by Andrea Albertin | Oct 2, 2020

If your private well was damaged or flooded due to hurricane or other heavy storm activity, your well water may not be safe to drink. Well water should not be used for drinking, cooking purposes, making ice, brushing teeth or bathing until it is tested by a certified laboratory for total coliform bacteria and E. coli.

Residents should use bottled, boiled or treated water until their well water has been tested and deemed safe.

- Boiling: To make water safe for drinking, cooking or washing, bring it to a rolling boil for at least one minute to kill organisms and then allow it to cool.

- Disinfecting with bleach: If boiling isn’t possible, add 1/8 of a teaspoon or about 8 drops of fresh unscented household bleach (4 to 6% active ingredient) per gallon of water. Stir well and let stand for 30 minutes. If the water is cloudy after 30 minutes, repeat the procedure once.

- Keep treated or boiled water in a closed container to prevent contamination

Use bottled water for mixing infant formula.

Where can you have your well water tested?

Contact your county health department for information on how to have your well water tested. Image: F. Alvarado Arce

Most county health departments accept water samples for testing. Contact your local department for information about what to have your water tested for (they may recommend more than just bacteria), and how to collect and submit the sample.

Contact information for Florida Health Departments can be found here: County Health Departments – Location Finder

You can also submit samples to a certified commercial lab near you. Contact information for commercial laboratories that are certified by the Florida Department of Health are found here: Laboratories certified by FDOH

This site includes county health department labs, commercial labs as well as university labs. You can search by county.

What should you do if your well water sample tests positive for bacteria?

The Florida Department of Health recommends well disinfection if water samples test positive for total coliform bacteria or for both total coliform and E. coli, a type of fecal coliform bacteria.

You can hire a local licensed well operator to disinfect your well, or if you feel comfortable, you can shock chlorinate the well yourself.

You can find information on how to shock chlorinate your well at:

After well disinfection, you need to have your well water re-tested to make sure it is safe to use. If it tests positive again for total coliform bacteria or both total coliform and E. coli call a licensed well operator to have the well inspected to get to the root of the problem.

Well pump and electrical system care

If the pump and/or electrical system have been underwater and are not designed to be used underwater, do not turn on the pump. There is a potential for electrical shock or damage to the well or pump. Stay away from the well pump while flooded to avoid electric shock.

Once the floodwaters have receded and the pump and electrical system have dried, a qualified electrician, well operator/driller or pump installer should check the wiring system and other well components.

Remember: You should have your well water tested at any time when:

- A flood occurred and your well was affected

- The color, taste or odor of your well water changes or if you suspect that someone became sick after drinking your well water.

- A new well is drilled or if you have had maintenance done on your existing well

- There has been any type of chemical spill (pesticides, fuel, etc.) into or near your well

The Florida Department of Health maintains an excellent website with many resources for private well users: FDOH Private Well Testing and other Reosurces which includes information on potential contaminants and how to maintain your well to ensure the quality of your well water.

by Andrea Albertin | Apr 9, 2020

Pitt Spring in the Florida Panhandle is one of more than 1,000 freshwater springs in the state. Springs serve as ‘windows’ to groundwater quality, since the water that flows from them comes largely from the Upper Floridan Aquifer. Photo: A. Albertin

As Florida residents, we are so fortunate to have the Floridan Aquifer lying below us, one of the most productive aquifer systems in the world. The aquifer underlies an area of about 100,000 square miles that includes all of Florida and extends into parts of Alabama, Georgia and South Carolina, as well as parts of the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico (Figure 1). The Floridan Aquifer consists of the Upper and Lower Floridan Aquifer.

Figure 1. Map of the extent of the Floridan Aquifer. Areas in gray show where the aquifer is buried deep below the land surface, while areas in light brown indicate where the aquifer is at land surface. Many springs in Florida are found in these light brown areas. Source: USGS Publication HA 730-G.

Aquifers are immense underground zones of permeable rocks, rock fractures and unconsolidated (or loose) material, like sand, silt and clay that hold water and allow water to move through them. Both fresh and saltwater fill the pores, fissures and conduits of the Floridan Aquifer. Saltwater, which is more dense than freshwater, is found in all areas of the deeper aquifer below the freshwater.

The thickness of the Floridan Aquifer varies widely. It ranges from 250 ft. thick in parts of Georgia, to about 3,000 ft. thick in South Florida. Water from the Upper Floridan Aquifer is potable in most parts of the state and is a major source of groundwater for more than 11 million residents. However, in areas such as the far western panhandle and South Florida, where the Floridan Aquifer is very deep, the water is too salty to be potable. Instead, water from aquifers that lie above the Floridan is used for water supply.

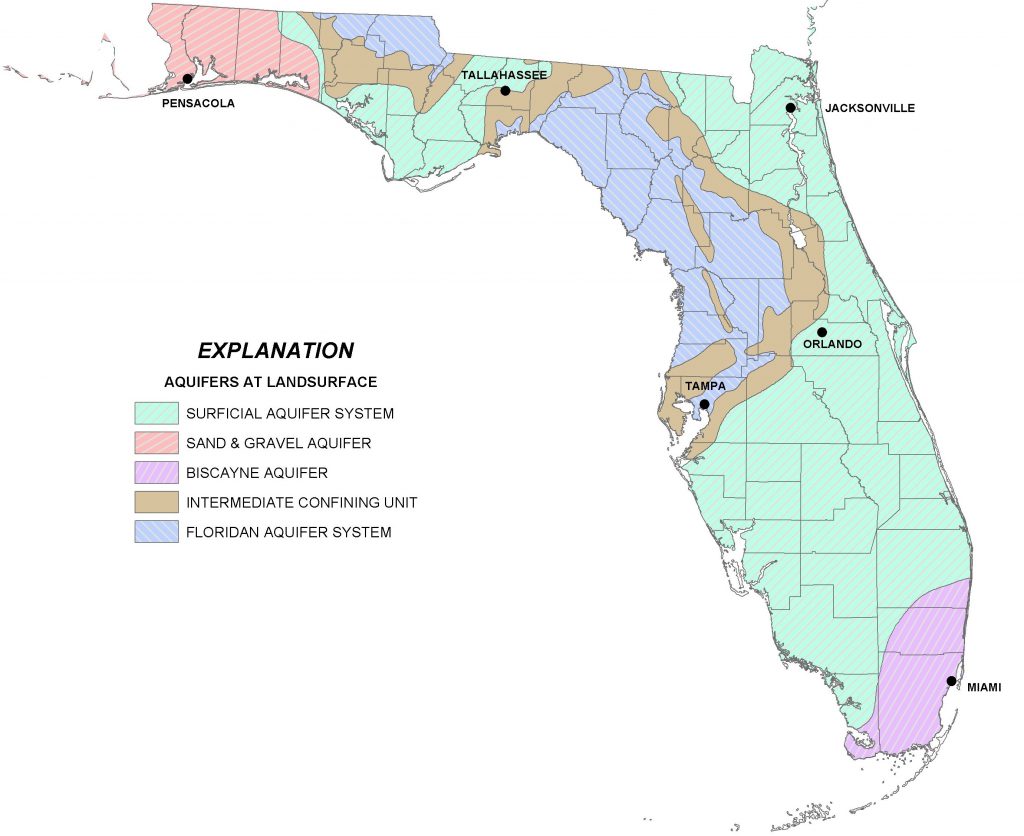

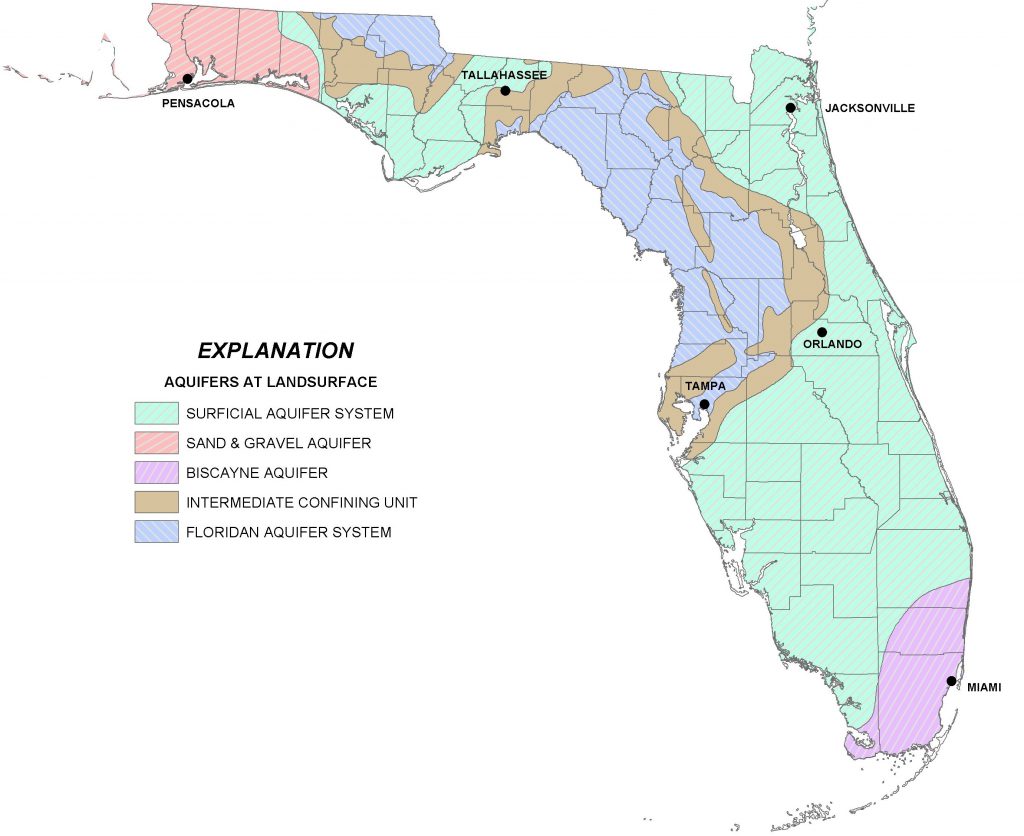

There are actually several major aquifer systems in Florida that lie on top of the Floridan Aquifer and are important sources of groundwater to local areas (Figure 2):

- The Sand and Gravel Aquifer in the far western panhandle is the main source of water for Santa Rosa and Escambia Counties. It is made up of of sand and gravel interbedded with layers of silt and clay.

- The Biscayne Aquifer supplies water to Dade and Broward Counties and southern Palm Beach County. A pipeline also transports water from this aquifer to the Florida Keys. The aquifer is made of permeable limestone and less permeable sand and sandstone.

- The Surficial Aquifer System (marked in green in the map in Figure 2) is the major source of drinking water in St. Johns, Flagler and Indian River counties, as well as Titusville and Palm Bay. It is typically shallow (less than 50 ft. thick) and is often referred to as a ‘water table’ aquifer, but in Indian River and St. Lucie Counties, it can be up to 400 ft. thick.

- Not included in Figure 2 is a fourth aquifer, the Intermediate Aquifer System in southwest Florida. It lies at a depth between the Surficial Aquifer System and the Floridan Aquifer. It is found south and east of Tampa, in Hillsborough and Polk counties and extends south through Collier County. It is the main source of water supply for Sarasota, Charlotte and Lee counties, where the underlying Floridan Aquifer is too salty to be potable.

Figure 2. A map of four major aquifer systems in the state of Florida at land surface. The Floridan Aquifer (in blue) underlies the entire state, but in areas north and east of Tampa it is found at the surface. The Surficial (green), Sand and Gravel (red), and Biscayne Aquifer (purple/pink) lie on top of the Floridan Aquifer. A confining unit (area in brown) consists of impermeable materials like thick layers of fine clay that prevent water from easily moving through it. Source: FDEP.

All of the aquifer systems in Florida are recharged by rainfall. In general, freshwater from deeper portions of the aquifer tends to have better water quality than surficial systems, since it is less susceptible to pollution from land surfaces. But, in areas where groundwater is excessively pumped or wells are drilled too deeply, saltwater intrusion occurs. This is where the underlying, denser saltwater replaces the pumped freshwater. Florida’s highly populated coastal areas are particularly susceptible to saltwater intrusion, and this is one of the main reasons that water conservation is a major priority in Florida.

More information about the Floridan Aquifer System and overlying aquifers can be found at the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (https://fldep.dep.state.fl.us/swapp/Aquifer.asp#P4) and in the UF EDIS Publication ‘Florida’s Water Reosurces’ by T. Borisova and T. Wade (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/fe757).

by Andrea Albertin | Jan 31, 2020

Contact you local county health department office for information on how to test your well water. Image: F. Alvarado Arce

Residents that rely on private wells for home consumption are responsible for ensuring the safety of their own drinking water. The Florida Department of Health (FDOH) recommends private well users test their water once a year for bacteria and nitrate.

Unlike private wells, public water supply systems in Florida are tested regularly to ensure that they are meeting safe drinking water standards.

Where can you have your well water tested?

Your best source of information on how to have your water tested is your local county health department. Most health departments test drinking water and they will let you know exactly what samples need to taken and ho w to submit a sample. You can also submit samples to a certified private lab near you.

Contact information for county health departments can be located at: http://www.floridahealth.gov/programs-and-services/county-health-departments/find-a-county-health-department/index.html

Contact information for private certified laboratories are found at https://fldeploc.dep.state.fl.us/aams/loc_search.asp

Why is it important to test for bacteria?

Labs commonly test for both total coliform bacteria and fecal coliforms (or E. coli specifically). This usually costs about $25 to $30, but can vary depending on where you have your sample analyzed.

- Coliform bacteria are a large, diverse group of bacteria and most species are harmless. But, a positive test for total coliforms shows that bacteria are getting into your well water. They are used as indicators – if coliform bacteria are present, other pathogens that cause diseases may also be getting into your well water. It is easier and cheaper to test for total coliforms than to test for a suite of bacteria and other organisms that can cause health problems.

- Fecal coliform bacteria are a subgroup of coliform bacteria found in human and other warm-blooded animal feces, in food and in the environment. E. coli are one group of fecal coliform bacteria. Most strains of E. coli are harmless, but some strains can cause diarrhea, urinary tract infections, and respiratory illnesses among others.

To ensure safe drinking water, FDOH strongly recommends disinfecting your well if the water tests positive for (1) only total coliform bacteria, or (2) both total coliform and fecal coliform bacteria (or E. coli). Disinfection is usually done through shock chlorination. You can either hire a well operator in your area to disinfect your well or you can do it yourself. Information for how to shock chlorinate your well can be found at http://www.floridahealth.gov/environmental-health/private-well-testing/_documents/well-water-facts-disinfection.pdf

Why is it important to test for nitrate concentration?

High levels of nitrate in drinking water can be dangerous to infants, and can cause “blue baby syndrome” or methemoglobinemia. This is where nitrate interferes with the blood’s capacity to carry oxygen. The Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL) allowed for nitrate in drinking water is 10 milligrams nitrate per liter of water (mg/L). It is particularly important to test for nitrate if you have a young infant in the home that is drinking well water or when well water is used to make formula to feed the infant.

If test results come back above 10 mg/L nitrate, use water from a tested source (bottled water or water from a public supply) until the problem is addressed. Nitrates in well water can come from fertilizers applied on land surfaces, animal waste and/or human sewage, such as from a septic tank. Have your well inspected by a professional to identify why elevated nitrate levels are in your well water. You can also consider installing a water treatment system, such as reverse osmosis or distillation units to treat the contaminated water. Before having a system installed, contact your local health department for more information.

In addition to once a year, you should also have your well water tested when:

- The color, taste or odor of your well water changes or if you suspect that someone became sick after drinking well water.

- A new well is drilled or if you have had maintenance done on your existing well

- A flood occurred and your well and/or septic tank were affected

Remember: Bacteria and nitrate are not the only parameters that well water is tested for. Call your local health department to discuss your what they recommend you should get the water tested for, because it can vary depending on where you live.

FDOH maintains an excellent website with many resources for private well users at http://www.floridahealth.gov/environmental-health/private-well-testing/index.html, which includes information on potential contaminants and how to maintain your well to ensure the quality of your well water.

by Andrea Albertin | May 3, 2019

The major goal of the Wakulla Springs Basin Management Action Plan (BMAP) is to reduce nitrogen loads to Wakulla Springs. Septic systems are identified as the primary source of this nitrogen. Photo: A. Albertin

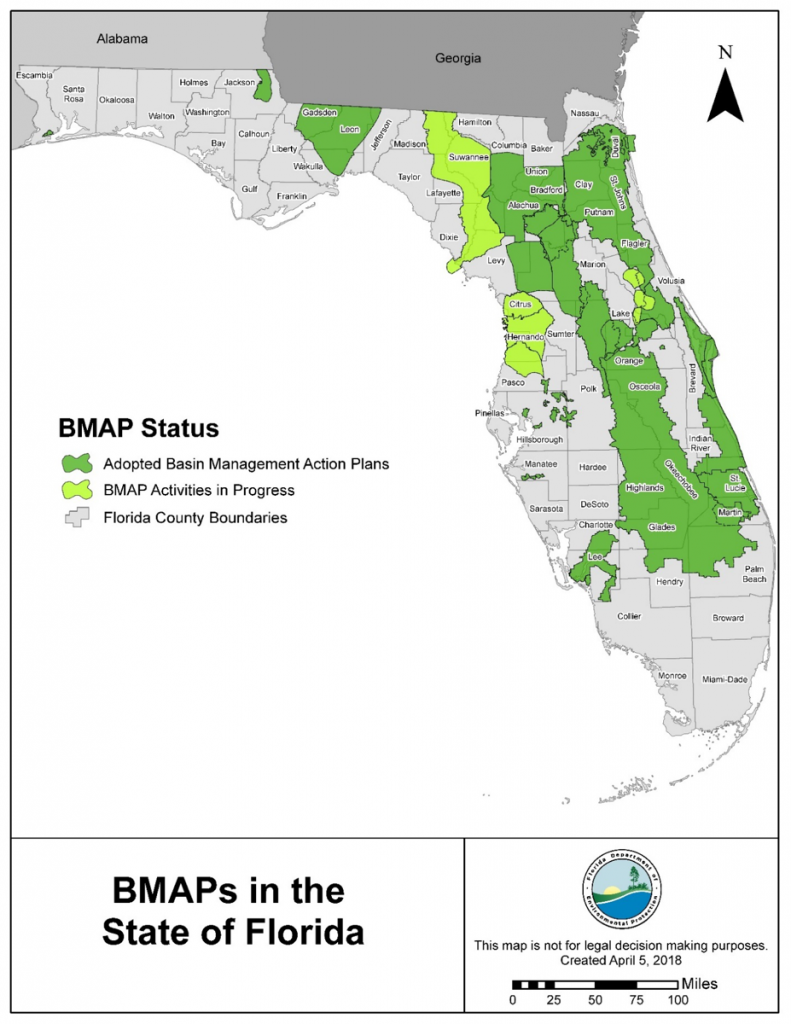

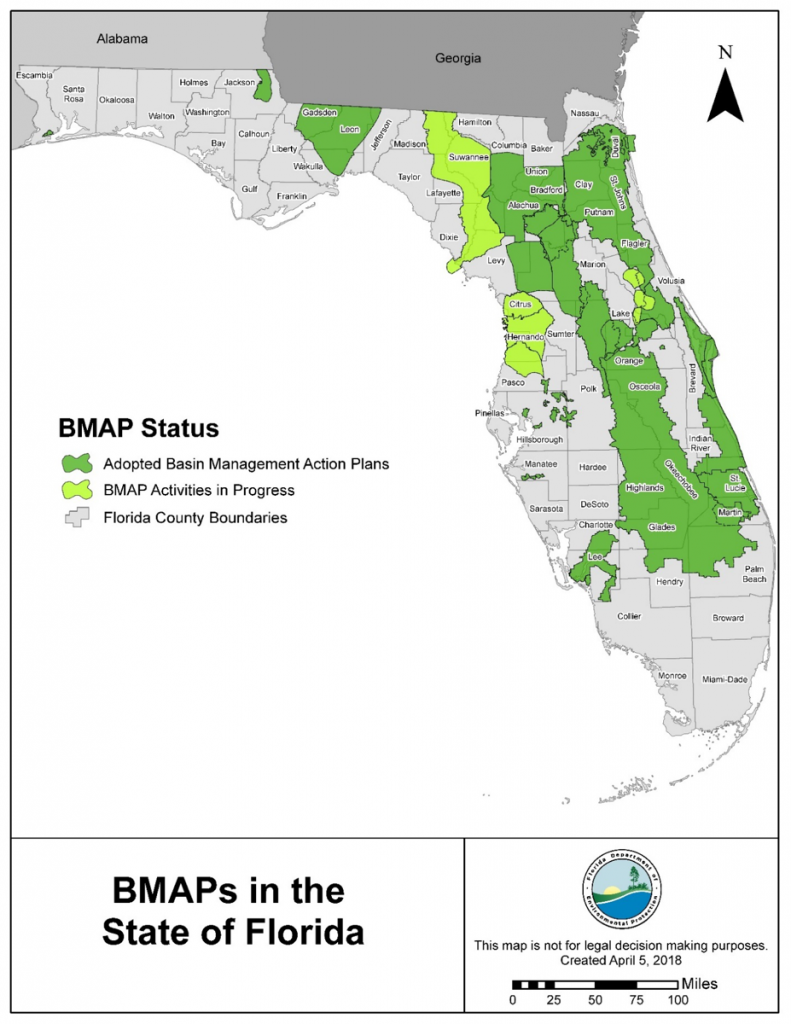

A Basin Management Action Plan, or BMAP, is a management plan developed for a waterbody (like a spring, river, lake, or estuary) that does not meet the water quality standards set by the state. One or more pollutants can impair a waterbody. In Florida, the most common pollutants are nutrients (particularly nitrate), pathogens (fecal coliform bacteria) and mercury.

The goal of the BMAP is to reduce the pollutant load to meet water quality standards set by the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP). BMAPS are roadmaps with a list of projects and management action items to reach these standards. FDEP develops them with stakeholder input. Targets are set at 20 years, and progress towards those targets is assessed every five years.

It’s important to understand that a BMAP encompasses the entire land area that contributes water to a given waterbody. For example, the land area that contributes water to Jackson Blue Springs and Merritts Mill Pond (either from surface waters or groundwater flow) is 154 square miles, while the Wakulla Springs Basin covers an area of 1,325 square miles.

BMAPs in the Panhandle

There are 33 adopted BMAPS in the state, and 5 that are pending adoption. Here in the Panhandle, we have three adopted BMAPS. They are the Bayou Chico BMAP in Escambia County, the Wakulla Springs BMAP in Wakulla, Leon, Gadsden and small parts of Jefferson County, and the Jackson Blue/Merritts Mill Pond BMAP in Jackson County. All three are impaired for different reasons.

- Bayou Chico discharges into Pensacola Bay and is polluted by fecal coliform bacteria. The BMAP addresses ways to reduce coliforms from humans and pets, which includes sewer expansion projects, stormwater runoff management, septic tank inspections, pet waste ordinances and a Clean Marina and Boatyard program.

- Wakulla Springs Nitrate from human waste is the main pollutant to Wakulla Springs, and Tallahassee’s wastewater treatment facility and the city’s Southeast Sprayfield were identified as the main sources. Both sites were upgraded (the sprayfield was moved), greatly reducing nitrate contributions to the spring basin. The BMAP is focused on septic systems and septic to sewer hookups.

- Jackson Blue/Merritts Mill Pond Nitrate is also the primary pollutant to the Jackson Blue/Merritts Mill Pond Basin, but nitrogen fertilizer from agriculture is identified as the main source. This BMAP focuses on farmers implementing Best Management Practices (BMPs), land acquisition by the Northwest Florida Water Management District , as well as septic tanks, recognizing their nitrogen contribution to Merritts Mill Pond.

Once all the BMAPS are adopted, FDEP states that almost 14 million acres will be under active basin management, an area that includes more than 6.5 million Floridians.

Adopted and pending BMAPS in Florida. Source: FDEP Statewide Annual Report, June 2018

How are residents living in an area with a BMAP affected? It varies by BMAP and specifically land use within its boundaries. For example, in BMAPs where nitrogen from septic systems are found to be a major source of nutrient impairment to a water body, septic to sewer hookups, or septic system upgrades to more advanced treatment units will be required in specific areas. In urban areas where nitrogen fertilizer is an important source, municipalities are required to adopt fertilizer ordinances. Where nitrogen fertilizer from agricultural production is a major source of impairment, producers are required to implement Best Management Practices to reduce nitrogen loads.

More information about BMAPS

For specific information on BMAPS, FDEP has an excellent website: https://floridadep.gov/dear/water-quality-restoration/content/basin-management-action-plans-bmaps All BMAPs (full reports with specific action items listed) can be found there, along with maps, information about upcoming meetings and webinars and other pertinent information.

Your local Health Department Office is the best resource regarding septic systems and any ordinances that may apply to you depending on where you live. Your Water Management District (in the Panhandle it’s the Northwest Florida Water Management District) is also an excellent resource and staff can let you know whether or not you live or farm in an area with a BMAP and how that may affect you.

by Andrea Albertin | Mar 20, 2019

By Vance Crain and Andrea Albertin

Fisherman with a large Shoal Bass in the Apalachicola-Chattahootchee-Flint River Basin. Photo credit: S. Sammons

Along the Chipola River in Florida’s Panhandle, farmers are doing their part to protect critical Shoal Bass habitat by implementing agricultural Best Management Practices (BMPs) that reduce sediment and nutrient runoff, and help conserve water.

Florida’s Shoal Bass

Lurking in the clear spring-fed Chipola River among limerock shoals and eel grass, is a predatory powerhouse, perfectly camouflaged in green and olive with tiger stripes along its body. The Shoal Bass (a species of Black Bass) tips the scale at just under 6 lbs. But what it lacks in size, it makes up for in power. Unlike any other bass, and found nowhere else in Florida, anglers travel long distances for a chance to pursue it. Floating along the swift current, rocks, and shoals will make you feel like you’ve been transported hundreds of miles away to the Georgia Piedmont, and it’s only the Live Oaks and palms overhanging the river that remind you that you’re still in Florida, and in a truly unique place.

Native to only one river basin in the world, the Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint (ACF) River Basin, habitat loss is putting this species at risk. The Shoal Bass is a fluvial specialist, which means it can only survive in flowing water. Dams and reservoirs have eliminated habitat and isolated populations. Sediment runoff into waterways smothers habitat and prevents the species from reproducing.

In the Chipola River, the population is stable but its range is limited. Some of the most robust Shoal Bass numbers are found in a 6.5-mile section between the Peacock Bridge and Johnny Boy boat ramp. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission has turned this section into a Shoal Bass catch and release only zone to protect the population. However, impacts from agricultural production and ranching, like erosion and nutrient runoff can degrade the habitat needed for the Shoal Bass to spawn.

Preferred Shoal Bass habitat, a shoal in the Chipola River. Photo credit: V. Crain

Shoal Bass habitat conservation and BMPs

In 2010, the Southeast Aquatic Resources Partnership (SARP), the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation and a group of scientists (the Black Bass Committee) developed the Native Black Bass Initiative. The goal of the initiative is to increase research and the protection of three Black Bass species native to the Southeast, including the Shoal Bass. It also defined the Shoal Bass as a keystone species, meaning protection of this apex predators’ habitat benefits a host of other threatened and endangered species.

Along the Chipola River, farmers are teaming up with SARP and other partners to protect Shoal Bass habitat and improve farming operations through BMP implementation. A major goal is to protect the river’s riparian zones (the areas along the borders). When healthy, these areas act like sponges by absorbing nutrients and sediment runoff. Livestock often degrade riparian zones by trampling vegetation and destroying the streambank when they go down to a river to drink. Farmers are installing alternative water supplies, like water wells and troughs in fields, and fencing out cattle from waterways to protect these buffer areas and improve water quality. Row crop farmers are helping conserve water in the river basin by using advanced irrigation technologies like soil moisture sensors to better inform irrigation scheduling and variable rate irrigation to increase irrigation efficiency. Cost-share funding from SARP, the USDA-NRCS and FDACS provide resources and technical expertise for farmers to implement these BMPs.

Holstein drinking from a water trough in the field, instead of going down to the river to get water which can cause erosion and problems with water quality. Photo credit: V. Crain

By working together in the Chipola River Basin, farmers, fisheries scientists and resource managers are helping ensure that critical habitat for Shoal Bass remains healthy. Not only is this important for the species and resource, but it will ensure that future generations can continue to enjoy this unique river and seeing one of these fish. So the next time you catch a Shoal Bass, thank a farmer.

For more information about BMPs and cost-share opportunities available for farmers and ranchers, contact your local FDACS field technician: https://www.freshfromflorida.com/Divisions-Offices/Agricultural-Water-Policy/Organization-Staff and NRCS field office USDA-NRCS field office: https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/main/fl/contact/local/ For questions regarding the Native Black Bass Initiative or Shoal Bass habitat conservation, contact Vance Crain at vance@southeastaquatics.net

Vance Crain is the Native Black Bass Initiative Coordinator for the Southeast Aquatic Resource Partnership (SARP).

by Erik Lovestrand | Aug 3, 2018

If you have not seen the news yet, the US Supreme Court provided a ruling on June 27, 2018 regarding the decades-long conflict between Florida and Georgia over water use in the Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint tri-state river basin. Guess what; the battle continues. Following the previous findings of the court-appointed Special Master and his recommendation to deny Florida relief in the dispute, there were many disappointed people south of the border between the two states. The recent decision to remand the case back to the Special Master for further consideration has taken many by surprise; happy surprise south of the border and not so happy as you look northward (unless you talk to the attorneys litigating the case, maybe).

The resulting decision kept Florida’s hopes alive for an equitable allocation of water resources in the basin that spans nearly 20,000 square miles of the Southeastern US. At stake, from Florida’s perspective, is the productivity and ecosystem integrity of the Apalachicola River and Bay ecosystem. For Georgia, enough water to supply its growing population and thirsty agricultural interests in the Flint River Basin south of Atlanta.

The Court’s 5–4 decision, found that the Special Master had applied too high a standard regarding “harm and redressability” for Florida’s claims. They ordered the case to be reheard so that appropriate considerations could be given to Florida’s arguments. “The amount of extra water that reaches the Apalachicola may significantly redress the economic and ecological harm that Florida has suffered,” said Justice Breyer, who was joined by Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Anthony Kennedy, Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Sonya Sotomayor. “Further findings, however, are needed.”

The Court’s opinion does not actually outline any specific solutions for the water battle, and it in no way guarantees a win for Florida, but it does keep the legal challenge alive – along with the hope of better days for Florida’s oyster industry, which has suffered a major fisheries collapse that began around 2012. Visit this link if you would like to read the syllabus, as well as the full opinion of the High Court.

We should all consider the magnitude of the importance of the Apalachicola River and Bay for our region, due to its connection to the larger Gulf of Mexico. Estuaries like this are crucial links in the life-stages of countless marine organisms, including many we depend on for food and recreation. Blue crabs migrate tremendous distances to spawn in our near shore estuaries. Their young then disperse to populate large areas of coastline. Post-larval shrimp move into our estuaries to grow up after being spawned offshore. Later they swim out as adults to begin the cycle again. It is no wonder the shorelines of our Florida estuaries are dotted with prehistoric shell middens from peoples who thrived near these resource-rich ecosystems. Who knows if the Apalachicola Bay will ever recover to the productivity of its glory days, when a hard-working person could harvest 20 bags of oysters in a day? Regardless, we should all be thankful for what Apalachicola Bay has meant to so many generations of people over such a wide expanse of our Northern Gulf of Mexico coastline. Take just a moment to think about it, please.