Where Did All of the Shrimpers Go?

I recently saw a news clip about a new Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation (FWC) ruling for shrimpers. I was interested in this new ruling but also asked the question – “Where did all of the shrimpers go?”

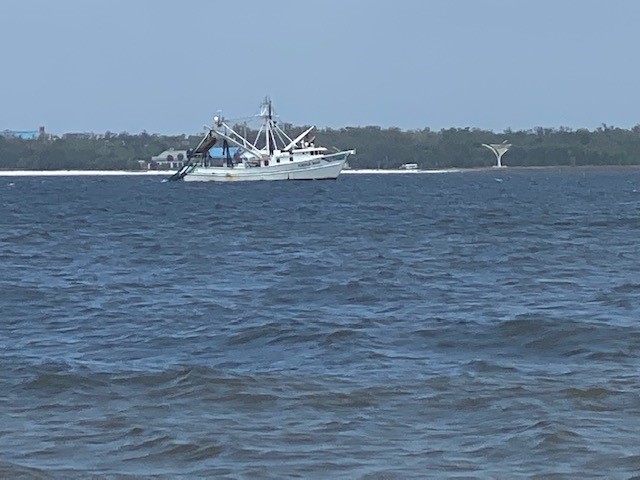

What I mean by this is that when I was young there were shrimp boats on Pensacola Bay every evening. They seemed to trawl one side of the Pensacola Bay Bridge or the other, but you could see the lights on the decks of each trawler and there were many, looking like front porch lights of a small community, all over the bay. In the morning they would head towards the seawall along both sides of Palafox Street near the old Pensacola Municipal Auditorium and sell from the boats. We made frequent trips there.

Then the boats stopped coming to the docks…

And the Municipal Auditorium is now gone also…

The focus turned to the docks near Joe Patti’s. Joe Patti’s, American, and Allen Williams Seafood companies were places we would frequent to purchase shrimp when they came in. Then those slowly disappeared with only Joe Patti’s remaining open to the public. The shrimp boats still come to the docks of Allen Williams, but in fewer numbers and the shrimp began to go through Joe Patti’s, Maria’s, Perdido and other seafood markets. Now the lights on the bay at night are few. Actually, I rarely see them anymore. Where did they go?

As you look at the commercial landings of shrimp since 1980 you see some interesting trends.

First, understand that commercial landings mean this is where the shrimpers “land” their catch, not where they caught it.

Second, that brown shrimp (bay shrimp) are BY FAR the most landed species in Escambia County. Comparing brown shrimp to white (also called Gulf shrimp), rock shrimp, and royal reds, there was a total of 13,372,791 lbs. of brown shrimp landed between 1984 and 2019. For the others white shrimp was 255,587 lbs., royal reds 95,920 lbs., and rock shrimp 78,817 lbs. You could also say the same for effort. Between 1984-2019 there were 31,935 trips for brown shrimp, 904 for white shrimp, 143 for rock shrimp, and only 19 for royal reds. So, brown shrimp are king for commercial landings here.

Third, there were 1000 or more trips per year for brown shrimp until 2002. That year it dropped to 835. In 2003 that was cut in half to 453 and the trend continued to decline. Between 2017-2019 there were less than 100 trips each year. There is a similar pattern for white shrimp. Prior to 2002 the number of trips for white shrimp were in the double digits, occasionally in the triple, each year. In 2002 it dropped from 38 to 7 per year and never recovered. Though royal reds and rock shrimp were never big players in local landings, between 2010 and 2019 there was only one trip for rock shrimp and no trips were logged for royal reds. What happened?

To try and find answers I reached out to a couple of my seafood contacts. Teresa and Bob Pitts are from the Perdido Key area and have been involved with commercial fishing most of their lives. Teresa currently manages Perdido Seafood and Bob works with the National Park Service but they both have strong ties to this industry. Jimbo Meador is a lifelong resident of Mobile Bay and has been involved in several industries including seafood over there. Jimbo recently retired from being nature tour operator in the Mobile Delta but still has ties to the seafood business and a wealth of knowledge. Dr. Andrew Ropicki is an economist with Florida Sea Grant and the University of Florida who focuses on seafood and other marine related topics. I had a conversation with all, and comments were made that helped connect some the dots.

In 1995 the state imposed a net ban on all entanglement nets 500 ft2 or larger from state waters. This obviously would have included Pensacola Bay. I know the shrimpers were opposed to this amendment. They were very visible and vocal about it. Once passed it would make sense they would move their operations from Pensacola Bay to Alabama, or federal waters offshore, so they could continue to use their standard sized otter trawls. Honestly, I do not remember which year the deck lights of the shrimp boats began to disappear, but I would guess many did leave when this law was passed. However, this did not impact the number of landings, they continued to bring shrimp here.

Otter trawl is correct name for what folks call a shrimp net. In 1995 any entanglement net over 500 square feet were banned in Florida waters.

Prior to 1995 landings of brown shrimp ranged from 1114 to 2523 a year with an average of 1760. Between 1995 and 2000 the range was from 1134 to 1816 with an average of 1442. A slight drop, but nothing significant. If they were shrimping somewhere else, they were still landing in Escambia County. I recently had a conversation about this with Bob Jackson, one of my citizen science volunteers. He moved here around 2000 and remembered shrimp boats still being on the bay at that time. Some may have moved due to the net ban, but not all. The shrimping was still on.

In 2002 the landings did take a significant drop – 835 landings that year. The first time they were below 1000/year since the records were kept in 1984. In 2003 they dropped further to 453 and the decline has continued ever since. Where were they landing their shrimp? Were they still shrimping? I do not know.

Jimbo asked the question “when did the surge of foreign imports begin?” Good question. We know now that at least 80% of the seafood consumed in Florida is imported. When did this move from local to import make this big swing? Dr. Ropicki found a world shrimp production graph that showed 2003 as a year with a big increase in aquaculture shrimp. Aquaculture accounted for 28% of global shrimp production in 2000 and 55% in 2010, and that is with wild caught shrimp increasing slightly. The big swing towards aquaculture in 2003 closely mirrors the decline in local wild harvest landings in 2002. This certainly could be a piece of the puzzle.

Seafood markets offer local products as well as those from around the world.

Photo: Florida Sea Grant

Did this competition with imports create less effort on the part of local shrimpers?

It certainly had some impact. All of my contacts indicated that the price difference between imported and local seafood made it much more difficult to do business. Add to this the rise in cost of fuel, insurance, and regulations to the industry, some captains did sell their boats and found another line of work.

Looking at the fuel story, Dr. Ropicki found a chart published by the U.S. Energy Information Administration. The chart shows how Gulf coast #2 diesel prices have changed since 1995. Basically from 1995 to 2021 they tripled (200% increase) while general inflation was only about a 75% increase. As many know it is a very fuel intensive industry.

In 2004 Hurricane Ivan hit our area and that certainly would have caused a decline in landings due to damage to boats and docks. The number of landings that year was 388. Between 2004 and 2010 landings steadily declined from 388 to 155/year. The days of 1000+ landings seemed to be over. Many shrimpers lost their boats during the storm and just found another line of work.

To add fuel to the fire, in 2010 the Deepwater Horizon oil spill occurred. That year there were only 85 landings in Escambia County, the first year we had less than 100. But we understand why – no shrimping occurred with oil in the water. Many shrimpers still in the business were hired to help clean up the spill, and did make money doing it, but they were not landing shrimp.

The BP Oil Spill was one of the worst natural disasters in our country’s history.

Photo: Gulf Sea Grant

In 2011 landings returned to 187 for the year and even up to 235 in 2012, but since there has been again a steady decline. In 2017 we went below 100 landings again. Between 2017 and 2019 the landings in Escambia County were 66, 53, and 70 respectively – the lowest ever. FAR below the 1000-2000 landings in the 1980s and 1990s.

Further discussion with my contacts yielded another trend. Commercial fishing historically was a family venture. Families worked the boats and sons took over the business from their fathers. That seems to have stopped. One shrimper who did talk to me said at one point we had between 40-50 boats in our fleet, now there are 11 and their kids want nothing to do with the business. As one of the contacts mentioned “they would rather work with their brains than their backs”.

In Alabama many families actually lived on their boats and the entire family would go out when the shrimping was on. I was told they do not see this anymore. There are still some bay shrimpers who sell their catch along the Hwy 90 causeway crossing Mobile Bay, and they seem to be doing well, but there are fewer of them. I was also told that many of the Gulf shrimp boats in Alabama have been sitting idle at dock for several years, many are up for sale, and it has been primarily foreign businesses buying them. There were once 120 Gulf shrimp boats in the fleet at Bon Secour Seafood, now there is one. I recently heard a Pensacola shrimper who made port in Bayou Chico – just sold his boat this year.

Dr. Ropicki also shared data on price for shrimp. Could this play a role in this story?

Most commercial seafood products have seen an increase in purchase price at the dock, but not shrimp. Checking the state records for price/pound for brown shrimp in Escambia County found some interesting trends. Between 1985 and 2020 the average price paid for their harvest was between $1.50 and $2.00 a pound. At least once each decade the price went to $2.00 or more per pound – but only ONCE each decade. In that time the number of years where the price dropped BELOW $1.50 per year steadily increased. Between 1985-89 the price dropped below $1.50 only once. Between 1990-1999 it never dropped below. Between 2000-2009 it dropped below $1.50/lb. six times. This happened again between 2010-2019 – six times. In 2006 local shrimpers only got $1.01/pound for the work – the lowest in this data set. If you look at the average price a shrimper received for their brown shrimp harvest by decade you see…

1985-89 – $1.82

1990-1999 – $1.78

2000-2009 – $1.58

2010-2019 – $1.54

A steady decline over time. Along with storms, regulations, fuel costs, lack of labor, and competition with imports, you can add price to the “soup of problems”.

I was curious if a similar scenario was playing out in Apalachicola. Apalach is known for their oysters, but there is a sizable shrimping industry there as well – it’s a seafood town. I asked our Sea Grant Agent over there, Erik Lovestrand, about similar trends. He did not have any data but was reasonably certain that the number of boats working out of their docks had significantly declined over the years.

I decided to take a look at the landing numbers for Apalachicola. I looked at brown shrimp.

Between 1985-1989 they averaged 909 landings – less effort for this species than in Escambia County.

Between 1990-1999 there averaged 1546 landings a year.

Between 2000-2009 the average was 382.

And between 2010-2020 it was 68.

The pattern looks similar albeit the number of landings was brown shrimp were less in Apalachicola. However, I did see another interesting difference – price paid per pound. In Escambia over this time the average price was $1.66/pound. It only went to $2.00/pound once decade and began to drop below $1.50 frequently over the last 20 years. However, in Apalachicola the average price was $2.00 rarely going below that and even reached $3.32/pound in 2014. They pay more for brown shrimp in Apalach. I am not sure if that impacted landings locally. The data suggests that it did not, but it is interesting.

And then, another thought came to mind. From the Big Bend of Florida south to Key West pink shrimp, not browns, are the target species. What did the pink shrimp landings look like? Did Escambia make a switch?

The results were interesting. Between 1985-2021 the landings of pink shrimp in Apalachicola occurred every year. The total number of landings was 6431 and averaged 174/year. The price was good, ranging from $1.80 to $3.23/pound, the average price was $2.39. The number of trips per year never broke 500 and the trend on landings shows a decline over this time period. But the price was decent for those who chose to target this shrimp.

In Escambia County the effort was low. They did not continuously land pink shrimp each year, but rather over short periods. Landings occurred between 1986-1991. Then nothing until 1997. Then another short period from 2000-2003. Then nothing again until 2014, which ran until 2020. Other than in 2000, the number of trips for pink shrimp were less than 10 a year (they were 10 in 2000). The average number of trips since 1986 was 4/year – less than Apalachicola and much less that the brown shrimp harvest here.

However, the price per pound was much higher for pink shrimp in Escambia. It ran from $1.59 to $5.00/pound! The average price was $2.77 (more than what they were paying in Apalachicola). Though Escambia landings were not big for pink shrimp, it was certainly more profitable than brown shrimp.

All of the above played play a role in the decline of the local shrimping industry. However, if you visit a local seafood market you will find shrimp. Some is still local, local landings may be down, but they have not stopped. Some are local in the since they were harvested elsewhere in the Gulf of Mexico and trucked to us. But as we mentioned, cheaper imports are easier to get. So, it does not seem we are going to run out of shrimp, just out of shrimpers. For some it is unnerving that we will be dependent on other countries for our seafood, but we will have seafood.

Which brings up the topic of aquaculture. This is for another article. Until then, we do encourage you to enjoy seafood, it is a healthy source of protein. We will see where the local industry heads in the next decade, but you can still get shrimp, and I have seen nice looking ones in there. Enjoy them.

Note: After completing this article I had a meeting in Bayou LaBatre AL. I was told that shrimping industry there was hanging on… barely. Also, the high school teacher I met with said he was not aware of one kid in the school who planned to become a shrimper… this is in Bayou LaBatre Alabama.

Special thanks to

Bob and Teresa Pitts – Perdido Bay Seafood

Jimbo Meador

Dr. Andrew Ropicki – University of Florida / Florida Sea Grant

Erik Lovestrand – UF IFAS Extension / Florida Sea Grant / Franklin County

Bob Jackson

![NISAW-logo09[1]](https://nwdistrict.ifas.ufl.edu/nat/files/2014/02/NISAW-logo091-300x119.jpg)