by Rick O'Connor | Jun 28, 2019

The recent attacks on swimmers in North Carolina have once again brought up the topic of sharks. And of course, “Shark Week” is coming up. It is understandable why people are concerned about swimming in waters were animals weighing several hundred pounds with rows of sharp, sometimes serrated, teeth are lurking. It is also understandable that local tourism groups are concerned that visitors are concerned. Sounds like the movie Jaws all over again.

The Bull Shark is considered one of the more dangerous sharks in the Gulf. This fish can enter freshwater but rarely swims far upstream. Photo: Florida Sea Grant

So, what is the risk?

It is good question to ask for anything we feel uncomfortable with. Hiking in Rockies where bears might roam. Hiking in wetlands of Florida or deserts of the American southwest where venomous snakes may lurk. Paddling the creeks and rivers of the American southeast where alligators could be basking. All are concerns.

According to G. Tyler Miller and Scott E. Spoolman, a risk is the probability of suffering harm from a hazard that can cause injury, disease, death, economic loss, or damage. There is a difference between possibility and probability. There is always the possibility of a shark attack, but what is the probability it will happen? Unfortunately, media blast can create a scare over a highly unlikely possibility without discussing the data driven probability of it happening. We all take risk every day – riding in a car, smoking, drinking alcohol, eating bad food – which can lead to heart issues and the number one killer of humans worldwide, and more. Many of these we do not consider risky. We feel we are in control, understand the risk, and are managing from them. Those risk we have little control over – shark attacks – seem more of a risk than they really are. The car is far more dangerous, yet we do not hesitate to get in one at zoom onto the interstate.

Let’s conduct a simple risk assessment of shark attacks…

What is the hazard of concern?

Being attacked by a shark

Dying from the shark attack

How likely is the event?

The International Shark Attack File was first developed after World War II to address the issue of shark attacks on US Navy personnel, but expended to everyone. It was originally housed at the Smithsonian Institute but is currently housed at the Florida Museum of Natural History in Gainesville. Based on their records of unprovoked shark attacks (the ones we are truly interested in) there have been 3103 attacks on humans since 1580. 46% of those were in the United States, ranking us #1. Number two and three are Australia and South Africa. So as far as nations go, we are number one for attacks. However, this equates to 7 attacks / year – worldwide. And not all of those died. Most did not.

Which state?

Since 1837, 828 attacks (57%) occurred in Florida. This equates to 4.5 attacks / year. Florida is number one, followed by Hawaii and California.

What about counties in Florida?

Since 1882 there have been 303 attacks (36%) in Volusia County. This equates to 2.2 attacks/year. The total number of attacks in Florida panhandle counties since 1882 have been 25 – this is 0.2 attacks/year for the entire panhandle.

What were these Floridians and visitors doing when they were attacked?

Surface recreation (surfing, boogie boarding), swimming, and wading top the list, the other activities were logged.

So, there have between 8-10 shark attacks each year, and two fatalities, worldwide.

The white shark is responsible for more attacks on humans than any other species. It is found in the Gulf of Mexico in the winter months but there are no reports of attacks in Florida.

Photo courtesy of UF IFAS

The Risk Assessment is used to develop a Risk Management Plan

First, How do these shark attack data compare with other risks?

I wondered how many car accidents occur each year worldwide?

According to USA Insurance Coverage, who got their data from the National Highway Traffic Administration – 5,250,000 each year in the United States alone. About one every 60 seconds.

Situations that cause human deaths annually in the United States

Heart disease 652,486 1 in 5 people

Cancer 553,888 1 in 7

Stroke 150,074 1 in 24

Shark attack 1 1 in 3,748,067

Between 1992-2000 there were 2 shark attacks in Florida. In that same time period, there were 135 drownings.

Between 2004 and 2013, 361 people drowned in rip currents. During that same period, 8 people were attacked by sharks.

Between 1990 and 2009, in Florida, 112,581 people were involved in bicycle accidents; 2272 died. In that same period, there were 435 shark attacks in Florida; 4 died.

And my favorite…

Between 1984 and 1987, 6339 people had to visit a hospital in New York City because they were bitten by a human. This was 1585 / year. In that same period there were 45 shark attacks in the entire United States. This was 11 / year.

Second, How should we reduce the risk of shark attack?

Well… as you can see from the assessment and comparative risk analysis, many would say you did not need to develop a plan to reduce risk because the risk is too low to fool with. You should spend time on hazards that are of a more real concern. That said, there are some things you can do.

– Avoid excessive splashing; it is known that sharks are attracted to this. It is also known that more often than not, they move away when they detect the source of the splashing.

– Avoid swimming when bleeding or in water with strong smells (like fish bait); this too will attract them.

– Most unprovoked attacks occur between 11:00 AM and 3:00 PM. But honestly, that is when most people are in the water. This could be different if most of us swim after sunset. That said, we recommend that you reduce swimming at dawn and dusk.

I hope this clear up some of the concerns about shark attacks. Yes, they do happen – but infrequently. There are some things you can do to reduce your risk, but these should not keep you from enjoying water related activities. Enjoy your time here on the Gulf coast. Be careful driving and try to eat healthier.

References

International Shark Attack File. https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/shark-attacks/.

Miller, G.T., S.E. Spoolman. 2011. Living in the Environment. 16th Edition. Brooks and Cole, Cengage Learning. Belmont CA. pp. 121.

USA Insurance. https://www.usacoverage.com/auto-insurance/how-many-driving-accidents-occur-each-year.html.

by Scott Jackson | Mar 29, 2019

Boats at a calm rest in Massalina Bayou, Bay County, Florida.

Wow! I was so excited to hear the news. Dad had just called to invite me on a deep sea trip out of Galveston. I had grown up fishing but had never been to sea. My mind raced – surely the fish would be bigger than any bass or catfish we ever caught. I day dreamed for a few moments of being in the newspaper with the headline, “Local Teen Catches World Record Red Snapper”.

It seemed more like a Christmas Morning when dad woke me up for our 100-mile car trip to the coast. We hurried to breakfast just a few hours before sunrise. I had the best fluffy pancakes with a lot of syrup, washed down with coffee with extra cream and sugar. I was wide awake and ready for the fishing adventure of a lifetime!

The crew welcomed us all aboard and helped us settle in. Dad was still tired and went to nap below deck. I was outside taking in all the sights of a busy head boat, including the smell of diesel fuel, bait, and dressed fish. About an hour into my great fishing adventure things started to change. I grew queasy and tired. I went to find my dad and he was already sick. I looked at him and then turned around to go out the ship’s door. My eyes saw the horizon twist sideways and my brain said “WRONG!!!” – this was my first encounter with seasickness.

The crew quickly moved both of us back outside. I was issued a pair of elastic pressure wristbands – the elastic holds a small ball into the underside of your wrist. The attention and sympathy might have made me feel a little better but there was really no recovery until we got back into the bay an excruciating 6 hours later. There were no headlines to write this day, only the chance to watch others catch fish while my stomach and head churned – often in opposite directions.

Fast forward to today, decades later. I often make trips into Gulf to help deploy artificial reefs without any problems with motion sickness. Some of my success in avoiding seasickness are lessons I learned from that dreadful introduction to deep sea fishing long ago.

- Be flexible with your schedule to maximize good weather and sea conditions. If you are susceptible to motion sickness in a car or plane this is an important indicator. Sticking to an exact time and date could set you up for a horrible experience. Charter companies want your repeat business and to enjoy the experience over and over again.

- Get plenty of rest before your fishing adventure. Come visit and if necessary spend the night. Start your day close to where you will be boarding the boat.

- Eat the right foods. You don’t need much food to start the day, keep it light and avoid fatty or sugary diet items. As the day goes by, eat snacks and lunch if you get hungry.

- Stay hydrated and in balance. Take in small sips when you are queasy or have thrown up. You need to drink but consuming several bottles of water in a short time period can create nausea.

- Avoid the smell zone. When possible, position yourself on the vessel to avoid intense odors like boat exhaust or fish waste in order to keep your stomach settled. It is best to stay away from other seasick individuals as their actions can influence your nausea.

- Mind over matter – Have confidence. Knowing you have prepared yourself to be on the water with sleep, diet, and hydration is often enough to avoid seasickness. However, if you routinely face motion or seasickness then a visit with your doctor can provide the best options to make your days at sea a blessing. Their help could be the final ingredient in your personal recipe for great times on the water with friends and family.

For more information, contact Scott Jackson at the UF/IFAS Extension Bay County Office at 850-784-6105.

by Rick O'Connor | Aug 3, 2018

In recent weeks, the country has heard about shark attacks off the Carolina coast and great whites off the northern coast of the Gulf of Mexico – then of course, we just completed “Shark Week”. This sometimes makes visitors to our beaches a bit unnerved about swimming. Each year we hear about how other activities we engage in are much more dangerous than swimming in the Gulf where there are sharks – and this is true – but we may still have a concern in the back of our minds. So – we will give you some information that will hopefully enlighten you on the issue of sharks.

First, what kind of sharks are in the Gulf and how common are they?

According to Dr. Hoese and Dr. Moore from Texas A&M, there are 30 species of sharks who have been found in the Gulf of Mexico – and this includes the great white. They range in size from the Cuban Dogfish (3 ft.) to the whale shark (60 ft. in length). Each has their own niche. Some, like the large whale sharks, are plankton feeders. Others, like the blue and mako, are open ocean travelers covering large stretches of water hunting prey. Others, like the blacktip and spinner, are more common near shore – close to estuary outfalls where food is plentiful. And others still, like nurses sharks, are bottom dwellers feeding on slow fish and crustaceans.

The Bull Shark is considered one of the more dangerous sharks in the Gulf. This fish can enter freshwater but rarely swims far upstream. Photo: Florida Sea Grant

As far as how common they are – I was involved in shark tagging in the early 1980’s and we tagged several species. Blacktips and spinner sharks were very common. We also tagged a lot of bull and dusky sharks – though dusky sharks are declining. Tiger sharks were not as common at the time. It was believed this was due to an increase in shark rodeos in the 1970’s – which were popular during the “Jaws” films. However, those events stopped for several years and recent shark events have once again captured tigers. There are five species of hammerheads that were tagged – the scalloped and bonnethead were the most common. White sharks and makos are in the Gulf but were never tagged. It was believed they spent more time offshore (where we were not sampling). Both species have been seen closer to shore in recent years, but there are no reports of any problems from this. It is possible they have been doing this all along and were just undetected. Blacknose, finetooth, and silky sharks were also frequently tagged.

People are probably not surprised to hear that sharks frequent the bays. Many of the species mentioned above do so. The small (3 ft.) Atlantic sharpnose shark is one of the most common. Sawfish were once common in the estuaries but have declined significantly across the region to do over harvesting in the early 20th century. They are currently protected.

You have probably also read that bull sharks have been found in freshwater rivers – and this is the case. Some have been found several miles up river systems.

What type of prey do sharks prefer and how to do they select and hunt for them?

This, of course, varies from species to species. Plankton feeding whale sharks generally cruise slowly through the water column filtering small fish and crustaceans – the same as the great whales. They do tend to feeding in deeper water during the day and closer to the surface at night. They are following what is known as the Deep Scattering Layer. This is a large layer of zooplankton (animal plankton) that migrates each day – deeper (600 feet or so) during the daylight hours and closer to the surface in the evenings.

Bottom dwelling sharks feed on benthic creatures like flounder and crabs. Many have the ability to detect their prey buried beneath the sand using electric perception they have.

Many species of sharks are what we call “ram-jetters”. This means they do not have a pump system to pump water over their gills. So, in order to breath, they must swim forward. Swimming continuously requires a lot of energy. Most of them are what we call opportunistic feeders – meaning they will grab what they can. Stomach analysis of such sharks find primarily fish and squid, but other creatures have been found – such as birds and even other sharks. The general rule here is seek prey that is “easy”. If your objective in feeding were to obtain energy – it would not make since to chase prey that would require a lot of energy to catch. Simple first, and take opportunities when you can. It is the ram-jetter species that people are most concerned. Swimming and taking opportunities. However, evidence suggest that we are not a prey of choice, not good opportunities. More on this in a minute.

Tiger sharks are interesting. It is in their stomachs we find such things as hubcaps, metal, and other sorts of garbage. Because of their tooth design, they are also capable of eating sea turtles.

How often do shark attacks on humans actually occur and what were the people doing that may have enticed it to happen?

Records on human shark attacks are kept at the International Shark Attack File at the Florida Museum of Natural History in Gainesville, FL. This data set only logs unprovoked attacks – those where the people were doing their thing and all of a sudden… Not those where humans were pulling them into their boats after fishing or grabbing their tails while diving.

Blacktip sharks are one of the smaller sharks in our area reaching a length of 59 inches. They are known to leap from the water. Photo: Florida Sea Grant

Based on this data – there have been 3031 unprovoked shark attacks reported worldwide since 1580 A.D. This equates to seven attacks / year. Granted… not all attacks are reported, particularly from the undeveloped regions of the world – and from early history, but it does give us something to look at.

Currently, we are averaging between 70 and 100 shark attacks worldwide and between 5-15 of these are fatal. Honestly, this is very low when compared to other activities in which humans participate.

| Year |

Deaths from Other |

Deaths from Shark Attacks |

| 1959 – 2010 |

Lightning strikes – 1970 |

26 |

| 2004 – 2013 |

Rip Currents – 361 |

8 |

| 2001 – 2013 |

Dog bites – 364 |

11 |

| 2000 – 2007 |

Hunting accidents – 441 |

7 |

| 2002 – 2013 (Florida only) |

Boating accidents – 782 |

2 |

As you can see… the risk is much lower.

It is true that most of the shark attacks worldwide are in the United States (46%) and that most in the U.S. are in Florida (56%). However, it is believed that this is due to the number of Americans (and Floridians) who enjoy water activities. In Florida, most of the encounters have been on the east coast – 89% of them! There have only been 65 attacks reported from the west coast – only 37 from the Florida panhandle – since 1580 A.D. There have only been six reported from Escambia County and one from Santa Rosa in that time.

As far as what people were doing when a shark attack occurred – most were surfing, but swimming has increased in recent years. This is believed to be connected to the increase in the number of humans swimming. The human population visiting beaches, particularly in the U.S., has increased significantly. Most shark attacks occur in near shore waters – which would make sense… that is where we are. Most are the “hit & run” version – meaning the shark hits the person and runs… not returning. Based on Florida reports, it is believed most of these are blacktips, spinners, and blacknose sharks. These rarely end in a fatality. “Bump & Bite” – meaning the shark circles, bumps the person, and then bites, are not as common. It is believed most of these are from great whites, tigers, and bull sharks. The few fatalities that happen are usually from this form of encounter.

Summary

When assessing “risk” in an activity you have to consider “control”. This means that the more you are in control of the situation, the less risky the activity seems to be. Most feel that in the water, the shark is in control – this increases our fear and risk concern. However, as mentioned in this article, many of the other activities we are involved – where we think we are in control – are far more risker than swimming on the open Gulf of Mexico.

However, shark attacks do occur and there are a few things swimmers can do to reduce their risk.

- Do not swim alone – all predators will try and isolate an individual from a group before they attack – much easier to attack an individual than a group

- Do not swim near dusk or after dark – to increase their chance of hunting success, sharks are more actively hunting in low light conditions

- Remove shiny objectives like jewelry – sunlight hitting metal objectives can appear to be baitfish to a shark

- Avoid blood in the water – it is true they have an excellent sense of smell – small amounts of blood in the water can be detected as far away as 100 feet suggesting easy prey nearby. Avoid swimming near fishing activity where bait and fish blood may be discharged into the water

I have been swimming in the Gulf all of my life. It is too much fun to worry about a low risk encounter with a shark. Follow the simple rules suggested by the ISAF and you should not have any problems.

Resources

The International Shark Attack File – https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/shark-attacks/.

Hoese, H.D., R.H. Moore. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana & Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M Press, College Station TX. pp. 327.

by Scott Jackson | Jul 14, 2017

The St Andrew Bay pass jetty is more like a close family friend than a collection of granite boulders. The rocks protect the inlet ensuring the vital connections of commerce and recreation. One of the treasured spots along the jetty is known locally as the “kiddie pool”, which is accessible from St Andrew’s State Park. There are similar snorkeling opportunities throughout northwest Florida. Jetties provide an opportunity to explore hard substrate or rocky marine ecosystems. These rocks are home to a variety of colorful sub-tropical and migrating tropical fish.

Snorkelers and divers who visit are likely to see a variety fish like sergeant majors, blennies, surgeon and doctor fish, just to name a few. Photo by L Scott Jackson.

Exploring a jetty is more like a sea-safari adventure than an experience in a real swimming pool – it is a natural place full of potential challenges that first time visitors need to prepare to encounter.

Divers and snorkelers are required to carry dive flags when venturing beyond designated swimming areas. These flags notify boaters that people are in the water. Brightly colored snorkel vests are not only good safety gear but they help you rest in the water without standing on rocks which are covered in barnacles and sometimes spiny sea urchins.

According to the Florida Department of Health, most sea urchin species are not toxic but some Florida species like the Long Spined Sea Urchin have sharp spines can cause puncture injuries and have venom that can cause some stinging. Swim and step carefully when snorkeling as they usually are attached to rocks, both on the bottom and along jetty ledges. Photo by L Scott Jackson

Dive booties also help protect your feet. I found out the hard way! A couple of years ago my foot hit against a sea urchin puncturing my heel. The open back of my dive fin did not provide any protection resulting in a trip to the urgent care doctor. My daughter later teased it was an “urchin care” doctor! Sea urchin spines are brittle and difficult to remove, even for a doctor. Lesson Learned: “Prevention is the best medicine”.

After a couple of weeks of limping around and a course of antibiotics, I recovered ready to return one of my favorite watery places – a little wiser and more prepared. I now bring a small first aid kit, just in-case, to help take care of small scrapes, cuts, and other minor injuries.

Gloves are recommended to protect hands from barnacle cuts and scrapes. Shirts like a surfing rash guard or those made from soft material help keep your body temperature warm on long snorkel excursions. Along with sunscreen, shirts also protect against sunburn.

There’s opportunity to see marine life from the time you enter the water with depths for beginning snorkelers at just a few feet deep. Some SCUBA divers also use the jetty for their initial training. Most underwater explorers are instantly hooked, and return for many years to come. Photo by L Scott Jackson

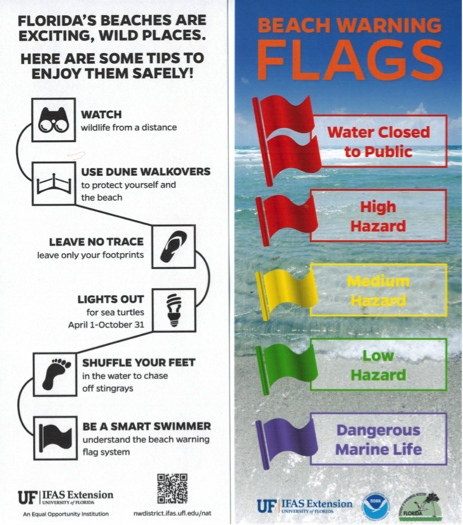

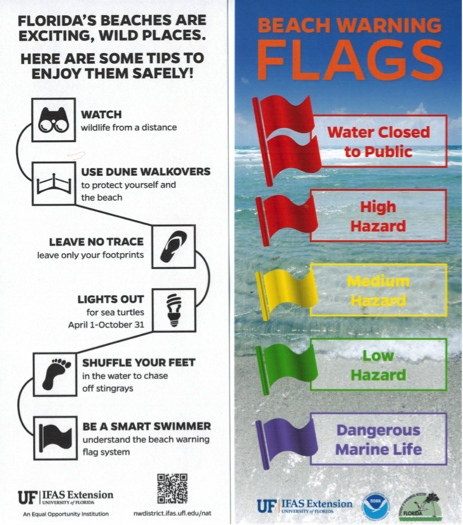

Finally, know the swimming abilities of yourself and your guests, especially when venturing to deeper areas. It’s good to have a dive buddy even when snorkeling. Pair up and watch out for each other. Be aware that currents and seas can change dramatically during the day. Know and obey the flag system. Double Red Flag means no entry into the water. Purple flags indicate presence of dangerous marine life like jellyfish, rays, and rarely even sharks. Local lifeguards and other beach authorities can provide specific details and up to date safety information.

Follow these beach safety tips for helping your family enjoy the beach while protecting coastal wildlife.

An Equal Opportunity Institution. UF/IFAS Extension, University of Florida, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, Nick T. Place, dean for UF/IFAS Extension. Single copies of UF/IFAS Extension publications (excluding 4-H and youth publications) are available free to Florida residents from county UF/IFAS Extension offices.

by Laura Tiu | Apr 14, 2017

It was disheartening to read that even with double red flags flying, 22 people had to be recused from the Gulf near Destin, FL recently, and one person lost their life. In that spirit, I believe it is important to review information on the importance of respecting our sometimes-unforgiving gulf.

First of all, stay calm.

Photo By: Laura Tiu

Swimmers getting caught in rip currents make up the majority of lifeguard rescues. These tips from Florida Sea Grant and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Weather Service (NWS) can help you know what to do if you encounter a rip current.

What Are Rip Currents?

Rip currents are formed when water flows away from the shore in a channeled current. They may form in a break in a sandbar near the shore, or where the current is diverted by a pier or jetty.

From the shore, you can look for these clues in the water:

- A channel of choppy water.

- A difference in water color.

- A line of foam, seaweed, or debris moving out to sea.

- A break in incoming wave patterns.

If you get caught in a rip current, don’t panic! Stay calm and do not fight the current. Escape the current by swimming across it–parallel to shore–until you are out of the current. When you get out of it, swim back to the shore at an angle away from the current. If you can’t break out of the current, float or tread water until the current weakens. Then swim back to shore at an angle away from the rip current. Rip currents are powerful enough to pull even experienced swimmers away from the shore. Do not try to swim straight back to the shore against the current.

Tips for Swimming Safely

You can swim safely this summer by keeping in mind some simple rules. Many people have harmed themselves trying to rescue rip current victims, so follow these steps to help someone stuck in a rip current. Get help from a lifeguard. If a lifeguard is not present, yell instructions to the swimmer from the shore and call 9-1-1. If you are a swimmer caught in a rip current and need help, draw attention to yourself–face the shore and call or wave for help.

Photo by: Laura Tiu

How Do I Escape a Rip Current?

- Rip currents pull people away from shore, not under the water. Rip currents are not “undertows” or “rip tides.”

- Do not overestimate your swimming abilities. Be cautious at all times.

- Never swim alone.

- Swim near a lifeguard for maximum safety.

- Obey all instructions and warnings from lifeguards and signs.

- If in doubt, don’t go out!

Adapted and excerpted from: “Rip Currents” Florida Sea Grant

The Foundation for the Gator Nation, An Equal Opportunity Institution.

by Laura Tiu | Jul 22, 2016

Dr. Monica Wilson, University of Florida Sea Grant, shares an update on the research that has occurred in the past five years since the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Presented in the Rodeo Room at the Destin History and Fishing Museum. Photo credit: Laura Tiu

The Deepwater Horizon (DWH) oil spill occurred about 50 miles offshore of Louisiana in April 2010. Approximately 172 million gallons of oil entered the Gulf of Mexico. Five years after the incident, locals and tourists still have questions. The Okaloosa County UF/IFAS Extension Office invited a Gulf of Mexico Oil Spill Scientist, Dr. Monica Wilson, to help answer the five most common questions about the oil spill and to increase the use of oil spill science by people whose livelihoods depend on a healthy Gulf.

The event was held at the Destin History and Fishing Museum on Monday evening, July 11, 2016. Executive Director, Kathy Marler Blue partnered with the University of Florida to host the event. “The Destin History and Fishing Museum has a vision that includes expanding its programs to include a lecture series,” said Blue. Over 20 interested individuals attended the lecture and the question and answer session was lively. This was the first in what hopes to be an ongoing lecture series, bringing more scientific information to our county.

Dr. Wilson is based in St. Petersburg, Florida with the Florida Sea Grant College Program. Monica uses her physical oceanography background to model circulation and flushing of coastal systems in the region and the impacts of tropical storms on these systems. She focuses on the distribution, dispersion and dilution of petroleum under the action of physical ocean processes and storms. For this lecture, she covered topics such as: the safety of eating Gulf seafood, impacts to wildlife, what cleanup techniques were used, how they were implemented, where the oil went, where is it now, and do dispersants make it unsafe to swim in the water?

The oil spill science outreach program also allows Sea Grant specialists to find out what types of information target audiences want and develop tailor-made products for those audiences. The outreach specialists produce a variety of materials, such as fact sheets and bulletins, focused on meeting stakeholder information needs. The specialists also gather input from target audiences through workshops and work with researchers to share oil spill research results at science seminars that are facilitated by the specialists.

The Destin History and Fishing Museum is a nonprofit organization whose members are dedicated to preserving, documenting, and sharing the complete history of Destin. Please subscribe to their Facebook page for information on upcoming events. The UF IFAS Extension Okaloosa County office also hosts a Facebook page with announcement of upcoming programs.

For additional information and publications related to the oil spill please visit: https://gulfseagrant.wordpress.com/oilspilloutreach/