by Laura Tiu | Jun 3, 2017

There are five species of sea turtles that nest from May through October on Florida beaches. The loggerhead, the green turtle and the leatherback all nest regularly in the Panhandle, with the loggerhead being the most frequent visitor. Two other species, the hawksbill and Kemp’s Ridley nest infrequently. All five species are listed as either threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act.

Due to their threatened and endangered status, the Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission/Fish and Wildlife Research Institute monitors sea turtle nesting activity on an annual basis. They conduct surveys using a network of permit holders specially trained to collect this type of information. Managers then use the results to identify important nesting sites, provide enhanced protection and minimize the impacts of human activities.

Statewide, approximately 215 beaches are surveyed annually, representing about 825 miles. From 2011 to 2015, an average of 106,625 sea turtle nests (all species combined) were recorded annually on these monitored beaches. This is not a true reflection of all of the sea turtle nests each year in Florida, as it doesn’t cover every beach, but it gives a good indication of nesting trends and distribution of species.

If you want to see a sea turtle in the Florida Panhandle, please visit one of the state-permitted captive sea turtle facilities listed below, admission fees may be charged. Please call the number listed for more information.

If you want to see a sea turtle in the Florida Panhandle, please visit one of the state-permitted captive sea turtle facilities listed below, admission fees may be charged. Please call the number listed for more information.

- Gulf Specimen Marine Laboratory, 222 Clark Dr, Panacea, FL 32346 850-984-5297 Admission Fee

- Gulf World Marine Park, 15412 Front Beach Rd, Panama City, FL 32413 850-234-5271 Admission Fee

- Gulfarium Marine Adventure Park, 1010 Miracle Strip Parkway SE, Fort Walton Beach, FL 32548 850-243-9046 or 800-247-8575 Admission Fee

- Navarre Beach Sea Turtle Center, 8740 Gulf Blvd, Navarre, FL 32566 850-499-6774

To watch a female loggerhead turtle nest on the beach, please join a permitted public turtle watch. During sea turtle nesting season, The Emerald Coast CVB/Okaloosa County Tourist Development Council offers Nighttime Educational Beach Walks. The walks are part of an effort to protect the sea turtle populations along the Emerald Coast, increase ecotourism in the area and provide additional family-friendly activities. For more information or to sign up, please email ECTurtleWatch@gmail.com. An event page may also be found on the Emerald Coast CVB’s Facebook page: facebook.com/FloridasEmeraldCoast.

by Erik Lovestrand | May 22, 2016

Awareness is Growing!

Photo by: Aprile Clark

That is, when it comes to lights on our homes and businesses near their nesting beaches. Humans have long-known that artificial light can have negative consequences for many nocturnal animals, including nesting and hatching sea turtles. However, it has only been through fairly recent research that we are beginning to understand the reasons behind some of these effects and developing better lighting (or non-lighting) strategies and alternatives to protect our treasured marine turtle species.

Mother sea turtles that nest on Florida Panhandle beaches are “hard-wired” for nighttime activity when it comes to digging their nest cavities and depositing eggs. Likewise, their babies typically leave their sandy nests under cover of darkness, scampering to the Gulf of Mexico. This nocturnal behavior is important for avoiding predators that would have an easy meal of a baby turtle crossing the open beach in the light of day. However, even hatchlings emerging at night face a number of other obstacles. Once in the water there are a many aquatic predators that will not hesitate to gobble up a baby turtle. On average, it is estimated that only about 1 in 1000 babies survive to reach adulthood. With those odds, it would be wise for us to do anything we can to minimize additional threats or hazards during the short but crucial time these marine reptiles spend on the narrow thread of beachfront that we share with them.

One thing we can do involves reducing the disorienting effects of artificial light near our sea turtle nesting beaches. The term “phototactic” is used to describe organisms that are stimulated to move towards or away from light. Nesting females have been shown to avoid bright areas on the beach but hatchlings tend to be attracted to the brightest source of light when they emerge from the sand. On a nesting beach with no artificial lighting, any natural light from the moon or stars is reflected off the water, creating a much brighter horizon in that direction. This naturally attracts the hatchlings in the right direction. Lights from human sources can appear very bright in comparison and quite often draw babies over the dunes and into harm’s way on roadways, from predators, or simply by exposure once the sun comes up.

Many beachfront property owners have learned about this threat and have taken this issue to heart by reducing the amount of light on their property and eliminating or replacing lights visible from the nesting beach with sea turtle-friendly lighting. There are three rules to follow when retrofitting or installing new lighting near the beach.

- Keep it Long: Long-wave-length lighting that is still in the portion of the spectrum visible to humans includes amber, orange and red light. Manufacturers are now making highly efficient LED bulbs that are certified by the FWC as turtle-friendly.

- Keep it Low: Many times lighting needed for safety of access can be placed low enough to be unseen from the nesting beach.

- Keep it Shielded: Fixtures that are in line-of-site to the nesting beach need to be recessed to shield the bulb from being directly visible. The correct long-wave-length bulb should also be used in these shielded fixtures.

Remember, exterior lighting is not the only danger turtles face from our lights. Unobstructed interior lights seen through windows and doors can be just as detrimental. The best solution here is to tint beach-facing glass with a 15% transmittance tinting product. This will save money on cooling bills as well as protect interior furnishings and avoid the possibility that someone in your house might leave the blinds or curtains open accidentally during turtle season. If you have questions regarding turtle-safe lighting practices in Florida there are many resources available through the Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission the National Marine Fisheries Service, the Sea Turtle Conservancy, and your local UF/IFAS County Extension offices. If you really want to get into the nitty-gritty of turtle lighting and ways to protect turtles check out this FWC publication on assessing and resolving light pollution problems and this model lighting ordinance from UF’s Levin College of Law. Most Florida coastal counties have already adopted sea turtle lighting ordinances so you should also check your local county codes for this issue. Let’s help keep sea turtles in the dark, where they need to be.

by Laura Tiu | May 8, 2016

Florida has the highest number of sea turtles of any state in the continental US. Three species are common here including loggerhead, green and leatherback turtles. The Federal Endangered Species Act lists all of sea turtles in Florida as either threatened or endangered.

Sea turtle nesting season for the area began May 1, 2016. Adult females only nest every 2-3 years. At 20-35 years old, adult loggerhead and green female turtles return to the beach of their birth to nest. At this age, they are about 3 feet long and 250-300 pounds. The turtles will lay their eggs from May – September, with 50-150 baby turtles hatching after 45-60 days, usually at night. One female may nest several times in one season.

If you happen to see a sea turtle nesting, or nest hatching, stay very quiet, keep your distance, and turn any lights off (no flash photography). You should never try to touch a wild sea turtle. Also, do not touch or move any hatchlings. The small turtles need to crawl on the beach in order to imprint their birth beach on their memory.

During nesting season, it is important to keep the beaches Clean, Dark and Flat. Clean, by removing everything you brought to the beach including trash, food, chairs and toys; dark, by keeping lights off, using sea turtle friendly lighting and red LED flashlights if necessary; and flat, filling up all holes and knocking down sand castles before leaving the beach. If you see anyone harassing a sea turtle or a sea turtle in distress for any reason, do not hesitate to call the Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission hotline at 1-888-404-3922.

There has been encouraging sea turtle news in Florida as a result of the conservation actions being undertaken. There is an increasing number of green turtle nests and a decreasing number of dead turtles found on beaches.

If you want to see a sea turtle and learn more about these fascinating creatures, visit the Navarre Beach Sea Turtle Conservation Center, Navarre, FL, the Gulfarium Marine Adventure Park on Okaloosa Island, Fort Walton Beach, FL, or Gulf World Marine Park in Panama City, FL.

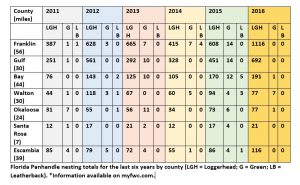

| County |

Beach nesting area (miles) |

Number of loggerhead sea turtle nests |

Number of green sea turtle nests |

Number of leatherback sea turtle nests |

| Franklin |

56 |

608 |

14 |

0 |

| Gulf |

29 |

451 |

14 |

0 |

| Bay |

44 |

170 |

12 |

5 |

| Walton |

30 |

94 |

4 |

3 |

| Okaloosa |

24 |

73 |

6 |

0 |

| Santa Rosa |

7 |

17 |

4 |

0 |

| Escambia |

39 |

86 |

4 |

1 |

Table 1: Data from the 2015 Florida Statewide Nesting Beach Survey available at: www.myfwc.com.

Young loggerhead sea turtle heading for the Gulf of Mexico. Photo: Molly O’Connor

The Foundation for the Gator Nation, An Equal Opportunity Institution.

by Rick O'Connor | May 8, 2016

When doing programs about snakes I find plenty of people who hate them… but I have never found anyone who hated turtles. I mean what is there to hate? They are slower, none of them are venomous, they have shoulders… people just like them. And to that point, when people see them crossing the road almost everyone wants to help. But that can be dangerous – for you and for the turtle. Here are couple of safety tips you should know before helping a turtle cross the road.

This small turtle can be held safely by grabbing it near the bridge area on each side.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

Your Safety

You would be surprised by the number of people, particularly children, that are hit by cars while trying to help turtles cross the road. One story I heard involved nine-year-old girl who was riding in the backseat with her grandmother. They both saw the turtle trying to cross a busy highway and wanted to help. The grandmother pulled over to the side but before she could even get the car in park the little girl opened the door and ran into the highway only to be struck by an oncoming car. We all like turtles, and do not want to see them hit by cars, but as sad as it is to see a turtle hit – it is horrific to see the same happen to a child. No matter what your age – please watch for traffic before attempting to help a turtle.

Turtles Bite

Yep… unlike their reptilian cousins the snakes, lizards, and alligator, turtles do not have teeth… but they do have a beak. The beak is made of a hard bony like material that is blade sharp in carnivorous turtles, and serrated like a saw in herbivorous ones – both can do serious damage. Some species of turtles feed on a variety of shellfish, and if they can crush shell they can certainly do a number on your hand – so you have to be careful. First thing you should do is determine whether the turtle needs to be handled. If traffic is not too bad, or the road not too wide, you may be able to just manage traffic so the turtle can cross on its own. If you feel that you must handle the turtle, there are safe ways to hold them. Smaller turtles can be held safely from the sides by grabbing the bridge area – the portion of the shell connecting the top (carapace) to the bottom (plastron). Many turtles will begin to kick their feet when you do this and their claws may scratch – be prepared for this. There are two groups of turtles that have extended necks and your hands, grasped near the bridge of their shell, are still within range of their mouths – these are the snapping and softshell turtles. Both are notorious for their bites. So how do you handle those? Below is a short video put together by the Toronto Zoo that gives you some ideas on how to handle those situations.

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=Lgd_B6iKPxU

Turtle Direction

Turtles cross highways for a variety of reasons – females looking for high dry ground to nest, individuals looking for more productive ponds, males looking for females – whatever the reason they are heading that way and will continue to do so. Placing them on the side of the highway where they came from will only initiate another attempt to cross. Move them to the side of the road they were heading.

The majority of turtle crossings occur during spring and summer. Untold numbers are killed each year on our highways – many gravid females carrying the next generation of the species. Though we encourage turtle conservation in Florida you do have to be smart about it. If you have any questions about Panhandle turtles in Florida contact your local extension office.

by Rick O'Connor | Apr 22, 2016

Many folks are putting together a “bucket list” of things they would like to do or see before they can no longer do them. For many interested in natural resources there are certain national parks and scenic places they would like to visit. Other natural resource fans have a list of wildlife species they would like to see.

Terrapins inhabit creeks, such as this one, within the expanse of the salt marsh. Here you can see their heads pop up above the water and you may get lucky enough to find one basking.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Recently I hooked with famed Alabama outdoorsman Jimbo Meador to search for locations to find Alabama turtles. Jimbo has been fishing, hunting, and enjoying the Mobile Bay area all of his life and he now using that knowledge as a guide in a nature-based tourism project. He recently received a call from a group of gentleman from another part of the country who had on their bucket list viewing 1000 reptilian species in their native habitat. In Alabama they were interested in the Black-knobbed Map Turtle, the Alabama Red Belly, and the Diamondback Terrapin. Jimbo has just begun the first module of the Florida Master Naturalist Program and reached out to us for advice on where to find these guys. Luckily, after working with scientists from the University of Alabama at Birmingham, I knew where to find diamondback terrapins – and have a pretty good idea on the others.

These “diamonds of the marsh” – as they are sometimes called – are very elusive creatures. They inhabit muddy bottom creeks within extensive salt marsh habitat all along the Gulf and East coast of the United States. I spent two years searching the Florida panhandle before I found my first live animal. It was one of the odd things though – once you have seen one, you now know what you are looking for and begin to find more.

I took Jimbo to a location near Dauphin Island where about 150 terrapins are believed to exist. Terrapins spend most of their day within creeks that meander through acres of salt marsh. The odd thing is there may be hundreds of creeks within these marshes and the terrapins – for some reason – will select their favorites and hang there. You can spend all day paddling through perfect looking creeks not seeing a head at all… then all of sudden… you enter one creek… not really any different than the others… and there they are.

Veteran waterman and outdoor guide, Jimbo Meador, explores the marshes near Dauphin Island for the elusive diamondback terrapin.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Within these creeks they feed on a variety of shellfish but particularly like the marsh periwinkles. These small snails are the ones that climb the cordgrass and needlerush plants during high tide to avoid their nemesis the blue crab and the diamondback terrapin. Terrapins do crawl out of the water to bask in the sun and have been known to bury in the loose fine mud. Females must find high dry ground to lay her eggs. She may swim as far as 5 miles from her home creek to find a suitable beach. They do like sandy beaches that are open and free of most plants. They emerge onto these beaches during May and June to lay about 7-10 eggs. Most females will lay more than one clutch each season emerging once every 16 days or so. Different from sea turtles – terrapins nest during the daylight hours. Actually the sunnier – the better. Raccoons are a big problem… find and consuming the eggs; on some beaches researchers have reported 90% or more of the nest have been raided by the furry guys. Crows, snakes, and possibly armadillos will take nests as well. If the developing young survive the 60+ days of incubation, they will emerge and head for the grass areas of the marsh… not the water. Here they will spend the first year of their life living more like a land turtle before they make their way to the brackish waters of the salt marsh.

Open sandy beaches, such as the one in this photograph, are the spots females terrapins seek when they are ready to dig a nest.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

These are fascinating creatures and should be on everyone’s natural resource bucket list. The hard effort of finding them really makes doing so very rewarding. On this day Jimbo saw only one head – I did not see any. I have found in my study site that I see more heads in the afternoon (we were out in the morning). I do not know if this is the case at all terrapin nesting sites, but something to consider when looking. Though we did not find many that day he now knows what to look for when searching for them. Next we will have to hunt the Alabama Red Belly Turtle. That is another story for another day.

We will continue this series with other interesting wildlife creatures to “hunt” in the Florida panhandle.

by Rick O'Connor | Apr 8, 2016

This gopher tortoise was found in the dune fields on a barrier island – an area where they were once found.

Photo: DJ Zemenick

The state of Florida has designated Sunday April 10 as “Gopher Tortoise Day”. The objective is to bring awareness to this declining species and, hopefully, an interest in protecting it.

During his travels across the southeast in the late 18th century, William Bartram mentioned this creature several times. As he walked through miles of open longleaf pine he would climb sand hills where he often encountered the tortoise. These turtles do like high dry sandy habitats. Here they dig their famous burrows into the earth.

These burrows can extend almost 10 feet vertically below the surface but, being excavated at an angle, can extend 20 feet in length. There is only one entrance and the tortoise works hard to maintain it. Field biologists have been able to identify over 370 species of upland creatures that utilize these burrows as refuge either for short or long periods of time. These include the declining diamondback rattlesnakes, gopher frogs, and the endangered indigo snakes, but most are insects and small mammals. Because of the importance of the burrows to these species, gopher tortoises are listed as keystone species – meaning their decline will trigger the decline of the others and can upset the balance of the ecosystem. Gopher burrows can be distinguished from mammal burrows in that they are domed across the top but flat along the bottom, as opposed to being oval. The width of the burrow is close to the length of the tortoise. When danger is encountered the tortoise will turn sideways – effectively blocking the entire entrance. Though there are cases of multiple tortoises in one, the general rule is one tortoise per burrow.

Tortoises are herbivores, feeding on a variety of young herbaceous shoots, and fruit when they can get find them. Fire is important to the longleaf system and it is important to the gophers as well. Fires encourage new young shoots to sprout. If an area does not receive sufficient fire, and the ground vegetation allowed grow larger with tougher leaves, the tortoise will abandon their burrow and seek more suitable habitat – which, especially in Florida – is becoming harder and harder to find. They typically breed in the fall and will lay their 5-10 eggs in the loose sand near the entrance of the burrow in spring. In August the hatchlings emerge and may hide beneath leaf litter, but will quickly begin their own burrows.

This tortoise is only found in the southeast of the United States and it is in decline across the region. They are currently listed as threatened in Florida but are federally protected in Louisiana, Mississippi, and western Alabama. They are found across our state as far south as the Everglades. There are several reasons why their numbers have declined. Human consumption was common in the early parts of the 20th century, and still is in some locations – though illegal. Some would, at times, pour gasoline down the burrow to capture rattlesnakes – this of course did not fare well for the tortoise. A big problem is the loss of suitable habitat. Much of upland systems require periodic fires to maintain the reproductive cycle of community members. The suppression of fire has caused the decline of many species in our state including gopher tortoises. These under maintained forest have forced tortoises to roadsides, power line fields, airports, and pastures. In each case they have encountered humans with cars, lawn mowers, and heavy equipment. Keep in mind also that our growing population is forcing us to clear much of these upland habitats for developments where clearing has caused the burial (entombment) of many burrows.

This is a unique turtle to our region and honestly, is a pleasure to see. We hope you will take the time to learn more about them by visiting FWC’s Gopher Tortoise Day website, enjoy watching them if they live near you, and help us conserve this species for future generations.

If you want to see a sea turtle in the Florida Panhandle, please visit one of the state-permitted captive sea turtle facilities listed below, admission fees may be charged. Please call the number listed for more information.

If you want to see a sea turtle in the Florida Panhandle, please visit one of the state-permitted captive sea turtle facilities listed below, admission fees may be charged. Please call the number listed for more information.