps, piers, mooring poles and just about anything else one can imagine, to reduce the problem. Over time, the seawalls and bulkheads failed, lowering the property value of the very property they were meant to protect and increasing noticeable physical damage to the adjacent properties.”

Project Greenshores is a large-scale living shoreline project in Pensacola. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

In 2011, a group of neighboring property owners along the bayou decided to take action. After considering many repair options, the neighbors decided to pursue a living shoreline based on aesthetics, long-term viability, installation cost, maintenance cost, storm damage mitigation and feasibility of installation. By 2017, the living shoreline was constructed. Oyster shell piles were placed to slow down wave energy as it approached the transition zone from the long fetch across the bayou, while uplands damage was repaired and native marsh grasses and uplands plants were restored to slow down freshwater as it flowed towards the bayou. Sand is now accruing as opposed to eroding along the shoreline. Wading shorebirds are now a constant companion and live oysters are appearing along the entire 1,200-foot length. Additionally the living shoreline solution provided access to resources, volunteer help, and property owner sweat equity opportunities that otherwise would have been unavailable. An attribute that has surprisingly appeared – waterfront property owners are now able to keep their nicely manicured lawns down to within 30 feet of the water’s edge. At that point, the landscape immediately switches back to native marsh plants, which creates a quite robust and attractive intersection. (Text and information courtesy Charles Lurton).

Successes like these all over the state have led the Florida Master Naturalist Program to offer a new special topics course on “Coastal Shoreline Restoration” which provides training in the restoration of living shorelines, oyster reefs, mangroves, and salt marsh, with focus on ecology, benefits, methods, and monitoring techniques. Keep an eye out for this course being offered near you. If you are curious about living shorelines and want to know more, reach out to the Florida Department of Environmental Protection Ecosystem Restoration section for help and read through this online document.

by Laura Tiu | Jun 3, 2017

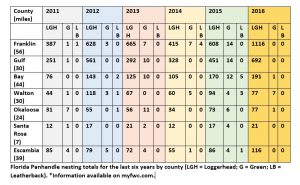

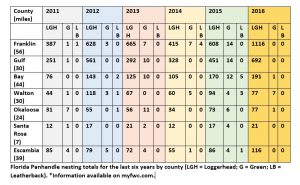

There are five species of sea turtles that nest from May through October on Florida beaches. The loggerhead, the green turtle and the leatherback all nest regularly in the Panhandle, with the loggerhead being the most frequent visitor. Two other species, the hawksbill and Kemp’s Ridley nest infrequently. All five species are listed as either threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act.

Due to their threatened and endangered status, the Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission/Fish and Wildlife Research Institute monitors sea turtle nesting activity on an annual basis. They conduct surveys using a network of permit holders specially trained to collect this type of information. Managers then use the results to identify important nesting sites, provide enhanced protection and minimize the impacts of human activities.

Statewide, approximately 215 beaches are surveyed annually, representing about 825 miles. From 2011 to 2015, an average of 106,625 sea turtle nests (all species combined) were recorded annually on these monitored beaches. This is not a true reflection of all of the sea turtle nests each year in Florida, as it doesn’t cover every beach, but it gives a good indication of nesting trends and distribution of species.

If you want to see a sea turtle in the Florida Panhandle, please visit one of the state-permitted captive sea turtle facilities listed below, admission fees may be charged. Please call the number listed for more information.

If you want to see a sea turtle in the Florida Panhandle, please visit one of the state-permitted captive sea turtle facilities listed below, admission fees may be charged. Please call the number listed for more information.

- Gulf Specimen Marine Laboratory, 222 Clark Dr, Panacea, FL 32346 850-984-5297 Admission Fee

- Gulf World Marine Park, 15412 Front Beach Rd, Panama City, FL 32413 850-234-5271 Admission Fee

- Gulfarium Marine Adventure Park, 1010 Miracle Strip Parkway SE, Fort Walton Beach, FL 32548 850-243-9046 or 800-247-8575 Admission Fee

- Navarre Beach Sea Turtle Center, 8740 Gulf Blvd, Navarre, FL 32566 850-499-6774

To watch a female loggerhead turtle nest on the beach, please join a permitted public turtle watch. During sea turtle nesting season, The Emerald Coast CVB/Okaloosa County Tourist Development Council offers Nighttime Educational Beach Walks. The walks are part of an effort to protect the sea turtle populations along the Emerald Coast, increase ecotourism in the area and provide additional family-friendly activities. For more information or to sign up, please email ECTurtleWatch@gmail.com. An event page may also be found on the Emerald Coast CVB’s Facebook page: facebook.com/FloridasEmeraldCoast.

by Laura Tiu | Apr 14, 2017

It was disheartening to read that even with double red flags flying, 22 people had to be recused from the Gulf near Destin, FL recently, and one person lost their life. In that spirit, I believe it is important to review information on the importance of respecting our sometimes-unforgiving gulf.

First of all, stay calm.

Photo By: Laura Tiu

Swimmers getting caught in rip currents make up the majority of lifeguard rescues. These tips from Florida Sea Grant and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Weather Service (NWS) can help you know what to do if you encounter a rip current.

What Are Rip Currents?

Rip currents are formed when water flows away from the shore in a channeled current. They may form in a break in a sandbar near the shore, or where the current is diverted by a pier or jetty.

From the shore, you can look for these clues in the water:

- A channel of choppy water.

- A difference in water color.

- A line of foam, seaweed, or debris moving out to sea.

- A break in incoming wave patterns.

If you get caught in a rip current, don’t panic! Stay calm and do not fight the current. Escape the current by swimming across it–parallel to shore–until you are out of the current. When you get out of it, swim back to the shore at an angle away from the current. If you can’t break out of the current, float or tread water until the current weakens. Then swim back to shore at an angle away from the rip current. Rip currents are powerful enough to pull even experienced swimmers away from the shore. Do not try to swim straight back to the shore against the current.

Tips for Swimming Safely

You can swim safely this summer by keeping in mind some simple rules. Many people have harmed themselves trying to rescue rip current victims, so follow these steps to help someone stuck in a rip current. Get help from a lifeguard. If a lifeguard is not present, yell instructions to the swimmer from the shore and call 9-1-1. If you are a swimmer caught in a rip current and need help, draw attention to yourself–face the shore and call or wave for help.

Photo by: Laura Tiu

How Do I Escape a Rip Current?

- Rip currents pull people away from shore, not under the water. Rip currents are not “undertows” or “rip tides.”

- Do not overestimate your swimming abilities. Be cautious at all times.

- Never swim alone.

- Swim near a lifeguard for maximum safety.

- Obey all instructions and warnings from lifeguards and signs.

- If in doubt, don’t go out!

Adapted and excerpted from: “Rip Currents” Florida Sea Grant

The Foundation for the Gator Nation, An Equal Opportunity Institution.

by Will Sheftall | Jul 22, 2016

Birds, migration, and climate change. Mix them all together and intuitively, we can imagine an ecological train wreck in the making. Many migratory bird species have seen their numbers plummet over the past half-century – due not to climate change, but to habitat loss in the places they frequent as part of their jet-setting life history.

Migrating songbirds forage for insects in coastal scrub-shrub habitat. Photo credit: Erik Lovestrand, UF IFAS Extension

Now come climate simulation models forecasting more change to come. It will impact the strands of places migrants use as critical habitat. Critical because severe alteration of even one place in a strand can doom a migratory species to failure at completing its life cycle. So what aspect of climate change is now threatening these places, on top of habitat alteration by humans?

It’s the change in weather patterns and sea level that we’re already beginning to see, as the impacts of global warming on Earth’s ocean-atmosphere linkage shift our planetary climate system into higher gear.

For migratory birds, the journey itself is the most perilous link in the life history chain. A migratory songbird is up to 15 times more likely to die in migration than on its wintering or breeding grounds. Headwinds and storms can deplete its energy reserves. Stopover sites for resting and feeding are critical. And here’s where the Big Bend region of Florida figures prominently in the life history of many migratory birds.

According to a study published in March of this year (Lester et al., 2016), field research on St. George Island documented 57 transient species foraging there as they were migrating through in the spring. That number compares favorably with the number of species known to use similar habitat at stopover sites in Mississippi (East Ship Island, Horn Island) as well as other central and western Gulf Coast sites in Alabama, Louisiana, and Texas.

We now can point to published empirical evidence that the eastern Gulf Coast migratory route is used by as many species as other Gulf routes to our west. This confirmation makes conservation of our Big Bend stopover habitat all the more relevant.

The authors of the study observed 711 birds using high-canopy forest and scrub/shrub habitat on St. George Island. Birds were seeking energy replenishment from protein-rich insects, which were reported to be more abundant in those habitats than on primary dunes, or in freshwater marshes and meadows.

So now we know that specific places on our barrier islands that still harbor forests and scrub/shrub habitat are crucial. On privately-owned island property, prime foraging habitat may have been reduced to low-elevation mixed forest that is often too low and wet to be turned into dense clusters of beach houses.

Coastal slash pine forest is vulnerable to sea level rise. Photo credit: Erik Lovestrand, UF IFAS Extension

Think tall slash pines and mid-story oaks slightly ‘upslope’ of marsh and transitional meadow, but ‘downslope’ of the dune scrub that is often cleared for development.

“OK, I get it,” you say. “It’s as if restaurant seating has been reduced and the kitchen staff laid off. Somebody’s not going to get served.” Destruction of forested habitat on our Gulf Coast islands has significantly reduced the amount of critical stopover habitat for birds weary from flying up to 620 miles across the Gulf of Mexico since their last bite to eat.

But why the concern with climate change on top of this familiar story of coastal habitat lost to development? After all, we have conservation lands with natural habitat on St. Vincent, Little St. George, the east end of St. George, and parts of Dog Island and Alligator Point. Shouldn’t these islands be able to withstand the impacts of stronger and/or more frequent coastal storms, and higher seas – and their forested habitat still serve the stopover needs of migratory birds?

Let’s revisit the “low and wet” part of the equation. Coastal forested habitat that’s low and wet – either protected by conservation or too wet to be developed – is in the bull’s eye of sea level rise (SLR), and sooner rather than later.

Using what Lester et al. chose as a reasonably probable scenario within the range of SLR projections for this century – 32 inches, these low-elevation forests and associated freshwater marshes would shrink in extent by 45% before 2100. It could be less; it could be more. Conditions projected for a future date are usually expressed as probable ranges. Experience has proven them too conservative in some cases.

The year 2100 seems far away…but that’s when our kids or grandkids can hope to be enjoying retirement at the beach house we left them. Hmm.

Scientists CAN project with certainty that by the time SLR reaches two meters (six and a half feet) – in whatever future year that occurs, 98% of “low and wet” forested habitat will have transitioned to marsh, and then eroded to tidal flat.

But before we spool out the coming years to a future reality of SLR that has radically changed the coastline we knew, let’s consider where the crucial forested habitat might remain on the barrier islands of the next generation’s retirement years:

It could remain in the higher-elevation yard of your beach house, perhaps, if you saved what remnant of native habitat you could when building it. Or if you landscaped with native trees and shrubs, to restore a patch of natural habitat in your beach house yard.

Migratory songbird stopover habitat saved during beach house construction. Photo credit: Erik Lovestrand, UF IFAS Extension

We’ve all thought that doing these things must be important, but only now is it becoming clear just how important. Who would have thought, “My beach house yard: the island’s last foraging refuge for migratory songbirds!” even in our most apocalyptic imagination?

But what about coastal mainland habitat?

The authors of the March 2016 St. George Island study conclude that, “…adjacent inland forested habitats must be protected from development to increase the probability that forested stopover habitat will be available for migrants despite SLR.” Jim Cox with Tall Timbers Research Station says that, “birds stop at the first point of land they find under unfavorable weather conditions, but also continue to migrate inland when conditions are favorable.”

Migratory birds are fortunate that the St. Marks Refuge protects inland forested habitat just beyond coastal marshland. A longer flight will take them to the leading edge of salty tidal reach. There the beautifully sinuous forest edge lies up against the marsh. This edge – this trailing edge of inland forest – will succumb to tomorrow’s rising seas, however.

Sea level rise will convert coastal slash pine forest to salt marsh. Photo credit: Erik Lovestrand, UF IFAS Extension

As the salt boundary moves relentlessly inland, it will run through the Refuge’s coastal buffer of public lands, and eventually knock on the surveyor’s boundary with private lands. All the while adding flight miles to the migration journey.

In today’s climate, migrants exhausted from bucking adverse weather conditions over the Gulf may not have enough energy to fly farther inland in search of forested foraging habitat. Will tomorrow’s climate make adverse Gulf weather more prevalent, and migration more arduous?

Spring migration weather over the Gulf can be expected to change as ocean waters warm and more water vapor is held in a warmer atmosphere. But HOW it will change is difficult to model. Any specific, predictable change to the variability of weather patterns during spring migration is therefore much less certain than SLR.

What will await exhausted and hungry migrants in future decades? Our community decisions about land use should consider this question. Likewise, our personal decisions about private land management – including beach house landscaping. And it’s not too early to begin.

Erik Lovestrand, Sea Grant Agent and County Extension Director in Franklin County, co-authored this article.

by Laura Tiu | May 8, 2016

Florida has the highest number of sea turtles of any state in the continental US. Three species are common here including loggerhead, green and leatherback turtles. The Federal Endangered Species Act lists all of sea turtles in Florida as either threatened or endangered.

Sea turtle nesting season for the area began May 1, 2016. Adult females only nest every 2-3 years. At 20-35 years old, adult loggerhead and green female turtles return to the beach of their birth to nest. At this age, they are about 3 feet long and 250-300 pounds. The turtles will lay their eggs from May – September, with 50-150 baby turtles hatching after 45-60 days, usually at night. One female may nest several times in one season.

If you happen to see a sea turtle nesting, or nest hatching, stay very quiet, keep your distance, and turn any lights off (no flash photography). You should never try to touch a wild sea turtle. Also, do not touch or move any hatchlings. The small turtles need to crawl on the beach in order to imprint their birth beach on their memory.

During nesting season, it is important to keep the beaches Clean, Dark and Flat. Clean, by removing everything you brought to the beach including trash, food, chairs and toys; dark, by keeping lights off, using sea turtle friendly lighting and red LED flashlights if necessary; and flat, filling up all holes and knocking down sand castles before leaving the beach. If you see anyone harassing a sea turtle or a sea turtle in distress for any reason, do not hesitate to call the Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission hotline at 1-888-404-3922.

There has been encouraging sea turtle news in Florida as a result of the conservation actions being undertaken. There is an increasing number of green turtle nests and a decreasing number of dead turtles found on beaches.

If you want to see a sea turtle and learn more about these fascinating creatures, visit the Navarre Beach Sea Turtle Conservation Center, Navarre, FL, the Gulfarium Marine Adventure Park on Okaloosa Island, Fort Walton Beach, FL, or Gulf World Marine Park in Panama City, FL.

| County |

Beach nesting area (miles) |

Number of loggerhead sea turtle nests |

Number of green sea turtle nests |

Number of leatherback sea turtle nests |

| Franklin |

56 |

608 |

14 |

0 |

| Gulf |

29 |

451 |

14 |

0 |

| Bay |

44 |

170 |

12 |

5 |

| Walton |

30 |

94 |

4 |

3 |

| Okaloosa |

24 |

73 |

6 |

0 |

| Santa Rosa |

7 |

17 |

4 |

0 |

| Escambia |

39 |

86 |

4 |

1 |

Table 1: Data from the 2015 Florida Statewide Nesting Beach Survey available at: www.myfwc.com.

Young loggerhead sea turtle heading for the Gulf of Mexico. Photo: Molly O’Connor

The Foundation for the Gator Nation, An Equal Opportunity Institution.

by Laura Tiu | Apr 22, 2016

The Deepwater Horizon (DWH) oil spill occurred about 50 miles offshore of Louisiana in April 2010. Approximately 172 million gallons of oil entered the Gulf of Mexico. Five years after the incident, locals and tourists still have questions. This article addresses the five most common questions.

QUESTION #1: Is Gulf seafood safe to eat?

Ongoing monitoring has shown that Gulf seafood harvested from waters that are open to fishing is safe to eat. Over 22,000 seafood samples have been tested and not a single sample came back with levels above the level of concern. Testing continues today.

QUESTION #2: What are the impacts to wildlife?

This question is difficult to answer as the Gulf of Mexico is a complex ecosystem with many different species — from bacteria, fish, oysters, to whales, turtles, and birds. While oil affected individuals of some fish in the lab, scientists have not found that the spill impacted whole fish populations or communities in the wild. Some fish species populations declined, but eventually rebounded. The oil spill did affect at least one non-fish population, resulting in a mass die-off of bottlenose dolphins. Scientists continue to study fish populations to determine the long term impact of the spill.

Question #3: What cleanup techniques were used, and how were they implemented?

Several different methods were used to remove the oil. Offshore, oil was removed using skimmers, devices used for removing oil from the sea’s surface before it reaches the coastline. Controlled burns were also used, where surface oil was removed by surrounding it with fireproof booms and burning it. Chemical dispersants were used to break up the oil at the surface and below the surface. Shoreline cleanup on beaches involved sifting sand and removing tarballs and mats by hand.

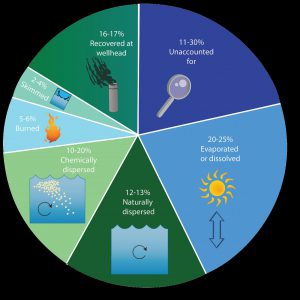

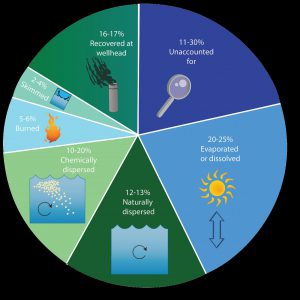

QUESTION #4: Where did the oil go and where is it now?

The oil spill covered 29,000 square miles, approximately 4.7% of the Gulf of Mexico’s surface. During and after the spill, oil mixed with Gulf of Mexico waters and made its way into some coastal and deep-sea sediments. Oil moved with the ocean currents along the coast of Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida. Recent studies show that about 3-5% of the unaccounted oil has made its way onto the seafloor.

QUESTION #5: Do dispersants make it unsafe to swim in the water?

The dispersant used on the spill was a product called Corexit, with doctyl sodium sulfosuccinate (DOSS) as a primary ingredient. Corexit is a concern as exposure to high levels can cause respiratory problems and skin irritation. To evaluate the risk, scientists collected water from more than 26 sites. The highest level of DOSS detected was 425 times lower than the levels of DOSS known to cause harm to humans.

For additional information and publications related to the oil spill please visit: https://gulfseagrant.wordpress.com/oilspilloutreach/

Adapted From:

Maung-Douglass, E., Wilson, M., Graham, L., Hale, C., Sempier, S., and Swann, L. (2015). Oil Spill Science: Top 5 Frequently Asked Questions about the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. GOMSG-G-15-002.

An estimate of what happened to approximately 200 million gallons oil from the DWH oil spill. Data from Lehr, 2014. (Florida Sea Grant/Anna Hinkeldey)

The Foundation for the Gator Nation, An Equal Opportunity Institution.