by Rick O'Connor | Apr 30, 2020

Okay, this is a gamble.

I began this series to celebrate the year of the Gulf of Mexico – “Embracing the Gulf 2020”. The idea was to write about the habitats, creatures, economic impacts, and issues surrounding the “pond” that we live on. I did a few introductory articles and then jumped right into the animals. We began with the fun ones – fish, sea turtles, whales – and now we are in the more unfamiliar – invertebrates like sponges and jellyfish.

But worms? Really? Who wants to read about worms?

A classic flatworm is this lung fluke.

Photo: Kansas State University.

Well, there are a lot of them, and they are everywhere. You will find in many sediment samples that worms dominate. They also play an important role in the marine community. They are great scavengers, cleaning the environment, and an important source of food in the food chains of the more familiar animals. But they are gross and creepy. When we find worms, we think the environment is gross and creepy – and sometimes it is, remember they CLEAN THE ENVIRONMENT. But worse is that many are parasites. Yes… many of them are, and that is certainly gross and creepy. Flukes, tapeworms, hookworms, leeches, who wants to learn amore about those? Well, honestly, parasitism is an interesting way to find food and the story on how they do this is pretty interesting… and gross… and creepy. Let’s get started.

According to Robert Barnes’ 1980 book Invertebrate Zoology, there are at least 11 phyla of worms – it is a big group. We are not going to go over all of them, rather I will focus on what I call the “big three”: flatworms, roundworms, and segmented worms. We will begin with the most primitive, the flatworms.

As the name implies, these worms are flat. They are so because they are the last of what we call the “acoelomate” animals. Acoelomates are animals that lack an internal body cavity and, thus, have no true body organs – there is no where for them to go. So, they absorb what they need, and excrete, through special cells in their skin. To be efficient at this, they are flat – this increases the surface area in contact with the environment. There are three classes of flatworms – one free swimming, and two that are parasitic.

This colorful worm is a marine turbellarian.

Photo: University of Alberta

The free-swimming ones are called turbellarians. Most are very small, look like leaves, very colorful, and undulate as they swim near the bottom. They have “eye-like” cells called photophores that allow them to see light – they can then choose whether to move towards the dark or not. They have nerve cells but no true brain, and one only one opening to the digestive tract – that being the mouth, so they must eat and go to the bathroom through the same opening. Weirder yet, the mouth is usually in the middle of the body, not at the head end. Some are carnivorous feeding on small invertebrates, others prefer algae, others are scavengers (CLEANING THE OCEAN). They can reproduce by regenerating their bodies but most use sexually reproduction. They are hermaphrodites – being both male and female. They can fertilize themselves but more often seek out another worm. Fertilization is internal and they lay very few eggs.

The human liver fluke. One of the trematode flatworms that are parasitic.

Photo: University of Pennsylvania

The second group are called trematodes and they are the parasites we know as “flukes”. We have heard of liver flukes in livestock and humans, but there are marine versions as well. They have adhesive organs located at the near the mouth that help hold on, and a type of skin that protects them from their hosts’ defensive enzymes. They feed on cells, mucous, and sometimes blood – yep… gross and creepy. Some are attached outside of their hosts body (ectoparasites) others are attached to internal organs (endoparasites). The ectoparasites breath using oxygen (aerobic), endoparasites are anaerobic. Like their turbellarian cousins, they are hermaphroditic and use internal fertilization to produce eggs. They differ though in that they produce 10,000 – 100,000 eggs! Their primary host (the one they spend their adult life feeding on) is always a vertebrate, fish being the most common. However, their life cycle requires the hatching larva find an intermediate host where they go through their developmental growth before returning to a primary host. These intermediate host are usually invertebrates, like snails. The eggs are released with the fish feces – a swimming larva is released – enters a snail – begins part of the developmental growth – consumed by an arthropod (like a crab) – completes development – and the crab is consumed by the fish – wah-la. The adults are usually found in the gills/lungs, liver, or blood of the vertebrate hosts. Gross and creepy.

The famous tapeworm.

Photo: University of Omaha.

Better yet are the tapeworms. We have all heard of these. They are also all parasites, but all are endoparasites. Weirder, they do not have a digestive tract. Gross and creepy. Their heads are very tiny compared to their bodies and have either four sets of suckers, or hooks, to hold onto the digestive tract of their hosts (usually vertebrates). The head is actually round but the body is very flat and divided into squares called proglottids. Each proglottid gets larger as you move towards the tail and each possesses all of the reproductive material needed to produce new worms – they too are hermaphrodites. They also have a type of skin that protects them from the enzymes of their hosts. They also require an intermediate host to complete their life cycle so the proglottids will exit the hosts body via feces and complete the cycle similar to the trematodes.

I began this with a comment on how worms benefit the overall marine environment of the Gulf. It is hard to see that in these flatworms. They are either just another consumer out there, or nasty parasites others in the community must deal with. Well… we look at the roundworms next time and see what they have to offer.

Reference

Barnes, R. 1980. Invertebrate Zoology. Saunders College Press. Philadelphia, PA. pp. 1089.

by Rick O'Connor | Apr 17, 2020

I’d like to be a jellyfish… cause jellyfish don’t pay rent…

They don’t walk and they don’t talk with some Euro-trash accent…

Their just simple protoplasm… clear as cellophane

They ride the winds of fortune… life without a brain

These lyrics from Jimmy Buffett’s song Mental Floss sort of sums it up doesn’t it. The easy-going lifestyle of the jellyfish.

Everyone who visits the Gulf coast knows about these guys, but few people… very few… like them. For most, the term jellyfish signals “pain”, “fear”, and “death”. The purple flag is flying, and no one wants to enter the water. Folks from the Midwest call local hotels and condos asking, “when are the jellyfish going to be there?” It’s understandable. Who wants to spend their week vacation on the Gulf inside a hotel because you can’t go swimming?

I found this along the shore last winter. These are cannonball jellyfish.

I would almost (…almost) rather be diving with a shark than hundreds of jellyfish. When you spot them, they are everywhere. Quietly swarming like ghosts. You push them off and they appear to move towards you – almost like smoke from a campfire, you can’t get away.

They are creepy things. But amazing too!

As Mr. Buffett’s points out, they are simple “protoplasm”. Their body is primarily a jelly-like substance called mesoglea – and most of that is water. If you place a dead jellyfish on your dock and come back that afternoon, you will probably find just a “stain” of where it was – there is almost nothing to them.

The “bell” of the jellyfish is mostly mesoglea. Some jellyfish have thick layers of this, others much thinner. Some have a small flap of skin along the margins of the bell called the velum which they can undulate and swim – but they are not strong swimmers. If the tide is going out, swim as they may… their heading out also.

The bell shaped body of a jellyfish with numerous tentacles.

Many species of jellyfish have interesting markings within the bell. One has a white-colored structure that forms a 4-leaf clover. Another has red triangles all connecting at the center of the bell. For many, these structures are the ones that produce the gametes. Jellyfish reproduce sexually but are hermaphroditic – meaning they produce female eggs and male sperm in the same animal. There is no physical contact between animals, they just release the gametes into the ocean when they are in thick swarms and wah-la… new jellyfish – many new jellyfish.

On the bottom of the bell is a single opening that leads to a single pouch. This opening is the mouth, and the pouch is called the gastrovascular cavity. Jellyfish are predators – carnivores. There are no teeth, and most do not seek their prey – their prey finds them. Hanging from their bell are the tools of the killing trade, the part of this animal we do not like… the tentacles. Some tentacles can extend for several feet beyond the bell, others you can hardly notice them – but this is where the killing happens.

Along the tentacles there are small capsules called cnidoblasts which contain small cells called nematocyst. These nematocyst contain a coiled dart which at the end contains a drop of venom. There is a trigger associated with this cell. The jellyfish does not fire it – instead, the prey bumps the trigger and the nematocyst “fires”. The drop of venom is injected, along with the hundreds of other nematocysts along the tentacle the fish just bumped. This venom paralyzes the prey, other tentacles coil around it firing more nematocysts, and the tentacles retract towards the mouth – bingo… lunch.

This box jellyfish was found near NAS Pensacola in November of 2015.

Photo: Brad Peterman

Of course, the same happens when people bump into them. For us it is painful and unpleasant – but we are not consumed. That said, some species are quite painful. Some will force people to the hospital, and some have even killed people. The Box Jellyfish is the most notorious of these deadly ones. Known for their habits in Australia, there are at least two species found in the Gulf. The ones found here are not common, and there are no reported deaths, but they do exist. The Four-Handed is the one more widespread here. It actually has eyes, can detect predators and prey and swim towards or away from them, and the male fertilizes the female internally – not your typical jellyfish.

The more familiar painful one is the Portuguese Man-of-War. This creature is more like a sponge in that it is not just one creature but a large “condo” of many. Some cells are specialized in feeding, these are found on their long tentacles. Others specialize in reproduction; these are found near the blue colored air bag. They produce this blueish colored air bag which is exposed above the surface. The wind pushes on the bag like a sail and this moves the creature across the environment in search of food. Hanging from the bag are long tentacles which are made up of individuals whose stomachs are all connected. So, when one group of cells makes contact and kills a prey – they consume it and the tissue is moved through the connecting stomachs to feed the whole colony. To feed a whole colony, you need a big fish – to kill a big fish, you need a strong toxin, and they have it. These are VERY painful and have put people in the hospital, some have died. Some say that the Portuguese man-of-war is not a “true” jellyfish. This is true in the sense that they belong to a different class of jellyfish. There are three classes, the Scyphozoans being what we call the “true” jellyfish – Portuguese man-of-wars are not scyphozoans, but rather hydrozoans.

The colonial Portuguese man-of-war.

Photo: NOAA

Another interesting thing about jellyfish, is that they are all not jellyfish-like. As we just mentioned, there are two other classes and one other phylum of jellyfish-like animals. Hydrozoans and anthozoans are not your typical jellyfish. Rather than being bell-shaped and drifting in the ocean looking for food, they are attached to the seafloor and look more like flowers. Their tentacles are usually smaller but do contain nematocysts. Their toxin can be strong, some do eat fish, but most have a weaker toxin and feed on very small creatures – some only eat plankton. These would include the hydra, sea anemones, and the corals. As mentioned above, this also would include the Portuguese man-of-war.

Comb jellies are those jellies that drift in the currents and have no tentacles. We commonly collect them and toss them at each other. When I was growing up, we referred to them as “football jellies” because of this. The reason they do not sting is not because they do not have tentacles (some species do) but rather they do not have nematocyst and cannot. Rather they have special cells called colloblast that produce a drop of sticky glue at the end which they use to capture prey. Not having toxins, they cannot kill large prey but rather feed on smaller creatures like plankton and each other – they are cannibals. For this reason, they are in a whole different phylum.

The nonvenmous comb jelly.

Photo: Bryan Fluech

The jellyfish of the Gulf are a nuisance at times but are actually amazing creatures.

by Rick O'Connor | Apr 5, 2020

We began this series on the Gulf talking about the Gulf itself. We then moved to the big, more familiar – maybe more interesting animals, the vertebrates – birds, fish, etc. In this edition we shift to the invertebrates – the “spineless” animals of the Gulf of Mexico. Many of them we know from shell collecting along the beach, others are popular seafood choices, but most we know nothing about and rarely see.

A spineless Comb Jelly.

Florida Sea Grant

They are numerous, on diversity alone – making up 90% of the animal kingdom. They may leave remnants behind so that we know they are there. They may be right in front of our faces, but we do not know what we are looking at. They are incredibly important. Providing numerous nutrient transport, and transfer, in the ecosystem – that would otherwise not exist. They also provide a lot of ecological services that reduce toxins and waste. One source suggests there are over 30 different phyla and over one million species of invertebrates. In this series we will cover six major groups and we begin with the simplest of them all… the sponges.

For some, you may not know that sponges are actually alive. For others, you knew this but were not sure what kind of creature it was. Are they plants? Animals? Just a sponge?

The answer is animal. Yea…

We usually think of animals as having legs, running around, eating things and defecting in places – the kinds of things that make good animal planet shows.

Sponges… would not make a great animal planet show. What are you going to watch? They appear to be doing nothing. They sit on the ocean floor… and… well… that’s it, they sit on the ocean floor. But they actually do a lot.

A vase sponge.

Florida Sea Grant

They are considered animal because (a) their cells lack a cell wall – which plants have, and (b) they are heterotrophic… consumers… they have to hunt their food and cannot make it as plants do.

What do they eat?

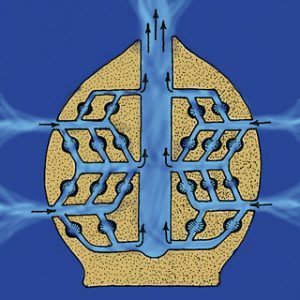

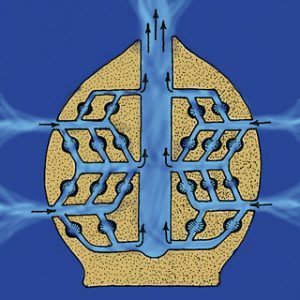

Plankton. Lots of plankton. Looking at a sponge you would call it one animal, but it is actually a colony of specialized cells working as a unit to survive. There are cells with flagella, called collar cells, that use these flagella to create currents that “suck” water into the body of the creature. This is how they collect plankton. The collar cells live in numerous channels throughout the sponge body connected to small pores all over the service of the sponge. This is where they get their phylum Porifera. As the water moves through the channels, the collar cells remove food and specialized cells called choanocytes release reproductive eggs called gemmules. All of the water eventually collects in a cavity, called the gastrovascular cavity where it exists the sponge through a large opening called an osculum.

This is how they eat and reproduce.

The anatomy of a sponge.

Flickr

The matrix, or tissue, of the sponge is held together by small, hard structures called spicules. It sort of serves as a skeleton for the creature. In different sponges the spicules are made of different materials, and this is how the creatures are divided into classes. Some are made of calcium carbonate, like seashells. Others are made of silica and are “glass-like”, and some made of a softer material called “spongin”, which are the ones we use to take baths with. Today purchased sponges are synthetic, not natural – but you can still get natural sponges.

Many sponges are tiny, others are huge. They all like seawater – not big fans of freshwater – and many produce mild toxins to defend the from predators. They do have predators though – hawksbill sea turtles love them. There is currently a lot of research going on using sponge toxins to kill cancer cells. Who knows, the cure to some forms of cancer may lie in the cavity of the sponge.

Another cool thing about them is that their cavities provide a lot of space for other small creatures in the ocean. Numerous species can be found in sponge tissue and cavities, utilizing this space as a habitat for themselves.

Florida Sea Grant

They are a major player in the development of reefs in the tropics and, like their counter parts coral, have experienced a decline due to over harvesting and harmful algal blooms. There are efforts in the Florida Keys to grow new sponge in aquaculture facilities and “re-plant” in the ocean. In the northern Gulf they are more associated with seagrass beds.

These are truly amazing creatures and the more we learn about them, the more amazing they become.

References:

Myriad World of the Invertebrates. EarthLife. https://www.earthlife.net/inverts/an-phyla.html.

by Rick O'Connor | Mar 9, 2020

When it comes to charismatic wildlife, there are few that are more than marine mammals. Everyone loves whales and dolphins. Even today, as many years as I have been working on the water, my colleagues and myself still get excited when we see dolphins. Seeing a whale is like a life-long bucket item. Marine mammals are pretty exciting to see.

A group of small dolphin leap from the ocean.

Photo: NOAA

In the world of marine mammals there are four different groups. Of course, there are the whales and dolphins (the cetaceans), there are the seals and sea lions (pinnipeds), the manatees (sirenians), and… believe it or not… the polar bear (ursids). But we only find two of these in the Gulf of Mexico. The polar bear, of course, does not live here. I know you needed to hear that from me. Pinnipeds no longer live here. Many may be surprised that there was once the Caribbean Monk Seal. There are records of this animal in the southern Gulf, but it is now extinct. There are records of California Sea Lions in the Gulf, possible release from some aquarium program – who knows, but no one has seen any in decades and it is believed they no longer exist here. So that leaves the cetaceans and the manatee.

The most recent publication (2017) states there are 28 species of cetaceans in the Gulf of Mexico. Cetaceans are subdivided into two groups: the baleen and the toothed whales. It is believed that 27 of the 28 species in the Gulf are toothed whales. Baleen whales are the big boys, 50-100’ in length and weighing tons. Some are the largest animals that ever existed on our planet. Most prefer cooler waters. Records of species come from whaling logs of the 19th and early 20th century as well as more recent scientific surveys and records from the Texas Marine Mammal Stranding Network. Early records suggest that right whales, humpbacks, sei, and even blue whales have been seen – though most of these were from the southern Gulf. But more recent science surveys indicated that only the Bryde’s Whale is encountered, and those are not common.

The majority are toothed whales. These would include the largest of them the sperm whale. Made famous in the novel Moby Dick, sperm whales were sought by whalers for their blubber and spermaceti. The blubber was boiled down to oil and used to light street lanterns and light houses. The spermaceti was used for a variety products including cosmetics. The sperm whales in the Gulf appear to be smaller than their counterparts in the open ocean and may be a separate subspecies. They seem to linger off the coast of Texas and Louisiana feeding on squid found at great depths.

The large head and double blowhole of a Bryde’s whale.

Photo: NOAA

Another toothed whale reported is the Orca, or killer whale. These are rare and are most often spotted in the central portion of the Gulf. There are numerous beaked whales and dolphins, but – though reported in early whaling logs – recent surveys suggest there are no porpoise. Porpoise differ from dolphin both in size and tooth shape. The most abundant dolphin is the pantropical spotted dolphin. Those who lived in the area in the 1980s and early 1990s might remember a stranding of dolphins that involved an adult female “Mango” and small baby named “Kiwi”. Mango died during recovery, but Kiwi lived for many years at the Gulfarium in Ft. Walton – these were pantropical spotted dolphins. The most familiar, and most often seen, are the Atlantic Bottlenose dolphins. These are a coastal species, many pods living within the estuary itself. They are the stars of many aquarium shows.

As you might guess, toothed whales are all carnivores. They only have canine teeth, so they must swallow their food whole. Their favorites are fish and squid. They have an amazing sense of echolocation that can help them navigate waters, detect prey, and even “stun” prey making it easier to eat. They give live birth as we do, and the calves stay with their mom for about two years learning how to survive. Cetaceans are very social forming groups known as pods. Most pods are dominated by females and young. Only one or two males are present.

A lone manatee spotted in Big Lagoon near Pensacola Pass. Sightings like these are becoming more common.

Photo: Marsha Stanton

Manatees are members of a group called Sirenia. This name comes from the fact that Columbus’ crew thought they were mermaids – “sirens of the sea”. It has been said before, that if they thought manatees were mermaids – their idea of a mermaid, and ours, is very different. That said, that is where they get their name. There are four species of sirenians on our planet, the one found here is the West Indian Manatee. They are found through the Caribbean, South Atlantic, and Gulf of Mexico. It is believed now that there are two subspecies – the Antillean of the Caribbean, and the Florida manatee from our neck of the woods. These are slow moving herbivores who can tolerate freshwater. They have a low tolerance for cold water and seek warm water springs, and the warm water discharges from power plants, during the winter.

Manatees are not as social as cetaceans and are usually not found in large groups unless they gather in warm water spots. Females usually give birth to a single calf which stays with her for about two years. They have flat molars, like cows, and feed on a variety of plants – the source of their other common name… “sea cows”. The numbers of these animals have increased in recent decades, but they are still low, and the animal is still protected. Boat strikes is one of the leading causes of death, though red tide, and cold stunning are also problems. Sightings of these animals in our area are increasing and we are currently tracking encounters at the county extension office. If you see one, please contact Rick O’Connor at the Escambia County Extension Office – (850) 475-5230, or roc1@ufl.edu.

Though the days of “Save the Whales” and “Save the Manatee” are not as common, these animals still face low numbers and problematic encounters with humans. Fishing gear, boat strikes, sounds, all take marine mammals in the Gulf each year. Hopefully we all get to check off seeing one of these magnificent creatures from our bucket list before the end of our time.

Resource:

Wursig, B. 2017. Marine Mammals of the Gulf of Mexico. In: Wards, C. (ed.) Habitats and Biota of the Gulf of Mexico: Before Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill. Springer, New NY.

by Rick O'Connor | Feb 13, 2020

An eastern cottonmouth basking near a creek in a swampy area of Florida.

Photo: Tommy Carter

When you think of reptiles you typically think of tropical rainforest or the desert. However, there is at least one member of the three orders of reptiles that do live in the sea. Saltwater crocodiles are found in the Indo-Pacific region as are about 50 species of sea snakes. There is one marine lizard, the marine iguana of the Galapagos Islands, and then the marine (or sea) turtles. These are found worldwide and are the only true marine reptiles found in the Gulf of Mexico.

Sea turtles are very charismatic animals and beloved by many. Five of the seven species are found in the Gulf. These include the Loggerhead, which is the most common, the Green, the Hawksbill, the Leatherback, and the rarest of all – the Kemp’s Ridley.

Many in our area are very familiar with the nesting behavior of these long-ranged animals. They do have strong site fidelity and navigate across the Gulf, or from more afar, to their nesting beaches – many here in the Pensacola Beach area. The males and females court and mate just offshore in early spring. The females then approach the beach after dark to lay about 100 eggs in a deep hole. She then returns the to the Gulf never to see her offspring. Many females will lay more than one clutch in a season.

The largest of the sea turtles, the leatherback.

Photo: Dr. Andrew Colman

The eggs incubate for 60-70 days and their temperature determines whether they will be male or female, warmer eggs become females. The hatchlings hatch beneath the sand and begin to dig out. If they detect problems, such as warm sand (we believe meaning daylight hours) or vibrations (we believe meaning predators) they will remain suspended until those potential threats are no more. The “run” (all hatchlings at once) usually occurs under the cover of darkness to avoid predators. The hatchlings scramble towards the Gulf finding their way by light reflecting off the water. Ghost crabs, fox, raccoon, and other predators take almost 90% of them, and the 10% who do reach the Gulf still have predatory birds and fish to deal with. Those who make it past this gauntlet head for the Sargassum weed offshore to begin their lives.

These are large animals, some reaching 1000 pounds, but most are in the 300-400 pound range, and long lived, some reaching 100 years. It takes many years to become sexually mature and typically long-lived / low reproductive animals are targets for population issues when disasters or threats arise. Many creatures eat the small hatchings, but there are few predators on the large reproducing adults. However, in recent years humans have played a role in the decline of the adult population and all five species are now listed as either threatened or endangered and are protected in the U.S. There are a couple of local ordinances developed to adhere to federal law requiring protection. One is the turtle friendly lighting ordinance, which is enforced during nesting season (May 1 – Oct 31), and the Leave No Trace ordinance requiring all chairs, tents, etc. to be removed from the beach during the evening hours. There are other things that locals can do to help protect these animals such as: fill in holes dug on the beach during the day, discard trash and plastic in proper receptacles, avoid snagging with fishing line and (if so) properly remove, and watch when boating offshore to avoid collisions.

If we include the barrier islands there are more coastal reptiles beyond the sea turtles. There are freshwater ponds which can harbor a variety of freshwater turtles. I have personally seen cooters, sliders, and even a snapping turtle on Pensacola Beach. Many coastal islands harbor the terrestrial gopher tortoise and wooded areas could harbor the box turtles. In the salt marsh you may find the only brackish water turtle in the U.S., the diamondback terrapin. These turtles do nest on our beaches and are unique to see. Freshwater turtle reproductive cycles are very similar to sea turtles, albeit most nest during daylight hours.

An American Alligator basking on shore.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

The American alligator can also be found in freshwater ponds, and even swimming in saltwater. They can reach lengths of 12 feet, though there are records of 15 footers. These animals actually do not like encounters with humans and will do their best to avoid us. Problems begin when they are fed and loose that fear. I have witnessed locals in Louisiana feeding alligators, but it is a felony in Florida. Males will “bello” in the spring to attract females and ward off competing males. Females will lay eggs in a nest made of vegetation near the shoreline and guard these, and the hatchlings, during and after birth. They can be dangerous at this time and people should avoid getting near.

We have several native species of lizards that call the islands home. The six-lined race runners and the green anole to name two. However, non-native and invasive lizards are on the increase. It is believed there are actually more non-native and invasive lizards in Florida than native ones. The Argentina Tegu and the Cuban Anole are both problems and the Brown Anole is now established in Gulf Breeze, East Hill, and Perdido Key – probably other locations as well. Growing up I routinely find the horned lizard in our area. I was not aware then they were non-native, but by the 1970s you could only find them on our barrier islands, and today sightings are rare.

An eastern cottonmouth crossing a beach.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

Then there are the snakes.

Like all reptiles, snakes like dry xeric environments like barrier islands. We have 46 species in the state of Florida, and many can be found near the coast. Though we have no sea snakes in the Gulf, all of our coastal snakes are excellent swimmers and have been seen swimming to the barrier islands. Of most concern to residents are the venomous ones. There are six venomous snakes in our area and four of them can be found on barrier islands. These include the Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake, the Pygmy Rattlesnake, the Eastern Coral Snake, and the Eastern Cottonmouth. There has been a recent surge in cottonmouth encounters on islands and this could be due to more people with more development causing more encounters, or there may be an increase in their populations. Cottonmouths are more common in wet areas and usually want to be near freshwater. Current surveys are trying to determine how frequently encounters do occur.

Not everyone agrees, but I think reptiles are fascinating animals and a unique part of the Gulf biosphere. We hope others will appreciate them more and learn to live with and enjoy them.

by Rick O'Connor | Jan 29, 2020

If you ask a kid who is standing on the beach looking at the open Gulf of Mexico “what kinds of creatures do you think live out there?” More often than not – they would say “FISH”.

And they would not be wrong.

According the Dr. Dickson Hoese and Dr. Richard Moore, in their book Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico, there are 497 species of fishes in the Gulf. However, they focused their book on the fish of the northwestern Gulf over the continental shelf. So, this would not include many of the tropical species of the coral reef regions to the south and none of the mysterious deep-sea species in the deepest part of the Gulf. Add to this, the book was published in 1977, so there have probably been more species discovered.

Schools of fish swim by the turtle reef off of Grayton Beach, Florida. Photo credit: University of Florida / Bernard Brzezinski

Fish are one of the more diverse groups of vertebrates on the planet. They can inhabit freshwater, brackish, and seawater habitats. Because all rivers lead to the sea, and all seas are connected, you would think fish species could travel anywhere around the planet. However, there are physical and biological barriers that isolate groups to certain parts of the ocean. In the Gulf, we have two such groups. The Carolina Group are species found in the northern Gulf and the Atlantic coast of the United States. The Western Atlantic Group are found in the southern Gulf, Caribbean, and south to Brazil. The primary factors dictating the distribution of these fish, and those within the groups, are salinity, temperature, and the bottom type.

Off the Texas coast there is less rain, thus a higher salinity; it has been reported as high 70 parts per thousand (mean seawater is 35 ppt). The shelf off Louisiana is bathed with freshwater from two major rivers and salinities can be as low as 10 ppt. The Florida shelf is more limestone than sand and mud. This, along with warm temperatures, allow corals and sponges to grow and the fish assemblages change accordingly.

Some species of fish are stenohaline – meaning they require a specific salinity for survival, such as seahorses and angelfish. Euryhaline fish are those who have a high tolerance for wide swings in salinity, such as mullet and croaker.

Courtesy of Florida Sea Grant. In total, it takes about 3 – 5 years for reefs to reach a level of maximum production for both fish and invertebrate species.

Forty-three of the 497 species are cartilaginous fish, lacking true bone. Twenty-five are sharks, the other 18 are rays. Sharks differ from rays in that their gill slits are on the side of their heads and the pectoral fins begins behind these slits. Rays on the other hand have their gill slits on the bottom (ventral) side of their body and the pectoral begins before them. Not all rays have stinging barbs. The skates lack them but do have “thorns” on their backs. The giant manta also lacks barbs.

Sharks are one of the more feared animals on the planet. 13 the 25 species belong to the requiem shark family, which includes bull, tiger, and lemon sharks. There are five types of hammerheads, dogfish, and the largest fish of all… the whale shark; reaching over 40 feet. The most feared of sharks is the great white. Though not believed to be a resident, there are reports of this fish in the Gulf. They tend to stay offshore in the cooler waters, but there are inshore reports.

The impressive jaws of the Great White.

Photo: UF IFAS

There is great variety in the 472 species of bony fishes found in the Gulf. Sturgeons are one of the more ancient groups. These fish migrate from freshwater, to the Gulf, and back and are endangered species in parts of its range. Gars are a close cousin and another ancient “dinosaur” fish. Eels are found here and resemble snakes. As a matter of fact, some have reported sea snakes in the Gulf only to learn later they caught an eel. Eels differ from snakes in having fins and gills. Herring and sardines are one of the more commercially sought-after fish species. Their bodies are processed to make fish meal, pet food, and used in some cosmetics. There are flying fish in the Gulf, though they do not actually fly… they glide – but can do so for over 100 yards. Grouper are one of the more diverse families in the Gulf and are a popular food fish across the region. There untold numbers of tropical reef fish. Surgeons, triggerfish, angelfish, tangs, and other colorful fish are amazing to see. Stargazers are bottom dwelling fish that can produce a mild electric shock if disturbed. Large billfish, such as marlins and sailfins, are very popular sport fish and common in the Gulf. Puffers are fish that can inflate when threatened and there are several different kinds. And one of the strangest of all are the ocean sunfish – the Mola. Molas are large-disk shaped fish with reduced fins. They are not great swimmers are often seen floating on their sides waiting for potential prey, such as jellyfish.

We could go on and on about the amazing fish of the Gulf. There are many who know them by fishing for them. Others are “fish watchers” exploring the great variety by snorkeling or diving. We encourage to take some time and visit a local aquarium where you can see, and learn more about, the Fish of the Gulf.

Reference

Hoese, H.D., R.H. Moore. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M University Press. College Station Texas. Pp. 327.