by Dana Stephens | Nov 17, 2025

What are PFAS?

PFAS are per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. PFAS is a class of chemicals found in various industrial and consumer goods. For instance, you may find them in food packaging, textiles, cosmetics, and frequently in aqueous film-forming foams (AFFFs) used to extinguish fires. PFAS chemicals are known for repelling grease, water, and stains, making them widely used in various applications. These chemicals are stable and persistent, earning them the nickname “forever chemicals” because they do not readily biodegrade, or break down easily in the environment.

Numerous researchers suggested PFAS are abundant in aquatic systems and toxic to a range of aquatic organisms, with additional concerns of bioaccumulation of PFAS. PFAS accumulate in sediments and aquatic organisms, which pose health risks to wildlife and humans through the food chain. Research suggests linkages of PFAS to disruption of endocrine function, reproduction, and development in aquatic organisms. Research suggests similar linkages of PFAS to humans, like increased cancer risk, immune system suppression, endocrine and reproductive disruption, and child developmental concerns.

The United States Geological Survey (USGS) estimated that at least 45% of the United States’ tap water has one or more PFAS chemicals (Smalling et al. 2023). At least one PFAS was identified in 60% of public wells and 20% of domestic wells supplying drinking water in the eastern United States (McMahon et al. 2022).

Have PFAS been found in Santa Rosa County drinking water and surface waters?

Measured PFAS in Florida and Santa Rosa County Drinking Waters

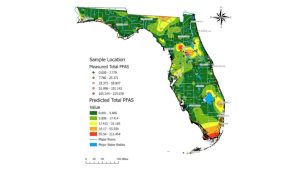

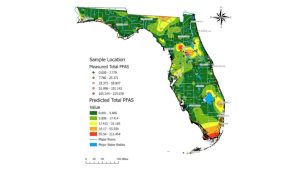

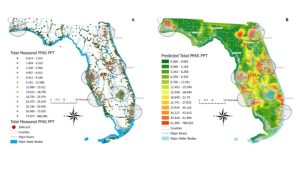

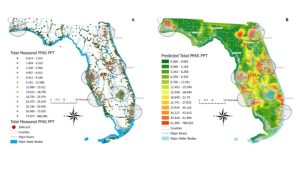

Figure 1. Map with measured total PFAS in drinking water samples across a gradient of low concentrations (green dots) to medium concentrations (yellow dots) to higher concentrations (red dots). Shaded map colors are the predicted total PFAS using estimated values of PFAS concentrations from low (green) to high (red). Data, figure, and result interpolation from Sinkway et al. 2024.

A team of researchers completed a comprehensive statewide assessment of PFAS in Florida drinking water (Sinkway et al. 2024). The team collected 448 drinking water samples across all 67 Florida counties. The drinking water samples were analyzed for 31 PFAS, where 19 PFAS were found in at least one drinking water sample. The top five most frequently detected PFAS across Florida were 6:2 fluorotelomer sulfonate (6:2 FTS) (in 84% of the samples analyzed), Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) (65%), linear perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) (65%), branched PFOS (64%), and perfluorobutane sulfonic acid (PFBS).

A total of 107 taps had PFOA or PFOS concentrations above 4 ng/L (ppt), where the maximum total PFAS concentration in a tap was 219 ng/L. A maximum contaminant level for PFOA and PFOS of 4 ng/L was implemented by the United States Environmental Protection Agency National Primary Drinking Water Regulation as of May 14, 2025 (USEPA, 2025). Overall, 8% of the drinking water samples analyzed exceeded 4 ng/L for PFOA and 16% for PFOS. The average total PFAS in city water was 15.6 ng/L, and in well water was 4.5 ng/L across Florida.

Santa Rosa County was not ranked in the 12 Florida counties with the highest maximum and average total PFAS concentrations (ng/L) or the lowest maximum and average total PFAS concentrations (ng/L) in drinking water (Table 1). Santa Rosa ranked 34th for the highest maximum total PFAS concentration and 35th for the highest average total PFAS concentration among the 67 Florida counties. Among the 25 drinking water samples collected, the maximum total PFAS concentration measured was 15 ng/L with an average total PFAS of 4.8 ng/L among the drinking water samples.

Table 1. The 12 Florida counties with highest and lowest total PFAS drinking water concentrations (ng/L). Data, figure, and result interpolation from Sinkway et al. 2024.

Measured PFAS in Florida and Santa Rosa County Surface Waters

A team of researchers completed a comprehensive statewide assessment of PFAS in Florida surface waters (Camacho et al. 2024). A network of citizen scientists collected 2,323 surface water samples across the 67 Florida counties. These surface water samples were analyzed for 50 PFAS, with 33 PFAS being detected in at least one surface water sample across Florida. The top five most frequently detected PFAS were perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) (94% of the samples), perfluorobutane sulfonic acid (PFBS) (65%), perfluorohexanoic acid (PFHxA) (61%), perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA) (54%), and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) (53%).

There were 915 surface water samples (39%) with PFOA concentrations above 4 ng/L and 920 samples (40%) with PFOS above 4 ng/L. All counties had at least one sample with PFOA, 96% had PFNA, 93% had PFBS, 91% had PFOS, and 82% of counties had PFHxA. The average PFAS detected among counties ranged from 2 ng/L of PFNA to 10 ng/L of PFOS. The maximum PFAS detected among counties ranged from 81 ng/L of PFOA to 1135 ng/L of PFOS.

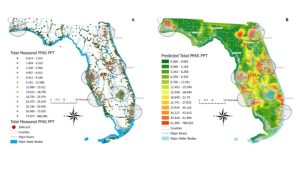

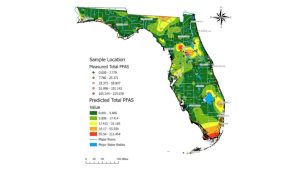

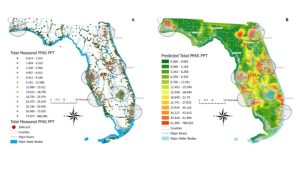

Figure 2. Surface water sampled sites with detected PFAS, where the dots’ color represents the total PFAS concentration measured. Map B shows predicted PFAS levels based on measured total PFAS concentrations in surface water samples. Note that these values do not represent predicted PFAS concentrations on land. Data, figure, and result interpolation from Camacho et al. 2024.

A total of 36 surface water samples were collected in Santa Rosa County (Figure 2). Santa Rosa County ranked 31stamong Florida counties with 7 surface water samples (7 samples out of 36 total or 19%) with PFOA above 4 ng/L. Santa Rosa County ranked 26th for the number of samples with 8 samples (22%) above 4 ng/L for PFOS. The average total PFAS concentration detected in a surface water sample was 6 ng/L, while the maximum total PFAS concentration detected in a sample was 29 ng/L.

Dr. Bowden, with the University of Florida’s College of Veterinary Medicine and Chemistry Department, led the PFAS research shared here. Dr. Bowden has extensive information on the Bowden Lab website (https://www.bowdenlaboratory.com/dr-bowden.html), including an interactive map of all the PFAS surface water samples collected in Florida. Select Okaloosa County under the filter section to see the surface water samples and learn more about the PFAS information for each sample collected in Okaloosa County (https://www.bowdenlaboratory.com/florida-surface-water.html).

What does this mean for Santa Rosa County?

PFAS have been detected in drinking water and surface waters in Santa Rosa County. Although not the highest concentrations across the state, there were drinking and surface water samples exceeding USEPA’s 4 ng/L contaminant level standard. Understanding what PFAS are and joining in educational conversations about PFAS helps our community. Efforts that support continued sampling and extended monitoring also increase our understanding of PFAS concentrations in Santa Rosa County’s drinking and surface waters. If you want to learn more about PFAS or join community scientists’ efforts to expand PFAS water monitoring, please contact Dana Stephens, Florida Sea Grant Extension Agent with the UF/IFAS Okaloosa County Extension Office.

References

Camacho, C.G., et al. 2024. Statewide surveillance and mapping of PFAS in Florida surface waters. American Chemical Society, 4: 434-4355. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsestwater

United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). 2025. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) final PFAS national primary drinking water regulation. https://www.epa.gov/sdwa/and-polyfluoroalkyl-substances-pfas

McMahon, P.B., Tokranov, A.K., and Bexfield, L.M. 2022. Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances in groundwater used as a source of drinking water in the Eastern United States. Environmental Science and Technology 56(4): 2279-2288. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.1c04795

Skinkway, T.D., et al. 2024. Crowdsourcing citizens for statewide mapping of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in Florida drinking water. Science of the Total Environment, 926: 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.171932

by Dana Stephens | Nov 17, 2025

What are PFAS?

PFAS are per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. PFAS is a class of chemicals found in various industrial and consumer goods. For instance, you may find them in food packaging, textiles, cosmetics, and frequently in aqueous film-forming foams (AFFFs) used to extinguish fires. PFAS chemicals are known for repelling grease, water, and stains, making them widely used in various applications. These chemicals are stable and persistent, earning them the nickname “forever chemicals” because they do not readily biodegrade, or break down easily in the environment.

Numerous researchers suggested PFAS are abundant in aquatic systems and toxic to a range of aquatic organisms, with additional concerns of bioaccumulation of PFAS. PFAS accumulate in sediments and aquatic organisms, which pose health risks to wildlife and humans through the food chain. Research suggests linkages of PFAS to disruption of endocrine function, reproduction, and development in aquatic organisms. Research suggests similar linkages of PFAS to humans, like increased cancer risk, immune system suppression, endocrine and reproductive disruption, and child developmental concerns.

The United States Geological Survey (USGS) estimated that at least 45% of the United States’ tap water has one or more PFAS chemicals (Smalling et al. 2023). At least one PFAS was identified in 60% of public wells and 20% of domestic wells supplying drinking water in the eastern United States (McMahon et al. 2022).

Have PFAS been found in Walton County drinking water and surface waters?

Measured PFAS in Florida and Walton County Drinking Waters

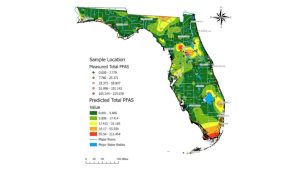

Figure 1. Map with measured total PFAS in drinking water samples across a gradient of low concentrations (green dots) to medium concentrations (yellow dots) to higher concentrations (red dots). Shaded map colors are the predicted total PFAS using estimated values of PFAS concentrations from low (green) to high (red). Data, figure, and result interpolation from Sinkway et al. 2024.

A team of researchers completed a comprehensive statewide assessment of PFAS in Florida drinking water (Sinkway et al. 2024). The team collected 448 drinking water samples across all 67 Florida counties. The drinking water samples were analyzed for 31 PFAS, where 19 PFAS were found in at least one drinking water sample. The top five most frequently detected PFAS across Florida were 6:2 fluorotelomer sulfonate (6:2 FTS) (in 84% of the samples analyzed), Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) (65%), linear perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) (65%), branched PFOS (64%), and perfluorobutane sulfonic acid (PFBS).

A total of 107 taps had PFOA or PFOS concentrations above 4 ng/L (ppt), where the maximum total PFAS concentration in a tap was 219 ng/L. A maximum contaminant level for PFOA and PFOS of 4 ng/L was implemented by the United States Environmental Protection Agency National Primary Drinking Water Regulation as of May 14, 2025 (USEPA, 2025). Overall, 8% of the drinking water samples analyzed exceeded 4 ng/L for PFOA and 16% for PFOS. The average total PFAS in city water was 15.6 ng/L, and in well water was 4.5 ng/L across Florida.

Walton County was not ranked in the 12 Florida counties with the highest maximum and average total PFAS concentrations (ng/L) in drinking water (Table 1). Walton County was not included in the rankings of Florida counties with the lowest maximum and average total PFAS concentrations (ng/L) in drinking water as the total number of samples (n=3) was below the required 5 total number sample requirement (Table 1). Among the three drinking water samples collected, the maximum PFAS concentration measured was 0 ng/L with an average of 0 ng/L. Walton County had no drinking water samples exceeding the 4 ng/L standard for PFOA.

Table 1. The 12 Florida counties with highest and lowest total PFAS drinking water concentrations (ng/L). Data, figure, and result interpolation from Sinkway et al. 2024.

Measured PFAS in Florida and Walton County Surface Waters

A team of researchers completed a comprehensive statewide assessment of PFAS in Florida surface waters (Camacho et al. 2024). A network of citizen scientists collected 2,323 surface water samples across the 67 Florida counties. These surface water samples were analyzed for 50 PFAS, with 33 PFAS being detected in at least one surface water sample across Florida. The top five most frequently detected PFAS were perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) (94% of the samples), perfluorobutane sulfonic acid (PFBS) (65%), perfluorohexanoic acid (PFHxA) (61%), perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA) (54%), and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) (53%).

There were 915 surface water samples (39%) with PFOA concentrations above 4 ng/L and 920 samples (40%) with PFOS above 4 ng/L. All counties had at least one sample with PFOA, 96% had PFNA, 93% had PFBS, 91% had PFOS, and 82% of counties had PFHxA. The average PFAS detected among counties ranged from 2 ng/L of PFNA to 10 ng/L of PFOS. The maximum PFAS detected among counties ranged from 81 ng/L of PFOA to 1135 ng/L of PFOS.

Figure 2. Surface water sampled sites with detected PFAS, where the dots’ color represents the total PFAS concentration measured. Map B shows predicted PFAS levels based on measured total PFAS concentrations in surface water samples. Note that these values do not represent predicted PFAS concentrations on land. Data, figure, and result interpolation from Camacho et al. 2024.

A total of 18 surface water samples were collected in Walton County (Figure 2). Walton County ranked 51st among Florida counties with one surface water sample (one sample out of 18 total or 5%) with PFOA above 4 ng/L. Walton County ranked 42nd for the number of samples with two samples (11%) above 4 ng/L for PFOS. The average total PFAS concentration detected in a surface water sample was 6 ng/L, while the maximum total PFAS concentration detected in a sample was 29 ng/L.

Dr. Bowden, with the University of Florida’s College of Veterinary Medicine and Chemistry Department, led the PFAS research shared here. Dr. Bowden has extensive information on the Bowden Lab website (https://www.bowdenlaboratory.com/dr-bowden.html), including an interactive map of all the PFAS surface water samples collected in Florida. Select Okaloosa County under the filter section to see the surface water samples and learn more about the PFAS information for each sample collected in Okaloosa County (https://www.bowdenlaboratory.com/florida-surface-water.html).

What does this mean for Walton County?

PFAS were not detected in drinking waters in Walton County. However, the sample size, or the number of samples, was small with three total samples collected and analyzed. PFAS were detected in surface waters in Walton County. Although not the highest concentrations or most frequent identified in Florida, there were surface water samples above USEPA’s 4 ng/L contaminant level standard for PFOA and PFOS.

Understanding what PFAS are and joining in educational conversations about PFAS helps the Walton County community. Efforts that support continued sampling and extended monitoring also increase our understanding of PFAS concentrations in Walton County’s drinking and surface waters. If you want to learn more about PFAS or join community scientists’ efforts to expand PFAS water monitoring, please contact Dana Stephens, Florida Sea Grant Extension Agent with the UF/IFAS Okaloosa County Extension Office.

References

Camacho, C.G., et al. 2024. Statewide surveillance and mapping of PFAS in Florida surface waters. American Chemical Society, 4: 434-4355. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsestwater

United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). 2025. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) final PFAS national primary drinking water regulation. https://www.epa.gov/sdwa/and-polyfluoroalkyl-substances-pfas

McMahon, P.B., Tokranov, A.K., and Bexfield, L.M. 2022. Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances in groundwater used as a source of drinking water in the Eastern United States. Environmental Science and Technology 56(4): 2279-2288. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.1c04795

Skinkway, T.D., et al. 2024. Crowdsourcing citizens for statewide mapping of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in Florida drinking water. Science of the Total Environment, 926: 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.171932

by Dana Stephens | Nov 17, 2025

What are PFAS?

PFAS are per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. PFAS is a class of chemicals found in various industrial and consumer goods. For instance, you may find them in food packaging, textiles, cosmetics, and frequently in aqueous film-forming foams (AFFFs) used to extinguish fires. PFAS chemicals are known for repelling grease, water, and stains, making them widely used in various applications. These chemicals are stable and persistent, earning them the nickname “forever chemicals” because they do not readily biodegrade, or break down easily in the environment.

Numerous researchers suggested PFAS are abundant in aquatic systems and toxic to a range of aquatic organisms, with additional concerns of bioaccumulation of PFAS. PFAS accumulate in sediments and aquatic organisms, which pose health risks to wildlife and humans through the food chain. Research suggests linkages of PFAS to disruption of endocrine function, reproduction, and development in aquatic organisms. Research suggests similar linkages of PFAS to humans, like increased cancer risk, immune system suppression, endocrine and reproductive disruption, and child developmental concerns.

The United States Geological Survey (USGS) estimated that at least 45% of the United States’ tap water has one or more PFAS chemicals (Smalling et al. 2023). At least one PFAS was identified in 60% of public wells and 20% of domestic wells supplying drinking water in the eastern United States (McMahon et al. 2022).

Have PFAS been found in Escambia County drinking water and surface waters?

Measured PFAS in Florida and Escambia County Drinking Waters

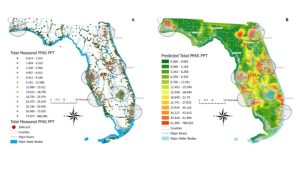

Figure 1. Map with measured total PFAS in drinking water samples across a gradient of low concentrations (green dots) to medium concentrations (yellow dots) to higher concentrations (red dots). Shaded map colors are the predicted total PFAS using estimated values of PFAS concentrations from low (green) to high (red). Data, figure, and result interpolation from Sinkway et al. 2024.

A team of researchers completed a comprehensive statewide assessment of PFAS in Florida drinking water (Sinkway et al. 2024). The team collected 448 drinking water samples across all 67 Florida counties. The drinking water samples were analyzed for 31 PFAS, where 19 PFAS were found in at least one drinking water sample. The top five most frequently detected PFAS across Florida were 6:2 fluorotelomer sulfonate (6:2 FTS) (in 84% of the samples analyzed), Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) (65%), linear perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) (65%), branched PFOS (64%), and perfluorobutane sulfonic acid (PFBS).

A total of 107 taps had PFOA or PFOS concentrations above 4 ng/L (ppt), where the maximum total PFAS concentration in a tap was 219 ng/L. A maximum contaminant level for PFOA and PFOS of 4 ng/L was implemented by the United States Environmental Protection Agency National Primary Drinking Water Regulation as of May 14, 2025 (USEPA, 2025). Overall, 8% of the drinking water samples analyzed exceeded 4 ng/L for PFOA and 16% for PFOS. The average total PFAS in city water was 15.6 ng/L, and in well water was 4.5 ng/L across Florida.

Escambia County ranked 2nd among the 67 Florida counties for the highest maximum and average total PFAS concentrations (ng/L) or the lowest maximum and average total PFAS concentrations (ng/L) in drinking water (Table 1). Among the 12 drinking water samples collected, the maximum total PFAS concentration measured was 219 ng/L, with an average total PFAS of 49 ng/L among the drinking water samples.

Table 1. The 12 Florida counties with highest and lowest total PFAS drinking water concentrations (ng/L). Data, figure, and result interpolation from Sinkway et al. 2024.

Measured PFAS in Florida and Escambia County Surface Waters

A team of researchers completed a comprehensive statewide assessment of PFAS in Florida surface waters (Camacho et al. 2024). A network of citizen scientists collected 2,323 surface water samples across the 67 Florida counties. These surface water samples were analyzed for 50 PFAS, with 33 PFAS detected in at least one surface water sample across Florida. The top five most frequently detected PFAS were perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) (94% of the samples), perfluorobutane sulfonic acid (PFBS) (65%), perfluorohexanoic acid (PFHxA) (61%), perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA) (54%), and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) (53%).

There were 915 surface water samples (39%) with PFOA concentrations above 4 ng/L and 920 samples (40%) with PFOS above 4 ng/L (Figure 2). All counties had at least one sample with PFOA, 96% had PFNA, 93% had PFBS, 91% had PFOS, and 82% of counties had PFHxA. The average PFAS detected among counties ranged from 2 ng/L of PFNA to 10 ng/L of PFOS. The maximum PFAS detected among counties ranged from 81 ng/L of PFOA to 1135 ng/L of PFOS.

Figure 2. Surface water sampled sites with detected PFAS, where the dots’ color represents the total PFAS concentration measured. Map B shows predicted PFAS levels based on measured total PFAS concentrations in surface water samples. Note that these values do not represent predicted PFAS concentrations on land. Data, figure, and result interpolation from Camacho et al. 2024.

A total of 52 surface water samples were collected in Escambia County. Escambia County ranked 22nd among Florida counties with 14 surface water samples (14 samples out of 52 total or 27%) with PFOA above 4 ng/L. Escambia County ranked 27th for the number of samples, with 7 samples (13%) above 4 ng/L for PFOS. The average total PFAS concentration detected in a surface water sample was 12 ng/L, while the maximum total PFAS concentration detected in a sample was 118 ng/L.

Dr. Bowden, with the University of Florida’s College of Veterinary Medicine and Chemistry Department, led the PFAS research shared here. Dr. Bowden has extensive information on the Bowden Lab website (https://www.bowdenlaboratory.com/dr-bowden.html), including an interactive map of all the PFAS surface water samples collected in Florida. Select Okaloosa County under the filter section to see the surface water samples and learn more about the PFAS information for each sample collected in Okaloosa County (https://www.bowdenlaboratory.com/florida-surface-water.html).

What does this mean for Escambia County?

PFAS were detected in drinking water and surface waters in Escambia County. There were drinking and surface water samples exceeding USEPA’s 4 ng/L contaminant level standard, notably in the 12 collected drinking water samples. Understanding what PFAS are and joining in educational conversations about PFAS helps our community. Efforts that support continued sampling and extended monitoring also increase our understanding of PFAS concentrations in Escambia County’s drinking and surface waters. If you want to learn more about PFAS or join community scientists’ efforts to expand PFAS water monitoring, please contact Dana Stephens, Florida Sea Grant Extension Agent with the UF/IFAS Okaloosa County Extension Office.

References

Camacho, C.G., et al. 2024. Statewide surveillance and mapping of PFAS in Florida surface waters. American Chemical Society, 4: 434-4355. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsestwater

United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). 2025. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) final PFAS national primary drinking water regulation. https://www.epa.gov/sdwa/and-polyfluoroalkyl-substances-pfas

McMahon, P.B., Tokranov, A.K., and Bexfield, L.M. 2022. Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances in groundwater used as a source of drinking water in the Eastern United States. Environmental Science and Technology 56(4): 2279-2288. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.1c04795

Skinkway, T.D., et al. 2024. Crowdsourcing citizens for statewide mapping of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in Florida drinking water. Science of the Total Environment, 926: 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.171932

by Rick O'Connor | Sep 22, 2025

Introduction

The diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin) is the only resident turtle within brackish water and estuarine systems in the United States (Fig. 1). They prefer coastal estuarine wetlands – living in salt marshes, mangroves, and seagrass communities. The literature suggests they have strong site fidelity – meaning they do not move far from where they live. Within their habitat they feed on shellfish, mollusk and crustaceans mostly. In early spring they will breed. Gravid females will venture along the shores of the bay seeking a high-dry sandy beach where they will lay a clutch of about 10 eggs. She will typically return to lay more than one clutch each season. Nesting will continue through the summer. Hatching begins mid-summer and will extend into the fall. Hatchings that occur in late fall may overwinter within the nest and emerge the following spring. They live 20-25 years.

Fig. 1. The diamondback terrapin.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

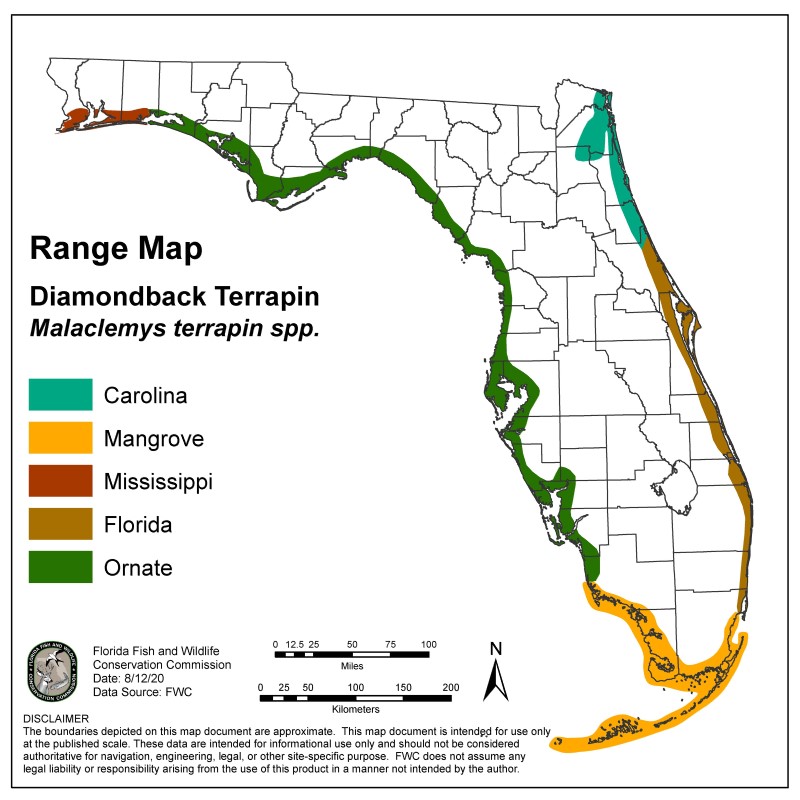

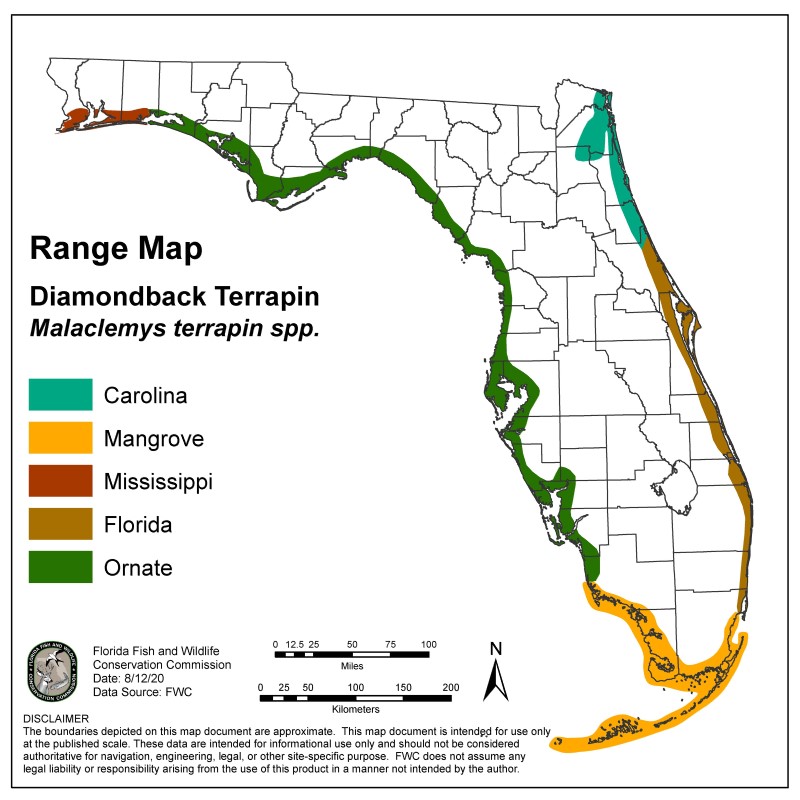

Terrapins range from Massachusetts to Texas and within this range there are currently seven subspecies recognized – five of these live in Florida, and three are only found in Florida (Fig. 2). However, prior to 2005 their existence in the Florida panhandle was undocumented. The Panhandle Terrapin Project (PTP) was initially created to determine if terrapins did exist here.

Fig. 2. Terrapins of Florida.

Image provided by FWC

The Scope of the Project

Phase 1

The project began in 2005 using trained volunteers to survey suitable habitat for presence/absence. Presence is determined by locating potential nesting beaches and searching for evidence of nesting. Nesting begins in April and ends in September – with peak nesting occurring in this area during May and June. The volunteers are trained in March and survey potential beaches from April through July. They search for tracks of nesting females, eggshells of nests that were depredated by predators, and live terrapins – either on the beach or the heads in the water. Often volunteers will conduct 30-minute head counts to determine relative abundance. Between 2005 and 2010 the team was able to verify at least one record in each of the panhandle counties.

Phase 2

The next phase is to determine their status – how many nesting beaches does each county have, and how many terrapins are using them? A suitability map was developed by Dr. Barry Bitters as a Florida Master Naturalist project to locate suitable nesting beaches. Volunteers would visit these during the spring to determine whether nesting was occurring, and the relative abundance was determined using what we called the “Mann Method” – developed by Tom Mann of the Mississippi Department of Wildlife, along with the 30-minute head counts. The Mann Method involved counting the number of tracks and depredated nests within a 16-day window. The assumption to this method was that nesting females would lay multiple clutches each season – but they did not lay more than one every 16 days. Going on another assumption, that the sex ratio within the population was 1:1, each track and depredated nest within a 16-day window was a different female and doubling this number would give the relative abundance of adults in this population. Between 2007 and 2023 we were able to determine the number of nesting beaches in each county and relative abundance in three of those counties (see results below).

Phase 3

Partnering with the U.S. Geological Survey, we were able to move to Phase 3 – which involves trapping and tagging terrapins. Doing this gives the team a better idea of where the terrapins are going and how they are using the habitat. To trap the terrapins, we use modified crab traps (modified so that the terrapins had access to air to breath), seine nets, fyke nets, dip nets, and by hand – the most effective has been modified crab traps (Fig. 3). These traps are placed in terrapin habitat over a 3-day period, being checked daily. Any captured terrapins are measured, weighed, sexed, marked using the notch method, and given a Passive Intergraded Transponder (PIT) tag. Some of the terrapins are given a satellite tag where movement could be tracked by GPS (Fig. 4). We are now bringing on acoustic tagging for some counties. This involves placing acoustic receivers on the bottom of the bay which will detect any terrapin (with an acoustic tag) that swims nearby. Results are below.

Fig. 3. Modified crab traps is one method used to capture adults.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

Fig. 4. This tag with an antenna can be detected by a satellite and tracked real time.

Photo: USGS

Phase 4

This phase involves collecting tissue samples for genetic analysis. Currently it is believed that the Ornate terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin macrospilota) ranges from Key West to Choctawhatchee Bay, and the Mississippi terrapin (M.t. pileata) ranges from Choctawhatchee Bay to the Louisiana/Texas border. The two subspecies look morphologically different (Fig. 5) and the team believes terrapins resembling the ornate terrapin have been found in Pensacola Bay. Researchers in Alabama have also reported terrapins they believe to be ornate terrapins in their waters as well. The project is now working with a graduate student from the University of West Florida who is genetically analyzing tissue samples from trapped terrapins to determine which subspecies they are and what the correct range of these subspecies. This phase began in 2025, and we do not have any results at this time.

Fig. 5. The Mississippi terrapin found in Pensacola Bay is darker in color than the Ornate terrapin found in other bays of the panhandle.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Ornate Diamondback Terrapins Depend on Coastal Marshes and Sea Grass Habitats

Photo: Erik Lovestrand.

2025 UPDATE AND RESULTS

In 2025 we trained 188 volunteers across each county – including state park rangers and members of the Florida Oyster Corps. 47 (25%) participated in at least one survey.

We logged 345 nesting surveys and 17 trap days.

No seining or fyke nets were conducted in 2025.

Phase 1 – Presence/Absence Update

| County |

Presence |

Notes |

| Baldwin |

Yes |

A single deceased terrapin was found in western Baldwin County |

| Escambia |

Yes |

Team encountered nesting again this year |

| Santa Rosa |

Yes |

Two new locations were identified this year |

| Okaloosa |

Yes |

Encounters were lower this year |

| Walton |

Yes |

FIRST EVIDENCE OF NESTING IN WALTON COUNTY VERIFIED THIS YEAR |

| Bay |

Yes |

FIRST EVIDENCE OF NESTING IN BAY COUNTY VERIFIED THIS YEAR |

| Gulf |

Yes |

Team encountered nesting again this year |

| Franklin |

ND |

ND |

Phase 2 Nesting Survey – Update

| County |

# of primary beaches1 |

# of secondary beaches2 |

# of surveys |

# of encounters |

FOE3 |

| Baldwin |

0 |

TBD |

14 |

04 |

.00 |

| Escambia |

2 |

35 |

99 |

7 |

.07 |

| Santa Rosa |

3 |

45 |

137 |

25 |

.18 |

| Okaloosa |

4 |

3 |

20 |

1 |

.05 |

| Walton |

1 |

4 |

28 |

2 |

.07 |

| Bay |

3 |

3 |

47 |

14 |

.30 |

| TOTAL |

13 |

17 |

345 |

49 |

.14 |

1 primary beaches are defined as those where nesting is known to occur.

2 secondary beaches are defined as those where potential nesting is high but has not been confirmed.

3 FOE (Frequency of Encounters) is the number of terrapin encounters / the number of surveys conducted.

4 There was one deceased terrapin found by a tour guide in Baldwin County but was not part of the project.

5 There are potential nesting sites on Pensacola Beach that are technically in Escambia County but covered by the Santa Rosa team. The Escambia team focused on the Perdido Key area.

Phase 3 Trapping/Tagging Update

We currently have 8 years of data.

Terrapins have been tagged in 7 of the 8 panhandle counties.

1483 captures, 1061 individuals.

2025 Capture Effort

| Method |

County |

Number |

Description |

Condition |

| Hand capture |

Escambia |

1 |

1 adult male |

Deceased |

| Hand capture |

Santa Rosa |

5 |

4 adult females

1 unknown |

Released, deceased |

| Hand capture |

Okaloosa |

1 |

1 adult female |

Released |

| Dip Net |

Santa Rosa |

1 |

1 adult male |

Released |

| Crab Traps |

Santa Rosa |

34 |

4 juvenile females

5 adult females

25 adult males |

Released |

|

Okaloosa |

4 |

1 juvenile female

3 adult males |

Released |

| TOTAL |

|

46 |

5 juvenile females

10 adult females

30 adult males

1 unknown |

|

Preliminary information subject to revision. Not for citation or distribution.

Satellite Tagging Information

Due to the size of the tags – only large females are satellite tagged at this time.

Big Momma – tracked for 188 days – averaged 0.16 miles.

Big Bertha – tracked for 137 days – averaged 35.83 miles.

2025 Tracking Effort

| County |

Tagging Effort |

| Santa Rosa |

2 satellite tagged

6 acoustically tagged |

| Okaloosa |

1 satellite tagged |

| TOTAL |

8 tagged for tracking |

Phase 4 Update

This phase began in 2025 and there are no results at this time.

Summary

2025

17 trainings were given in 7 of the 8 counties of the Florida panhandle (including Baldwin County AL).

188 were trained; 47 (25%) conducted at least one survey.

345 surveys were logged; terrapins (or terrapin sign) were encountered 49 (14%) of those surveys.

Every county had at least one encounter during a nesting survey.

17 trapping days were conducted; 46 terrapins were captured; 37 (83%) were captured in modified crab traps; 7 were captured by hand; 1 was captured in a dip net.

8 terrapins were tagged for tracking; 6 acoustically; 2 with satellite tags.

Since 2007

511 have been trained.

1449 surveys have been logged; 347 encounters have occurred; Frequency of Encounters is 24% of the surveys.

Discussion

Phase 1

We have shown that diamondback terrapins do exist in the Florida panhandle and in Baldwin County AL.

Phase 2

We currently have 13 primary nesting beaches we are surveying weekly during nesting season across the panhandle. There were 17 secondary nesting beaches surveyed and most likely there are many more to visit. Nesting seems to be more common in late spring, but the Frequency of Encounters has been declining since 2023. This could be due to less terrapin activity but could also be due to evidence being difficult to find. We will continue to monitor to see how this trend continues.

Phase 3

The team has captured 1483 terrapins, the majority of which were from the eastern panhandle. Satellite tagged females suggest more than one has traveled over 30 miles from where they were tagged. This goes against the idea that terrapins have strong site fidelity. However, all the terrapins tagged were large females (due to size of the tags) so we are looking at the movements of only the larger females – not the population as a whole. The movements of these females also suggest they may use seagrass beds as much as the salt marshes.

Training for volunteers occurs in March of each year. If you are interested in participating, contact Rick O’Connor – roc1@ufl.edu.

by Dana Stephens | Jul 7, 2025

PFAS—have you heard of them? Do you know what they are, or is it more of a term thrown around without much context?

PFAS are per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. PFAS is a class of chemicals found in various industrial and consumer goods. For instance, you may find them in food packaging, textiles, cosmetics, and frequently in aqueous film-forming foams (AFFFs) used to extinguish fires. PFAS chemicals are known for repelling grease, water, and stains, making them widely used in various applications. These chemicals are stable and persistent, earning them the nickname “forever chemicals” because they do not readily biodegrade, or break down easily in the environment.

Numerous researchers suggested PFAS are abundant in aquatic systems and toxic to a range of aquatic organisms, with additional concerns of bioaccumulation of PFAS. PFAS accumulate in sediments and aquatic organisms, which pose health risks to wildlife and humans through the food chain. Research suggests linkages of PFAS to disruption of endocrine function, reproduction, and development in aquatic organisms. Research suggests similar linkages of PFAS to humans, like increased cancer risk, immune system suppression, endocrine and reproductive disruption, and child developmental concerns.

The United States Geological Survey (USGS) estimated at least 45% of the United States’ tap water has one or more PFAS chemicals (Smalling et al. 2023). At least one PFAS was identified in 60% of public wells and 20% of domestic wells supplying drinking water in the eastern United States (McMahon et al. 2022).

Have PFAS been found in Okaloosa County drinking water and surface waters?

Measured PFAS in Florida and Okaloosa County Drinking Waters

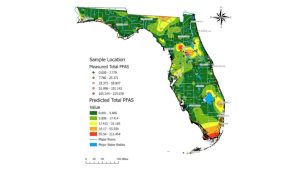

Figure 1. Map with measured total PFAS samples across a gradient of low concentrations (green dots) to medium concentrations (yellow dots) to higher concentrations (red dots). Shaded map colors are the predicted total PFAS using estimated values of PFAS concentrations from low (green) to high (red). Data, figure, and result interpolation from Sinkway et al. 2024.

A team of researchers completed a comprehensive statewide assessment of PFAS in Florida drinking water (Sinkway et al. 2024). The team collected 448 drinking water samples across all 67 Florida counties. The drinking water samples were analyzed for 31 PFAS, where 19 PFAS were found in at least one drinking water sample. The top five most frequently detected PFAS were 6:2 fluorotelomer sulfonate (6:2 FTS) (in 84% of the samples analyzed), Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) (65%), linear perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) (65%), branched PFOS (64%), and perfluorobutane sulfonic acid (PFBS).

A total of 107 taps had PFOA or PFOS concentrations above 4 ng/L (ppt), where the maximum total PFAS concentration in a tap was 219 ng/L (Click on link for higher resolution–Figure 1). The maximum contaminant level for PFOA and PFOS is 4 ng/L, legally enforced by the United States Environmental Protection Agency National Primary Drinking Water Regulation as of May 14, 2025 (USEPA, 2025). Overall, 8% of the drinking water samples analyzed exceeded 4 ng/L for PFOA and 16% for PFOS. The average total PFAS in city water was 15.6 ng/L, and in well water was 4.5 ng/L.

Table 1. Top average 12 Florida counties with highest and lowest total PFAS concentrations (ng/L). Data, figure, and result interpolation from Sinkway et al. 2024.

Okaloosa County had the 11th highest total PFAS (ng/L) concentration among the 67 Florida counties (Click on link for higher resolution–Table 1). Among the eight drinking water samples collected, the maximum PFAS concentration measured was 140 ng/L, and the lowest was 18 mg/L. Okaloosa County had one drinking water sample that exceeded the 4 ng/L standard for PFOA. There were no drinking water samples that exceeded 4 ng/L for PFOS.

Measured PFAS in Florida and Okaloosa County Surface Waters

A team of researchers completed a comprehensive statewide assessment of PFAS in Florida surface waters (Camacho et al. 2024). A network of citizen scientists collected 2,323 surface water samples across the 67 Florida counties. These surface water samples were analyzed for 50 PFAS, with 33 PFAS being detected in at least one surface water sample. The top five most frequently detected PFAS were perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) (94% of the samples), perfluorobutane sulfonic acid (PFBS) (65%), perfluorohexanoic acid (PFHxA) (61%), perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA) (54%), and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) (53%).

Figure 2. Map A contains all surface water sampled sites with detected PFAS, where the dots’ color represents the total PFAS concentration measured. Map B shows predicted PFAS levels based on measured total PFAS concentrations in surface water samples. Note that these values do not represent predicted PFAS concentrations on land. Data, figure, and result interpolation from Camacho et al. 2024.

There were 915 (39%) surface water samples with PFOA concentrations above 4 ng/L and 920 (40%) samples with PFOS above 4 ng/L (Click on link for higher resolution–Figure 2). All counties had at least one sample with PFOA, 96% had PFNA, 93% had PFBS, 91% had PFOS, and 82% of counties had PFHxA. The average PFAS detected among counties ranged from 2 ng/L of PFNA to 10 ng/L of PFOS. The maximum PFAS detected among counties ranged from 81 ng/L of PFOA to 1135 ng/L of PFOS. Figure 2

Okaloosa County ranked 27th among Florida counties due to 10 (20%) surface water samples with PFOA above 4 ng/L. Okaloosa County ranked 9th for the number of samples (38 total samples or 78% of the samples) above 4 ng/L for PFOS. A total of 49 surface water samples were collected in Okaloosa County. The average total PFAS concentration detected in a surface water sample was 31 ng/L, while the maximum total PFAS concentration detected in a sample was 185 ng/L.

Dr. Bowden, with the University of Florida’s College of Veterinary Medicine and Chemistry Department, led the PFAS research shared here. Dr. Bowden has extensive information on the Bowden Lab website (https://www.bowdenlaboratory.com/dr-bowden.html), including an interactive map of all the PFAS surface water samples collected in Florida. Select Okaloosa County under the filter section to see the surface water samples and learn more about the PFAS information for each sample collected in Okaloosa County (https://www.bowdenlaboratory.com/florida-surface-water.html).Figure 2 Table 1

What does this mean for Okaloosa County?

PFAS have been detected in drinking water and surface waters in Okaloosa County. Although not the highest concentrations or most frequent identified in Florida, there were drinking and surface water samples above USEPA’s 4 ng/L contaminant level standard. Understanding what PFAS are and joining in educational conversations about PFAS helps our community. Efforts that support continued sampling and extended monitoring also increase our understanding of PFAS concentrations in Okaloosa County’s drinking and surface waters. If you want to learn more about PFAS or join community scientists’ efforts to expand PFAS water monitoring, please contact Dana Stephens at the UF/IFAS Okaloosa County Extension Office.

References

Camacho, C.G., et al. 2024. Statewide surveillance and mapping of PFAS in Florida surface waters. American Chemical Society, 4: 434-4355. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsestwater

United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). 2025. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) final PFAS national primary drinking water regulation. https://www.epa.gov/sdwa/and-polyfluoroalkyl-substances-pfas

McMahon, P.B., Tokranov, A.K., and Bexfield, L.M. 2022. Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances in groundwater used as a source of drinking water in the Eastern United States. Environmental Science and Technology 56(4): 2279-2288. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.1c04795

Skinkway, T.D., et al. 2024. Crowdsourcing citizens for statewide mapping of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in Florida drinking water. Science of the Total Environment, 926: 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.171932