by Andrea Albertin | Jan 31, 2020

Contact you local county health department office for information on how to test your well water. Image: F. Alvarado Arce

Residents that rely on private wells for home consumption are responsible for ensuring the safety of their own drinking water. The Florida Department of Health (FDOH) recommends private well users test their water once a year for bacteria and nitrate.

Unlike private wells, public water supply systems in Florida are tested regularly to ensure that they are meeting safe drinking water standards.

Where can you have your well water tested?

Your best source of information on how to have your water tested is your local county health department. Most health departments test drinking water and they will let you know exactly what samples need to taken and ho w to submit a sample. You can also submit samples to a certified private lab near you.

Contact information for county health departments can be located at: http://www.floridahealth.gov/programs-and-services/county-health-departments/find-a-county-health-department/index.html

Contact information for private certified laboratories are found at https://fldeploc.dep.state.fl.us/aams/loc_search.asp

Why is it important to test for bacteria?

Labs commonly test for both total coliform bacteria and fecal coliforms (or E. coli specifically). This usually costs about $25 to $30, but can vary depending on where you have your sample analyzed.

- Coliform bacteria are a large, diverse group of bacteria and most species are harmless. But, a positive test for total coliforms shows that bacteria are getting into your well water. They are used as indicators – if coliform bacteria are present, other pathogens that cause diseases may also be getting into your well water. It is easier and cheaper to test for total coliforms than to test for a suite of bacteria and other organisms that can cause health problems.

- Fecal coliform bacteria are a subgroup of coliform bacteria found in human and other warm-blooded animal feces, in food and in the environment. E. coli are one group of fecal coliform bacteria. Most strains of E. coli are harmless, but some strains can cause diarrhea, urinary tract infections, and respiratory illnesses among others.

To ensure safe drinking water, FDOH strongly recommends disinfecting your well if the water tests positive for (1) only total coliform bacteria, or (2) both total coliform and fecal coliform bacteria (or E. coli). Disinfection is usually done through shock chlorination. You can either hire a well operator in your area to disinfect your well or you can do it yourself. Information for how to shock chlorinate your well can be found at http://www.floridahealth.gov/environmental-health/private-well-testing/_documents/well-water-facts-disinfection.pdf

Why is it important to test for nitrate concentration?

High levels of nitrate in drinking water can be dangerous to infants, and can cause “blue baby syndrome” or methemoglobinemia. This is where nitrate interferes with the blood’s capacity to carry oxygen. The Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL) allowed for nitrate in drinking water is 10 milligrams nitrate per liter of water (mg/L). It is particularly important to test for nitrate if you have a young infant in the home that is drinking well water or when well water is used to make formula to feed the infant.

If test results come back above 10 mg/L nitrate, use water from a tested source (bottled water or water from a public supply) until the problem is addressed. Nitrates in well water can come from fertilizers applied on land surfaces, animal waste and/or human sewage, such as from a septic tank. Have your well inspected by a professional to identify why elevated nitrate levels are in your well water. You can also consider installing a water treatment system, such as reverse osmosis or distillation units to treat the contaminated water. Before having a system installed, contact your local health department for more information.

In addition to once a year, you should also have your well water tested when:

- The color, taste or odor of your well water changes or if you suspect that someone became sick after drinking well water.

- A new well is drilled or if you have had maintenance done on your existing well

- A flood occurred and your well and/or septic tank were affected

Remember: Bacteria and nitrate are not the only parameters that well water is tested for. Call your local health department to discuss your what they recommend you should get the water tested for, because it can vary depending on where you live.

FDOH maintains an excellent website with many resources for private well users at http://www.floridahealth.gov/environmental-health/private-well-testing/index.html, which includes information on potential contaminants and how to maintain your well to ensure the quality of your well water.

by Shep Eubanks | Sep 13, 2019

Common Salvinia Covering Farm pond in Gadsden County

Photo Credit – Shep Eubanks UF/IFAS Gadsden County Extension

Close up of common Salvinia

Photo Credit – Shep Eubanks UF/IFAS Gadsden County Extension

Aquatic weed problems are common in the panhandle of Florida. Common Salvinia (Salvinia minima) is a persistent invasive weed problem found in many ponds in Gadsden County. There are ten species of salvinia in the tropical Americas but none are native to Florida. They are actually floating ferns that measure about 3/4 inch in length. Typically it is found in still waters that contain high organic matter. It can be found free-floating or in the mud. The leaves are round to somewhat broadly elliptic, (0.4–1 in long), with the upper surface having 4-pronged hairs and the lower surface is hairy. It commonly occurs in freshwater ponds and swamps from the peninsula to the central panhandle of Florida.

Reproduction is by spores, or fragmentation of plants, and it can proliferate rapidly allowing it to be an aggressive invasive species. When these colonies cover the surface of a pond as pictured above they need to be controlled as the risk of oxygen depletion and fish kill is a possibility. If the pond is heavily infested with weeds, it may be possible (depending on the herbicide chosen) to treat the pond in sections and let each section decompose for about two weeks before treating another section. Aeration, particularly at night, for several days after treatment may help control the oxygen depletion.

Control measures include raking or seining, but remember that fragmentation propagates the plant. Grass carp will consume salvinia but are usually not effective for total control. Chemical control measures include :carfentrazone, diquat, fluridone, flumioxazin, glyphosate, imazamox, and penoxsulam.

For more information reference these IFAS publications:

Efficacy of Herbicide Active ingredients Against Aquatic Weeds

Common salvinia

For help with controlling Common salvinia consult with your local Extension Agent for weed control recommendations, as needed.

by Laura Tiu | Aug 9, 2019

During a recent fishing trip, as we jigged for bait and got repeated stuck by the tiny hooks, talk turned to the recent reports of a death and infections in the Florida Panhandle from the saltwater-dwelling bacterium, Vibrio vulnificus. Many reports used the term “flesh-eating bacteria” to refer to Vibrio. This description is false and misleading and causes unnecessary fear and panic. Most healthy individuals are not at risk for V. vulnificus infection, however, to ensure that your time on the water is safe and enjoyable, be aware of your risk and take steps to minimize becoming infected.

The name Vibrio refers to a large and diverse group of marine bacteria. Most members are harmless, however, some strains produce harmful toxins and are capable of causing a disease known as “vibriosis.” Because of Florida’s warm climate, Vibrio are present in brackish waters year-round. They are most abundant from April to November when the water is the warmest. For infection to occur, pathogenic Vibrio strains must enter the body of a susceptible individual who either eats raw and contaminated seafood or exposes an open wound for a prolonged period in water containing these bacteria.

Symptoms of vibriosis may arise within 1–3 days, but usually occur a few hours after exposure. Infections typically begin with swelling and redness of skin, followed by severe pain, blistering, and discharge at the site of the wound. If you suspect infection, seek medical treatment immediately.

Anglers can reduce their risk by following a few safety tips. Because fish, including live bait, carry Vibrio on their bodies, avoid or minimize handling whenever possible. The proper use of landing gear and release tools can help to minimize handling. If you cannot avoid handling the fish, use a wet towel or gloves to protect yourself. Be aware of areas that can cause injury like spines, barbs, and teeth.

Always wash your hands thoroughly after fishing, especially before handling food. Be sure to clean your gear after each use, taking special care with sharp objects like hooks and knives.

Adapted from: Abeels, H., G. Barbarite, A. Wright, and P. McCarthy. 2016. Frequently Asked Questions about Vibrio in Florida. SGEF-231. https://eos.ucs.uri.edu/EOS_Linked_Documents/flsgp/SGEF_231_fact-sheet_2016.pdf

“An Equal Opportunity Institution”

A happy angler with a Trigger fish near Destin, Florida (Photo credit: L. Tiu).

by Andrea Albertin | May 3, 2019

The major goal of the Wakulla Springs Basin Management Action Plan (BMAP) is to reduce nitrogen loads to Wakulla Springs. Septic systems are identified as the primary source of this nitrogen. Photo: A. Albertin

A Basin Management Action Plan, or BMAP, is a management plan developed for a waterbody (like a spring, river, lake, or estuary) that does not meet the water quality standards set by the state. One or more pollutants can impair a waterbody. In Florida, the most common pollutants are nutrients (particularly nitrate), pathogens (fecal coliform bacteria) and mercury.

The goal of the BMAP is to reduce the pollutant load to meet water quality standards set by the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP). BMAPS are roadmaps with a list of projects and management action items to reach these standards. FDEP develops them with stakeholder input. Targets are set at 20 years, and progress towards those targets is assessed every five years.

It’s important to understand that a BMAP encompasses the entire land area that contributes water to a given waterbody. For example, the land area that contributes water to Jackson Blue Springs and Merritts Mill Pond (either from surface waters or groundwater flow) is 154 square miles, while the Wakulla Springs Basin covers an area of 1,325 square miles.

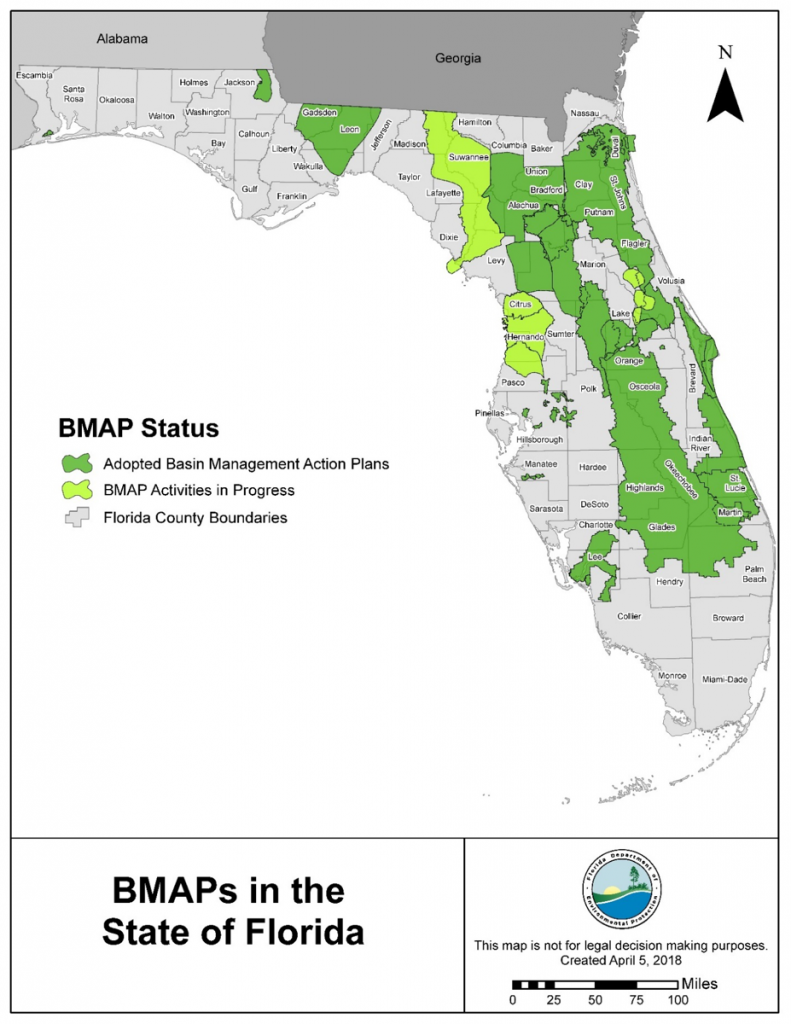

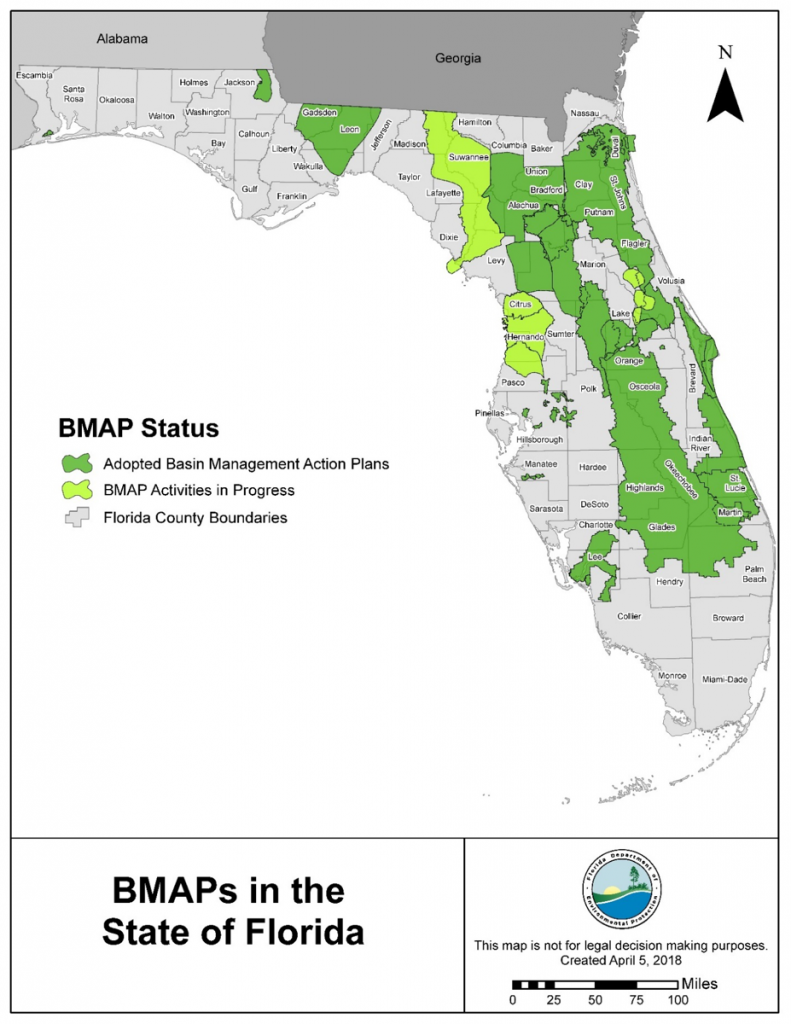

BMAPs in the Panhandle

There are 33 adopted BMAPS in the state, and 5 that are pending adoption. Here in the Panhandle, we have three adopted BMAPS. They are the Bayou Chico BMAP in Escambia County, the Wakulla Springs BMAP in Wakulla, Leon, Gadsden and small parts of Jefferson County, and the Jackson Blue/Merritts Mill Pond BMAP in Jackson County. All three are impaired for different reasons.

- Bayou Chico discharges into Pensacola Bay and is polluted by fecal coliform bacteria. The BMAP addresses ways to reduce coliforms from humans and pets, which includes sewer expansion projects, stormwater runoff management, septic tank inspections, pet waste ordinances and a Clean Marina and Boatyard program.

- Wakulla Springs Nitrate from human waste is the main pollutant to Wakulla Springs, and Tallahassee’s wastewater treatment facility and the city’s Southeast Sprayfield were identified as the main sources. Both sites were upgraded (the sprayfield was moved), greatly reducing nitrate contributions to the spring basin. The BMAP is focused on septic systems and septic to sewer hookups.

- Jackson Blue/Merritts Mill Pond Nitrate is also the primary pollutant to the Jackson Blue/Merritts Mill Pond Basin, but nitrogen fertilizer from agriculture is identified as the main source. This BMAP focuses on farmers implementing Best Management Practices (BMPs), land acquisition by the Northwest Florida Water Management District , as well as septic tanks, recognizing their nitrogen contribution to Merritts Mill Pond.

Once all the BMAPS are adopted, FDEP states that almost 14 million acres will be under active basin management, an area that includes more than 6.5 million Floridians.

Adopted and pending BMAPS in Florida. Source: FDEP Statewide Annual Report, June 2018

How are residents living in an area with a BMAP affected? It varies by BMAP and specifically land use within its boundaries. For example, in BMAPs where nitrogen from septic systems are found to be a major source of nutrient impairment to a water body, septic to sewer hookups, or septic system upgrades to more advanced treatment units will be required in specific areas. In urban areas where nitrogen fertilizer is an important source, municipalities are required to adopt fertilizer ordinances. Where nitrogen fertilizer from agricultural production is a major source of impairment, producers are required to implement Best Management Practices to reduce nitrogen loads.

More information about BMAPS

For specific information on BMAPS, FDEP has an excellent website: https://floridadep.gov/dear/water-quality-restoration/content/basin-management-action-plans-bmaps All BMAPs (full reports with specific action items listed) can be found there, along with maps, information about upcoming meetings and webinars and other pertinent information.

Your local Health Department Office is the best resource regarding septic systems and any ordinances that may apply to you depending on where you live. Your Water Management District (in the Panhandle it’s the Northwest Florida Water Management District) is also an excellent resource and staff can let you know whether or not you live or farm in an area with a BMAP and how that may affect you.

by Andrea Albertin | Mar 20, 2019

By Vance Crain and Andrea Albertin

Fisherman with a large Shoal Bass in the Apalachicola-Chattahootchee-Flint River Basin. Photo credit: S. Sammons

Along the Chipola River in Florida’s Panhandle, farmers are doing their part to protect critical Shoal Bass habitat by implementing agricultural Best Management Practices (BMPs) that reduce sediment and nutrient runoff, and help conserve water.

Florida’s Shoal Bass

Lurking in the clear spring-fed Chipola River among limerock shoals and eel grass, is a predatory powerhouse, perfectly camouflaged in green and olive with tiger stripes along its body. The Shoal Bass (a species of Black Bass) tips the scale at just under 6 lbs. But what it lacks in size, it makes up for in power. Unlike any other bass, and found nowhere else in Florida, anglers travel long distances for a chance to pursue it. Floating along the swift current, rocks, and shoals will make you feel like you’ve been transported hundreds of miles away to the Georgia Piedmont, and it’s only the Live Oaks and palms overhanging the river that remind you that you’re still in Florida, and in a truly unique place.

Native to only one river basin in the world, the Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint (ACF) River Basin, habitat loss is putting this species at risk. The Shoal Bass is a fluvial specialist, which means it can only survive in flowing water. Dams and reservoirs have eliminated habitat and isolated populations. Sediment runoff into waterways smothers habitat and prevents the species from reproducing.

In the Chipola River, the population is stable but its range is limited. Some of the most robust Shoal Bass numbers are found in a 6.5-mile section between the Peacock Bridge and Johnny Boy boat ramp. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission has turned this section into a Shoal Bass catch and release only zone to protect the population. However, impacts from agricultural production and ranching, like erosion and nutrient runoff can degrade the habitat needed for the Shoal Bass to spawn.

Preferred Shoal Bass habitat, a shoal in the Chipola River. Photo credit: V. Crain

Shoal Bass habitat conservation and BMPs

In 2010, the Southeast Aquatic Resources Partnership (SARP), the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation and a group of scientists (the Black Bass Committee) developed the Native Black Bass Initiative. The goal of the initiative is to increase research and the protection of three Black Bass species native to the Southeast, including the Shoal Bass. It also defined the Shoal Bass as a keystone species, meaning protection of this apex predators’ habitat benefits a host of other threatened and endangered species.

Along the Chipola River, farmers are teaming up with SARP and other partners to protect Shoal Bass habitat and improve farming operations through BMP implementation. A major goal is to protect the river’s riparian zones (the areas along the borders). When healthy, these areas act like sponges by absorbing nutrients and sediment runoff. Livestock often degrade riparian zones by trampling vegetation and destroying the streambank when they go down to a river to drink. Farmers are installing alternative water supplies, like water wells and troughs in fields, and fencing out cattle from waterways to protect these buffer areas and improve water quality. Row crop farmers are helping conserve water in the river basin by using advanced irrigation technologies like soil moisture sensors to better inform irrigation scheduling and variable rate irrigation to increase irrigation efficiency. Cost-share funding from SARP, the USDA-NRCS and FDACS provide resources and technical expertise for farmers to implement these BMPs.

Holstein drinking from a water trough in the field, instead of going down to the river to get water which can cause erosion and problems with water quality. Photo credit: V. Crain

By working together in the Chipola River Basin, farmers, fisheries scientists and resource managers are helping ensure that critical habitat for Shoal Bass remains healthy. Not only is this important for the species and resource, but it will ensure that future generations can continue to enjoy this unique river and seeing one of these fish. So the next time you catch a Shoal Bass, thank a farmer.

For more information about BMPs and cost-share opportunities available for farmers and ranchers, contact your local FDACS field technician: https://www.freshfromflorida.com/Divisions-Offices/Agricultural-Water-Policy/Organization-Staff and NRCS field office USDA-NRCS field office: https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/main/fl/contact/local/ For questions regarding the Native Black Bass Initiative or Shoal Bass habitat conservation, contact Vance Crain at vance@southeastaquatics.net

Vance Crain is the Native Black Bass Initiative Coordinator for the Southeast Aquatic Resource Partnership (SARP).

by Judy Biss | Nov 9, 2018

Farm ponds are used in a number of different ways, including fishing, irrigation, water control, and wildlife viewing. UF/IFAS Photo by Tyler Jones.

Farm ponds of all shapes and sizes are common in rural Northwest Florida. They are built for a number of reasons such as irrigation, water management, boating, fishing, wildlife viewing, livestock watering, and food production. Each of these uses guides the way the pond is managed to maintain its function, as well as its ecological beauty, but a factor that is important to all uses is having enough oxygen!

As you have probably observed, your pond is a dynamic system, which is influenced literally from the ground up! Much of the water’s basic chemical and physical characteristics reflect those of underlying soils (sand, clay, organic, etc.) and major sources of water (ground water, rainfall, runoff, etc.). The pond’s characteristics also influence how much oxygen is available for use by the plants and animals that live in it.

Why is Dissolved Oxygen and Aeration so Important?

Fish kills are often the result of low dissolved oxygen levels and occur in both natural waters and man-made ponds. Photo by Vic Ramey.

The idea of oxygen being dissolved in water is a little counter-intuitive. Especially to us, as air-breathing humans! Think of your pond as a giant living, breathing organism. Its atmosphere is the water itself, and it contains dissolved oxygen gas for the fish, aquatic plants, insects, and zooplankton to “breathe.” Even bacteria need to breathe, and one of their fundamental roles in your pond is the decomposition of organic wastes like un-eaten fish food, and dead plant and animal materials.

Having enough dissolved oxygen in the water is one of the driving forces sustaining the health of your pond. Oxygen is dissolved into water directly from the atmosphere, wind and wave action, and by plant photosynthesis. Because warm water “holds” less dissolved oxygen than cold water, your pond’s dissolved oxygen levels can be lower in the summer than in the winter, especially in the early morning hours before plants begin to photosynthesize and produce oxygen. While longer days and warmer temperatures mean more sunlight for plants to photosynthesize and produce oxygen, the demand or need for oxygen by fish, bacteria, and other aquatic organisms is also increased. Periods of rainy, overcast days during the summer can greatly reduce oxygen production by plant photosynthesis. Combined that with the increased oxygen demand by other organisms, and dissolved oxygen levels can drop fast. These drops in dissolved oxygen levels often result in fish kills. Productive, nutrient-rich ponds with high levels of organic materials, and a high fish density are at a greater risk of the devastating effects of low dissolved oxygen levels.

What Can You Do to Insure Your Pond Has Enough Oxygen?

Do not be tempted to overfeed your fish. Feed them floating fish food so you can see how much they will consume in 10 to 15 minutes at each feeding. Consider feeding them every other day. In addition, as recommended in Managing Florida Ponds for Fishing “do not feed them when the water temperature is below 60° F, or, above 95° F. Fish do not actively feed at these times.” Use fish feeding behavior as your guide. Uneaten food will only add excess organic matter to the pond. The decomposition of this excess organic matter by bacteria increases the oxygen demand and likewise increases the chances of low oxygen levels and a fish kill.

Reduce nutrient inputs from runoff, livestock waste, excess fertilizer, and uneaten foods as described above, to help reduce the demand for oxygen in the system. Additionally, remove as much excess debris as possible that may have been blown into your pond as a result of October’s Hurricane Michael that affected much of Florida’s panhandle. Excess nutrients from these sources are freely available for use by hungry algae and other plants, which can then proliferate and, in turn, cause demand for more oxygen. This increased demand for oxygen can cause fish kills due to low oxygen levels as described above.

If you have an aerator, keep it operative especially during extended periods of cloudy and rainy weather. Watch your fish for signs of oxygen stress (not eating, remaining near and gulping at the surface) and aerate accordingly. Oxygen levels naturally fluctuate, and the lowest levels occur in the late evening through early morning hours when plants are not photosynthesizing and replenishing oxygen. Therefore, most important time to routinely operate the aerator is the late overnight hours into early morning.

If you don’t have an aerator, consider purchasing one, especially as your pond ages and grows more fish, plants, and algae. It is certainly less costly in the end to be proactive when it comes to maintaining adequate dissolved oxygen in your pond.

Recreation and fishing are important uses of many rural farm ponds. Photo by UF/IFAS Tyler Jones.

What kind of Aerator should I get?

There are a few basic aerator types. There are surface water agitators or fountains, and there are bottom air diffusers. They can be powered by electricity, wind, or solar power.

Diffuser aerators can help achieve a uniform oxygen distribution in your pond from top to bottom. This is especially important in deeper ponds (greater than 6-10 feet average depth) where temperature and oxygen stratification can occur. Diffuser aerators pump surface air through the base sitting on the bottom of the pond causing bubbles of air to rise to the surface. Diffusers also increase circulation and keep the deeper parts of your pond from becoming oxygen depleted. In a new pond, or one with flocculent sediments, a diffuser may cause turbidity due to the physical action of the diffuser base sitting on the pond bottom circulating oxygen from the bottom to the surface.

Other aerator options are the fountain sprays or surface agitators that aerate surface water. At a bare minimum, this can be a hose shooting water out over the water surface. Surface fountains and agitators work well in small shallow ponds, but are generally not recommended for larger more productive ponds that need more oxygen. In some commercial or farm ponds, paddle wheel agitators powered by a tractor’s pto are used during periods of low oxygen as an emergency measure when a fish kill is just beginning to occur.

Where Can I Purchase One?

The type or types of aerators you need for your pond will depend on the pond’s size, depth, level of productivity (nutrient level, number of fish), use, and water quality. There are a number of shopping options online for pond aerators. Try searching using the term “pond aerators Florida.” Also, some local Panhandle fingerling fish farms sell these products too. Here is a list of fish farms from the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission: FWC Freshwater Fish Stocking List. Additionally, there are dissolved oxygen meters you can purchase which accurately read the amount of oxygen in your ponds. This is yet another tool to use in the overall management of your pond.

Simple surface agitators can be used to aerate small shallow ponds, but are generally not recommended for larger more productive ponds that need more oxygen. Photo by Judy Biss

More information about pond management can be found in the following references used for this article:

Overview of Florida Waters – Dissolved Oxygen

Clemson Cooperative Extension: Aeration, Circulation, and Fountains

Southern Regional Aquaculture Center: Pond Aeration

Managing Florida Ponds for Fishing

The Role of Aeration in Pond Management