by Andrea Albertin | Jan 28, 2021

Senate Bill 712 ‘The Clean Waterways Act’ was signed into Florida law on June 30, 2020. The purpose of the bill is to better protect Florida’s water resources and focuses on minimizing the impact of known sources of nutrient pollution. These sources include septic systems, wastewater treatment plants, stormwater runoff as well as fertilizer used in agricultural production.

Senate Bill 712 focuses on protecting Florida’s water resources such as Jackson Blue Springs/Merritt’s Mill Pond, pictured here. Credit: Doug Mayo, UF/IFAS.

What major provisions are included in SB 712?

Primary actions required by SB712 were listed in a news release by Governor Desantis’ staff in June 2020 as:

- Regulation of septic systems as a source of nutrients and transfer of oversight from the Florida Department of Health (DOH) to the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (DEP).

- Contingency plans for power outages to minimize discharges of untreated wastewater for all sewage disposal facilities.

- Provision of financial records from all sanitary sewage disposal facilities so that DEP can ensure funds are being allocated to infrastructure upgrades, repairs, and maintenance that prevent systems from falling into states of disrepair.

- Detailed documentation of fertilizer use by agricultural operations to ensure compliance with Best Management Practices (BMPs) and aid in evaluation of their effectiveness.

- Updated stormwater rules and design criteria to improve the performance of stormwater systems statewide to specifically address nutrients.

How does the bill impact septic system regulation?

The transfer of the Onsite Sewage Program (OSP) (commonly known as the septic system program) from DOH to DEP becomes effective on July 1, 2021. So far, DOH and DEP submitted a report to the Governor and Legislature at the end of 2020 with recommendations on how this transfer should take place. They recommend that county DOH employees working in the OSP continue implementing the program as DOH-employees, but that the onsite sewage program office in the State Health Office transfer to DEP and continue working from there. DOH created an OSP Transfer web page where updates and documents related to the transfer are posted.

How does the bill impact agricultural operations?

SB 712 affects all landowners and producers enrolled in the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services (FDACS) BMP Program. Under this bill:

- Every two years FDACS will make an onsite implementation verification (IV) visit to land enrolled in the BMP program to ensure that BMPs are properly implemented. These visits will be coordinated between the producer and field staff from FDACS Office of Agriculture and Water Policy (OAWP).

- During these visits (and as they have done in the past), field staff will review records that producers are required to keep under the BMP program.

- Field staff will also collect information on nitrogen and phosphorus application. FDACS has created a specific form, the Nutrient Application Record Keeping Form or NARF where producers will record quantities of N and P applied. FDACS field staff will retain a copy of the NARF during the IV visit.

FDACS-OAWP prepared a thorough document with responses to SB 712 Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ’s). It includes responses to questions about site visits, the NARF and record keeping, why FDACS is collecting nutrient records and what will be done with this information. The fertilizer records collected are not public information, and are protected under the public records exemption (Section 403.067 Florida Statutes). For areas that fall under a Basin Management Action Plan (like the Jackson Blue and Wakulla Springs Basins in the Florida Panhandle), FDACS will combine the nitrogen and phosphorus application data from all enrolled properties (total pounds of N and P applied within the BMAP). It will then send the aggregated nutrient application information to FDEP.

Details of how all aspects of SB 712 will be implemented are still being worked out and we should continue to hear more in the coming months.

by Andrea Albertin | Oct 9, 2020

Special care needs to be taken with your septic system after flooding. Image: B. White NASA. Public Domain

During and after floods or heavy rains, the soil in your septic system drainfield can become waterlogged. For your septic system to treat wastewater, water needs to drain freely in the drainfield. Special care needs to be taken with your septic system under flood conditions.

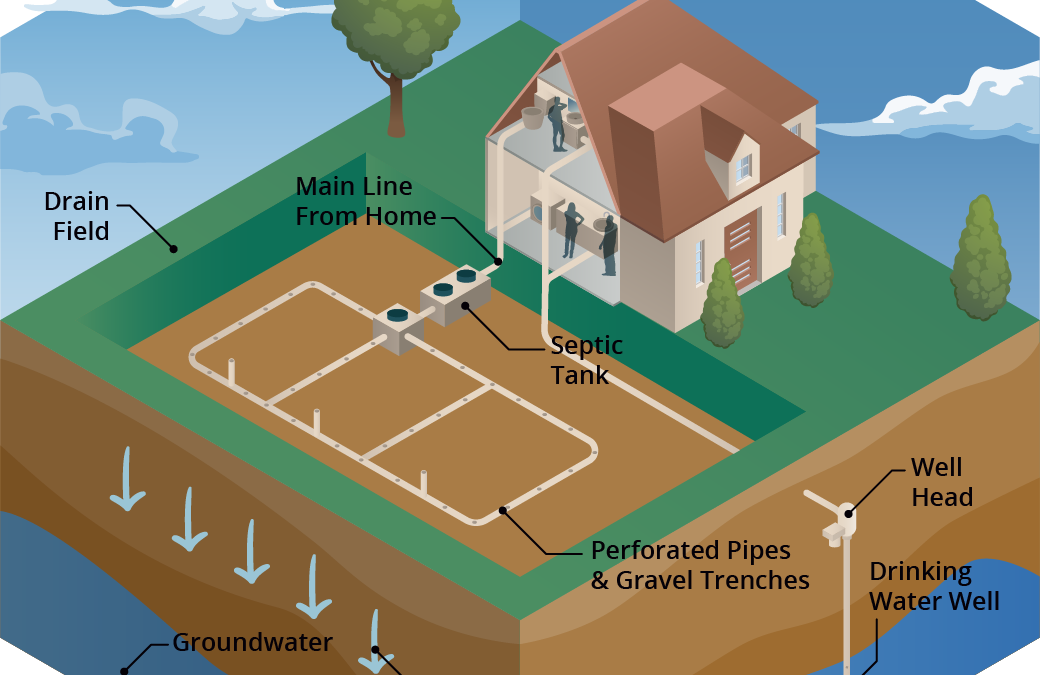

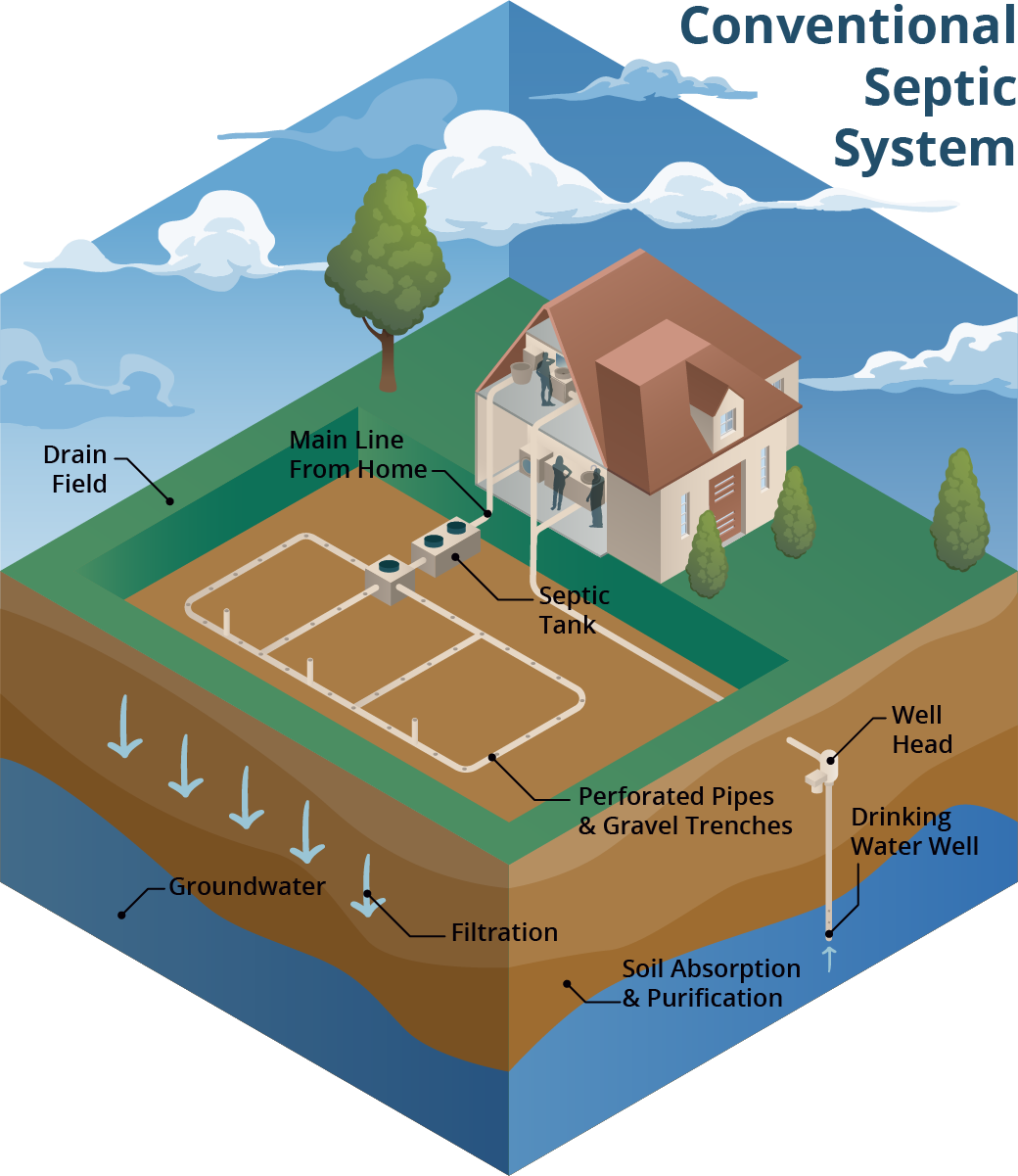

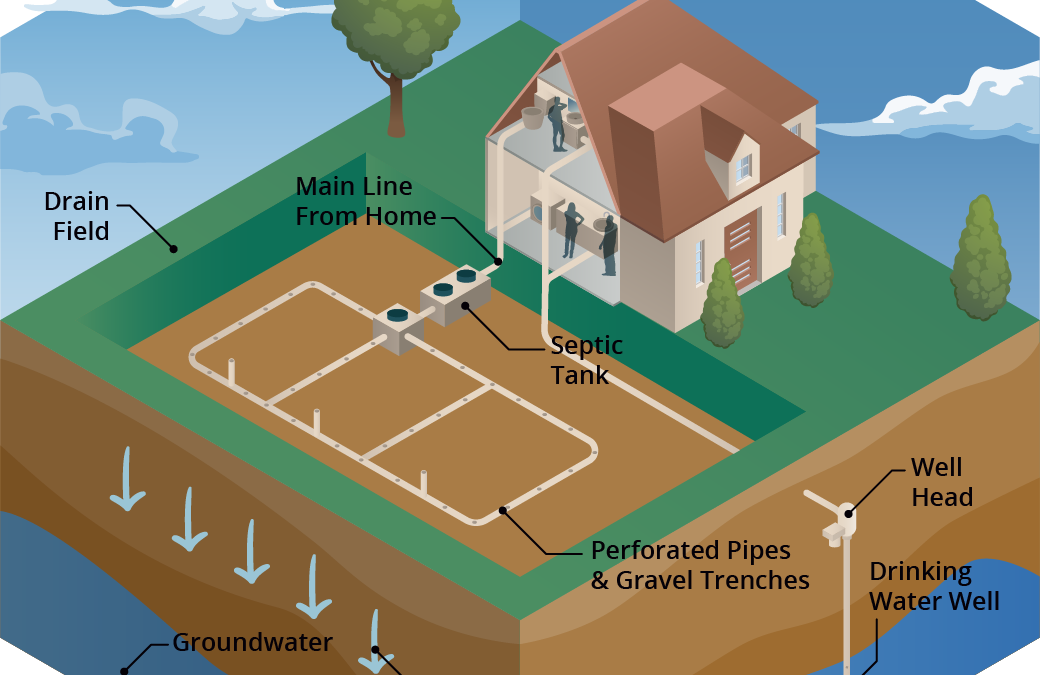

A conventional septic system is made up of a septic tank (a watertight container buried in the gound) and a drainfield. Image: Soil and Water Science Lab UF/IFAS GREC.

A conventional septic system is made up of a septic tank and a drainfield or leach field. Wastewater flows from the septic tank into the drainfield, which is typically made up of a distribution box (to ensure the wastewater is distributed evenly) and a series of trenches or a single bed with perforated PVC pipes. Wastewater seeps from these pipes into the surrounding soil. Most wastewater treatment occurs in the drainfield soil. When working properly, many contaminants, like harmful bacteria, are removed through die-off, filtering and interaction with soil surfaces.

What should you do if flooding occurs?

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) offers these guidelines:

- Relieve pressure on the septic system by using it less or not at all until floodwaters recede and the soil has drained. Under flooded conditions, wastewater can’t drain in the drainfield and can back up in your septic system and household drains. Clean up floodwater in the house without dumping it into the sinks or toilet. This adds additional water that an already saturated drainfield won’t be able to process. Remember that in most homes all water sent down the pipes goes into the septic system.

- Avoid digging around the septic tank and drainfield while the soil is waterlogged. Don’t drive vehicles or equipment over the drainfield. Saturated soil is very susceptible to compaction. By working on your septic system while the soil is still wet, you can compact the soil in your drainfield, and water won’t be able to drain properly. This reduces the drainfield’s ability to treat wastewater and leads to system failure.

- Don’t open or pump the septic tank if the soil is waterlogged. Silt and mud can get into the tank if it is opened and can end up in the drainfield, reducing its drainage capability. Pumping under these conditions can cause a tank to float or ‘pop out’ of the ground, and can damage inlet and outlet pipes.

- If you suspect your system has been damaged, have the tank inspected and serviced by a professional. How can you tell if your system is damaged? Signs include: settling, wastewater backs up into household drains, the soil in the drainfield remains soggy and never fully drains, a foul odor persists around the tank and drainfield.

- Keep rainwater drainage systems away from the septic drainfield. As a preventive measure, make sure that water from roof gutters doesn’t drain towards or into your septic drainfield. This adds an additional source of water that the drainfield has to process.

- Have your private well water tested if your septic system or well were flooded or damaged in any way. Your well water may not be safe to drink or use for household purposes (making ice, cooking, brushing teeth or bathing). You need to have it tested by the Health Department or other certified laboratory for total coliform bacteria and coli to ensure it is safe to use.

For more information on septic system maintenance after flooding, go to:

More information on having your well water tested can be found at:

More Information on conventional and advanced treatment septic systems can be found on the UF/IFAS Septic System website

by Andrea Albertin | Oct 2, 2020

If your private well was damaged or flooded due to hurricane or other heavy storm activity, your well water may not be safe to drink. Well water should not be used for drinking, cooking purposes, making ice, brushing teeth or bathing until it is tested by a certified laboratory for total coliform bacteria and E. coli.

Residents should use bottled, boiled or treated water until their well water has been tested and deemed safe.

- Boiling: To make water safe for drinking, cooking or washing, bring it to a rolling boil for at least one minute to kill organisms and then allow it to cool.

- Disinfecting with bleach: If boiling isn’t possible, add 1/8 of a teaspoon or about 8 drops of fresh unscented household bleach (4 to 6% active ingredient) per gallon of water. Stir well and let stand for 30 minutes. If the water is cloudy after 30 minutes, repeat the procedure once.

- Keep treated or boiled water in a closed container to prevent contamination

Use bottled water for mixing infant formula.

Where can you have your well water tested?

Contact your county health department for information on how to have your well water tested. Image: F. Alvarado Arce

Most county health departments accept water samples for testing. Contact your local department for information about what to have your water tested for (they may recommend more than just bacteria), and how to collect and submit the sample.

Contact information for Florida Health Departments can be found here: County Health Departments – Location Finder

You can also submit samples to a certified commercial lab near you. Contact information for commercial laboratories that are certified by the Florida Department of Health are found here: Laboratories certified by FDOH

This site includes county health department labs, commercial labs as well as university labs. You can search by county.

What should you do if your well water sample tests positive for bacteria?

The Florida Department of Health recommends well disinfection if water samples test positive for total coliform bacteria or for both total coliform and E. coli, a type of fecal coliform bacteria.

You can hire a local licensed well operator to disinfect your well, or if you feel comfortable, you can shock chlorinate the well yourself.

You can find information on how to shock chlorinate your well at:

After well disinfection, you need to have your well water re-tested to make sure it is safe to use. If it tests positive again for total coliform bacteria or both total coliform and E. coli call a licensed well operator to have the well inspected to get to the root of the problem.

Well pump and electrical system care

If the pump and/or electrical system have been underwater and are not designed to be used underwater, do not turn on the pump. There is a potential for electrical shock or damage to the well or pump. Stay away from the well pump while flooded to avoid electric shock.

Once the floodwaters have receded and the pump and electrical system have dried, a qualified electrician, well operator/driller or pump installer should check the wiring system and other well components.

Remember: You should have your well water tested at any time when:

- A flood occurred and your well was affected

- The color, taste or odor of your well water changes or if you suspect that someone became sick after drinking your well water.

- A new well is drilled or if you have had maintenance done on your existing well

- There has been any type of chemical spill (pesticides, fuel, etc.) into or near your well

The Florida Department of Health maintains an excellent website with many resources for private well users: FDOH Private Well Testing and other Reosurces which includes information on potential contaminants and how to maintain your well to ensure the quality of your well water.

by Andrea Albertin | Apr 9, 2020

Pitt Spring in the Florida Panhandle is one of more than 1,000 freshwater springs in the state. Springs serve as ‘windows’ to groundwater quality, since the water that flows from them comes largely from the Upper Floridan Aquifer. Photo: A. Albertin

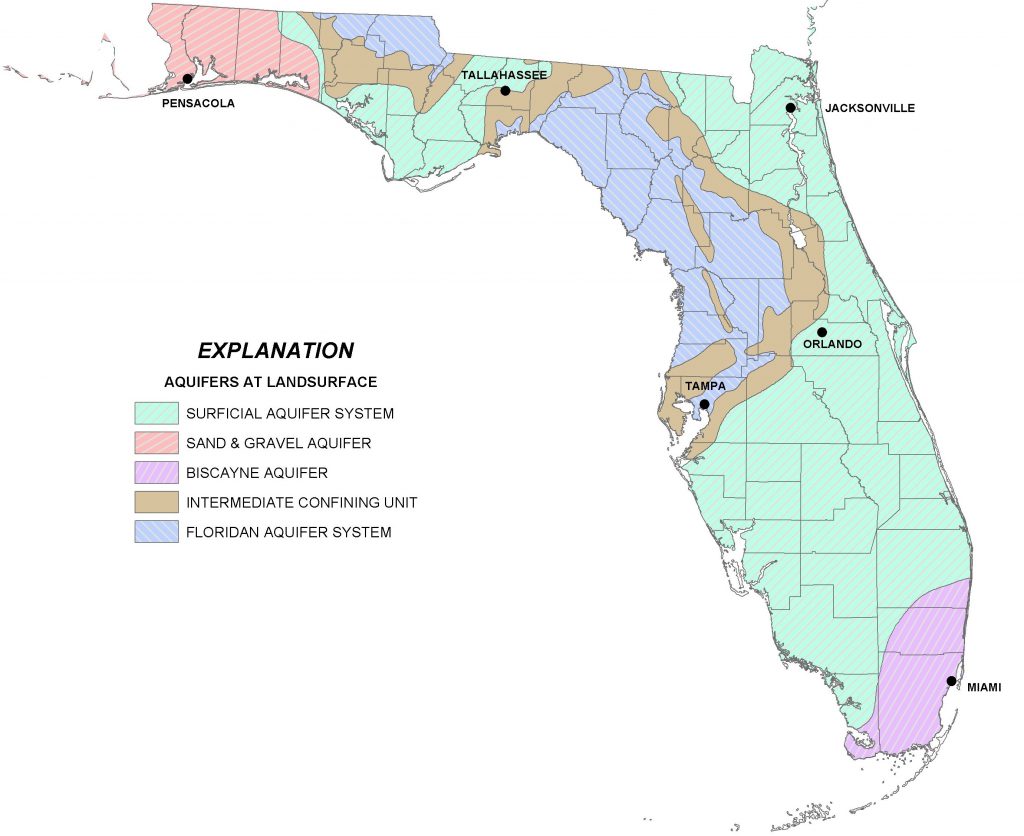

As Florida residents, we are so fortunate to have the Floridan Aquifer lying below us, one of the most productive aquifer systems in the world. The aquifer underlies an area of about 100,000 square miles that includes all of Florida and extends into parts of Alabama, Georgia and South Carolina, as well as parts of the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico (Figure 1). The Floridan Aquifer consists of the Upper and Lower Floridan Aquifer.

Figure 1. Map of the extent of the Floridan Aquifer. Areas in gray show where the aquifer is buried deep below the land surface, while areas in light brown indicate where the aquifer is at land surface. Many springs in Florida are found in these light brown areas. Source: USGS Publication HA 730-G.

Aquifers are immense underground zones of permeable rocks, rock fractures and unconsolidated (or loose) material, like sand, silt and clay that hold water and allow water to move through them. Both fresh and saltwater fill the pores, fissures and conduits of the Floridan Aquifer. Saltwater, which is more dense than freshwater, is found in all areas of the deeper aquifer below the freshwater.

The thickness of the Floridan Aquifer varies widely. It ranges from 250 ft. thick in parts of Georgia, to about 3,000 ft. thick in South Florida. Water from the Upper Floridan Aquifer is potable in most parts of the state and is a major source of groundwater for more than 11 million residents. However, in areas such as the far western panhandle and South Florida, where the Floridan Aquifer is very deep, the water is too salty to be potable. Instead, water from aquifers that lie above the Floridan is used for water supply.

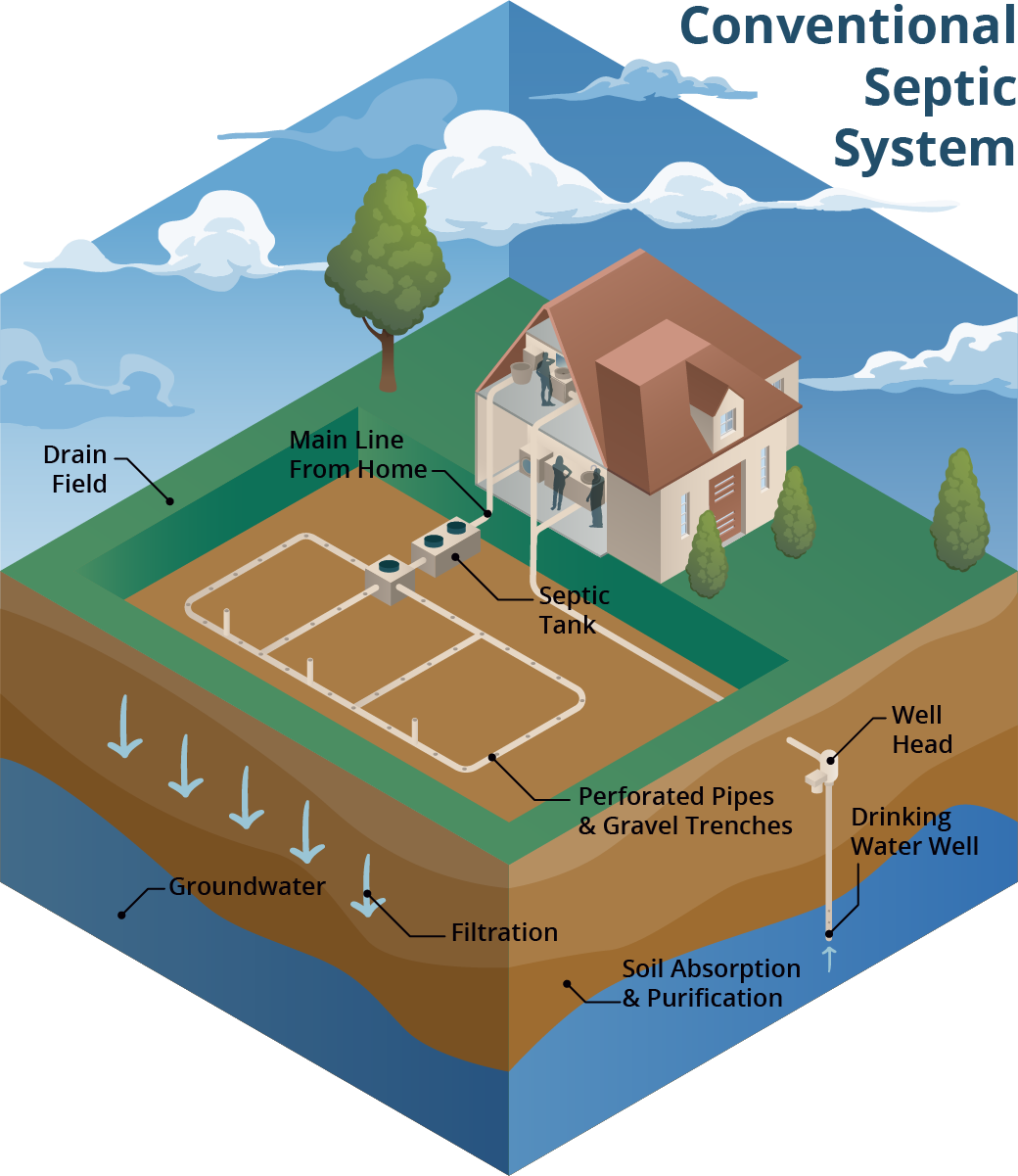

There are actually several major aquifer systems in Florida that lie on top of the Floridan Aquifer and are important sources of groundwater to local areas (Figure 2):

- The Sand and Gravel Aquifer in the far western panhandle is the main source of water for Santa Rosa and Escambia Counties. It is made up of of sand and gravel interbedded with layers of silt and clay.

- The Biscayne Aquifer supplies water to Dade and Broward Counties and southern Palm Beach County. A pipeline also transports water from this aquifer to the Florida Keys. The aquifer is made of permeable limestone and less permeable sand and sandstone.

- The Surficial Aquifer System (marked in green in the map in Figure 2) is the major source of drinking water in St. Johns, Flagler and Indian River counties, as well as Titusville and Palm Bay. It is typically shallow (less than 50 ft. thick) and is often referred to as a ‘water table’ aquifer, but in Indian River and St. Lucie Counties, it can be up to 400 ft. thick.

- Not included in Figure 2 is a fourth aquifer, the Intermediate Aquifer System in southwest Florida. It lies at a depth between the Surficial Aquifer System and the Floridan Aquifer. It is found south and east of Tampa, in Hillsborough and Polk counties and extends south through Collier County. It is the main source of water supply for Sarasota, Charlotte and Lee counties, where the underlying Floridan Aquifer is too salty to be potable.

Figure 2. A map of four major aquifer systems in the state of Florida at land surface. The Floridan Aquifer (in blue) underlies the entire state, but in areas north and east of Tampa it is found at the surface. The Surficial (green), Sand and Gravel (red), and Biscayne Aquifer (purple/pink) lie on top of the Floridan Aquifer. A confining unit (area in brown) consists of impermeable materials like thick layers of fine clay that prevent water from easily moving through it. Source: FDEP.

All of the aquifer systems in Florida are recharged by rainfall. In general, freshwater from deeper portions of the aquifer tends to have better water quality than surficial systems, since it is less susceptible to pollution from land surfaces. But, in areas where groundwater is excessively pumped or wells are drilled too deeply, saltwater intrusion occurs. This is where the underlying, denser saltwater replaces the pumped freshwater. Florida’s highly populated coastal areas are particularly susceptible to saltwater intrusion, and this is one of the main reasons that water conservation is a major priority in Florida.

More information about the Floridan Aquifer System and overlying aquifers can be found at the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (https://fldep.dep.state.fl.us/swapp/Aquifer.asp#P4) and in the UF EDIS Publication ‘Florida’s Water Reosurces’ by T. Borisova and T. Wade (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/fe757).

by Andrea Albertin | Jan 31, 2020

Contact you local county health department office for information on how to test your well water. Image: F. Alvarado Arce

Residents that rely on private wells for home consumption are responsible for ensuring the safety of their own drinking water. The Florida Department of Health (FDOH) recommends private well users test their water once a year for bacteria and nitrate.

Unlike private wells, public water supply systems in Florida are tested regularly to ensure that they are meeting safe drinking water standards.

Where can you have your well water tested?

Your best source of information on how to have your water tested is your local county health department. Most health departments test drinking water and they will let you know exactly what samples need to taken and ho w to submit a sample. You can also submit samples to a certified private lab near you.

Contact information for county health departments can be located at: http://www.floridahealth.gov/programs-and-services/county-health-departments/find-a-county-health-department/index.html

Contact information for private certified laboratories are found at https://fldeploc.dep.state.fl.us/aams/loc_search.asp

Why is it important to test for bacteria?

Labs commonly test for both total coliform bacteria and fecal coliforms (or E. coli specifically). This usually costs about $25 to $30, but can vary depending on where you have your sample analyzed.

- Coliform bacteria are a large, diverse group of bacteria and most species are harmless. But, a positive test for total coliforms shows that bacteria are getting into your well water. They are used as indicators – if coliform bacteria are present, other pathogens that cause diseases may also be getting into your well water. It is easier and cheaper to test for total coliforms than to test for a suite of bacteria and other organisms that can cause health problems.

- Fecal coliform bacteria are a subgroup of coliform bacteria found in human and other warm-blooded animal feces, in food and in the environment. E. coli are one group of fecal coliform bacteria. Most strains of E. coli are harmless, but some strains can cause diarrhea, urinary tract infections, and respiratory illnesses among others.

To ensure safe drinking water, FDOH strongly recommends disinfecting your well if the water tests positive for (1) only total coliform bacteria, or (2) both total coliform and fecal coliform bacteria (or E. coli). Disinfection is usually done through shock chlorination. You can either hire a well operator in your area to disinfect your well or you can do it yourself. Information for how to shock chlorinate your well can be found at http://www.floridahealth.gov/environmental-health/private-well-testing/_documents/well-water-facts-disinfection.pdf

Why is it important to test for nitrate concentration?

High levels of nitrate in drinking water can be dangerous to infants, and can cause “blue baby syndrome” or methemoglobinemia. This is where nitrate interferes with the blood’s capacity to carry oxygen. The Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL) allowed for nitrate in drinking water is 10 milligrams nitrate per liter of water (mg/L). It is particularly important to test for nitrate if you have a young infant in the home that is drinking well water or when well water is used to make formula to feed the infant.

If test results come back above 10 mg/L nitrate, use water from a tested source (bottled water or water from a public supply) until the problem is addressed. Nitrates in well water can come from fertilizers applied on land surfaces, animal waste and/or human sewage, such as from a septic tank. Have your well inspected by a professional to identify why elevated nitrate levels are in your well water. You can also consider installing a water treatment system, such as reverse osmosis or distillation units to treat the contaminated water. Before having a system installed, contact your local health department for more information.

In addition to once a year, you should also have your well water tested when:

- The color, taste or odor of your well water changes or if you suspect that someone became sick after drinking well water.

- A new well is drilled or if you have had maintenance done on your existing well

- A flood occurred and your well and/or septic tank were affected

Remember: Bacteria and nitrate are not the only parameters that well water is tested for. Call your local health department to discuss your what they recommend you should get the water tested for, because it can vary depending on where you live.

FDOH maintains an excellent website with many resources for private well users at http://www.floridahealth.gov/environmental-health/private-well-testing/index.html, which includes information on potential contaminants and how to maintain your well to ensure the quality of your well water.

by Andrea Albertin | May 3, 2019

The major goal of the Wakulla Springs Basin Management Action Plan (BMAP) is to reduce nitrogen loads to Wakulla Springs. Septic systems are identified as the primary source of this nitrogen. Photo: A. Albertin

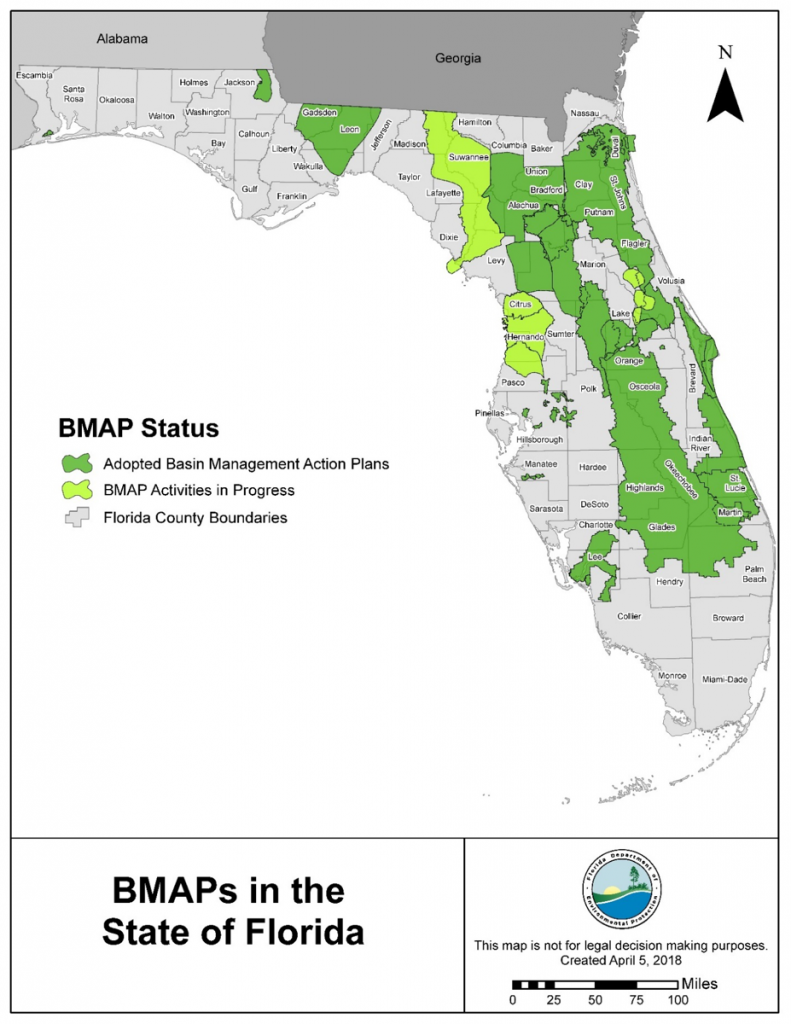

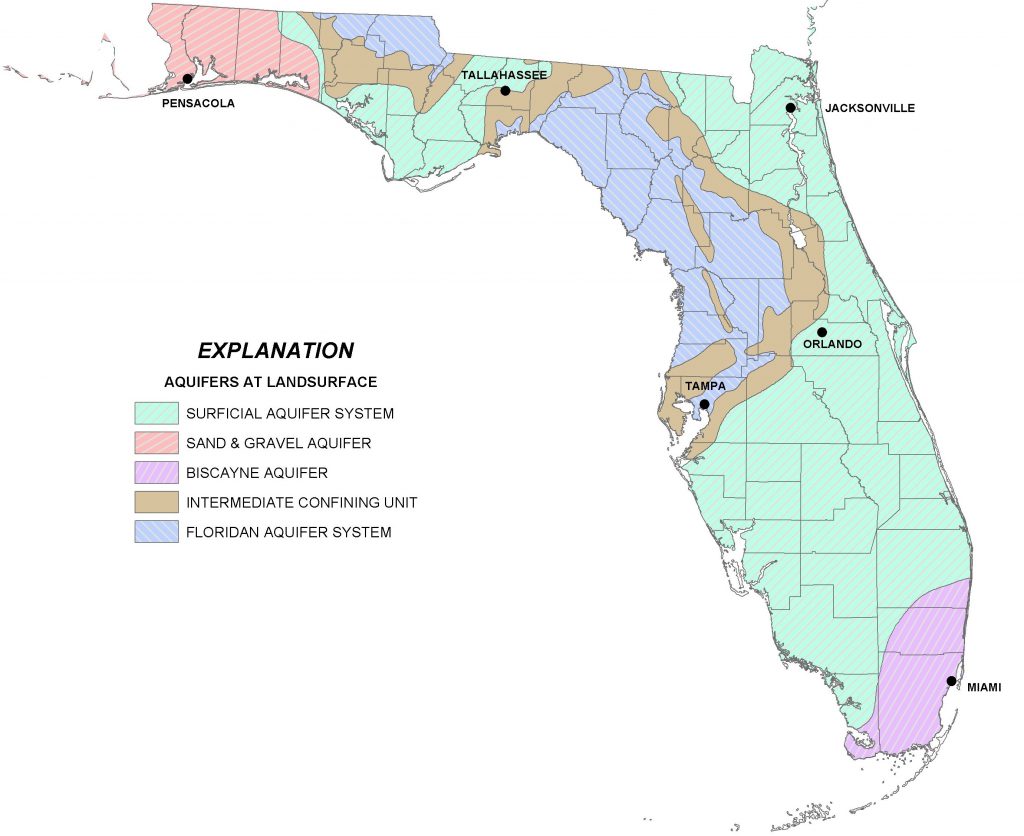

A Basin Management Action Plan, or BMAP, is a management plan developed for a waterbody (like a spring, river, lake, or estuary) that does not meet the water quality standards set by the state. One or more pollutants can impair a waterbody. In Florida, the most common pollutants are nutrients (particularly nitrate), pathogens (fecal coliform bacteria) and mercury.

The goal of the BMAP is to reduce the pollutant load to meet water quality standards set by the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP). BMAPS are roadmaps with a list of projects and management action items to reach these standards. FDEP develops them with stakeholder input. Targets are set at 20 years, and progress towards those targets is assessed every five years.

It’s important to understand that a BMAP encompasses the entire land area that contributes water to a given waterbody. For example, the land area that contributes water to Jackson Blue Springs and Merritts Mill Pond (either from surface waters or groundwater flow) is 154 square miles, while the Wakulla Springs Basin covers an area of 1,325 square miles.

BMAPs in the Panhandle

There are 33 adopted BMAPS in the state, and 5 that are pending adoption. Here in the Panhandle, we have three adopted BMAPS. They are the Bayou Chico BMAP in Escambia County, the Wakulla Springs BMAP in Wakulla, Leon, Gadsden and small parts of Jefferson County, and the Jackson Blue/Merritts Mill Pond BMAP in Jackson County. All three are impaired for different reasons.

- Bayou Chico discharges into Pensacola Bay and is polluted by fecal coliform bacteria. The BMAP addresses ways to reduce coliforms from humans and pets, which includes sewer expansion projects, stormwater runoff management, septic tank inspections, pet waste ordinances and a Clean Marina and Boatyard program.

- Wakulla Springs Nitrate from human waste is the main pollutant to Wakulla Springs, and Tallahassee’s wastewater treatment facility and the city’s Southeast Sprayfield were identified as the main sources. Both sites were upgraded (the sprayfield was moved), greatly reducing nitrate contributions to the spring basin. The BMAP is focused on septic systems and septic to sewer hookups.

- Jackson Blue/Merritts Mill Pond Nitrate is also the primary pollutant to the Jackson Blue/Merritts Mill Pond Basin, but nitrogen fertilizer from agriculture is identified as the main source. This BMAP focuses on farmers implementing Best Management Practices (BMPs), land acquisition by the Northwest Florida Water Management District , as well as septic tanks, recognizing their nitrogen contribution to Merritts Mill Pond.

Once all the BMAPS are adopted, FDEP states that almost 14 million acres will be under active basin management, an area that includes more than 6.5 million Floridians.

Adopted and pending BMAPS in Florida. Source: FDEP Statewide Annual Report, June 2018

How are residents living in an area with a BMAP affected? It varies by BMAP and specifically land use within its boundaries. For example, in BMAPs where nitrogen from septic systems are found to be a major source of nutrient impairment to a water body, septic to sewer hookups, or septic system upgrades to more advanced treatment units will be required in specific areas. In urban areas where nitrogen fertilizer is an important source, municipalities are required to adopt fertilizer ordinances. Where nitrogen fertilizer from agricultural production is a major source of impairment, producers are required to implement Best Management Practices to reduce nitrogen loads.

More information about BMAPS

For specific information on BMAPS, FDEP has an excellent website: https://floridadep.gov/dear/water-quality-restoration/content/basin-management-action-plans-bmaps All BMAPs (full reports with specific action items listed) can be found there, along with maps, information about upcoming meetings and webinars and other pertinent information.

Your local Health Department Office is the best resource regarding septic systems and any ordinances that may apply to you depending on where you live. Your Water Management District (in the Panhandle it’s the Northwest Florida Water Management District) is also an excellent resource and staff can let you know whether or not you live or farm in an area with a BMAP and how that may affect you.