by Andrea Albertin | Jan 28, 2021

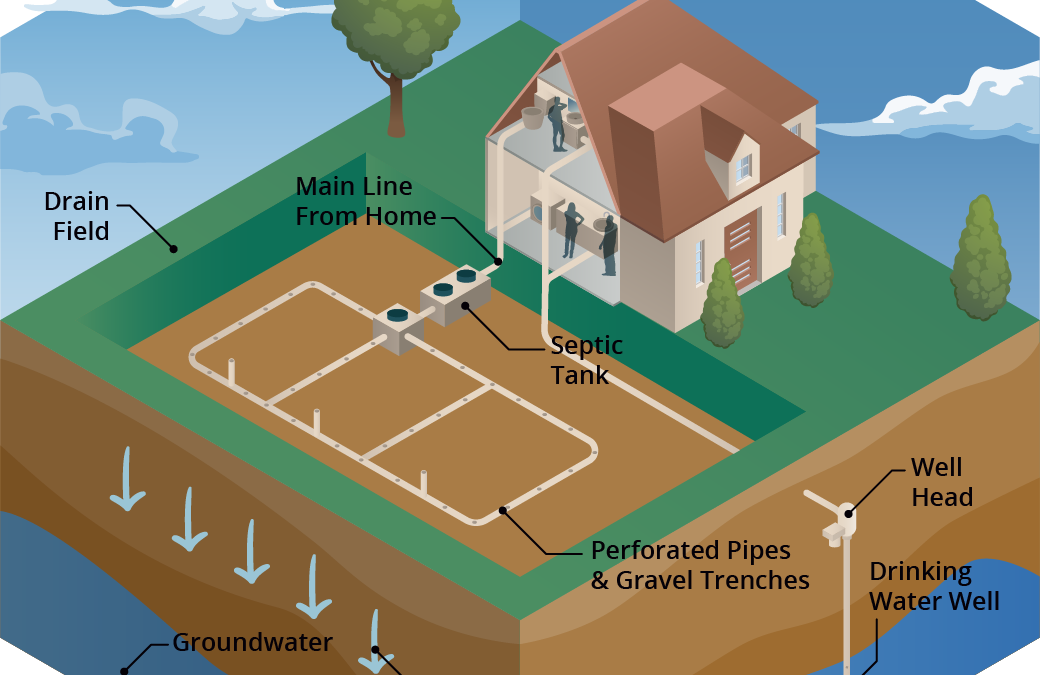

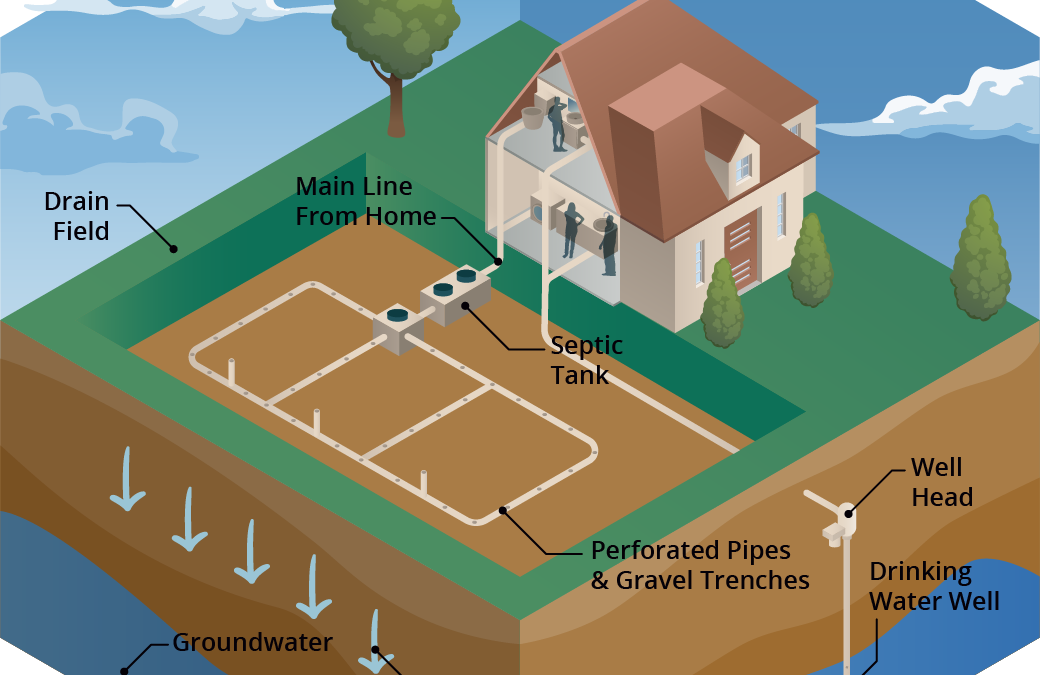

Senate Bill 712 ‘The Clean Waterways Act’ was signed into Florida law on June 30, 2020. The purpose of the bill is to better protect Florida’s water resources and focuses on minimizing the impact of known sources of nutrient pollution. These sources include septic systems, wastewater treatment plants, stormwater runoff as well as fertilizer used in agricultural production.

Senate Bill 712 focuses on protecting Florida’s water resources such as Jackson Blue Springs/Merritt’s Mill Pond, pictured here. Credit: Doug Mayo, UF/IFAS.

What major provisions are included in SB 712?

Primary actions required by SB712 were listed in a news release by Governor Desantis’ staff in June 2020 as:

- Regulation of septic systems as a source of nutrients and transfer of oversight from the Florida Department of Health (DOH) to the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (DEP).

- Contingency plans for power outages to minimize discharges of untreated wastewater for all sewage disposal facilities.

- Provision of financial records from all sanitary sewage disposal facilities so that DEP can ensure funds are being allocated to infrastructure upgrades, repairs, and maintenance that prevent systems from falling into states of disrepair.

- Detailed documentation of fertilizer use by agricultural operations to ensure compliance with Best Management Practices (BMPs) and aid in evaluation of their effectiveness.

- Updated stormwater rules and design criteria to improve the performance of stormwater systems statewide to specifically address nutrients.

How does the bill impact septic system regulation?

The transfer of the Onsite Sewage Program (OSP) (commonly known as the septic system program) from DOH to DEP becomes effective on July 1, 2021. So far, DOH and DEP submitted a report to the Governor and Legislature at the end of 2020 with recommendations on how this transfer should take place. They recommend that county DOH employees working in the OSP continue implementing the program as DOH-employees, but that the onsite sewage program office in the State Health Office transfer to DEP and continue working from there. DOH created an OSP Transfer web page where updates and documents related to the transfer are posted.

How does the bill impact agricultural operations?

SB 712 affects all landowners and producers enrolled in the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services (FDACS) BMP Program. Under this bill:

- Every two years FDACS will make an onsite implementation verification (IV) visit to land enrolled in the BMP program to ensure that BMPs are properly implemented. These visits will be coordinated between the producer and field staff from FDACS Office of Agriculture and Water Policy (OAWP).

- During these visits (and as they have done in the past), field staff will review records that producers are required to keep under the BMP program.

- Field staff will also collect information on nitrogen and phosphorus application. FDACS has created a specific form, the Nutrient Application Record Keeping Form or NARF where producers will record quantities of N and P applied. FDACS field staff will retain a copy of the NARF during the IV visit.

FDACS-OAWP prepared a thorough document with responses to SB 712 Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ’s). It includes responses to questions about site visits, the NARF and record keeping, why FDACS is collecting nutrient records and what will be done with this information. The fertilizer records collected are not public information, and are protected under the public records exemption (Section 403.067 Florida Statutes). For areas that fall under a Basin Management Action Plan (like the Jackson Blue and Wakulla Springs Basins in the Florida Panhandle), FDACS will combine the nitrogen and phosphorus application data from all enrolled properties (total pounds of N and P applied within the BMAP). It will then send the aggregated nutrient application information to FDEP.

Details of how all aspects of SB 712 will be implemented are still being worked out and we should continue to hear more in the coming months.

by Rick O'Connor | Jan 8, 2021

It’s winter…

The sky is clear, the humidity is low, the bugs are gone, and the highs are in the 60s – most days. These are perfect days to get outside and enjoy. But the water is cold and you do not want to get wet – most days. And with COVID hanging around we do not want to go where there are crowds. Where can I go to enjoy this great weather, the outdoors, but stay safe?

As the summer heat fades, the weather is great for hiking! Photo credit: Abbie Seales

Hiking…

My wife and I have already made several hikes this winter and have enjoyed each one. Each panhandle county has several hiking trails you could visit. In our county there are city, county, state, and federal trails to choose from. The Florida Trail begins in Escambia County, at Ft. Pickens on Santa Rosa Island, and dissects each county in the panhandle on its way to the Everglades. You could find the section running through yours and hike that for a day. Community parks, our local university, state and national parks, and the water management district, all have trails.

Some are a short loops and easy. Others can be 20 plus miles, but you do not have to hike it all. Go for as long as you like and then return to the car. Some are handicapped access, some have paved sections, or boardwalks. Some go along waterways and the water is so clear in the winter that you can see to the bottom. Many meander through both open areas and areas with a closed tree canopies.

The tracks of the very common armadillo.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

The boardwalk of Deer Lake State Park off of Highway 30-A. you can see the tracks of several types of mammals who pass under at night.

Being winter, the wildlife viewing may be less. The “warm bloods” are moving – birds and mammals. Actually, the birds are everywhere, it is a great time to go birding if you like that. Mammals are still more active at dawn dusk, but their tracks are everywhere. We have seen raccoon, coyote, and deer on many of our hikes. But the insects are down as well. We have not had a yellow fly or mosquito gives us a problem yet. Some fear snakes, we actually like the see them, but we have not. Many will come out of their dens when the days warm and the sun is out to bask for a bit before retreating back into their lair. You might feel more comfortable hiking knowing the chance of an encounter one this time of year is much less.

One of the many Florida State Forest trails in South Walton.

The Florida Trail extends (in sections) over 1,300 miles from Ft. Pickens to the Florida Everglades. It begins at this point.

But the views are great and the photography excellent. Some mornings we have had fog issues, but it quickly lifts, and the bay is often slick as glass with pelicans, loons, and cormorants paddling around. These have made for some great photos.

Things to consider for your hike.

Good shoes. Many of the trails we have hiked have had wet and muddy sections.

Temperature. There can be big swings when going from open sunny areas to under the tree canopies. Wear clothes in layers and have a backpack that can hold what you want to take off. Some like to wear the fleece vests so they do not have to put on/remove as they hike.

Water. I bring at least 32 ounces. It is not hot, but water is still needed.

Snacks. Always a plus. I always miss them when I do not have them.

Camera. Again, the scenery and the birds are really good right now.

The best thing is that you are getting outside, getting exercise, and getting away from the crazy world that is going on right now. Take a “mind break” and take a hike.

Here are some hikes suggested by hiking guides.

Gulf Islands National Seashore / Ft. Pickens – Florida Trail (Ft. Pickens section) – 2 miles – Pensacola Beach

Blackwater State Forest – Jackson Red Ground Trail – 21 miles – near Munson FL

Falling Waters State Park – Falls, Sinkhole, and Wiregrass Trail – ~ 1 mile – near Chipley on I-10

Grayton Beach State Park – Dune Forest Trail – < 1 mile – 30-A in Walton County

T.H. Stone Memorial St. Joseph Peninsula State Park – Beach Walk and Wilderness Preserve Trail – ~ 9 miles – near Port St. Joe FL

Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravine Preserve – Garden of Eden Trail – 4 mile loop – Hwy 12 near Bristol FL

Torreya State Park – Torreya River Bluff Loop Trail – 7 mile loop – Hwy 271 near Bristol

Leon Sinks Geological Area – Sinkhole and Gumswamp Trail – 3 mile loop – US 319 near Tallahassee

Edward Ball Wakulla Springs State Park – Sally Ward Springs and Hammock Trails – 2.5 miles out and back – Hwy 20 near Wakulla FL

St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge – Stoney Bayou Trail – ~ 6 miles – CR 59 near Gulf of Mexico

by Rick O'Connor | Dec 3, 2020

Along the northern Gulf coast is a string of long-thin sand bar islands we call barrier islands. They are called this because they serve as a barrier to the mainland from open water storms. These long sandy islands are very dynamic and constantly shift and move with the tides, currents, and waves. They can shift as far as 300 feet after a strong hurricane.

The white quartz sand beaches of the barrier island in the northern Gulf of Mexico.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

Life on these islands can be very tough. In addition to the constantly moving sand, there is salt spray in the wind, intense sunlight much of the year, high winds at times, and little rainfall to provide freshwater. Even though our area can receive as much as 60 inches of rain a year, much of this falls in the northern end of the counties, and not on the beaches. That said, there are freshwater ponds on some the islands and even larger dune lakes in Walton County – there life is not as hard.

As you cross a barrier island from the Gulf to the bay, you will cross distinct environmental zones. These zones are defined by the abiotic factors wind and salt spray and are named by their dominant plant forms having distinct animal life associated with them.

The beach zone seems life-less but it is not. Look beneath the sand.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

The beach is barren. This is the section of sand that extends from the water line of the Gulf to the first line of dunes. Few, if any plants can grow here. The high wave energy will not allow plants to grow along the shoreline, nor in the water itself. The wind and salt spray are high and the sand ever changing. All of the animal life here lives beneath the sand. They emerge when the wind and waves have slowed and scavenge on what they can find for food. Their primary production comes from the decomposition of the strands of seagrass and seaweed that line the shore – what we call wrack. Many will filter phytoplankton from the water as the waves wash in and seabirds are constant predators. When conditions get a little too much, they migrate a little offshore in deeper water to wait it out. But here fish and larger invertebrates become predators – so, they may not stay long.

The primary dune is dominated by salt tolerant grasses like this sea oat.

Inland of the beach is the first dune line – the primary dune. This dune field is dominated by grasses because woody plants cannot tolerate the high wind. Most of these herbaceous plants have fibrous root systems that trap blowing sand and form dunes. The dominant grasses found here would include panic grass, beach elder, and the sea oat. The seeds of these plants provide food for creatures like the beach mice and some birds. Ghost crab burrows are often found here seeking shelter from the high energy environment of the beach. And, as you would expect, predators visit. Snakes, coyotes, and fox seeking the small mice.

Small round shrubs and brown grasses within the swales are characteristic of the secondary dune field.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

This primary dune line blocks some of the wind and salt spray from the Gulf and allows small woody shrubs to grow. These shrubs will form a secondary dune system, which may grow slightly higher than the primary dunes. Shrubs like seaside rosemary, goldenrod, and false rosemary can be found here and give the dunes color when they are in bloom. The grasses found in the primary dune can also be found here. Beach mice and ghost crabs can work their way to this environment but because the wind is blocked by the primary dune other animals can be found here including: armadillos, opossum, a variety of snakes, and maybe even a gopher tortoise. Within the secondary dune field there are low areas that, at times, fill with rainwater. These are called swales and have their own unique wildlife. Grasses like broomsedge, needlerush, and bull rush can be found here. Along the edge you may find carnivorous plants such as the sundew. Freshwater attracts all wildlife, but the tenants could include a variety of amphibians, reptiles, and even some hardy species of fish.

The top of a pine tree within a tertiary dune.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

On the back side of the island are some of the largest dunes. These are held in place by salt tolerant trees such as live oak, pine, and even magnolia. However, these trees look different than the ones that grow in our yards. They are the same species, but their growth seems stunted and often they look like the wind has blown their growth northward. This is known as wind sculpting and all of it is caused by the salt spray coming from the Gulf. These trees form a maritime forest where a variety of wildlife species do well. Deer, armadillo, opossum, skunks, coyote, fox, raccoon, hawks, owls, eagles, all sorts of snakes and woodland birds can be found here. In these xeric conditions, it is not uncommon to find a lot of cactus. Most of these creatures are hiding during the day, but at sunset they begin to move.

During these colder winter months, we encourage you to explore these beach habitats.

by Daniel J. Leonard | Sep 3, 2020

Overcup on the edge of a wet weather pond in Calhoun County. Photo courtesy of Daniel Leonard.

Haunting alluvial river bottoms and creek beds across the Deep South, is a highly unusual oak species, Overcup Oak (Quercus lyrata). Unlike nearly any other oak, and most sane people, Overcups occur deep in alluvial swamps and spend most of their lives with their feet wet. Though the species hides out along water’s edge in secluded swamps, it has nevertheless been discovered by the horticultural industry and is becoming one of the favorite species of landscape designers and nurserymen around the South. The reasons for Overcup’s rise are numerous, let’s dive into them.

The same Overcup Oak thriving under inundation conditions 2 weeks after a heavy rain. Photo courtesy Daniel Leonard.

First, much of the deep South, especially in the Coastal Plain, is dominated by poorly drained flatwoods soils cut through by river systems and dotted with cypress and blackgum ponds. These conditions call for landscape plants that can handle hot, humid air, excess rainfall, and even periodic inundation (standing water). It stands to reason our best tree options for these areas, Sycamore, Bald Cypress, Red Maple, and others, occur naturally in swamps that mimic these conditions. Overcup Oak is one of these hardy species. It goes above and beyond being able to handle a squishy lawn, and is often found inundated for weeks at a time by more than 20’ of water during the spring floods our river systems experience. The species has even developed an interested adaptation to allow populations to thrive in flooded seasons. Their acorns, preferred food of many waterfowl, are almost totally covered by a buoyant acorn cap, allowing seeds to float downstream until they hit dry land, thus ensuring the species survives and spreads. While it will not survive perpetual inundation like Cypress and Blackgum, if you have a periodically damp area in your lawn where other species struggle, Overcup will shine.

Overcup Oak leaves in August. Note the characteristic “lyre” shape. Photo courtesy Daniel Leonard.

Overcup Oak is also an exceedingly attractive tree. In youth, the species is extremely uniform, with a straight, stout trunk and rounded “lollipop” canopy. This regular habit is maintained into adulthood, where it becomes a stately tree with a distinctly upturned branching habit, lending itself well to mowers and other traffic underneath without having to worry about hitting low-hanging branches. The large, lustrous green leaves are lyre-shaped if you use your imagination (hence the name, Quercus lyrata) and turn a not-unattractive yellowish brown in fall. Overcups especially shine in the winter when the whitish gray shaggy bark takes center stage. The bark is very reminiscent of White Oak or Shagbark Hickory and is exceedingly pretty relative to other landscape trees that can be successfully grown here.

Finally, Overcup Oak is among the easiest to grow landscape trees. We have already discussed its ability to tolerate wet soils and our blazing heat and humidity, but Overcups can also tolerate periodic drought, partial shade, and nearly any soil pH. They are long-lived trees and have no known serious pest or disease problems. They transplant easily from standard nursery containers or dug from a field (if it’s a larger specimen), making establishment in the landscape an easy task. In the establishment phase, defined as the first year or two after transplanting, young transplanted Overcups require only a weekly rain or irrigation event of around 1” (wetter areas may not require any supplemental irrigation) and bi-annual applications of a general purpose fertilizer, 10-10-10 or similar. After that, they are generally on their own without any help!

Typical shaggy bark on 7 year old Overcup Oak. Photo courtesy Daniel Leonard.

If you’ve been looking for an attractive, low-maintenance tree for a pond bank or just generally wet area in your lawn or property, Overcup Oak might be your answer. For more information on Overcup Oak, other landscape trees and native plants, give your local UF/IFAS County Extension office a call!

by Erik Lovestrand | Jun 21, 2019

Mississippi kites are smaller but impressive aerialists as well. Photo by Andy Reago, Flickr Creative Commons.

Dime store kites were never very expensive, but it still seemed like a luxury when I was growing up and it was a rare thing for us kids to see a store-bought kite flying over our neighborhood. An old paper grocery bag (remember those), some cotton string for the corner loops, and two dog fennel sticks cut from the back field provided the basic ingredients for us to make our own. With a little creative cutting and gluing, and the attachment of a tail made from torn strips from a worn-out shirt, it was a thing of grace and beauty and was soon aloft on the wind. On a good day, with the right breeze (not too light, not too gusty), we could run out two full rolls of kite string until the kite was just a speck in the distance. The real challenge was winding all of that string back in after the kite came down across houses, powerlines and fields.

Please forgive the digression but thinking about the topic for this article sent me on a little trip down memory lane. We are fortunate to have two very interesting avian species of kites that grace our summer skies over North Florida. Both are exceptional aerialists but one of them in particular will leave a visual image that is hard to shake. The swallow-tailed kite (Elanoides forficatus) is one of the most impressive birds on the planet with its stark white belly and under-wing coverts, outlined in bold black trim. Its deeply forked tail gives rise to several descriptive names such as split-tailed hawk and fork-tailed hawk, among others. Each spring, swallow-tailed kites migrate in small groups back to their breeding range that extends into the Florida Peninsula and sections of the Panhandle, including several North Florida counties. I’ve seen up to 21 kites flying over the Apalachicola River floodplain during this time of year. Forested swamp habitats along river corridors are particularly valuable for foraging and nesting areas but these graceful flyers are also observed over agricultural fields and pastures where they catch dragonflies and other bugs on the wing; usually dining in the air. Nesting takes place in treetops and young are fed a mixed bag of insects, tree frogs, lizards and small snakes, most snatched from the treetops in flight. Occasionally, the young of other birds are taken from their nests and added to the menu. After the young have fledged from the nest, it isn’t long before our kites head back to their wintering grounds in South America. Young birds can be identified by their less-deeply forked tail, due to the short outer tail feathers.

The other kite that graces our area during summertime is the Mississippi kite (Ictinia mississippiensis); not quite as flashy as its fork-tailed cousin but beautiful in its own right. Adult Mississippi kites are a pearly gray color with darker wings and tail. They are significantly smaller, with a wingspan of about 3 feet (swallow-tailed kites have a wingspan up to 4.5 feet). Wintering grounds are in South America also but the breeding range in the US includes several western states such as Texas, Oklahoma and even sparsely in New Mexico and Arizona. This species is known to vigorously defend its nest by dive-bombing trespassers who get too close.

I see both species flying around my house in Wakulla County and without fail, I pause to appreciate the grace, beauty and tremendous distances covered during annual flights by these long-distance migrants. Keep looking up during our summer months and you may well be rewarded by a glimpse of these two “kites over North Florida.”