by Les Harrison | Sep 28, 2018

The Wacissa River offers paddlers the opportunity to see north Florida unfiltered.

Being off the beaten path has many advantages. In the case of a spring-fed river, it translates to less pressure from human use and a great opportunity for those who do visit to experience the “real Florida”.

The Wacissa River, located in the southern half of Jefferson County, Florida, is near the crossroads identified as the town of Wacissa. There is a blinking light, a post office, and two small convenience stores where beer, ice and snacks can be purchased.

Access to the river is about two miles south of the blinking light on Florida 59, just after the state road veers to the southwest. The blacktop spur quickly become a dirt parking lot after passing several canoe and kayak rental businesses.

A county maintained boat landing with pick-nic tables, a manmade beach, and a tiny diving platform with a rope swing are the only signs of civilization. The cold, clear water extends to a tree line several hundred yards south of the landing with the river moving to the southeast.

The river emerges crystal clear from multiple limestone springs along the first mile and a half of the 12 mile waterway. The adjacent land is flat and subject to being swampy, especially in wet years like 2018.

The river terrain stands in contrast to the Cody Scarp just a few miles to the north. This geologic feature is the remnants of an ancient marine terrace and is hilly, rising 100 feet above the river in some spots.

Cypress, oak, pine, and other trees cover the bottomlands adjacent to the river. The river quickly enters the Aucilla Wildlife Management Area which results in a wide variety of animals, birds, amphibians and reptiles.

The wildlife viewing varies by season. Many migratory birds use the river’s shelter and resources on their annual trips.

Canoeing and kayaking are popular in the gentle current. Powerboats and fan boats can use the area also, but must be on constant alert for shallow spots and hidden snags.

For the adventurous paddler who wants to follow the river’s course, there is a debarkation point at Goose Pasture Campgrounds and another near St. Marks after the Wacissa merges with the Aucilla.

Be prepared when taking this journey. This is the real Florida, no fast food restaurants or convenience stores. Only clear water, big trees and the calls of birds will be found here.

by Judy Biss | Sep 14, 2018

Bumble bees and other pollinators often visit the vast fields of cotton flowers in north Florida’s agricultural lands. Although cotton is mainly self-pollinating, pollination by bees can increase seed-set per cotton boll. Note the pollen grains stuck on each bee. Photo by Judy Biss

Beekeeping is thriving in Panhandle Florida and the importance of honeybee health and pollination is frequently in the news. As much as 1/3 of our food supply depends on the pollinating activities of honeybees, and because of this fact, pollinator protection was formally recognized at the federal level in 2014 when the President of the United States signed the memorandum called: Creating a Federal Strategy to Promote the Health of Honey Bees and Other Pollinators.

The goals of this policy are to increase and improve pollinator habitat for not only managed European honeybee colonies, but also native bees, birds, bats, and butterflies – all of which are vital to our nation’s economy, food production, and environmental health.

So, of the variety of pollinating insects and animals, what are some of Florida’s native pollinating bees? What do they look like and what are their characteristics? Let’s take a look at a few. Follow the links provided for additional, fascinating details. I will start with one of my favorites, because it happens to pollinate one of my favorite fruits. Blueberries!

The Southeastern blueberry bee uses buzz pollination on a blueberry plant. Photo credit: UF/IFAS Photo by Tyler Jones.

While managed honeybees can pollinate blueberries, the Southeastern blueberry bee, as well as bumblebees, are much more efficient pollinators of this crop. These bees “sonicate” the flowers to release more pollen. Sonication, or buzz pollination is caused by the bee’s high-speed wing beats vibrating the flower causing pollen to fall onto the bee. As we will see with many of our native bees, the Southeastern Blueberry bee is a solitary bee meaning it does not live in colonies like the European honeybee. The Southeastern Blueberry bee digs burrows in the ground where they lay eggs that hatch the following year to start the cycle over again.

Male blue orchard bee. Males have long antennae. Credit: Kevin Hall, BugGuide.net

Blue orchard bees are native to the United States and Canada, and are important pollinators of a variety of fruits including blueberries. They are solitary bees most active in the early spring and summer. They are part of a group of bees called mason bees that use holes or tube-like structures to nest in. Some garden supply stores now carry native bee nesting cavities such as stacks of bamboo or blocks of wood with holes of varying sizes that you can use to attract these native pollinators to your backyard.

Many native pollinating bees, such as the mason bees, are solitary in nature and can be attracted to your backyard by providing nesting habitat. Bee nesting “houses,” such as this block of wood with pre-drilled holes, are available for sale more frequently now in garden supply stores. Note the cavities that were used indicated by the mud-like plugs. Photo by Judy Biss

Nesting area of the miner bee, Anthophora abrupta Say. Photograph by Jason Graham, University of Florida.

A few years ago, our office received a call about a number of bees flying around a large pile of fill dirt in one of our local parks. It turned out to be the nesting site of these fascinating bees. These bees are solitary, yet gregarious. Solitary in that the female builds her own burrow in the ground in which to lay her egg; gregarious in that they tend to congregate together to build their individual burrows. They are pollinators of a number of plants, including fruits and vegetables.

Adult female Anthophora abrupta Say, a miner bee. Photograph by Katie Buckley, University of Florida.

Bumble bees are among the most recognizable of insects. They are large, colorful, and a wonder to watch. They are also important pollinators of both native plants and agricultural crops. Bumble bees are so effective at pollinating important food crops, they are raised commercially and sold to pollinate produce such as tomatoes, peppers, cranberries, and strawberries. Blueberries and other commercially important food crops benefit from the bumblebees’ ability to “sonicate,” or “buzz pollinate,” as described above. They are social bees forming small colonies (50 – 500 individuals) in the ground or empty cavities, which only last one season.

Leafcutting bees are a group of important native pollinators found throughout the world, including North America. In Florida, there are approximately 63 different species of leafcutting bees, one of which is Osmia lignaria listed above (Blue Orchard Bee). As the name implies, these solitary bees cut neat circles from broadleaf deciduous plants which they use to build their long tubular nests. While their leaf cutting capabilities can sometimes decrease the esthetics of some common landscape plants, their actions will not harm the plants. They are pollinators of wildflowers and many of our fruits and vegetables.

Typical leaf damage caused by leafcutting bees, Megachile spp. The bees use the leaf pieces to construct nests. Photograph by L.J. Buss, University of Florida.

Sweat bees are important pollinators for many wildflowers and fruits and vegetables, including peaches, plums, apples, pears, alfalfa and sunflower. This family of bees (Halictidae) contains one of the largest genera of bees in the world, displaying a wide range of social, nesting, physical, and foraging characteristics. In Florida, there are 44 species of sweat bees.

So, the next time you are walking in the garden, or hiking in Florida’s beautiful woodlands and pastures, slow down to catch of glimpse of these busy and critically important insect pollinators. I for one am quite grateful for those bees that help produce an abundance of food… especially blueberries!

For more information, check out the following resources:

Calhoun County Florida Wasps and Flies

Love Blueberries? Thank the Blueberry Bee!

USDA Forest Service publication: “Bee Basics—An Introduction to our Native Bees,”

UF/IFAS Entomology and FDACS Featured Creatures

The Bumble Bee – One of Florida’s Vital Pollinators

Blue Orchard Bee, Osmia lignaria Say (Insecta: Hymenoptera: Megachilidae)

by Shep Eubanks | Sep 12, 2018

North Florida buck feeding on acorns at the edge of a food plot. Photo Credit – Shep Eubanks UF/IFAS

It’s that time of year when landowners, hunters, and other wildlife enthusiasts begin to plan and prepare fall and winter food plots to attract wildlife like the nice buck in the photo.

Annual food plots are expensive and labor intensive to plant every year and with that thought in mind, an option you may want to consider is planting mast producing crops around your property to improve your wildlife habitat. Mast producing species are of two types of species, “hard mast” (oaks, chestnut, hickory, chinkapin, American Beech, etc.), and “soft mast” (crabapple, persimmon, grape, apple, blackberry, pears, plums, pawpaws, etc.). There are many mast producing trees and shrubs that can be utilized and will provide food and cover for a variety of wildlife species. This article will focus on two, sawtooth oak (or other oaks) and southern crabapple.

Sawtooth Oak

Oaks are of tremendous importance to wildlife and there are dozens of species in the United States. In many areas acorns comprise 25 to 50% of a wild turkeys diet in the fall (see photos 1, 2, and 3) and probably 50% of the whitetail deer diet as well during fall and winter. White oak acorns average around 6% crude protein versus 4.5% to 5% in red oak acorns. These acorns are also around 50% carbohydrates and 4% fat for white oak and 6% fat for red oak.

The Sawtooth Oak is in the Red Oak family and typically produces acorns annually once they are mature. The acorns are comparable to white oak acorns in terms of deer preference as compared to many other red oak species. Most red oak acorns are high in tannins reducing palatability but this does not seem to hold true for sawtooth oak. They are a very quick maturing species and will normally begin bearing around 8 years of age. The acorn production at maturity is prolific as you can see in the photo and can reach over 1,000 pounds per tree in a good year when fully mature. They can reach a mature height of 50 to 70 feet. There are two varieties of sawtooth oak, the original sawtooth and the Gobbler sawtooth oak, which has a smaller acorn that is better suited for wild turkeys. The average lifespan of the sawtooth oak is about 50 years

Photo 1 – Seventeen year old planting of sawtooth oaks in Gadsden County Florida. Photo Credit – Shep Eubanks UF/IFAS

Photo 2 – Gadsden County gobblers feeding on Gobbler sawtooth oak acorns

Photo Credit – Shep Eubanks UF/IFAS

Photo 3 – Gobbler sawtooth oak acorns in Gadsden County. Notice the smaller size compared to the regular sawtooth oak acorn which is the size of a white oak acorn.

Photo credit – Shep Eubanks UF/IFAS

Southern Crabapple

Southern Crabapple is one of 25 species of the genus Malus that includes apples. They generally are well adapted to well drained but moist soils and medium to heavy soil types. They will grow best in a pH range of 5.5 – 6.5 and prefer full sun but will grow in partial shade as can be seen in photo 4. They are very easy to establish and produce beautiful blooms in March and April in our area as seen in photo 5. There are many other varieties of crabapples such as Dolgo that are available on the market in addition to southern and will probably work very well in north Florida. The fruit on southern crabapple is typically yellow green to green and average 1 to 1.5 inches in diameter. They are relished by deer and normally fall from the tree in early October.

Photo 4 – Southern crabapple tree planted on edge of pine plantation stand. Photo taken in late March during bloom.

Photo credit – Shep Eubanks UF/IFAS

Photo 5 – Showy light pink to white bloom of southern crabapple in early April during bloom.

Photo credit – Shep Eubanks UF/IFAS

A good resource publication on general principles related o this topic is Establishing and Maintaining Wildlife Food Sources.

If you are interested in planting traditional fall food plots check out this excellent article by UF/IFAS Washingon Couny Extension Agent Mark Mauldin: Now’s the Time to Start Preparing for Cool-Season Food Plots .

For more information on getting started with food plots in your county contact your county’s UF/IFAS Extension Office

by Laura Tiu | Aug 3, 2018

Written By: Laura Tiu, Holden Harris, and Alexander Fogg

Non-containment lionfish traps being tested by the University of Florida offshore Destin, FL. Invasive lionfish are attracted to the lattice structure, then captured by netting when the trap is pulled from the sea floor. The trap may have the potential to control lionfish densities at depths not accessible by SCUBA divers. [ALEX FOGG/CONTRIBUTED PHOTO]

Red lionfish (Pterois volitas / P. miles) are a popular aquarium fish with striking red and white strips and graceful, butterfly-like fins. Native to the Indo-Pacific region, lionfish were introduced into the wild in the mid-1980s, likely from the release of pet lionfish into the coastal waters of SE Florida. In the early 2000s lionfish spread throughout the US eastern seaboard and into the Caribbean, before reaching the northern Gulf of Mexico in 2010. Today, lionfish densities in the northern Gulf are higher than anywhere else in their invaded range.

Invasive lionfish negatively affect native reef communities. They consume and compete with native reef fish, including economically important snappers and groupers. Their presence has shown to drive declines in native species and diversity. Lionfish possess 18 venomous spines that appear to deter native predators. The interaction of invasive lionfish with other reef stressors – including ocean acidification, overfishing, and pollution – is of concern to scientists.

Lionfish harvest by recreational and commercial divers is currently the best means of controlling their densities and minimizing their ecological impacts. Lionfish specific spearfishing tournaments have proven successful in removing large amounts in a relatively short amount of time. This year’s Lionfish Removal and Awareness Day removed almost 15,000 lionfish from the Northwest Florida waters in just two days. Lionfish is considered to be an excellent quality seafood, and they are now being targeted by a handful of commercial divers. Several Florida restaurants, seafood markets, and grocery stores chains are now regularly serving lionfish.

While diver removals can control localized lionfish densities, the problem is that lionfish also inhabit reefs much deeper than those that can be accessed by SCUBA divers. Surveys of deepwater reefs show lionfish have higher densities and larger body sizes than lionfish on shallower reefs. In the Gulf of Mexico, the highest densities of lionfish surveyed were between 150 – 300 feet. While SCUBA diving is typically limited to less than 130 feet, lionfish have been observed deeper than 1000 feet.

For the past several years, researchers have been working to develop a trap that may be able to harvest lionfish from deep water. Dr. Steve Gittings, Chief Scientist for the Office of National Marine Sanctuaries at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, has spearheaded the design for a “non-containment” lionfish trap. The design works to “bait” lionfish by offering a structure that attracts them. The trap remains open while deployed on the sea floor, allowing fish to move in and out of the trap footprint. When the trap is retrieved, a netting is pulled up around

Deep water lionfish traps being tested by the University of Florida offshore Destin, FL. [ALEX FOGG/CONTRIBUTED PHOTO]

The researchers are headed offshore to retrieve, redeploy, and collect data on the lionfish traps. Twelve non-containment traps are currently being tested offshore NW Florida. The research is supported by a grant from the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. The study will try to answer important questions for a new method of catching lionfish: where and how can the traps be most effective? How long should they be deployed? And, is there any bycatch (accidental catch of other species)?

Recent trials have proved successful in attracting lionfish to the trap with minimal bycatch. Continued research will hone the trap design and assess how deployment and retrieval methods may increase their effectiveness. If successful in testing, lionfish traps may become permitted for use by commercial and recreational fisherman. The traps could become a key tool in our quest to control this invasive species and may even generate income while protecting the deepwater environment.

Outreach and extension support for the UF’s lionfish trap research is provided by Florida Sea Grant. For more information contact Dr. Laura Tiu, Okaloosa and Walton Counties Sea Grant Extension Agent, at lgtiu@ufl.edu / 850-689-5850 (Okaloosa) / 850-892-8172 (Walton).

by Sheila Dunning | Jul 23, 2018

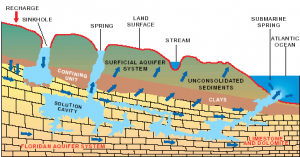

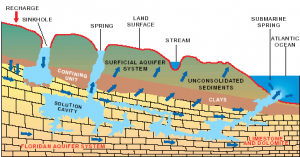

Hydrologic cycle and geologic cross-section image courtesy of Florida Geological Survey Bulletin 31, updated 1984.

With more than 250 crystal clear springs in Northwest Florida it is just a short road trip to a pristine swimming hole! Springs and their associated flowing water bodies provide important habitat for wildlife and plants. Just as importantly, springs provide people with recreational activities and the opportunity to connect with the natural environment. While paddling your kayak, floating in your tube, or just wading in the cool water, think about the majesty of the springs. They are the visible part of the Florida Aquifer, the below ground source of most Florida’s drinking water.

A spring is a natural opening in the Earth where water emerges from the aquifer to the soil surface. The groundwater is under pressure and flows upward to an opening referred to as a spring vent. Once on the surface, the water contributes to the flow of rivers or other waterbodies. Springs range in size from small seeps to massive pools. Each can be measured by their daily gallon output which is classified as a magnitude. First magnitude springs discharge more than 64.6 million gallons of water each day. Florida has over 30 first magnitude springs. Four of them can be found in the Panhandle – Wakulla Springs and the Gainer Springs Group of 3.

Wakulla Springs is located within Edward Ball Wakulla Springs State Park. The spring vent is located beneath a limestone ledge nearly 180 feet below the land surface. Archaeological evidence suggests that humans have utilized the area for nearly 15,000 years. Native Americans referred to the area as “wakulla” meaning “river of the crying bird”. Wakulla was the home of the Limpkin, a rare wading bird with an odd call.

Over 1,000 years ago, Native Americans used another first magnitude spring, the Gainer Springs group that flow into the Econfina River. “Econfina”, or “natural bridge” in the local native language, got its name from a limestone arch that crossed the creek at the mouth of the spring. General Andrew Jackson and his Army reportedly used the natural bridge on their way west exploring North America. In 1821, one of Jackson’s surveyors, William Gainer, returned to the area and established a homestead. Hence, the naming of the waters as Gainer Springs.

Three major springs flow at 124.6 million gallons of water per day from Gainer Springs Group, some of which is bottled by Culligan Water today. Most of the springs along the Econfina maintain a temperature of 70-71°F year-round. If you are in search of something cooler, you may want to try Ponce de Leon Springs or Morrison Springs which flows between 6.46 and 64.6 million gallons a day. They both stay around 67.8°F. Springs are very cool, clear water with such an importance to all living thing; needing appreciation and protection.

by Andrea Albertin | May 4, 2018

Special care needs to be taken with a septic system after a flood or heavy rains. Photo credit: Flooding in Deltona, FL after Hurricane Irma. P. Lynch/FEMA

Approximately 30% of Florida’s population relies on septic systems, or onsite sewage treatment and disposal systems (OSTDS), to treat and dispose of household wastewater. This includes all water from bathrooms and kitchens, and laundry machines.

When properly maintained, septic systems can last 25-30 years, and maintenance costs are relatively low. In a nutshell, the most important things you can do to maintain your system is to make sure nothing but toilet paper is flushed down toilets, reduce the amount of oils and fats that go down your kitchen sink, and have the system pumped every 3-5 years, depending on the size of your tank and number of people in your household.

During floods or heavy rains, the soil around the septic tank and in the drain field become saturated, or water-logged, and the effluent from the septic tank can’t properly drain though the soil. Special care needs to be taken with your septic system during and after a flood or heavy rains.

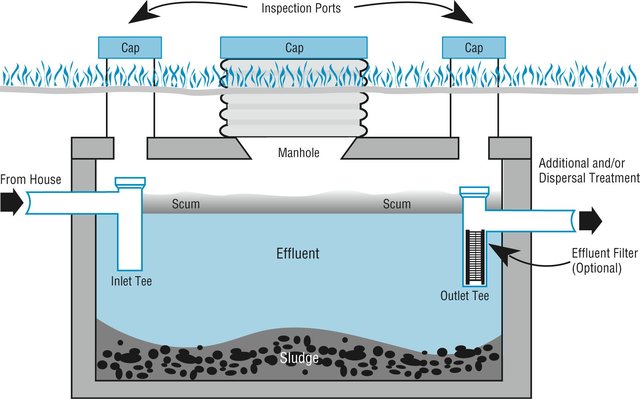

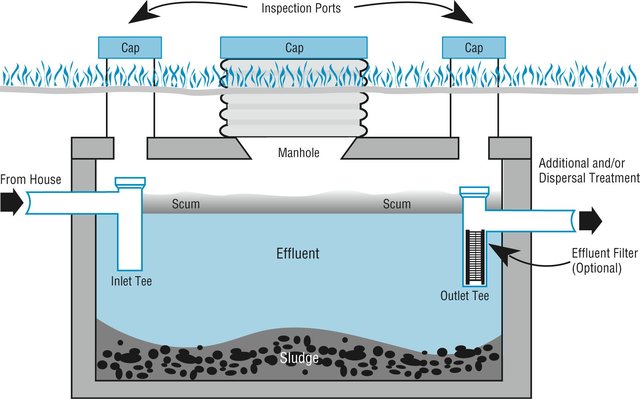

Image credit: wfeiden CC by SA 2.0

How does a traditional septic system work?

The most common type of OSTDS is a conventional septic system, made up of (1) a septic tank (above), which is a watertight container buried in the ground and (2) a drain field, or leach field. The effluent (liquid wastewater) from the tank flows into the drain field, which is usually a series of buried perforated pipes. The septic tank’s job is to separate out solids (which settle on the bottom as sludge), from oils and grease, which float to the top and form a scum layer. Bacteria break down the solids (the organic matter) in the tank. The effluent, which is in the middle layer of the tank, flows out of the tank and into the drain field where it then percolates down through the ground.

During floods or heavy rains, the soil around the septic tank and in the drain field become saturated, or water-logged, and the effluent from the septic tank can’t properly drain though the soil. Special care needs to be taken with your septic system during and after a flood or heavy rains.

What should you do after flooding occurs?

- Relieve pressure on the septic system by using it less or not at all until floodwaters recede and the soil has drained. For your septic system to work properly, water needs to drain freely in the drain field. Under flooded conditions, water can’t drain properly and can back up in your system. Remember that in most homes all water sent down the pipes goes into the septic system. Clean up floodwater in the house without dumping it into the sinks or toilet.

- Avoid digging around the septic tank and drain field while the soil is water logged. Don’t drive heavy vehicles or equipment over the drain field. By using heavy equipment or working under water-logged conditions, you can compact the soil in your drain field, and water won’t be able to drain properly.

- Don’t open or pump out the septic tank if the soil is still saturated. Silt and mud can get into the tank if it is opened, and can end up in the drain field, reducing its drainage capability. Pumping under these conditions can also cause a tank to pop out of the ground.

- If you suspect your system has been damage, have the tank inspected and serviced by a professional. How can you tell if your system is damaged? Signs include: settling, wastewater backs up into household drains, the soil in the drain field remains soggy and never fully drains, and/or a foul odor persists around the tank and drain field.

- Keep rainwater drainage systems away from the septic drain field. As a preventive measure, make sure that water from roof gutters doesn’t drain into your septic drain field – this adds an additional source of water that the drain field has to manage.

More information on septic system maintenance after flooding can be found on the EPA website publication https://www.epa.gov/ground-water-and-drinking-water/septic-systems-what-do-after-flood

By taking special care with your septic system after flooding, you can contribute to the health of your household, community and environment.