by Laura Tiu | May 3, 2019

There are five species of sea turtles that nest from May through August on Florida beaches, with hatching stretching out until October. The loggerhead, the green turtle, and the leatherback all nest regularly in the Panhandle, with the loggerhead being the most frequent visitor. Two other species, the hawksbill and Kemp’s Ridley nest infrequently. All five species are listed as either threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act. Due to their threatened and endangered status, the Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission/Fish and Wildlife Research Institute monitors sea turtle nesting activity on an annual basis.

A group checks out a recently hatched sea turtle nest on the dunes in south Walton county in Florida.

Annual total nest counts for loggerhead sea turtles on Florida’s index beaches fluctuate widely and scientists do not yet understand fully what drives these changes. From 2011 to 2018, an average of 106,625 sea turtle nests (all species combined) were recorded annually on these monitored beaches. In 2018, there was a slight decrease in nests with only 96,945 nests recorded statewide. This is not a true reflection of all of the sea turtle nests each year in Florida, as it doesn’t cover every beach, but it gives a good indication of nesting trends and distribution of species.

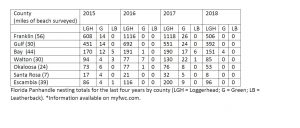

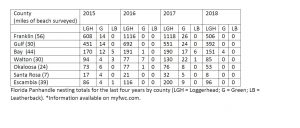

2015-2018 Florida Panhandle turtle nesting totals for all species.

If you want to see a sea turtle in the Florida Panhandle, please visit one of the state-permitted captive sea turtle facilities listed below, admission fees may be charged. Please call the number listed for more information.

- Gulf Specimen Marine Laboratory

222 Clark Dr

Panacea, FL 32346

850-984-5297

Admission Fee

- Gulf World Marine Park

15412 Front Beach Rd

Panama City, FL 32413

850-234-5271

Admission Fee

- Gulfarium Marine Adventure Park

1010 Miracle Strip Parkway SE

Fort Walton Beach, FL 32548

850-243-9046 or 800-247-8575

Admission Fee

- Navarre Beach Sea Turtle Center

8740 Gulf Blvd

Navarre, FL 32566

850-499-6774

The Foundation for The Gator Nation. An Equal Opportunity Institution

by Molly Jameson | Apr 18, 2019

With spring upon us, the mighty monarch butterflies have begun their long trek to the north from Mexico, looking to time their migration with growth of the milkweed plants in the southeastern United States. Mated monarch females lay hundreds of eggs along their journey, but only two percent of these eggs will survive to become mature caterpillars to carry on the next generation.

The monarch butterfly.

Photo: Steven Katovich USDA Forest Service

Monarch larvae rely exclusively on milkweed for nutrients, so it is of upmost importance that the plants are available to the offspring at the correct time. If the adult monarchs arrive too early, the milkweeds may not have had enough time to grow after late frosts. If they arrive too late, the milkweed vegetation may not support the nutrient needs of the caterpillars. In addition, the milkweeds contain a poisonous toxin, cardiac glycoside, that stays within the caterpillars’ bodies once consumed. This does not harm the larvae, but actually helps them, as it makes the young and adult butterflies taste terrible and makes them poisonous to potential predators.

For these reasons, it is important that we all do our part to support the growth of native milkweed species. Locally, the Monarch Milkweed Initiate at the St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge educates the public about milkweed and monarchs and grows and transplants native milkweed to support the monarchs on their migration.

When planting milkweed, be aware that there is a popular commercialized non-native tropical milkweed species that is not appropriate for the monarchs in our area. This species, Asclepias curassavica, can flower year-round, luring the monarchs to stay and breed in the winter when they should be on their way back to Mexico to escape freezing temperatures. Staying and breeding too long can make the monarchs susceptible to a protozoan parasite, Ophryocystis elektroscirrha (OE for short), that infects the caterpillars when feeding, reducing their lifespan, body mass, mating success rate, and ability to migrate.

Butterfly milkweed (Asclepias tuberosa)

Photo: John Ruter, University of Georgia

Swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata).

Photo: David Cappaert

Luckily, there are about 21 native milkweed species in Florida. Many native milkweeds in the Florida Panhandle require specialized care when grown for transplanting, as different species have adapted to a range of habitats. The Asclepias tuberosa, commonly referred to as butterflyweed, is considered easiest to grow as they transplant well and thrive in full sun. Others, such as Asclepias perennis, or aquatic milkweed, and Asclepias incarnata, swamp milkweed, must be grown using trays without drain holes, as their “feet” must be kept wet. The Asclepias humistrata, or sandhill milkweed, requires a drier, heavier soil.

Monarch catepillar (Danaus plexippus).

Photo: Steven Katovich, USDA Forest Service

To support the monarchs and grow milkweed in your garden, come to the Leon County Extension Office at 615 Paul Russell Road on Saturday, May 11, from 9:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. for the Spring Open House and Plant Sale. Master Gardeners have been busy growing native milkweeds for this event and will be on hand selling the transplants. There will also be many other Florida Friendly and native plants available, along with guided garden tours, kids’ activities, the UF/IFAS Bookstore, a silent auction, live music by the Tallahassee Woodwind Quintet, refreshments, and Master Gardeners and Extension Agents on-hand to answer any of your gardening questions.

by Ray Bodrey | Apr 17, 2019

Soon, two important ecological surveys will begin in Gulf County, concerning both diamondback terrapins and mangroves.

Florida is home to five subspecies of diamondback terrapin, three of which occur exclusively in Florida. Diamondback terrapins live in coastal marshes, tidal creeks, mangroves, and other brackish or estuarine habitats. However, the diamondback terrapin is currently listed as a Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN).

Diamondback terrapin populations, unfortunately, are nationally in decline. Human activities, such as pollution, land development and crabbing without by-catch reduction devices are often reasons for the decline, but decades ago they were almost hunted to extinction for their tasty meat. The recent decline has raised concern of not only federal agencies, but also organizations and community groups on the state and local levels. Diamondback Terrapin range is thought to have once been all of coastal Florida, including the Keys.

Figure 1: Diamondback Terrapin.

Credit: Rick O’Connor, UF/IFAS Extension & Florida Sea Grant, Escambia County.

Mangroves, a shoreline plant species of south Florida, are migrating north and are now being found in the Panhandle. Both red and black mangroves have been found in St. Joseph Bay. Mangroves establishment could be an important key to a healthy bay ecosystem, as a factor in shoreline restoration and critical aquatic life habitat.

Currently there is a significant data gap for both diamondback terrapin and mangrove populations. Therefore, there is a great need to conduct assessments to learn more about their geographic distribution.

Figure 2. Black Mangrove in St. Joseph Bay.

Credit: Ray Bodrey, UF/IFAS Extension & Florida Sea Grant, Gulf County.

The Forgotten Coast Sea Turtle Center is partnering with UF/IFAS Extension & Florida Sea Grant to assist in surveying and monitoring diamondback terrapins and mangroves in St. Joseph Bay, and we need your help! UF/IFAS Extension & Florida Sea Grant Agent’s Rick O’Connor and Ray Bodrey are providing a training workshop for volunteers and coordinating surveys for St. Joseph Bay. Terrapin surveys require visiting an estuarine location where terrapin nesting sites and mangrove plants are highly probable. Volunteers will visit their assigned locations at least once a week during the months of May and June and complete data sheets for each trip. Each survey takes about two hours, and some locations may require a kayak to reach.

If you are interested in volunteering for these important projects, we will hold a training session on Monday, April 22nd at 1:00 p.m. ET at the Forgotten Coast Sea Turtle Center (located at 1001 10th Street, Port St. Joe).

For more information, please contact:

Ray Bodrey, UF/IFAS Extension Gulf County, Extension Director

rbodrey@ufl.edu

(850) 639-3200

UF/IFAS Extension is an Equal Opportunity Institution.

by Rick O'Connor | Mar 29, 2019

We have a lot of really cool and interesting creatures that live in our bay, but one many may not know about is a small turtle known as a diamondback terrapin. Terrapins are usually associated with the Chesapeake Bay area, but actually they are found along the entire eastern and Gulf coast of the United States. It is the only resident turtle of brackish-estuarine environments, and they are really cool looking.

The diamond in the marsh. The diamondback terrapin.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

Terrapins are usually between five and 10 inches in length (this is the shell measurement) and have a grayish-white colored skin, as opposed to the dark green-black found on most small riverine turtles in Florida. The scutes (scales) of the shell are slightly raised and ridged to look like diamonds (hence their name). They are not migratory like sea turtles, but rather spend their entire lives in the marshes near where they were born. They meander around the shorelines and creeks of these habitats, sometimes venturing out into the seagrass beds, searching for shellfish – their favorite prey. Females do come up on beaches to lay their eggs but unlike sea turtles, they prefer to do this during daylight hours and usually close to high tide.

Most folks living here along the Gulf coast have not heard of this turtle, let alone seen one. They are very cryptic and difficult to find. Unlike sea turtles, we usually do not give them a second thought. However, they are one of the top predators in the marsh ecosystem and control plant grazing snails and small crabs. During the 19th century they were prized for their meat in the Chesapeake area. As commonly happens, we over harvested the animal and their numbers declined. As numbers declined the price went up and the popularity of the dish went down. There was an attempt to raise the turtles on farms here in the south for markets up north. One such farm was found at the lower end of Mobile Bay.

Early 20th century still found terrapin on some menus, but the popularity began to wane, and the farms slowly closed. Afterwards, the population terrapins began to rebound – that was until the development of the wire meshed crab trap. Developed for the commercial and recreational blue crab fishery, terrapins made a habitat of swimming into these traps, where they would drown. In the Chesapeake Bay area, the problem was so bad that excluder devices were developed and required on all crab traps. They are not required here in Florida, where the issue is not as bad, but we do have these excluders at the extension office if any crabber has been plagued with capturing terrapins. Studies conducted in New Jersey and Florida found these excluder devices were effective at keeping terrapins out of crab traps but did not affect the crab catch itself. Crabs can turn sideways and still enter the traps.

This orange plastic rectangle is a Bycatch Reduction Device (BRD) used to keep terrapins out of crab traps – but not crabs.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Another 20th century issue has been nesting predation by raccoons. As we began to build roads and bridges to isolated marsh islands in our bays, we unknowingly provided a highway for these predators to reach the islands as well. On some islands, raccoons depredated 90% of the terrapin nests. Today, these turtles are protected in every state they inhabit except Florida. Though there is currently no protection for the terrapin itself in our state, they do fall under the general protection for all riverine turtles; you may only possess two at any time and may not possess their eggs.

Some scientists have discussed identifying terrapins as a sentinel species for the health of estuaries. Not having terrapin in the bay does not necessarily mean the bay is unhealthy, but the decline of this turtle (or the blue crab) could increase the population of smaller plant grazing invertebrates they eat throwing off the balance within the system.

Sea Grant trains local volunteers to survey for these creatures within our bay area. Trainings usually take place in April and surveys are conducted during May and June. This year we will be training volunteers in the Perdido area on April 10 at the Southwest Branch of the Pensacola Library on Gulf Beach Highway. That training will begin at 10:00 AM. For Pensacola Beach the training will be on April 15 at the Navarre Beach Sea Turtle Conservation Center on Navarre Beach. That training will begin at 9:00 AM. A third training will take place on April 22 at the Port St. Joe Sea Turtle Center in Port St. Joe. For more information on diamondback terrapins contact me at the Escambia County Extension Office – (850) 475-5230 ext. 111.

by Rick O'Connor | Feb 10, 2019

On a recent trip to Santa Rosa Island, my wife saw two bald eagles flying down the shore of Santa Rosa Sound. Wanting photos of the nest, we searched and found two individuals in a small nest (for an eagle) in a tall pine. One individual was an adult, the other a juvenile.

Bald eagle nest on Santa Rosa Island.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

Seeing bald eagles is like seeing bottlenose dolphins. I do not care how many times you have seen them over the course of your life, it is always exciting. Growing up here, I do not remember these animals in our area. Of course, their numbers suffered greatly during the DDT period, and poaching was (and still can be) a problem. But both the banning of DDT and the listing on the Endangered Species List did wonders for this majestic bird. They now estimate over 250,000 breeding populations in North America and 88% of those within the United States. Florida has some of the highest densities of nests in the lower 48 states. Though the bird is no longer listed as an endangered species, it is still protected by the Florida Eagle Rule, the federal Migratory Bird Treaty, and the federal Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act.

It was shortly after Hurricane Ivan that someone told me they had seen a bald eagle in the area. My first reaction was “yea… right… bald eagle”. Then one afternoon on my back porch, my wife and I glanced up to see two flying over. Now we see them every year. The 2016 state report had 12 nesting pairs in the Pensacola Bay area. They were in the Perdido Bay area, Escambia Bay area, Holly-Navarre area, and Pensacola Beach area. Many locals now see these birds flying over our coastlines searching for food and nesting materials on a regular basis.

An adult and juvenile bald eagle on nest in Montana.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

Bald eagles are raptors with a thing for fish. However, they are opportunistic hunters feeding on amphibians, reptiles, crabs, small mammals, and other birds. They are also notorious “raiders” stealing fish from osprey, other raptors, and even mammals. They are also known scavengers feeding on carrion and visiting dumps looking for scraps. Benjamin Franklin was in favor of the turkey for our national emblem because the bald eagle was of such low moral character – referring their stealing and scavenging habit.

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology list the bald eagle as a year-round resident along the Gulf coast, but most of us see them in the cooler months. Their nesting period is from October through May. They select tall trees near water and build their nest just below the crown of the canopy. One local ecotourism operator has noticed their preference for live trees over the dead ones selected by osprey. Eagle nest are huge. A typical one will be 5-6 feet in diameter and 2-4 feet tall. The record was a nest found in St. Pete FL that was 10 feet in diameter and over 20 feet tall! The inside of the nest is lined with lichen, small sticks, and down feathers. One to three eggs are typically laid each season, and these take about 35 days to hatch. Both parents participate in nest building and raising of the young.

Viewing bald eagles is amazing, but approaching nests with eggs, or hatchlings, can be stressful for the parents. Hikers and motorized vehicles should stay 330 feet from the nests when viewing. Bring a distance lens for photos and be mindful of your presence.

An adult and juvenile bald eagle are perched in a dead tree near their nest.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

No matter how times you see these birds, it is still amazing. Enjoy them.

References

Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. Bald Eagle Management. 2018. https://myfwc.com/wildlifehabitats/wildlife/bald-eagle/.

Jimbo Meador, personal communication. 2017.

Williams, K. 2017. All About Birds, the Bald Eagle. Cornell University Lab of Ornithology. https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Bald_Eagle/overview.

by Rick O'Connor | Jan 31, 2019

As we begin our wildlife series for 2019, we will start with a snake that almost everyone has encountered but knows little about – the southern black racer.

The southern black racer differs from other black snakes in its brilliant white chin and thin sleek body.

Photo: Jacqui Berger.

This snake is common for many reasons.

- It is found throughout the eastern United States

- It is diurnal, meaning active during daylight hours when we are out and about

- It can be found in a variety of habitats and is particularly fond of “edge” areas between forest and open habitat – they do very well around humans.

The southern black racer (Coluber constrictor priapus) is one of eight subspecies of this snake found in the United States. This local variety is a beautiful shiny black. The shine is due to the fact that they have smooth, rather than keeled, scales. It is a long snake, reaching up to six feet, but very thin – and very fast! Most of us see it just before it darts away.

They are sometimes confused with the cottonmouth. It can be distinguished in having a long “thin” body, as compared to the cottonmouths shorter “thick” body. It has a brilliant white chin and the top of the head is solid black. Cottonmouths can be mottled, usually have a cream-colored chin with a dark “mask” extending from the lower point of the chin through the eye. Cottonmouths also have the wide delta shaped head compared the finger-shaped head of the racer. They are also confused with the eastern indigo snake. The indigo is very long (up to eight feet) large bodied snake, and the lower chin is a reddish-orange color. The coachwhip is a close cousin of the racer, found in many of the same habitats. It has a similar body shape, and speed, but is a light tan color with a dark brown-black head and neck.

The juvenile black racer looks more like a corn snake, and is sometimes confused with a pygmy rattler.

Photo: C. Kelly

The juvenile looks nothing like the adult. The young racers hatch from rough covered eggs laid in late winter and early spring. They typically lay between 6-20 eggs and hide them under rocks, boards, bark, and even in openings in the side of homes. In late spring and early summer, they hatch. Their body resembles adults, but their coloration is a mottled mix of grays, browns, and reds – having distinct patches on their backs. This helps with camouflage but often they are mistaken for pygmy rattlesnakes and are killed.

They are great climbers and are found in our shrubs and trees, as well as on our houses and in our garages. Though sometimes confused with the cottonmouth, this snake is non-venomous and harmless. Harmless in the sense that a bite from will cause no harm – but it will bite. Black racers are notorious for this. If approached, it generally freezes first – to avoid detection. If it believes it has been detected, it will flee at amazing speeds. If it cannot flee, it will turn and bite… repeatedly. Again, the bites are harmless, but could draw blood. Cleaning with soap and water is all you need.

They are opportunistic feeders hunting a variety of prey including small mammals, reptiles, birds, insects, and eggs. They also hunt snakes, including small venomous species. Unlike the larger venomous snakes, black racers stalk their prey – many times with their heads raised similar to cobras. When prey is detected, they spring on them with lighting speed. Despite the scientific name “constrictor”, they do not constrict their prey, rather pin it down and wait for it to suffocate.

They do have their predators, particularly hawks. When approached they will first freeze to avoid detection, they may release a foul-smelling musk as a warning, and sometimes will vibrate their tails. In leaf-litter, this can sound very similar to a rattlesnake – not helping with the juvenile identification confusion. One paper reported finding a dead great horned owl with a black racer in its talons. Apparently, the owl grabbed the snake too far back. It killed the snake but not before the snake was able to strangle the owl.

They are hibernating this time of year but will soon be laying another clutch of eggs and we will once again encounter this most common of snakes.

References

Florida Museum of Natural History. Southern Black Racer (Coluber constrictor priapus). http://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/herpetology/fl-snakes/list/coluber-constrictor-priapus/.

Gibbons, W., M/ Dorcas. 2005. Snakes of the Southeast. University of Georgia Press, Athens GA. pp. 253.

Perry, R.W., R.E. Brown, D.C. Rudolph. 2001. Mutual Mortality of a Great Horned Owl and a Southern Black Racer: a Potential Risk for Raptors Preying on Snakes. The Willson Bulletin, 113(3). http://doi.org/10.1676/0043-5643(2001)113[0345:MMOGH0]2.0.CO;2.

Willson, J.D. Species Profile: Black Racer (Coluber constrictor priapus). SREL Herpetology. www.srelherp.uga.edu/snakes/colcon.htm.