by Laura Tiu | Nov 19, 2021

There are a lot of good oyster quotes. One I remember from childhood is the saying to only eat oysters in months with the letter “r,” basically September to April. I believe this originated when all oysters came from the wild. This was a way to avoid the hot months that may have led to a watery oyster, or even food poisoning. Today, with the rise of oyster aquaculture and refrigeration, oysters can be enjoyed year-round.

The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission recently made the tough decision to shut down wild oyster harvesting in Apalachicola, FL for up to five years in response to a struggling bay oyster population threatened by water flow issues and overharvesting. This was devastating news to an area that historically produced 90% of the state’s oysters and 10% of the nation’s. On the bright side, oyster aquaculture has been steadily growing in the area and is working hard to fill some of the gap.

A team of Florida Sea Grant Agents recently made a visit to Apalachicola to learn more about this historic oyster town and how the industry is adapting. Our first stop was Water Street Seafood, the Florida Panhandle’s largest seafood distributer. Water Street provides a wide diversity of both fresh and frozen seafood, including oysters, delivering daily in northwest Florida and shipping worldwide. We visited their oyster processing facility where we saw mesh bags of oysters brought in from Louisiana and Texas. The oysters, both farmed and wild caught, are carefully cleaned and sorted, with some going to the live, halfshell, restaurant market and some shucked onsite for the shucked market.

Next, we visited one of the many new oyster aquaculture farms in the area. Oysters farms are permitted by the state and are located in waters that have been carefully evaluated for their suitability for oyster production. Small plots are leased to the farmer allowing off-bottom production in mesh bags teathered with anchors in the shallow, productive bay waters. Oyster farmers tend to their crop by turning the bags regularly to reduce fouling of the oyster shell, and sorting by size as the oyster grows. Oysters take between eight to eighteen months to reach a harvest size.

Given the increasing demand for oysters by tourists and locals, we can thank aquaculture for keeping these tasty gems on our plates. If you are lucky enough to find some locally raised oysters on the menu, take the opportunity to try something new and support a local farmer.

An oyster farmer visiting his lease to monitor his crop. (credit: L. Tiu)

T

Fresh live oysters from an Apalachicola Oyster Farm (credit: L. Tiu)

Oyster bag holding cooler at Water Street Seafood with green bags holding wild caught oysters and purple bags holding farm raised oysters. (credit: L. Tiu)

by Rick O'Connor | Nov 4, 2021

In this series we have looked at where the concept of climate change came from and how climate has changed over the centuries. We looked closer at the changes over the last decade and what the most recent IPCC report is telling us. We also looked at how changes have impacted Florida and the panhandle specifically. Much of the news is concerning to many and the outlook for the rest of the century paints a picture of climate problems we will have to deal with. But hope is not lost. Based on the 2021 AR6 report, even if we stop all greenhouse gas emissions today, the sea will rise – we have missed that tipping point and will have to plan for that. But there are other areas where our communities can make changes to help turn this thing around. In Part 5 we will look at potential solutions and specifically focus on where individuals like you and I can make changes that can help.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

Where do you start?

As G.T. Miller states in his book Living in the Environment1 it is going to be tough. It is a global problem and will take many nations to agree to make things happen. We know how hard that can be. It is also a political problem, and we know that can be hard as well. It is also affecting some regions of the planet more than others and thus some will be more concerned and ready to act, while others do not see the need to spend resources on the issue. Miller states there are two basic plans of attack on this – (1) reduce greenhouse gas emissions, or (2) try and mitigate the impacts.

During the 1970s Dr. William Rathje developed a program at the University of Arizona called Garbology. One of the objectives of the program was to determine what humans throw away in order to determine what the “big players” were in reducing solid waste going to the landfill1. They were able to develop a pie chart showing what items made up the material we call garbage and then developed a plan to reduce those “big players”. Let’s take the same approach with reducing greenhouse gases. What are the sources of these gases? Who are the “big players” so that we know where to direct our efforts to significantly reduce emissions and curtail some of the possible problems predicted by the models?

According to a 2021 EPA report, carbon dioxide (CO2) makes up 76% of the global greenhouse gas emissions2. This would be an obvious gas to target significant reductions. 86% of the carbon dioxide comes from the burning of fossil fuels, a more specific target for reduction and a good starting point.

| Percentage of Greenhouse Gas Emissions |

Gas |

Source |

| 65% |

Carbon dioxide (CO2) |

Fossil Fuels |

| 16% |

Methane (CH4) |

Waste, Biomass energy |

| 11% |

Carbon dioxide (CO2) |

Deforestation, Agriculture, and Soil degradation |

| 6% |

Nitrous oxide (N2O) |

Fertilizer use |

| 2% |

Fluorinated gases |

Industrial processing, Refrigerators, and some consumer products |

Source: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

So, where are fossil fuels being burned?

Where can we begin to discuss reductions there?

The same US EPA report breaks down the economic sectors where greenhouse gases are being produced on a global scale. A second report focuses on those same sectors but from the United States3. The table below compares these two.

| Global Economic Sector |

Percent |

U.S. Economic Sector |

Percent |

| Electricity and Heat Production |

25% |

Transportation |

29% |

| Agriculture and Forestry activities |

24% |

Electricity and Heat Production |

25% |

| Industry |

21% |

Industry |

23% |

| Transportation |

14% |

Commercial and Residential use |

13% |

| Other Energy Sources |

10% |

Land Use and Forestry activities |

12%1 |

|

|

Agriculture |

10% |

Source: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

noted that total my not round to 100% due to independent rounding

Comparing the greenhouse gas emissions of U.S. economic sectors to those of the world shows a few things.

- Electricity and heat production is a major producer of GHG and a good target for reduction.

- Transportation is a larger problem in the U.S., in fact it is the number one problem.

- Agriculture and forestry are larger problems on the global scale, less of one in the U.S.

- Commercial and residential use is a larger problem than agriculture and forestry in the U.S., it was not even reported on a global scale.

Now we know who the “big players” are. Can we do anything about these?

Reducing emissions from electricity and heat production will have to come from our leaders. At the time of this writing, the United Nations Climate Summit is going in Scotland and much discussion about this is going on. China, Russia, and India are all concerned about reducing GHG from coal powered plants. This is understandable being that this is the major source of energy for those nations. However, the negative impact of burning coal on the climate is serious and cannot be ignored if the world is serious about reducing, or eliminating, the long-term impacts of climate change. So, the move away from coal is a good start.

Power plant on one of the panhandle estuaries.

Photo: Flickr

The EPA reported in 2019 that United States has seen a decrease in greenhouse gas emissions primarily due to a decrease in energy use and the decrease in the use of coal – showing it can be done3. The United States is discussing reducing the use of coal even further, but not all in congress support this – primarily those who represent states where coal mining is a large industry. But again, the negative impacts of burning coal are there and, if the world wants to “turn this thing around”, we will need to consider doing this. Again, there is little the citizen can do to make these changes other than selecting leaders who are willing to. It is in their hands.

The transportation issue is different… we can make a difference here.

In the U.S. transportation produces 29% of the greenhouse gas emissions, #1. It is only 14% of the problem worldwide. Americans love their cars. We drive everywhere. Most Americans live at least 25 miles from where they work, many live much further, some actually live in a different state. Being work, most of these drivers are traveling alone, carpooling is not a common practice, and mass transit is not available in many communities. So, we sit in traffic jams every morning and evening trying to get to the places we want, and need, and complain of the congestion, wishing the local government could improve traffic flow. One of the reasons we have this problem, and other parts of the world do not, is how we design our cities.

Heavy traffic is common place in the U.S. with our dependence on cars.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Some city planners argue the best way to reduce the transportation issue is by compact development. This is a plan that would have residents live within walking or biking distance of everything they need – home, work, stores, etc. Our ancestors lived this way primarily because they had to, they did not have cars. The wealthy, who had horse and carriage, could live outside of town and ride in when they wanted.

This desire to live outside of the city in more open space could be used in another form of urban development that could still reduce the transportation problem – satellite development. In this method, residents would live in suburb areas that were connected to the urban workplace by mass transit. Imagine living in a suburb where you went to the rail station, climbed on, and traveled over greenspaces (supporting forest and pasture lands) to the urban work area. There are many cities in the U.S. who have this type of system in place, but few travel over greenspaces – they mostly travel over other suburban developments.

However, this would generate crowds at the terminal and the stress that comes with it. It would make it harder to “stop by the store” on the way home – though the stores would be within walking distance in the residential “satellite” area. Walt Disney promoted this idea when he was planning Epcot and used the monorail as an example of how it could be done.

But we love our cars… so, another plan would be what is called corridor development. Here, people would live in the residential satellite suburbs but rather than mass transit into the city, there would be a “freeway” for cars to use. Freeway in this sense meaning nothing but highway… no traffic lights, no stores, nothing the impede traffic until you get there. Think in terms of our interstate system. There are many examples of this design around the country. Even here close to home, highway 98 was diverted around Destin to avoid traffic jams. The idea was there would be a clear road around if you were traveling through. But as we will see, in most cases, this did not work.

Heavy urban development “sprawls” away from the city in many U.S. communities. The “corridor” to work has become congested.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

In most cases we plan a corridor design but along the “freeway” route we build new residential developments – they want stores closer and so strip malls and other commercial developments spring up – these residents and businesses need access to the “freeway”, so traffic lights go up and now the city has basically moved away from the central hub into the suburbs forming what we call a megalopolis. I bet this scenario sounds very familiar. It is happening everywhere – even here in the Pensacola area.

Urban sprawl is a big problem and only makes the transportation issue a larger one. G.T. Miller Jr. mentions that urban sprawl is occurring because

- There is affordable land to do so

- We have automobiles so we can function in the design

- Gasoline is cheap

- And we do not plan our cities well

So, we live in a car dominated society – traveling everywhere – usually alone.

Can we do anything about this?

Many scientists and economists believe the only way to reduce the transportation problem is to make it expensive to use. It is believed that making gasoline more expensive would force many to change their driving habits. Currently gas prices are moving towards $4.00 / gallon. We have seen this before and the driving practices did not change much. Some economists believe you will not see such changes until gas reaches $5.00 or $6.00 / gallon – a price many other developed nations routinely spend. It will be interesting to see.

How high will gas prices have to go before U.S. transportation behaviors change?

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Another idea on the cost side is a gasoline tax to cover the estimated harmful costs of driving. The funds from such taxes could be used to develop mass transit systems, bike lanes, and sidewalks. This is occurring in other parts of the world but would probably not work in the United States. Miller gives three reasons why it would be a hard sell in the United States.

- There would be opposition to any tax.

- Fast, efficient, reliable, and affordable mass transit systems and bike lanes are not widely available in most U.S. communities

- The way our communities are designed… we need cars

Other suggested financial methods would include raising parking fees within the city, and more toll roads.

But while we wait and see where gas prices will go and when people will make changes in their driving habits, is there anything else we could do?

Yes…

Carpooling has been suggested since the 1970s. It does occur but has not caught on as many had hoped. Within our community here in Pensacola there are several “park and ride” parking lots and there usually cars in them.

This carpool parking lot near Pensacola is completely full. Indicating more use of this service.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Carpooling is one method to reduce fuel use and GHG emissions.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

There has been an increase interest in hybrid and electric cars in recent years. One concern for electric was the ability to pull heavy loads, something Americans will require. In just the past year one major auto maker began promoting an all-electric truck they assure has the pulling power of a similar size gas powered truck. One colleague of mine recently bought an all-electric jeep which he assured me has plenty of power to pull. More electric charge stations are appearing in local communities, and it seems this is an option for many.

It was also noted in the EPA report that changing our driving habits (i.e., fast starts, incorrect tire pressure, etc.) does make a difference. I know we have all seen the driver who is speeding – darting in and out of traffic only to be at the same stop light with all others in the end. So, changing HOW we drive can help as well.

As mentioned, agriculture and forestry are not as big of an issue in the U.S. as it is on a global scale. There are numerous BMPs farmers can use to reduce their carbon footprint and restore the natural carbon-sequestration. Most not only help with reducing GHG but save the farmers money. There are financial incentives for them to participate in these BMP programs – and so many farmers are using these BMPs. But none-the-less there are things we can still do in this area.

- Support local farmers who are participating in BMP programs by purchasing their products where/when you can. On a global scale the negative impacts of agriculture are increasing. You may have to do a little homework to see where our farmers are selling their products, but it is good to support their efforts.

- Plant a tree… though our forestry industry is making improvements, many communities are clearing land to expand development. Many of these developments are clearing ALL of the trees and putting few back afterwards. Planting a tree not only helps sequester carbon it has been found that shade from trees can lower internal house temperatures up to 10°F, saving heating and cooling costs as well as the energy needed for these1.

Author and county forester Cathy Hardin demonstrates proper tree planting at a past Arbor Day program. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

And then there is commercial and residential energy use. Something that did not even make it on a global scale.

How can we reduce energy use at home and at work?

There are plenty of ways and we need to consider them. According to the EPA report, energy use in the residential and commercial sector is increasing, not decreasing3.

Let’s begin with smart buildings…

Our home was struck by lighting in 2013 and we rebuilt using as many energy efficient methods as we could. Spray foam insultation, better windows, energy efficient appliances, LED lighting, metal roof, and setting the thermostat smarter have all worked well for us. We are typically billed less than $200 per month for our electricity – and there is more we can do. Your local utility company, and your county extension office, can give you numerous tips on how you can save energy in your home or office.

The 2019 EPA report suggests that greenhouse gas emissions are increasing in the areas of transportation, residential and commercial use, and some agriculture practices. But they are decreasing in energy production, industrial processing, and forestry activities. So, we know we can do this. We just need to step up and do it.

References

1 Miller Jr., G.T., S.E. Spoolman. 2011. Living in the Environment; Concepts, Connections, and Solutions. 17th edition. Brooks and Cole Publishing. Belmont CA. pp. 674.

2 Sources of Greenhouse Emissions. 2021. Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions Data. United States Environmental Protection Agency.

https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/global-greenhouse-gas-emissions-data.

3 Sources of Greenhouse Emissions. 2019. U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions Data. United States Environmental Protection Agency.

https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/sources-greenhouse-gas-emissions

by Rick O'Connor | Nov 4, 2021

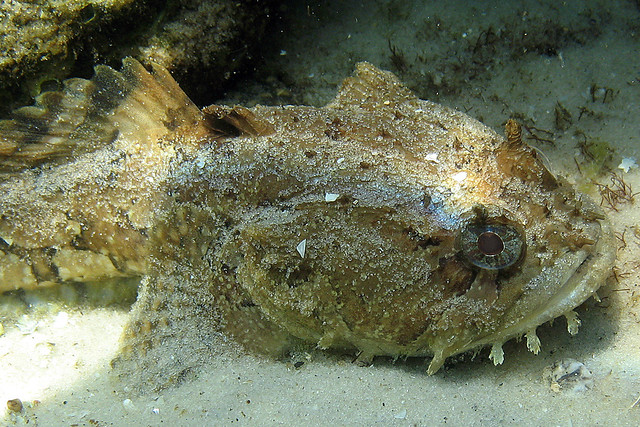

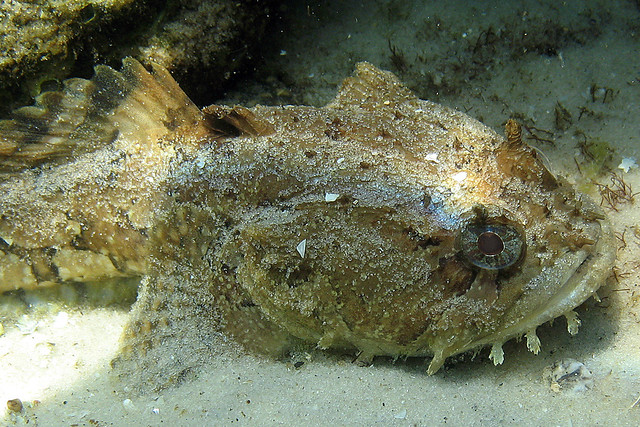

This is a group of fish that few have heard of and many have not seen – or if they saw them, had NO idea what they were – but they a very common in our local waters… the toadfish.

Once you see one, you will know why they call it this. Recently we had a matching game set up for the public to try and match the name of a common seagrass animal with its photograph. The toadfish was one of 20 species on the board. Few knew what it was and most only matched it with the photo through a process of elimination. A common response was “well… this MUST be the toadfish”, though there were just as many who did not see the connection between the name and the look on this fish’s face.

All that said, they are very common here. Snorkeling in our bays I have found them hiding in burrows within the grassbeds, snug against a seawall, and in open spaces within a rock jetty. They are known to hide inside discarded cans and bottles, feeding and eventually growing to large to be able to leave!

They are known for their painful bites; I have personally experienced this. We have captured them when seining the grassbeds. Trying to remove them from the net they are very slimy and difficult to grab. If you get close to their mouth, they will use the teeth they have. Others have been bitten when exploring the inside of a can or bottle left on the bottom. Toadfish belong to the family Batrachoididae and some members of this family are highly venomous. However, of the three species found in the northern Gulf, only the midshipman (Porichthys porosissimus) possess venom, and it is not harmful to humans.

I guess in a word you could say these are ugly fish – hence their name. They are all benthic and remain on the bottom at all times. Most of the swimming they do is to a new hiding place, where they ambush their prey. There are three species found in the northern Gulf of Mexico.

The Atlantic Midshipman

Photo: Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission

The Atlantic Midshipman (Porichthys porosissimus) is a light tan colored fish with dark brown blotches along its side. Because of their light color, they are more common on light colored sand. The ones I have found are on the nearshore bottom of the Gulf side of our barrier island. They posses rows of photophores, cells that can produce light, and these rows of photophores resemble the rows of bright buttons on the 19th century midshipman’s naval uniform – hence their name. This fish has a mean length of eight inches. The midshipman has a more extensive range than the typical “Carolina” Gulf fish. They can be found from Virginia all the way to Argentina; beyond the Brazil limit most “Carolina” fish have. Though not reported on the other side of the Atlantic, nor the Pacific, this species seems to have few barriers impeding its dispersal.

The leopard toadfish.

Photo: Flickr

The Leopard Toadfish (Opsanus pardus) is a larger toadfish reaching 12 inches. They too have a light-colored body with dark markings. It prefers reefs and rocky areas offshore. The only ones I have seen, or captured, were on our artificial reefs. It was noted early on in the lionfish invasion, that lionfish were not as numerous on reefs where leopard toadfish existed. This spawned a hypothesis that leopard toadfish may actually consume lionfish. A small study conducted at a local high school marine science program found that was not the case. I am not aware of any further studies on the relationship between these two, but it could be they just compete for space and the leopard toadfish wins some of these. Though not reported from Argentina, this species does have a large range – including the entire U.S. Atlantic seaboard, the entire Gulf of Mexico, and much of the Caribbean. Again, few barriers to their dispersal.

The common estuarine Gulf toadfish.

Photo: Flickr

The most frequently encountered toadfish is the Gulf Toadfish (Opsanus beta) – also know as the oyster dog, dogfish, or mudfish. This is the largest of the native toadfish at 15 inches. It is most common inside our estuaries living on oyster reefs, burrows in seagrass beds, jetties, and any sunken debris such as pipes, concrete, or pilings. Because of its habitat choice, this toadfish is much darker in color, having some light bars or markings on its side. This is the species that is sometimes found in sunken bottles and cans. This is a Gulf species found throughout the Gulf of Mexico, and some portions of the West Indies, but absent from most of the Caribbean and the Atlantic coast where it is replaced by its close cousin Opsanus tau. There does seem to be a barrier near the Florida straits that impedes its dispersal east and north of the Gulf. There are two species on each side suggesting a long period of isolation from each other and no interbreeding. Again, there is a barrier there.

I am not sure whether you have seen any of the local toadfish while snorkeling or diving. They are occasionally caught on rod and reel, but not often. However, now that you know about them, I am sure you will see one while out on the waters.

Reference

Hoese, H.D., R.H. Moore. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M Press, College Station TX. Pp. 327.

by Rick O'Connor | Nov 4, 2021

At the time of this writing, red tide is still lingering off the Pensacola coast. By the time this is posted it may or may not be. I have had a few questions about red tide while this has been occurring here, and some misconceptions about it – so, now is a good time to try and set the story straight.

The dinoflagellate Karenia brevis.

Photo: Smithsonian Marine Station-Ft. Pierce FL

Red tide is actually caused by a group of small, single-celled marine plants. The one responsible for the red tide in the Gulf of Mexico is called Karenia brevis. Karenia is a naturally occurring dinoflagellate. If I were to pull a water sample off of Pensacola Beach right now I would find it there – albeit in small concentrations – say 300-500 cells in a liter of water. At these concentrations there are no problems. When we say problems, we mean respiratory problems or fish kills. See, Karenia is a dinoflagellate that when irritated or disturbed, will release a toxin – brevotoxin. This toxin is a neurotoxin that is known to kill fish, sea turtles, and marine mammals at high concentrations – greater than 1,000,000 cells / liter. For humans the issue is more of respiratory and eye irritation. Though consuming filter feeding shellfish, such as oysters and scallops, during a red tide can cause serious gastrointestinal problems and possibly hospitalization in humans. This is why the state closes shellfish harvesting when Karenia concentrations reach 5,000 cells / liter.

What causes Karenia concentrations to increase from 500 cells to 5,000 cells, or even 1,000,000 cells / liter?

The same thing that causes all plants to grow – sunlight and nutrients.

Here is where the first misconception arises.

“Red tides are caused by the increase of nutrients in the ocean due to human activity”.

Not exactly correct. Red tides have occurred in the Gulf of Mexico since the colonial period, and the colonists certainly did not discharge enough nutrients to spawn a red tide bloom. No, these blooms occur naturally. Most form off the coast of southwest Florida. There the continental shelf extends about 200 miles offshore before reaching the slope to the deep sea. At this slope there are upwelling currents bringing nutrients from the seafloor to bath these phytoplankton in the warm Florida sun. This combination, along with some other water chemistry needs, fuel the growth of phytoplankton from a few hundred cells / liter to a few thousand, hundred thousand, or even a million cells / liter – an algal bloom. At concentrations of 1,000,000 cells or more the water actually changes color to reddish – hence the name “red tide”.

However…

Today humans ARE discharging large amounts of organic and inorganic nutrients into local waterways. These eventually make their way to the Gulf and can enhance a natural bloom from say 10,000 cells / liter to over 1,000,000 – we can make the situation worse. This typically happens when offshore winds blow the naturally occurring red tides closer to shore to meet our “cocktail of nutrients” and wa-la – an enhanced bloom with enhanced problems.

Dead fish line the beaches of the Florida Panhandle after a coast wide red tide event in October of 2015.

Photo: Randy Robinson

Here in the northern Gulf the conditions to spawn naturally occurring red tides do not typically exist. What we usually see are the blooms generated in southwest Florida pushed northward but weather patterns. At the time of this writing, Escambia County is experiencing a red tide offshore at background/very low concentrations (0-10,000 cells/liter). Though are no reports of fish kills or respiratory issues in humans, but these are happening to our east in Okaloosa, Walton, Bay, and Franklin counties.

The state is aware of the not only the red tide situation, but other harmful algal blooms occurring around the state and has a task force to try and address these. We, of course, can help by reducing the amount of nutrients (fertilizers) we discharge into our local waterways. This would include not only commercial fertilizers, but any plant and animal waste.

References

Red Tide Current Status. 2021. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. https://myfwc.com/research/redtide/statewide/?utm_content=&utm_medium=email&utm_name=&utm_source=govdelivery&utm_term=campaign.

by Laura Tiu | Sep 9, 2021

A Lionfish Removal and Awareness Day festival volunteer sorts lionfish for weighing. (L. Tiu)

The northwest Florida area has been identified as having the highest concentration of invasive lionfish in the world. Lionfish pose a significant threat to our native wildlife and habitat with spearfishing the primary means of control. Lionfish tournaments are one way to increase harvest of these invaders and help keep populations down. Not only that, but lionfish are a delicious tasting fish and tournaments help supply the local seafood markets with this unique offering.

Since 2019, Destin, Florida has been the site of the Emerald Coast Open (ECO), the largest lionfish tournament in the world, hosted by Destin-Fort Walton Beach and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission (FWC). While the tournament was canceled in 2020, due to the pandemic, the 2021 tournament and the Lionfish Removal and Awareness Day festival returned to the Destin Harbor May 14-16 with over 145 tournament participants from around Florida, the US, and even Canada. The windy weekend facilitated some sporty conditions keeping boats and teams from maximizing their time on the water, but ultimately 2,505 lionfish were removed during the pre-tournament and 7,745 lionfish were removed during the two-day event for a total of 10,250 invasive lionfish removed. Florida Sea Grant and FWC recruited over 50 volunteers from organizations such as Reef Environmental Education Foundation, Navarre Beach Marine Science Station and Tampa Bay Watch Discovery Center to man the tournament and surrounding festival.

Lionfish hunters competed for over $48,000 in cash prizes and $25,000 in gear prizes. Florida Man, a Destin-based dive charter on the DreadKnot, won $10,000 for harvesting the most lionfish, 1,371, in 2 days. Team Bottom Time secured the largest lionfish prize of $5,000 with a 17.32 inch fish. Team Into the Clouds wrapped up the $5,000 prize for smallest lionfish with a 1.61 inch fish, the smallest lionfish caught in Emerald Coast Open History.

It is never too early to start preparing for the 2022 tournament. For more information, visit EmeraldCoastOpen.com or Facebook.com/EmeraldCoastOpen. For information about Lionfish Removal and Awareness Day, visit FWCReefRangers.com

“An Equal Opportunity Institution”