by Rick O'Connor | Jun 28, 2019

Or just mullet… maybe you prefer “mu-lay”…

Either way it is a fish we all know and love. Those of us who grew up here on the Gulf coast know this fish as part of our culture. I remember numerous family gatherings where fried mullet was the order of the day. Along with grits, baked beans, cole slaw, and iced tea you had your “mullet plate”. It is the fish of choice for Catholic fish fries during Lent. It is the icon of the “Mullet Toss” event at the Flora-Bama, which draws huge crowds and people plan for all year. It almost became the mascot of minor league baseball team. One my favorites was a story told to me by a colleague who used to teach at the old Booker T. Washington High School when it was on “A” street. He told me each morning the janitorial staff would catch mullet for the school lunches. They would have your classic “mullet plate” for lunch everyday – fresh from the bay – how good is that. It is the fish that “jumps” and everyone knows what it is.

The Striped Mullet.

Image: LSU Extension

I paddle area waters monitoring a variety of things assessing the health status of Pensacola Bay. While out there I see a lot of wildlife, but mullet is one of the more common ones. Wherever I go, open intracoastal waterway, grassbeds, bayous, marshes, even backwater creeks where the water is almost stagnant, I find mullet. You see their swirls, schools gliding beneath your paddleboard or kayak, I even watched one make unusual circles with its head above water once. And always the “jump”, they are always jumping. But I had never really thought much about their biology. Many folks observe and study more unusual, or problematic fish, like lionfish. But the mullet slips by the radar. It is more like… “oh yea, then there is the mullet”, and we do not think of them more than that.

Local recreational and commercial fishermen are aware of their movements and behaviors. They know when and where they will be at different times of the year. But I thought I would do some digging and educate the rest of you about this amazing fish who is like part of the family.

There are actually two species of mullet swimming in area waters. The striped mullet (Mugil cephalus) is more common. It is one that the commercial fishermen seek, FWC lists as the “black mullet” on their commercial guides. The other is the white mullet (Mugil curema). They differ in that the anal fin of the white mullet has 9 soft rays; the striped has 8. Large striped mullet will have stripes, which the large white mullet lack. The juveniles of both species lack stripes. When caught and still alive, the white mullet will have a bright gold spot on the operculum (the bone covering the gills), this is lacking on the striped mullet.

A fisherman throws a cast net to catch mullet at White Point in Choctawhatchee Bay

Mullet are euryhaline… meaning they can tolerate a wide range of salinities and can be found in fresh or saltwater. They travel in schools, feeding off of the bottom. Their diet consists of bacteria and single-celled algae found attached to plants. They pick at the bottom, and scrape seagrasses consuming these.

They spawn most of the year, but the peak is between October and December. Spawning takes place in the open Gulf of Mexico, sometimes far offshore. They become sexual mature at three years old and can produce 0.5 – 4 million eggs. Mullet roe (fish eggs) is a local delicacy for some. They have been reported at an age of 16 years – long time for a fish.

While studying marine biology in college, I remember someone asked our professor why mullet jump. He paused for several seconds and then replied – “for the same reason manta rays jump”… there was a long pause… so we bit the bait – “okay, why do manta rays jump?” “We don’t know”. Classic…

However, they now have an idea why. It is believed they clean their gills doing this and also oxygenate those gills in stagnant, warm, low oxygen waters that mullet find themselves in periodically.

A striped mullet died during cold stress.

It is a local commercial fishery. Between 2018-2019 412,421 pounds of mullet were landed in Escambia County, another 151,638 pounds in Santa Rosa. This made it the number one fish for the season. Between the two counties the value of the fishery was $456,892 but sells better as a bait than as food.

It is truly a magnificent fish. Their numbers have increased since the 1995 net ban and has become one of the more common fish we see while exploring local estuarine waters. I certainly will not take them for granted any longer.

by Laura Tiu | May 3, 2019

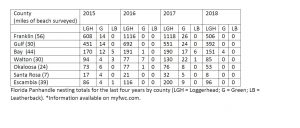

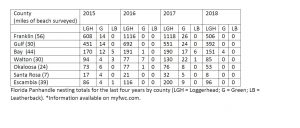

There are five species of sea turtles that nest from May through August on Florida beaches, with hatching stretching out until October. The loggerhead, the green turtle, and the leatherback all nest regularly in the Panhandle, with the loggerhead being the most frequent visitor. Two other species, the hawksbill and Kemp’s Ridley nest infrequently. All five species are listed as either threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act. Due to their threatened and endangered status, the Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission/Fish and Wildlife Research Institute monitors sea turtle nesting activity on an annual basis.

A group checks out a recently hatched sea turtle nest on the dunes in south Walton county in Florida.

Annual total nest counts for loggerhead sea turtles on Florida’s index beaches fluctuate widely and scientists do not yet understand fully what drives these changes. From 2011 to 2018, an average of 106,625 sea turtle nests (all species combined) were recorded annually on these monitored beaches. In 2018, there was a slight decrease in nests with only 96,945 nests recorded statewide. This is not a true reflection of all of the sea turtle nests each year in Florida, as it doesn’t cover every beach, but it gives a good indication of nesting trends and distribution of species.

2015-2018 Florida Panhandle turtle nesting totals for all species.

If you want to see a sea turtle in the Florida Panhandle, please visit one of the state-permitted captive sea turtle facilities listed below, admission fees may be charged. Please call the number listed for more information.

- Gulf Specimen Marine Laboratory

222 Clark Dr

Panacea, FL 32346

850-984-5297

Admission Fee

- Gulf World Marine Park

15412 Front Beach Rd

Panama City, FL 32413

850-234-5271

Admission Fee

- Gulfarium Marine Adventure Park

1010 Miracle Strip Parkway SE

Fort Walton Beach, FL 32548

850-243-9046 or 800-247-8575

Admission Fee

- Navarre Beach Sea Turtle Center

8740 Gulf Blvd

Navarre, FL 32566

850-499-6774

The Foundation for The Gator Nation. An Equal Opportunity Institution

by Laura Tiu | Jan 31, 2019

They say that dreams don’t work unless you take action. In the case of some Walton County Florida dreamers, their actions have transpired into the first Underwater Museum of Art (UMA) installation in the United States. In 2017, the Cultural Arts Alliance of Walton County (CAA) and South Walton Artificial Reef Association (SWARA) partnered to solicit sculpture designs for permanent exhibit in a one-acre patch of sand approximately .7-miles from the shore of Grayton Beach State Park at a depth of 50-60 feet. The Museum gained immediate notoriety and has recently named by TIME Magazine as one of 100 “World’s Greatest Places.” It has also been featured in online and print publications including National Geographic, Lonely Planet, Travel & Leisure, Newsweek, The New York Times, and more.

Seven designs were selected for the initial installation in summer of 2018 including: “Propeller in Motion” by Marek Anthony, “Self Portrait” by Justin Gaffrey, “The Grayt Pineapple” by Rachel Herring, “JYC’s Dream” by Kevin Reilly in collaboration with students from South Walton Montessori School, “SWARA Skull” by Vince Tatum, “Concrete Rope Reef Spheres” by Evelyn Tickle, and “Anamorphous Octopus” by Allison Wickey. Proposals for a second installation in the summer of 2019 are currently being evaluated.

The sculptures themselves are important not only for their artistic value, but also serve as a boon to eco-tourism in the area. While too deep for snorkeling, except perhaps on the clearest of days, the UMA is easily accessible by SCUBA divers. The sculptures are set in concrete and contain no plastics or toxic materials. They are specifically designed to become living reefs, attracting encrusting sea life like corals, sponges and oysters as well large numbers and varieties of fish, turtles and dolphins. This fulfills SWARA’s mission of “creating marine habitat and expanding fishery populations while providing enhanced creative, cultural, economic and educational opportunities for the benefit, education and enjoyment of residents, students and visitors in South Walton.”

The UMA is a diver’s dream and is in close proximity to other Walton County artificial reefs. There are currently four near-shore snorkel reefs available for snorkeling and nine reefs within one mile of the shore in approximately 50-60 feet of water for additional SCUBA opportunities. All reefs are public and free of charge for all visitors with coordinates available on the SWARA website (https://swarareefs.org/). Several SCUBA businesses in the area offer excursions to UMA and the other reefs of Walton County.

For more information, please visit the UMA website at https://umafl.org/ or connect via social media at https://www.facebook.com/umaflorida/.

Schools of fish swim by the turtle reef off of Grayton Beach, Florida. Photo credit: University of Florida / Bernard Brzezinski

by Rick O'Connor | Sep 2, 2018

Most kids who grew up on the Gulf Coast grew up catching blue crabs. These animals are common along our shorelines, relatively easy to catch, and adventurous because they may bite you. I caught my first one in 1965 and we proudly displayed the boiled shell over the kitchen bar for many years. This is also a popular seafood target with an estimated commercial landing value of $56,950 in the Pensacola Bay area in 2017.

Blue crabs are one of the few crabs with swimming appendages.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

But who is this crab that we enjoy so much? What do we know about it?

As you probably already know, it is one of an estimated 30,000 species of arthropods we call crustaceans. Crustaceans differ from insects and arachnids in that they have five pairs of legs and two sets of antenna. Insects typically have a head, thorax, and abdomen – however, in the crustaceans the head and thorax are fused into what is called a cephlathorax and covered with a section of the shell called the carapace. Like all arthropods, their body are completely covered in a chitinous shell that serves as their exoskeleton. This exoskeleton must be periodically shed (molting) so they can continue to grow. Crustaceans tend to molt about 10-11 times each year and typically in the summer months. To molt, crustaceans will remove some of the salts and minerals from the shell into their tissue, this weakens the shell enough to separate it. The crack is usually between the cephlathorax and abdomen. When they emerge, they are completely soft and about 30% larger than before – it is amazing to see this large crab emerge from the small shell it once lived in. Because of the softness of the body after molting, this is usually done under the cover of darkness for protection. The salts and minerals it removed during pre-molting are now used to harden the new shell – which can take a couple of days. It is at this stage we call them “soft shells”.

The crustaceans include many different kinds of arthropods – most notably are the crabs, shrimps, and lobsters. There are over 4500 species of crabs and they differ from shrimps and lobsters in the fact their abdomen flexes beneath their body – you do not see the “tail” you see in a lobster or shrimp – but its there. Crabs can also move very well laterally, which their cousins are not so good. Blue crabs differ from other crabs in that their last pair of legs are modified as paddles and the animal can swim. They can swim forwards, backwards, and laterally – and they are often seen swimming at the surface. There are other crabs who have these swimming paddles and they are all called protunid crabs.

Blue crabs perceive their world through their eyes, antenna, and sensory cells on their body. They are very good at burying in the sand – eyes and antenna exposed – and sensory cells all working – seeking prey and avoiding predators. Their eyes differ from ours in that they have numerous lenses, compared to our single one, and are called compound eyes. Each lens does not provide them with an image of you or me however. Rather each lenses provides them with a single pixel of light. It is much like the image you see on television when they are trying to block out a brand name, or someone’s face. The more pixels (lenses) you have, the clearer the image. Those this type of eye does not give as clear an image as ours; it is very good at detecting motion and has served the arthropods very well over the years.

For blue crabs, food can be just about anything. They are active hunters – usually using the ambush method of capture (buried in the sand), but are also known scavengers – eating any bits of food they can find. Those enjoy crabbing know this – you can put just about anything as bait in a crab trap and it works. They have numerous predators including fish, birds, mammals, and sea turtles.

Male and female blue crabs.

Photo:

Blue crabs can be found in a variety of salinities (euryhaline). Males are typically found in the lower salinities of the upper bay. Females join them during mating season – which is in late spring and summer. Males cradle the females beneath his legs for several days waiting for the right location and moment to breed. Fishermen refer to them as “doublers” during this time. The females will molt and the male will then deposit his sperm into a sac called a spermatophore – which he then deposits to the female. She will then migrate to the more saline lower portions of the lower bay, while he remains and seeks another female. This may be the only spermatophore she receives her entire life – which can be up to five years, though most do not live beyond three years. She will use sperm from this spermatophore over that time to fertilize eggs.

The eggs develop in a sponge mass that develops beneath her abdomen. This egg mass is orange when in early development and becomes a darker brown with age as the larvae consume the yolk. There can be between 750,000 and 2,000,000 developing eggs within this mass. The females are called gravid at this stage and it is illegal to harvest gravid crabs in Florida.

The eggs hatch in about two weeks and a small microscopic mosquito looking larvae emerges – at this stage, they are called zoea. The zoea drift into the Gulf of Mexico where they feed and molt. Eventually they return to the estuary and become a microscopic crab with a tail – this stage is called a megalops. The megalops will feed and molt. The tail will eventually flex beneath and the crab becomes sexually mature. The entire process from hatching to sexual maturity is about 12-18 months.

These are fascinating animals. They are very common and a large part of the coastal culture of the Florida panhandle. Kids will have great fun catching them with a hand net, letting them swim in their beach buckets, but be sure to let them go before you head home and watch those claws – they do know how to use them. It is a great animal.

The famous blue crab.

Photo: FWC

Recreational Blue Crab Harvest Regulations in Florida

No size limit

10 gallons whole / harvester / day

Harvesting gravid females is prohibited

Five crab traps / person – cannot be placed in navigation channels

Trap closed season in Florida panhandle – Jan 5-14 in odd years.

References

Barnes, R.D. 1980. Invertebrate Zoology. Saunders College Press. Philadelphia PA. pp. 1089.

Blue Crab. Callinectes sapidus. Chesapeake Bay Program. 2018. https://www.chesapeakebay.net/discover/field-guide/entry/blue_crab.

Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. Commercial Landings in Florida. 2017-2018. http://myfwc.com/research/saltwater/fishstats/commercial-fisheries/landings-in-florida/.

Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. Recreational Blue Crabbing. http://myfwc.com/fishing/saltwater/recreational/blue-crab/.

by Laura Tiu | Aug 3, 2018

Written By: Laura Tiu, Holden Harris, and Alexander Fogg

Non-containment lionfish traps being tested by the University of Florida offshore Destin, FL. Invasive lionfish are attracted to the lattice structure, then captured by netting when the trap is pulled from the sea floor. The trap may have the potential to control lionfish densities at depths not accessible by SCUBA divers. [ALEX FOGG/CONTRIBUTED PHOTO]

Red lionfish (Pterois volitas / P. miles) are a popular aquarium fish with striking red and white strips and graceful, butterfly-like fins. Native to the Indo-Pacific region, lionfish were introduced into the wild in the mid-1980s, likely from the release of pet lionfish into the coastal waters of SE Florida. In the early 2000s lionfish spread throughout the US eastern seaboard and into the Caribbean, before reaching the northern Gulf of Mexico in 2010. Today, lionfish densities in the northern Gulf are higher than anywhere else in their invaded range.

Invasive lionfish negatively affect native reef communities. They consume and compete with native reef fish, including economically important snappers and groupers. Their presence has shown to drive declines in native species and diversity. Lionfish possess 18 venomous spines that appear to deter native predators. The interaction of invasive lionfish with other reef stressors – including ocean acidification, overfishing, and pollution – is of concern to scientists.

Lionfish harvest by recreational and commercial divers is currently the best means of controlling their densities and minimizing their ecological impacts. Lionfish specific spearfishing tournaments have proven successful in removing large amounts in a relatively short amount of time. This year’s Lionfish Removal and Awareness Day removed almost 15,000 lionfish from the Northwest Florida waters in just two days. Lionfish is considered to be an excellent quality seafood, and they are now being targeted by a handful of commercial divers. Several Florida restaurants, seafood markets, and grocery stores chains are now regularly serving lionfish.

While diver removals can control localized lionfish densities, the problem is that lionfish also inhabit reefs much deeper than those that can be accessed by SCUBA divers. Surveys of deepwater reefs show lionfish have higher densities and larger body sizes than lionfish on shallower reefs. In the Gulf of Mexico, the highest densities of lionfish surveyed were between 150 – 300 feet. While SCUBA diving is typically limited to less than 130 feet, lionfish have been observed deeper than 1000 feet.

For the past several years, researchers have been working to develop a trap that may be able to harvest lionfish from deep water. Dr. Steve Gittings, Chief Scientist for the Office of National Marine Sanctuaries at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, has spearheaded the design for a “non-containment” lionfish trap. The design works to “bait” lionfish by offering a structure that attracts them. The trap remains open while deployed on the sea floor, allowing fish to move in and out of the trap footprint. When the trap is retrieved, a netting is pulled up around

Deep water lionfish traps being tested by the University of Florida offshore Destin, FL. [ALEX FOGG/CONTRIBUTED PHOTO]

The researchers are headed offshore to retrieve, redeploy, and collect data on the lionfish traps. Twelve non-containment traps are currently being tested offshore NW Florida. The research is supported by a grant from the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. The study will try to answer important questions for a new method of catching lionfish: where and how can the traps be most effective? How long should they be deployed? And, is there any bycatch (accidental catch of other species)?

Recent trials have proved successful in attracting lionfish to the trap with minimal bycatch. Continued research will hone the trap design and assess how deployment and retrieval methods may increase their effectiveness. If successful in testing, lionfish traps may become permitted for use by commercial and recreational fisherman. The traps could become a key tool in our quest to control this invasive species and may even generate income while protecting the deepwater environment.

Outreach and extension support for the UF’s lionfish trap research is provided by Florida Sea Grant. For more information contact Dr. Laura Tiu, Okaloosa and Walton Counties Sea Grant Extension Agent, at lgtiu@ufl.edu / 850-689-5850 (Okaloosa) / 850-892-8172 (Walton).

by Rick O'Connor | May 31, 2018

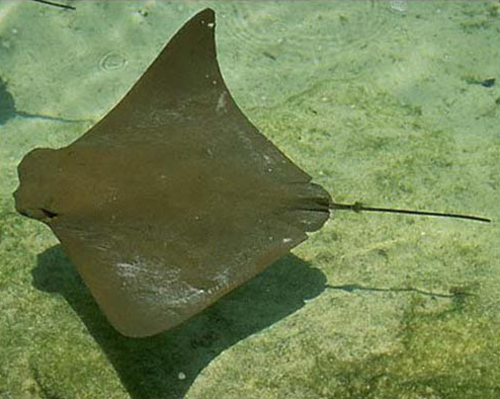

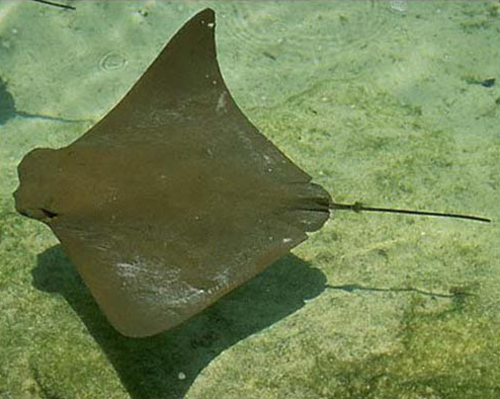

It is now late May and in recent weeks I, and several volunteers, have been surveying the area for terrapins, horseshoe crabs, and monitoring local seagrass beds. We see many creatures when we are out and about; one that has been quite common all over the bay has been the “stingray”.

The cownose ray is often mistaken for the manta ray. It lacks the palps (“horns”) found on the manta.

Photo: Florida Sea Grant

These are intimidating creatures… everyone knows how they can inflict a painful wound using the spine in their tail, but may are not aware that not all “stingrays” can actually use a spine to drive you off – actually, not all “rays” are “stingrays”.

So what is a ray?

First, they are fish – but differ from most fish in that they lack a bony skeleton. Rather it is cartilaginous, which makes them close cousins of the sharks.

So what is the difference between a shark and a ray?

You would immediately jump on the fact that rays are flat disked-shape fish, and that sharks are more tube-shaped and fish like. This is probably true in most cases, but not all. The characteristics that separate the two groups are

- The five gill slits of a shark are on the side of the head – they are on the ventral side (underside) of a ray

- The pectoral fin begins behind the gill slits in sharks, in front of for the ray group

Not all rays have the whip-like tail that possess a sharp spine; some in fact have a tube-shaped body with a well-developed caudal fin for a tail.

There are eight families and 19 species of rays found in the Gulf of Mexico. Some are not common, but others are very much so.

Sawfish are large tube-shaped rays with a well-developed caudal fin. They are easily recognized by their large rostrum possessing “teeth” giving them their common name. Walking the halls of Sacred Heart Hospital in Pensacola, you will see photos of fishermen posing next to monsters they have captured. Sawfish can reach lengths of 18 feet… truly intimidating. However, they are very slow and lethargic fish. They spend their lives in estuaries, rarely going deeper than 30 feet. They were easy targets for fishermen who displayed them as if they caught a true monster. Today they are difficult to find and are protected. There are still sightings in southwest Florida, and reports from our area, but I have never seen one here. I sure hope to one day. There are two species in the Gulf of Mexico.

Guitarfish are tube-shaped rays that are very elongated. They appear to be sharks, albeit their heads are pretty flat. They more common in the Gulf than the bay and, at times, will congregate near our reefs and fishing piers to breed. They are often confused with the electric rays called torpedo rays, but guitarfish lack the organs needed to deliver an electric shock. They have rounded teeth and prefer crustaceans and mollusk to fish. There is only one species in the Gulf.

Torpedo rays can deliver an electric shock – about 35 volts of one. Though there are stories of these shocking folks to death, I am not aware of any fatalities. Nonetheless, the shock can be serious and beach goers are warned to be cautious. I once mistook one buried in the sand for a shell. Let us just say the jolt got my attention and I may have had a few words for this fish before I returned to the beach. We have two species of torpedo rays in the Gulf of Mexico.

Skates look JUST like stingrays – but they lack the whip-like tail and the venomous spine that goes with it. They are very common in the inshore waters of the Florida Panhandle and though they lack the terrifying spine we are all concerned about, they do possess a series of small thorn-like spine on the back that can be painful to the bare foot of a swimmer. Skates are famous for producing the black egg case folks call the “mermaids’ purse”. These are often found dried up along the shore of both the Gulf and they bay and popular items to take home after a fun day at the beach. There are four species of skates found in the Gulf of Mexico.

Stingrays… this is the one… this is the one we are concerned about. Stingrays can be found on both sides of our barrier islands and like to hide beneath the sand to ambush their prey. More often than not, when we approach they detect this and leave. However, sometimes they will remain in the sand hoping not to be detected. The swimmer then steps on their backs forcing them to whip their long tail over and drive the serrated spine into your foot. This usually makes you move off them – among other things. The piercing is painful and spine (which is actually a modified tooth) possesses glands that contain a toxic substance. It really is no fun to be stung by these guys. Many people will do what is called the “stingray shuffle” as they move through the water. This is basically sliding your feet across the sand reducing your chance of stepping on one. They are no stranger to folks who visit St. Joe Bay. The spines being modified teeth can be easily replaced after lodging in your foot. Actually, it is not uncommon to find one with two or three spines in their tails ready to go. Stingrays do not produce “mermaids’ purses” but rather give live birth. There are five species in the Gulf of Mexico.

The Atlantic Stingray is one of the common members of the ray group who does possess a venomous spine.

Photo: Florida Museum of Natural History

Butterfly ray is a strange looking fish and easy to recognize. The wide pectoral fins and small tail gives it the appearance of a butterfly. Despite the small tail, it does possess a spine. However, the small tail makes it difficult for the butterfly ray to pierce you with it. There is only one species in the Gulf, the smooth butterfly ray.

Eagle rays are one of the few groups of rays that actually in the middle of the water column instead of sitting on the ocean floor. They can get quite large and often mistaken for manta rays. Eagle rays lack the palps (“horns”) that the manta ray possesses. Rather they have a blunt shaped head and feed on mollusk. They do have venomous spines but, as with the butterfly ray, their tails are too short to extend and use it the way stingrays do. There are two species. The eagle ray is brown and has spots all over its back. The cownose ray is very common and almost every time I see one, I hear “there go manta rays”… again, they are not mantas. They have a habit of swimming in the surf and literally body surfing. Surfers, beachcombers, and fishermen frequently see them.

Last but not least is the very large Manta ray. This large beast can reach 22 feet from wingtip to wing tip. Like eagle rays, they swim through the ocean rather than sit on the bottom. They have to large “horns” (called palps) that help funnel plankton into their mouths. These horns give them one of their common names – the devilfish. Mantas, like eagle and butterfly rays, do have whip-like tails and a venomous spine, but like the above, their tails are much shorter and so effective placement of the spine in your foot is difficult.

Many are concerned when they see rays – thinking that all can inflict a painful spine into your foot – but they are actually really neat animals, and many are very excited to see them.

References

Hoese, H.D., R.H. Moore. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M. College Station, TX. pp. 327.

Shipp, R. L. 2012. Guide to Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico. KME Seabooks. Mobile AL. pp. 250.