by Rick O'Connor | Jan 31, 2019

“The Gulf of Mexico provides food, shelter, protection, security, energy, habitat, recreation, transportation, and navigation – playing an important role in our communities, states, region, and nation. To highlight the value and the vitality of the Gulf of Mexico region, the Gulf of Mexico Alliance conceived an awareness campaign “Embrace the Gulf” for the entire year 2020. The awareness campaign will culminate in a multi-stakeholder, cross-sector celebration of the importance of the Gulf of Mexico throughout the year 2020.” (https://embracethegulf.org/about/)

Join the Gulf of Mexico Alliance as we celebrate the importance of the Gulf of Mexico during the year 2020. The Gulf of Mexico Alliance is a regional partnership that works to “sustain the resources of the Gulf of Mexico. Led by the five Gulf States, the broad partner network includes federal agencies, academic organizations, businesses, and other non-profits in the region. Our goal is to significantly increase regional collaboration to enhance the environmental and economic health of the Gulf of Mexico.” (https://gulfofmexicoalliance.org/about-us/organization/).

The Gulf of Mexico Alliance (GOMA) was established in 2004 by the Governors of the Gulf states, as a response to the President’s Ocean Action Plan. It began as a network of state partnerships that worked together on various strategies related to the GOMA priority issues identified by the Governors of each state. It had strong support from the U.S. Council on Environmental Quality. Today GOMA is led by the EPA and NOAA, with 13 federal agencies support the effort. Learn more.

A great blue heron enjoying the Gulf of Mexico.

Photo: Chris Verlinde

To celebrate the year 2020 and the importance of Gulf of Mexico, the Embrace the Gulf campaign was created by the Education and Engagement Priority team. The GOMA leadership supports the idea and the campaign has gathered support from the other priority areas.

There are many ways for you and or your organization to get involved. You can plan an event to celebrate the Gulf of Mexico. You can utilize GOMA marketing resources to promote the campaign. Click here to learn about the available marketing resources.

The E& E team is collecting 365 facts to promote the Gulf of Mexico. You can support this effort by submitting Gulf of Mexico facts using the online form that is located here. Facts will be used on social media, the GOMA website and more. Please support this effort by submitting today!!

Check out this You Tube video GOMA produced to promote the beauty and importance of the Gulf of Mexico. Join us as we celebrate 2020 to Embrace the Gulf!!

by Sheila Dunning | Jan 4, 2019

Tree planting in Mary Esther

The best time to plant a tree is twenty years ago. The second best time is for Arbor Day. Florida recognizes the event on the third Friday in January, but planting any time before spring will establish a tree quickly. Arbor Day is an annual observance that celebrates the role of trees in our lives and promotes tree planting and care. As a formal holiday, it was first observed on April 10, 1872 in the state of Nebraska. Today, every state and many countries join in the recognition of trees impact on people and the environment. Trees are the longest living organisms on the planet and one of the earth’s greatest natural resources. They keep our air supply clean, reduce noise pollution, improve water quality, help prevent erosion, provide food and building materials, create shade, and help make our landscapes look beautiful. A single tree produces approximately 260 pounds of oxygen per year. That means two mature trees can supply enough oxygen annually to support a family of four. The idea for Arbor Day in the U.S. began with Julius Sterling Morton. In 1854 he moved from Detroit to the area that is now the state of Nebraska. J. Sterling Morton was a journalist and nature lover who noticed that there were virtually no trees in Nebraska. He wrote and spoke about environmental stewardship and encouraged everyone to plant trees. Morton emphasized that trees were needed to act as windbreaks, to stabilize the soil, to provide shade, as well as, fuel and building materials for the early pioneers to prosper in the developing state. In 1872, The State Board of Agriculture accepted a resolution by J. Sterling Morton “to set aside one day to plant trees, both forest and fruit.” On April 10, 1872 one million trees were planted in Nebraska in honor of the first Arbor Day. Shortly after the 1872 observance, several other states passed legislation to observe Arbor Day. By 1920, 45 states and territories celebrated Arbor Day. Richard Nixon proclaimed the last Friday in April as National Arbor Day during his presidency in 1970. Today, all 50 states in the U.S. have official Arbor Day, usually at a time of year that has the correct climatological conditions for planting trees. For Florida, the ideal tree planting time is January, so Florida’s Arbor Day is celebrated on the third Friday of the month. Similar events are observed throughout the world. In Israel it is the Tu B Shevat (New Year for Trees). Germany has Tag des Baumes. Japan and Korea celebrate an entire week in April. Even, Iceland one of the most treeless countries in the world observes Student’s Afforestation Day. The trees planted on Arbor Day show a concern for future generations. The simple act of planting a tree represents a belief that the tree will grow and some day provide wood products, wildlife habitat erosion control, shelter from wind and sun, beauty, and inspiration for ourselves and our children.

Trees provide us with benefits including serving as a sound barrier, stormwater abatement, and of course fresh air and oxygen

“It is well that you should celebrate your Arbor Day thoughtfully, for within your lifetime the nation’s need of trees will become serious. We of an older generation can get along with what we have, though with growing hardship; but in your full manhood and womanhood you will want what nature once so bountifully supplied and man so thoughtlessly destroyed; and because of that want you will reproach us, not for what we have used, but for what we have wasted.”

~Theodore Roosevelt, 1907 Arbor Day Message

by Sheila Dunning | Nov 9, 2018

As the trees begin to turn various shades of red, many people begin to inquire about the Popcorn trees. While their autumn coloration is one of the reasons they were introduced to the Florida environment, it took years for us to realize what a menace Popcorn trees have become. Triadica sebifera, the Chinese tallowtree or Popcorn tree, was introduced to Charleston, South Carolina in the late 1700s for oil production and use in making candles, earning it another common name, the Candleberry tree. Since then, it has spread to every coastal state from North Carolina to Texas, and inland to Arkansas. In Florida it occurs as far south as Tampa. It is most likely to spread to wildlands adjacent to or downstream from areas landscaped with Triadica sebifera, displacing other native plant species in those habitats. Therefore, Chinese tallowtree was listed as a noxious weed by the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services Noxious Weed List (5b-57.007 FAC) in 1998, which means that possession with the intent to sell, transport, or plant is illegal in the state of Florida. The common name of Florida Aspen is sometimes used to market Popcorn tree in mail-order ads. Remember it’s still the same plant.

As the trees begin to turn various shades of red, many people begin to inquire about the Popcorn trees. While their autumn coloration is one of the reasons they were introduced to the Florida environment, it took years for us to realize what a menace Popcorn trees have become. Triadica sebifera, the Chinese tallowtree or Popcorn tree, was introduced to Charleston, South Carolina in the late 1700s for oil production and use in making candles, earning it another common name, the Candleberry tree. Since then, it has spread to every coastal state from North Carolina to Texas, and inland to Arkansas. In Florida it occurs as far south as Tampa. It is most likely to spread to wildlands adjacent to or downstream from areas landscaped with Triadica sebifera, displacing other native plant species in those habitats. Therefore, Chinese tallowtree was listed as a noxious weed by the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services Noxious Weed List (5b-57.007 FAC) in 1998, which means that possession with the intent to sell, transport, or plant is illegal in the state of Florida. The common name of Florida Aspen is sometimes used to market Popcorn tree in mail-order ads. Remember it’s still the same plant.

Although Florida is not known for the brilliant fall color enjoyed by other northern and western states, we do have a number of trees that provide some fall color for our North Florida landscapes. Red maple, Acer rubrum, provides brilliant red, orange and sometimes yellow leaves. The native Florida maple, Acer floridum, displays a combination of bright yellow and orange color during fall. And there are many Trident and Japanese maples that provide striking fall color. Another excellent native tree is Blackgum, Nyssa sylvatica. This tree is a little slow in its growth rate but can eventually grow to seventy-five feet in height. It provides the earliest show of red to deep purple fall foliage. Others include Persimmon, Diospyros virginiana, Sumac, Rhus spp. and Sweetgum, Liquidambar styraciflua. In cultivated trees that pose no threat to native ecosystems, Crape myrtle, Lagerstroemia spp. offers varying degrees of orange, red and yellow in its leaves before they fall. There are many cultivars – some that grow several feet to others that reach nearly thirty feet in height. Also, Chinese pistache, Pistacia chinensis, can deliver a brilliant orange display.

Young Trident maple with fall foliage. Photo credit: Larry Williams

There are a number of dependable oaks for fall color, too. Shumardi, Southern Red and Turkey are a few to consider. These oaks have dark green deeply lobed leaves during summer turning vivid red to orange in fall. Turkey oak holds onto its leaves all winter as they turn to brown and are pushed off by new spring growth. Our native Yellow poplar, Liriodendron tulipifera, and hickories, Carya spp., provide bright yellow fall foliage. And it’s difficult to find a more crisp yellow than fallen Ginkgo, Ginkgo biloba, leaves. These trees represent just a few choices for fall color. Including one or several of these trees in your landscape, rather than allowing the Popcorn trees to grow, will enhance the season while protecting the ecosystem from invasive plant pests.

For more information on Chinese tallowtree, removal techniques and native alternative trees go to: http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/ag148.

by hollyober | Nov 9, 2018

The week prior to Halloween is officially designated as National Bat Week. In honor of this event, it’s worth considering some of the benefits bats provide to us.

Did you know there is a species of bat that lives nowhere in the world but within our state? It’s called the Florida Bonneted Bat, and occurs in only about 12-15 counties in south and central FL. These bats are so mysterious that we’re currently not even sure exactly where they occur. They are so rare that they’re listed as a federally endangered species.

The Florida Bonneted Bat lives nowhere in the world but Florida. Photo credits: Merlin Tuttle.

These bats were named for their forward-leaning ears, which they can tilt forward to cover their eyes. With a wingspan of 20 inches, they are the largest bats east of the Mississippi River: only two U.S. species are larger than they are, and these both occur out west.

We have been investigating the diet of Florida Bonneted Bats. To do this, we captured bats in specialized nets, and then collected their scat (called guano). Next, we processed the scat in a laboratory using DNA metabarcoding to determine which insect species the bats had recently consumed.

We found that the bats eat several economically important insects, including the following:

- fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda)

- lesser cornstalk borer (Elasmopalpus lignosellus)

- tobacco hornworm (Manduca sexta)

- black cutworm (Agrotis ipsilon)

These insects are pests of corn, cotton, peanut, soybean, sorghum, tobacco, tomato, potato, and many other crops.

Furthermore, the bats did not eat these insect pests infrequently. In fact, 86% of the samples we examined contained at least one pest species. On average, each sample contained three pest species! This tells us that Florida Bonneted Bats should be considered IPM (Integrated Pest Management) agents.

Currently, a new student has begun investigating the diets of bats more commonly found in northern Florida, southern Georgia, and southern Alabama. By the time Bat Week 2019 rolls around we’ll have details on which insect pests these bats could eat on your property.

If you’re interested in helping bats or incorporating them into your Integrated Pest Management efforts, consider creating roosts for them (places where the bats can sleep during the day). Bats roost not only in caves, but also in cavities in trees, in dead palm fronds, and in bat houses.

by Rick O'Connor | Aug 17, 2018

Being in the panhandle of Florida you may, or may not, have heard about the water quality issues hindering the southern part of the state. Water discharged from Lake Okeechobee is full of nutrients. These nutrients are coming from agriculture, unmaintained septic tanks, and developed landscaping – among other things. The discharges that head east lead to the Indian River Lagoon and other Intracoastal Waterways. Those heading west, head towards the estuaries of Sarasota Bay and Charlotte Harbor.

A large bloom of blue-green algae (cyanobacteria) in south Florida waters.

Photo: NOAA

Those heading east have created large algal blooms of blue-green algae (cyanobacteria). The blooms are so thick the water has become a slime green color and, in some locations, difficult to wade. Some of developed skin rashes from contacting this water. These algal blooms block needed sunlight for seagrasses, slow water movement, and in the evenings – decrease needed dissolved oxygen. When the algae die, they begin to decompose – thus lower the dissolved oxygen and triggering fish kills. It is a mess – both environmentally and economically.

On the west coast, there are red tides. These naturally occurring events happen most years in southwest Florida. They form offshore and vary in intensity from year to year. Some years beachcombers and fishermen barely notice them, other years it is difficult for people to walk the beaches. This year is one of the worst in recent memories. The increase in intensity is believed to be triggered by the increase in nutrient-filled waters being discharged towards their area.

Dead fish line the beaches of Panama City during a red tide event in the past.

Photo: Randy Robinson

On both coasts, the economic impact has been huge and the quality of life for local residents has diminished. Many are pointing the finger at the federal government who, through the Army Corp of Engineers, controls flow in the lake. Others are pointing the finger at shortsighted state government, who have not done enough to provide a reserve to discharge this water, not enforced nutrient loads being discharged by those entities mentioned above. Either way, it is a big problem that has been coming for some time.

As bad as all of this is, how does this impact us here in the Florida panhandle?

Though we are not seeing the impacts central and south Florida are currently experiencing, we are not without our nutrient discharge issues. Most of Florida’s world-class springs are in our part of the state. In recent years, the water within these springs have seen an increase in nutrients. This clouds the water, changing the ecology of these systems and has already affected glass bottom boat tours at some of the classic springs. There has also been a decline in water entering the springs due to excessive withdrawals from neighboring communities. The increase in nutrients are generally from the same sources as those affecting south Florida.

Florida’s springs are world famous. They attracted native Americans and settlers; as well as tourists and locals today.

Photo: Erik Lovestrand

Though we are not seeing large algal blooms in our local estuaries, there are some problems. St. Joe Bay has experienced some algal blooms, and a red tide event, in recent years that has forced the state to shorten the scallop season there – this obviously hurts the local economy. Due to stormwater runoff issues and septic tanks maintenance problems, health advisories are being issued due to high fecal bacteria loads in the water. Some locations in the Pensacola area have levels high enough that advisories must be issued 30% of the time they are sampled – some as often as 40%. Health advisories obviously keep tourists out of those waterways and hurt neighboring businesses as well as lower the quality of life for those living there.

Then of course, there is the Apalachicola River issue. Here, water that normally flows from Georgia into the river, and eventually to the bay, has been held back for water needs in Georgia. This has changed flow and salinity within the bay, which has altered the ecology of the system, and has negatively impacted one of the more successful seafood industries in the state. The entire community of Apalachicola has felt the impact from the decision to hold the water back. Though the impacts may not be as dramatic as those of our cousins in south Florida, we do have our problems.

Bay Scallop Argopecten iradians

http://myfwc.com/fishing/saltwater/recreational/bay-scallops/

What can we do about it?

The quick answer is reduce our nutrient input.

The state has adopted Best Management Practices (BMPs) for farmers and ranchers to help them reduce their impact on ground water and surface water contamination from their lands. Many panhandle farmers and ranchers are already implementing these BMPs and others can. We encourage them to participate. Read more at Florida’s Rangeland Agriculture and the Environment: A Natural Partnership – https://nwdistrict.ifas.ufl.edu/nat/2015/07/18/floridas-rangeland-agriculture-and-the-environment-a-natural-partnership/.

As development continues to increase across the state, and in the panhandle, sewage infrastructure is having trouble keeping up. This forces developments to use septic tanks. Many of these septic systems are placed in low-lying areas or in soils where they should not be. Others still are not being maintained property. All of this leads to septic leaks and nutrients entering local waterways. We would encourage local communities to work with new developments to be on municipal sewer lines, and the conversion of septic to sewer in as many existing septic systems as possible. Read more at Maintaining Your Septic Tank – https://nwdistrict.ifas.ufl.edu/nat/2017/04/29/maintain-your-septic-system-to-save-money-and-reduce-water-pollution/.

And then there are the lawns. We all enjoy nice looking lawns. However, many of the landscaping plans include designs that encourage plants that need to be watered and fertilized frequently as well as elevations that encourage runoff from our properties. Following the BMPs of the Florida Friendly Landscaping ProgramTM can help reduce the impact your lawn has on the nutrient loads of neighboring waterways. Read more at Florida Friendly Yards – https://nwdistrict.ifas.ufl.edu/nat/2018/06/08/restoring-the-health-of-pensacola-bay-what-can-you-do-to-help-a-florida-friendly-yard/.

For those who have boats, there is the Clean Boater Program. This program gives advice on how boaters can reduce their impacts on local waterways. Read more at Clean Boater – https://floridadep.gov/fco/cva/content/clean-boater-program.

One last snippet, those who live along the waterways themselves. There is a living shoreline program. The idea is return your shoreline to a more natural state (similar to the concept of Florida Friendly LandscapingTM). Doing so will reduce erosion of your property, enhance local fisheries, as well as reduce the amount of nutrients reaching the waterways from surrounding land. Installing a living shoreline will take some help from your local extension office. The state actually owns the land below the mean high tide line and, thus, you will need permission (a permit) to do so. Like the principals of a Florida Friendly Yard, there are specific plants you should use and they should be planted in a specific zone. Again, your county extension office can help with this. Read more at The Benefits of a Living Shoreline – https://nwdistrict.ifas.ufl.edu/nat/2017/10/06/the-benefits-of-a-living-shoreline/.

Though we may not be experiencing the dramatic problems that our friends in south Florida are currently experiencing, we do have our own problems here in the panhandle – and there is plenty we can do to keep the problems from getting worse. Please consider some of them. You can always contact your local county extension office for more information.

by Rick O'Connor | Aug 3, 2018

Of all the issues facing our local estuaries, high levels of fecal bacteria is the one that hinders commercial and recreational use the most. When bacteria levels increase and health advisories are issued, people become leery of swimming, paddling, or consuming seafood from these waterways.

Closed due to bacteria.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

I have been following the fecal bacteria situation in the Pensacola Bay system for several decades. Cheryl Bunch (Florida Department of Environmental Protection) has done an excellent job monitoring and reporting the bacteria levels, along with other parameters, for years – she has been fantastic.

The organisms used for monitoring have changed, so comparing numbers now and 30 years ago is somewhat difficult – but those changes came with good reason.

Fecal bacteria are organisms found in the large intestine of birds and mammals. They assist with digestion and are not a real threat to our health. Understanding that both birds and mammals in and near our estuaries must defecate, it is understandable that some levels of these bacteria are in the waterways. However, when levels are high there is a concern there are high levels of waste in the water. This waste can carry other organisms that can cause health problems for humans – such as hepatitis and cholera. So fecal bacteria monitoring is used as a proxy for other potential harmful organisms. No one wants to swim in sewage.

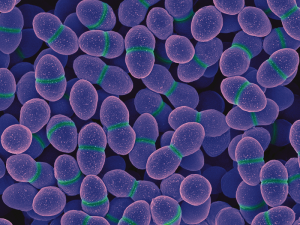

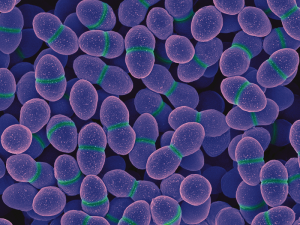

E. coli is a classic proxy for this type of monitoring and has been used for years. Recently it was found that saline water could kill some of the fecal bacteria – giving monitors’ low readings in estuarine systems – suggesting that there is little sewage in the water – when in fact there may be high levels of sewage undetected. They have found Enterococcus a better proxy for marine waters, particularly Enterococcus faecalis. Researchers have determined that a single sample of bay water should have more than 35 colonies of Enterococcus (ENT). If they find 35 or more colonies – a second sample is taken. If the counts are again high – a health advisory will be issued.

Over the last 30 years of monitoring FDEP’s reports on the Pensacola Bay area – there have been patterns. Most of the “hot spots” have been bayous and locations where rivers are discharging into an estuary. In addition, the periods of high fecal counts correspond well with periods of high rainfall. Locally, in the Pensacola Bay area, sampling has been reduced due to budget issues and some bodies of water are not sampled as often as others. Today both FDEP and the Florida Department of Health (FDOH) monitor and post their data via the Healthy Beaches Program. In this program, the sample stations are commonly used swimming areas – meaning some other locations are rarely, if ever, sampled. Based on these data, 30-40% of the samples from local bayous annually require a health advisory to be issued.

Health advisories can reduce interest in human related recreation activities, such as wakeboarding, paddling, or even fishing – and certainly impacts interest in swimming. Decades ago, swimming and skiing were very popular in local bayous. Today it is rare to see anyone doing so – most are motoring through heading to open bodies of water to spend their day. It may also be effecting property purchases. I have been contacted more than once with the question “would you buy on a house on XXX Bayou?”

Several local waterways are listed as impaired, and one is a BMAP area, due to high levels of bacteria. A BMAP (Basin Management Action Plan – read more at the link below) is a state designated body of water that is impaired (for some reason) and is required to make annual improvements to reduce the problem.

The spherical cells of the “coccus” bacteria Enterococcus.

Photo: National Institute of Health

So What Can We Do to Reduce This Problem?

In the Pensacola area, both the city and county have made efforts to modify and improve stormwater problems. Baffle boxes in east Pensacola have helped to reduce the amount of runoff entering the bayous and bays, thus reducing the frequency health advisories are being issued. That said, during heavy events the counts still increase – and rainfall seems to be increasing in the area in recent years. We will continue to monitor the frequency of advisories and post these on Sea Grant Notes through the Escambia County extension office each week.

From our side of the story (you and me) – anything you can do to reduce runoff will certainly help. Florida Friendly Landscaping techniques are a good start (see article on FFL posted below). Clean up after your pet, both in your yard and after walks – most people do… but not all. Septic systems have been a point of concern. If you have a septic system, maintain it (see article below on how). If the opportunity presents itself, you can move from septic to a sewer system. At many public places along the waterfront have signs asking everyone not to feed the birds. Congregating birds equals congregating bird feces and this can be a health issue.

Local and state governments are working to reduce the stormwater impacts on our local estuaries – which trigger other problems as well as high bacteria counts. Local residents and businesses can do the same.

References

Lewis, M.J., J.T. Kirschenfeld, T. Goodhart. 2016. Environmental Quality of the Pensacola Bay System: Retrospective Review for Future Resource Management and Rehabilitation. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Gulf Breeze FL. EPA/600/R-16/169.

BMAP

https://floridadep.gov/dear/water-quality-restoration/content/basin-management-action-plans-bmaps.

Florida Friendly Landscaping

Restoring the Health of Pensacola Bay, What You Can Do to Help? – Florida Friendly Landscaping

http://blogs.ifas.ufl.edu/escambiaco/2018/06/08/restoring-the-health-of-pensacola-bay-what-can-you-do-to-help-a-florida-friendly-yard/.

Septic Systems

Maintain Your Septic Tank System to Save Money and Reduce Water Pollution

https://nwdistrict.ifas.ufl.edu/nat/2017/04/29/maintain-your-septic-system-to-save-money-and-reduce-water-pollution/.

Septic Tanks: What You Should Do When a Flood Occurs

https://nwdistrict.ifas.ufl.edu/nat/2018/05/04/septic-systems-what-should-you-do-when-a-flood-occurs/.