by Sheila Dunning | Oct 16, 2020

That’s the question from a recent group exploring what washed up on the beach after Hurricane Sally.

Sea Cucumber

Photo by: Amy Leath

They have no eyes, nose or antenna. Yet, they move with tiny little legs and have openings on each end. Though scientists refer to them as sea cucumbers, they are obviously animals. Sea cucumbers get their name because of their overall body shape, but they are not vegetables.

There are over 1,200 species of sea cucumbers, ranging in size from ¾“ to more than 6‘ long, living throughout the world’s ocean bottoms. They are part of a larger animal group called echinoderms, which includes starfish, urchins and sand dollars. Echinoderms have five identical parts to their bodies. In the case of sea cucumber, they have 5 elongated body segments separated by tiny bones running from the tube feet at the mouth to the opening of the anus. These squishy invertebrates spend their entire life scavenging off the seafloor. Those tiny legs are actually tube feet that surround their mouth, directing algae, aquatic invertebrates, and waste particles found in the sand into their digestive tract. What goes in, must come out. That’s where it becomes interesting.

Sea cucumbers breathe by dilating their anal sphincter to allow water into the rectum, where specialized organs referred to as respiratory trees (or butt lungs) extract the oxygen from the water before discharging it back into the sea. Several commensal and symbiotic creatures (including a fish that lives in the anus, as well as crabs and shrimp on its skin) hang out on this end of the sea cucumber collecting any “leftovers”.

But, the ecosystem also benefits. Not only is excess organic matter being removed from the seafloor, but the water environment is being enriched. Sea cucumbers’ natural digestion process gives their feces a relatively high pH from the excretion of ammonia, protecting the water surrounding the sea cucumber habitats from ocean acidification and providing fertilizer that promotes coral growth. Also, the tiny bones within the sea cucumber form from the excretion of calcium carbonate, which is the primary ingredient in coral formation. The living and dying of sea cucumbers aids in the survival of coral beds.

When disturbed, sea cucumbers can expose their bony hook-like structures through their skin, making them more pickle than cucumber in appearance. Sea cucumbers can also use their digestive system to ward of predators. To confuse or harm predators, the sea cucumber propels its toxic internal organs from its body in the direction of the attacker. No worries though. They can grow them back again.

Hurricane Sally washed the sea cucumbers ashore so you could learn more about the creatures on the ocean floor. Continue to explore the Florida panhandle outdoor.

by Rick O'Connor | Oct 2, 2020

Is this what it sounds like? Fish that do not swim, but drift? Well… yes and no. They can swim, just not very well – they do better by drifting.

The word used most often for any drifting creature in the sea is plankton. Plankton literally means “drifter” or “wanderer”. Most plankton, including planktonic fish, can swim. Some can adjust their position in the water column – rising near the surface at night, sinking deeper during the day.

When you think about it, it is a cool way to make a living out there. With miles and miles of open blue water, the swimming fish must keep swimming. To do this requires a lot of energy, open water fish must consume a lot of high energy food. Drifters just drift. Hang with the currents, enjoying the moment, eating what they can. Sounds pretty good huh?

As you can imagine, there are not many fish who live this lifestyle. Many do after they hatch in their larval stage – but as adults, most live on the bottom, others in the open blue. Let’s meet a couple of the drifters.

The slow moving ocean sunfish.

Photo: NOAA

Sunfish

Now here is one weird looking fish. Large bulbous head, long angular dorsal and ventral fins, and no tail – it’s a swimming/drifting head. These large open water drifters can reach seven feet long, seven feet high, and weigh over a ton. They can hold their position, undulating their dorsal and ventral fins, and move slowly through the water. Often, they will turn on their sides and just hang there. Looking like a floating board or something, small creatures are attracted to them, some of which they eat. Their diet is primarily jellyfish, though they have been known to take small fish, crustaceans, and even algae.

They are related to puffer fish, and actually resemble them early in life, but the resemblance fades quickly as this becomes more head than anything else.

Though rarely seen near shore, they have been, and one was actually spotted inside Pensacola Bay. They occasionally wash ashore dead. One did on Dauphin Island. The staff at the Sea Lab made a mold of the dead creature which is now hanging in the public Estuarium there. Many know this fish by its scientific name – Mola mola – or simply “the mola”. It is a pretty cool fish.

https://www.montereybayaquarium.org/animals/animals-a-to-z/ocean-sunfish/

This sargassum fish is well camouflaged within this mat of sargassum weed.

Photo: Florida Museum of Natural History

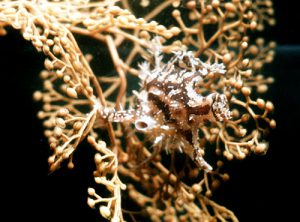

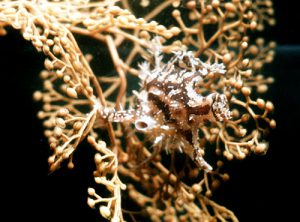

Sargassum Fish

Sargassum fish are members of a family known as “frogfish” – so you can guess what they must look like – and can guess they are not real good swimmers. Almost completely round, they are blobs in the sea. There are three species in the Gulf, two if which are bottom fish. However, the Sargassum fish is a drifter – drifting with the common seaweed known by its scientific name Sargassum. Sargassum is brown algae that produces air bladders called pneumatocyst. These bladders allow the weed to drift in large mats at the surface where they get sunlight. Some sargassum mats are huge is size and are an ecosystem amongst themselves. Hundreds of miniature fish and invertebrates call this place home – a place to hide in the open sea. It is the home of baby sea turtles, if they can make the trek from the beach alive.

One member of this community is the Sargassum fish (Histrio histrio). It has the typical frogfish shape and look but the coloration matches the Sargassum weed perfectly. Like other frogfish, the first dorsal spine is modified into a “fishing rod” complete with a “lure”. When prey (small creatures in the Sargassum weed) are in view, the Sargassum fish will extend the illicium (as it is called) and actually move it back and forth to make it look like live bait – they are fishing.

Most members of the Sargassum community flee the weed when the currents bring it to close to the beach. However, they hang on longer than you might think. If you are at the beach when the Sargassum is drifting just off the shore – wade out with a small kids dip net and snag a patch. Place in a bucket and see who comes out. You MIGHT get lucky and catch one of these ocean drifters.

by Ray Bodrey | Sep 20, 2020

Ray Bodrey is in his fifth year as the Gulf County Extension Director. Ray is originally from the “Watermelon Capital of the World” – Cordele, GA, where he grew up on a family row crop farm. His extension areas are Agriculture, Natural Resources (including Sea Grant programs) and Horticulture. He holds degrees in Biology, (B.S. 2006, Georgia Southern University); Agricultural Leadership, (M., 2011, University of Georgia) and Soil & Water Sciences, (M.S. 2015, University of Florida). Ray is also beginning his second year of the PhD program in UF’s Soil & Water Sciences Department. His research concerns strategies for building soil health after timber to pasture land conversion.

Ray’s natural resources programming efforts include teaching courses for the Florida Master Naturalist Program and Panhandle Outdoor Live Water Schools. Ray has also trained and managed volunteers for citizen science programs. These programs include mangrove and diamondback terrapin tracking and monitoring, scallop restoration (scallop sitters) and coastal water quality assessments, through which, the St. Joseph Bay Water Watch Program was established. He is also involved with wildlife food plot on-farm trials and was a team member of the sea turtle-friendly lighting initiative.

Before coming to UF/IFAS Extension, Ray was a member of the Water Quality Program of the University of Georgia Marine Extension Service – Georgia Sea Grant Program for eight years. As a Marine Resource Specialist, Ray’s extension and research centered on nonpoint source pollution activity in coastal surface waters.

When not juggling extension hats, Ray enjoys fishing, hunting, gardening and really, just being in the great outdoors. Growing skyscraper sunflowers, raised bed gardening, home composting and caring for citrus and peach trees are just some of the fun times had around his homestead.

by Sheila Dunning | Jul 16, 2020

Credits: Clemson University, www.insectimages.org

The hickory horned devil is a blue-green colored caterpillar, about the size of a large hot dog, covered in long black thorns. They are often seen feeding on the leaves of deciduous forest trees, such as hickory, pecan, sweetgum, sumac and persimmon. For about 35 days, the hickory horned devil continuously eats, getting bigger and bigger every day. In late July to mid-August, they crawl down to the ground to search for a suitable location to burrow into the soil for pupation. While the hickory horned devil is fierce-looking, they are completely harmless. If you see one wandering through the grass or across the pavement, help it out by moving it to an open soil surface.

The pupa will overwinter until next May to early-June, at which time, they completely metamorphosize into a regal moth (Citheronia regalis). Like most other moths, it is nocturnal. But, this is a very large gray-green moth with orange wings, measuring up to 6 inches in width. It lives only about one week and never get to eat. In fact, they don’t even have a functional mouth. Adults mate during the second evening after emergence from the ground and begin laying eggs on tree leaves at dusk of the third evening. The adult moth dies of exhaustion. Eggs hatch in six to 10 days.

Adult regal moth, Citheronia regalis (Fabricius).Credits: Donald W. Hall, UF/IFAS

The regal moth, and its larvae stage called the hickory horned devil, is native to the southeastern United States. The damage they do to trees in minimal. Learning to appreciate this “odd” creature is something we can all do. For more information: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/IN/IN20900.pdf

by Laura Tiu | May 22, 2020

Have you ever been on a walk, passed a beautiful flowering bush, and wondered what it was? Well, wonder no more! You can become an expert naturalist by using an easy smartphone app, iNaturalist. With one easy download, you can connect with others to identify species and document their occurrence.

iNaturalist is a community of naturalists, citizen scientists and biologists working together to share observations of biodiversity and map the occurrence. Parents need to know that iNaturalist is an online community that allows users age 13 and older to share pictures and locations of the living things they see around them. While considered very safe, like any online network, teens should be cautious with sharing.

Getting started is easy. All you need to do is create an account at iNaturalist.org and download their free iNaturalist app to your smartphone (Android or iOS). You can then start making your own nature observations, upload them to iNaturalist where you can share your discoveries with others, and also let other iNaturalist users help identify what you have seen.

iNaturalist is a great way to connect with nature and generate scientifically valuable biodiversity data. You can use it for your own personal fulfillment, or as part of a group. You can even use the project feature which allows you to have a central page that displays all the observations made within a location, or all observations made by a group. Why not organize your neighbors, club, or friends and challenge them to post their observations?

Mystery blob in the garden. Can you figure out what it is? Photo: Laura Tiu

I recently used iNaturalist to identify a bright yellow blob that sprung up in my garden overnight. I won’t spoil the surprise by telling you what it is. Why don’t you head on over to iNaturalist.org and see if you can figure it out? It will be your first step to becoming an expert naturalist.

by Rick O'Connor | Apr 30, 2020

Okay, this is a gamble.

I began this series to celebrate the year of the Gulf of Mexico – “Embracing the Gulf 2020”. The idea was to write about the habitats, creatures, economic impacts, and issues surrounding the “pond” that we live on. I did a few introductory articles and then jumped right into the animals. We began with the fun ones – fish, sea turtles, whales – and now we are in the more unfamiliar – invertebrates like sponges and jellyfish.

But worms? Really? Who wants to read about worms?

A classic flatworm is this lung fluke.

Photo: Kansas State University.

Well, there are a lot of them, and they are everywhere. You will find in many sediment samples that worms dominate. They also play an important role in the marine community. They are great scavengers, cleaning the environment, and an important source of food in the food chains of the more familiar animals. But they are gross and creepy. When we find worms, we think the environment is gross and creepy – and sometimes it is, remember they CLEAN THE ENVIRONMENT. But worse is that many are parasites. Yes… many of them are, and that is certainly gross and creepy. Flukes, tapeworms, hookworms, leeches, who wants to learn amore about those? Well, honestly, parasitism is an interesting way to find food and the story on how they do this is pretty interesting… and gross… and creepy. Let’s get started.

According to Robert Barnes’ 1980 book Invertebrate Zoology, there are at least 11 phyla of worms – it is a big group. We are not going to go over all of them, rather I will focus on what I call the “big three”: flatworms, roundworms, and segmented worms. We will begin with the most primitive, the flatworms.

As the name implies, these worms are flat. They are so because they are the last of what we call the “acoelomate” animals. Acoelomates are animals that lack an internal body cavity and, thus, have no true body organs – there is no where for them to go. So, they absorb what they need, and excrete, through special cells in their skin. To be efficient at this, they are flat – this increases the surface area in contact with the environment. There are three classes of flatworms – one free swimming, and two that are parasitic.

This colorful worm is a marine turbellarian.

Photo: University of Alberta

The free-swimming ones are called turbellarians. Most are very small, look like leaves, very colorful, and undulate as they swim near the bottom. They have “eye-like” cells called photophores that allow them to see light – they can then choose whether to move towards the dark or not. They have nerve cells but no true brain, and one only one opening to the digestive tract – that being the mouth, so they must eat and go to the bathroom through the same opening. Weirder yet, the mouth is usually in the middle of the body, not at the head end. Some are carnivorous feeding on small invertebrates, others prefer algae, others are scavengers (CLEANING THE OCEAN). They can reproduce by regenerating their bodies but most use sexually reproduction. They are hermaphrodites – being both male and female. They can fertilize themselves but more often seek out another worm. Fertilization is internal and they lay very few eggs.

The human liver fluke. One of the trematode flatworms that are parasitic.

Photo: University of Pennsylvania

The second group are called trematodes and they are the parasites we know as “flukes”. We have heard of liver flukes in livestock and humans, but there are marine versions as well. They have adhesive organs located at the near the mouth that help hold on, and a type of skin that protects them from their hosts’ defensive enzymes. They feed on cells, mucous, and sometimes blood – yep… gross and creepy. Some are attached outside of their hosts body (ectoparasites) others are attached to internal organs (endoparasites). The ectoparasites breath using oxygen (aerobic), endoparasites are anaerobic. Like their turbellarian cousins, they are hermaphroditic and use internal fertilization to produce eggs. They differ though in that they produce 10,000 – 100,000 eggs! Their primary host (the one they spend their adult life feeding on) is always a vertebrate, fish being the most common. However, their life cycle requires the hatching larva find an intermediate host where they go through their developmental growth before returning to a primary host. These intermediate host are usually invertebrates, like snails. The eggs are released with the fish feces – a swimming larva is released – enters a snail – begins part of the developmental growth – consumed by an arthropod (like a crab) – completes development – and the crab is consumed by the fish – wah-la. The adults are usually found in the gills/lungs, liver, or blood of the vertebrate hosts. Gross and creepy.

The famous tapeworm.

Photo: University of Omaha.

Better yet are the tapeworms. We have all heard of these. They are also all parasites, but all are endoparasites. Weirder, they do not have a digestive tract. Gross and creepy. Their heads are very tiny compared to their bodies and have either four sets of suckers, or hooks, to hold onto the digestive tract of their hosts (usually vertebrates). The head is actually round but the body is very flat and divided into squares called proglottids. Each proglottid gets larger as you move towards the tail and each possesses all of the reproductive material needed to produce new worms – they too are hermaphrodites. They also have a type of skin that protects them from the enzymes of their hosts. They also require an intermediate host to complete their life cycle so the proglottids will exit the hosts body via feces and complete the cycle similar to the trematodes.

I began this with a comment on how worms benefit the overall marine environment of the Gulf. It is hard to see that in these flatworms. They are either just another consumer out there, or nasty parasites others in the community must deal with. Well… we look at the roundworms next time and see what they have to offer.

Reference

Barnes, R. 1980. Invertebrate Zoology. Saunders College Press. Philadelphia, PA. pp. 1089.