by Rick O'Connor | Jul 7, 2025

I read a story about a group of fishermen from Central America who went to sea one day only to have their boat brake down. As they drifted in the current, they immediately went into survival mode rationing the food they had. As their food reserves became low, they would supplement with catching fish – they were fishermen. At one point they ran out of cooking fuel and so began to dismantle parts of the wooden vessel to burn for cooking. There was a point where there was no food for the day. They would go for several days without food, catching fish when they could, seabirds when they landed on the boat, and the occasional sea turtle would hold them for a while. Though they may not have been in shape to play tennis – they were alive and hoping to cross paths with an ocean tanker.

Then they drifted out of the rain belt. They had been collecting rainwater all this time but had entered a portion of the ocean where it did not rain. This changed everything. Though they could go a month without food – one source indicates you can go up to 50 days, and some up to 70 days – you can only go three days without water. The fishermen seemed to understand this. Within a couple of days, they all laid on the bow of the boat awaiting death – they knew this was the end. As luck would have it, a ship did come by and rescued all five. But it shows us the importance of water. Though we sometimes debate which resources are truly needed by humans, we must have water.

The Gulf of Mexico as seen from Pensacola Beach.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

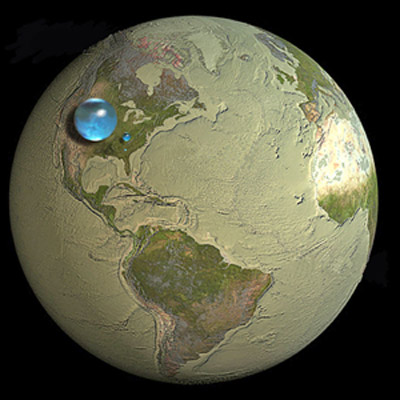

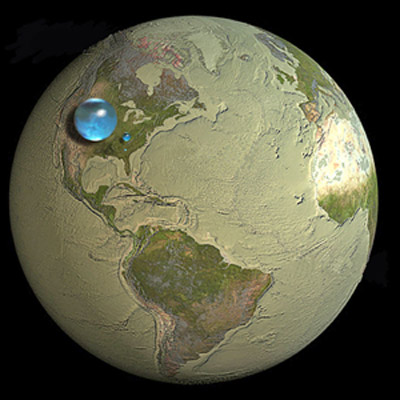

Lucky for us we live on a planet whose surface is covered with it. Jacques Cousteau once said that the planet should have been called “aqua” for there is so little land in comparison – 70% is covered in water. But, as you know, most of the water within the hydrosphere is salt water, and this will not help. The kidneys make urine from water less salty than seawater. So, if you drink seawater, you will urinate more water than you take in and you will die of dehydration.

Only 3% of the water within the hydrosphere is freshwater and 68.7% of that is frozen in glaciers and ice caps, 31% is found as ground water, and less than 1% is found in rivers, lakes, and streams. Though we live on a planet covered in water, very little of it is in a usable form.

This drop represents the total amount of freshwater on the planet. The smaller drop represents freshwater available for use.

Image: U.S. Geological Survey

Humans get their needed water from ground water (aquifers) and surface water (rivers and lakes) sources. With the growing human population, we are overdrawing from both sources. I saw this firsthand while camping in Arizona. There is a place on Lake Powell called Lone Rock. You can drive to the shoreline and camp at the edge of the lake. The first year we camped there we did just that. We drove to a point where there was a slight drop from our spot to the shore of the lake. We came back to this location two years later – went to the same spot where we had camped before – and it had changed drastically. Now from this spot the slight drop was between 20-30 feet – but not to the shoreline – but rather to a hard sand terrace. This terrace extended about 100 yards toward the lake before it dropped another 20-30 feet to the shoreline. It was amazing. The first year we were there we paddled to Lone Rock (in the middle of the lake). Now you could almost walk to it. A local told me he had lived there for 18 years and had never seen it this low.

Lake Powell is the second largest reservoir in the United States. It was created by placing a damn on the Colorado River to create a water source for the people in that area. The drastic loss of water can be explained in two ways. One – a growing human population in an area with little water to begin with, and an increase withdraw of this resource. Two – reduction in rainfall due to climate change. The American southwest does not get a lot of rainfall to begin with. We explained this natural process in our fourth article in this series – Life on Land. Miller and Spoolman note in 2011 that the American southwest receives an average of 16 inches of rain a year. Despite being an arid area there are several major cities – Las Vegas, Los Angeles, Phoenix – with millions of residents who need water. Add to this the large agriculture operations who need water for their crops. Most of their water needs are met by rivers flowing from the Rocky Mountains heading to the sea. These rivers are damned to create reservoirs and the “water grab” begins. Arguments over who should get this water – farmers, residents, entertainment in Vegas – are common. The Water Wars have begun. The population continues to grow, and climate continues to change.

In the American southeast it is different. We average 48 inches of rain a year. Our area of the northern Gulf coast is even wetter. Most think of Seattle as the area with the highest rainfall in the country but in fact the three wettest cities in the U.S. in order are Mobile AL, Pensacola FL, and New Orleans LA. Pensacola historically gets around 60 inches of rain a year. But between 2010 and 2020 the average here increased to 70 inches. The climate models predict that the dry areas of the country will become drier, and the wet areas will become wetter. This certainly seems to be happening. So, locally, the issues are not drought and loss – but flooding.

The amazing thing about this is that in an area where there seems to be plenty of water, we are seeing water deficits. The large amount of precipitation is not recharging the Floridan aquifer (the source of much of our water) but rather falling on impervious surfaces (roads, parking lots, buildings). This water then causes flooding issues and our answer to this is to drain that rainwater into local surface waters and into the Gulf – not recharging the aquifer. As strange as it sounds – we are hearing about Water Wars even here. It is not that we do not have enough water – it is we do not manage it well.

In the next article we will discuss some suggestions on how we might better manage our very much needed water resources.

References

How Long Can You Go Without Food? Verywell Health. https://www.verywellhealth.com/how-long-live-without-food-1132033#:~:text=How%20long%20human%20beings%20can,someone%20can%20live%20without%20food.

Hospice No Food or Water. Oasis Hospice and Palliative Care. https://oasishospice.us/2022/05/17/hospice-no-food-or-water/.

Can Humans Drink Seawater? National Ocean Service. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/drinksw.html.

Where is the Earth’s Water? GRACE: Tracking Water from Space. American Museum of Natural History. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.amnh.org/content/download/154153/2561707/file/grace-passage-1-student-version.pdf.

Miller, G.T., Spoolman, S.E. 2011. Living in the Environment. Brooks/Cole Cengage Learning. Belmont CA. pp. 674.

by Laura Tiu | Jun 6, 2025

The colonial Portuguese man-of-war.

Photo: NOAA

I love summer; going to the beach, snorkeling, kayaking and grilling in the backyard. But summer comes with its own share of challenges. One of my least favorite summer guests is bugs. The list of bugs I dislike is long, but I’d like to focus on a few that like to torment us all.

Mosquitos are one of summer’s bad actors. Mosquito lay their eggs and their larvae mature in both manmade and natural water-holding containers such as bird baths, plants, bucket, used tire and holes in trees. Some mosquitos just bite while others carry disease. The easiest way to get rid of mosquitos is to get rid of any water-holding containers in the area.

Ants, in particular fire ants, are another unwelcome summer arrival. This invasive species is aggressive, and their painful stings can injure both humans and animals. Fire ant nests look like large mounds of dirt and typically have multiple openings. You must kill the queen to completely eliminate a colony. Even if the queen is killed, surviving ants may inhabit the mound or make a new mound until they die off. Some treatments that may work to get rid of these pests include baits, pesticides and boiling water.

Many biting flies, yellow flies are my least favorite, persistently attack man and animals to obtain a blood meal. Like mosquitoes, it is the female fly that is responsible for inflicting a bite. These biting flies like shady areas under bushes and trees and wait for their victim to pass by. They typically attack during daylight hours, a few hours after sunrise and two hours before sunset. Currently there are no adequate means for managing populations. Traps are sometimes effective in small areas such as yards, camping sites, and swimming pools.

In the water, jellyfish are the most common summer pest. While not bugs, their reputation for stinging people puts them in a similar category with the above-mentioned pests. Sea lice, actually the larval form of the thimble jellyfish, is a common near shore pest, while Portuguese Man-O-War and the box jellyfish can give a very painful sting. Another type, comb jellies, are not true jellyfish and do not sting. I you get stung, rinse the sting site with large amounts of household vinegar, or jelly-fish-free ocean water, for at least 30 seconds. Do not rub sand or apply any pressure to the area or scrape the sting site.

The University of Florida – IFAS has several good publications with information about these pests and more detail on how to manage them. Check out these publications if you, like me, have had your fill of summer pests.

Florida Container Mosquitos: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/IN1315

Ant Control – https://sfyl.ifas.ufl.edu/lawn-and-garden/sustainable-fire-ant-control/

Yellow Flies – https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/IN595

Jellyfish – http://nwdistrict.ifas.ufl.edu/nat/tag/jellyfish/

by Dana Stephens | May 12, 2025

Spring is a time of change. Spring brings changes in our waters as well. Some of these changes are visible on top of the water and cause concern among water users and viewers. Let’s dispel some of these concerns associated with the spring season.

Sometimes, water users and viewers notice what appears to be oil floating on top of the water. Could this be oil? Potentially. Could this not be oil? Most likely. Plants perish, and decomposition occurs, typically during the spring and fall seasons of the year. Much of the decomposition that happens in spring is associated with the initial growth and development of plants. Bacteria living in the soils within and around the water break down the perished plants. These bacteria are decomposing the old plant material. The waste product produced from the bacteria’s decomposition of the old plant material is an oily substance. The oily sheen on the water is a waste product of bacteria. Frequently, the oil accumulates in portions of water where there is little to no water movement. As the decomposition process completes, the oily sheen should lessen over the next few days to weeks. This bacteria-produced oil from decomposition is a natural process.

Petroleum-based oil seen on water is not a natural process. Petroleum-based oil could enter water from various sources, such as but not limited to transportation spills, stormwater runoff, and improper disposal of products containing oil. Like the oily substances produced by bacteria during decomposition, petroleum-based oils will float on top of the water and accumulate where there is little to no water movement.

Here are some tips to identify the difference between oils in water:

|

Bacteria-produced Oil |

Petroleum-based Oil |

| Appearance |

Oily sheen on top of water with little to no difference in color throughout |

Oily sheen on top of water with differences in color throughout (may even appear like a rainbow) |

| Touch

(use a stick) |

When disturbed, the sheen breaks away easily with irregular patterns and does not reform. The oil will not adhere to the stick. |

When disturbed, the sheen swirls, elongates, and does reform. The oil may adhere to the stick. |

| Odor

(not always present) |

Strong organic, musty, or earthy smell. |

Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) smelling like gasoline or diesel fuel. |

Another sheen on our waters that is frequent during Florida’s springtime is pollen. Pine, tree, and weed pollen accumulate on top of water, especially in areas with little or no water movement. If the sheen on the water is yellow, orange, or sometimes white, this is most likely due to pollen. Think about how pollen shows on a car in Florida during spring…our waters can show the same to some extent.

Let’s give it a try! See if you can identify the sheens in water in each photo—answers at the bottom of the page.

Photo 1

Photo 2

Photo 3

Photo 4

Photo 5

Photo 6

Keep Scrolling For Answers!

.

.

.

.

.

.

PHOTO ANSWERS: Photo 1: Bacteria-produced oil sheen. Photo 2: Pollen sheen. Photo 3: Petroleum-based oil sheen. Photo 4: Pollen sheen. Photo 5: Petroleum-based oil sheen. Photo 6: Mixture of bacteria-produced oil and pollen sheen. Note all photos were obtained from Adobe Stock Photos.

by Rick O'Connor | Mar 14, 2025

If green algae are difficult to find in the northern Gulf because most prefer freshwater, and rocky shorelines, brown are difficult because the group prefers colder water, as well as rocky shorelines – but we do have some here.

Brown algae get their color because the ratio of photosynthetic pigments in their cells favors the xanthophylls – which produces a yellow-brown color. Like most macroscopic algae, they attach to the hard bottom using a holdfast and then extend their stipe and blade into the water column to absorb light. One group of brown algae are the largest of all seaweeds, the giant kelp Macrocystis. In the nutrient rich waters off California this seaweed will grow up to one foot a day and can reach heights of up to 175 feet tall. Since seaweeds do not possess true stems, or any wood, what holds this giant seaweed up are air filled bladders called pneumatocysts – structures found on other brown algae and are unique to the group.

The largest, fastest growing seaweed – giant kelp.

Photo: NOAA

Many species are popular with seafood dishes, such as Nori. Others produce a carbohydrate known as algin that is extracted and used as a food additive. You may have heard “ice cream has seaweed in it”. What it actually has is algin. This carbohydrate acts as a smoothing agent for products. Solids should be solid – like frozen ice cream – but, as you know, we do not want our ice cream solid. So, for a period of time, the algin keeps the ice cream smooth and creamy. Algin is used in toothpaste, lipstick, and icing on cakes for the same reason.

But along the northern Gulf coast, brown algae are not common. Despite preferring marine waters, they do prefer colder water and, like most seaweeds, need a hard substrate to attach their holdfast. But by exploring our local rock jetties and seawalls we do find some. One in particular is the common rock weed – Dictyota. This sessile seaweed branches out and resembles small trees. But the most common, and most recognized brown algae on our coast is Sargassum.

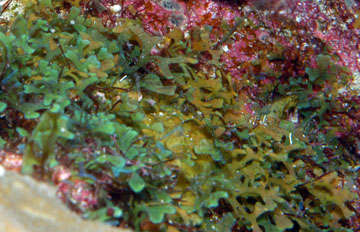

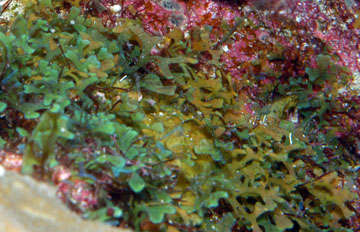

The brown algae Dictyota.

Photo: NOAA

Sargassum has found a way to deal with an environment where little hard bottom is present. Using the characteristic air bladders allows it to float at the surface to absorb the much needed sunlight. Because of this ability to float, Sargassum can be found all across the oceans, and often form large mats that cover miles of open sea and extend several feet down. It actually creates a whole new ecosystem in the middle of the sea. The major ocean currents rotate like a hurricane and, like a hurricane, the center – the “eye” – is calm. Within this calm huge mats of Sargassum collect. The ancient sailors called the center of the Atlantic Ocean the “Sargasso Sea”. But as the large currents spin, sections of this large mat “spin off” and are pushed across the ocean. Much of it heads towards Florida, the Gulf, and eventually to the northern Gulf.

If you grab a mask and snorkel and swim within the Sargassum before it reaches the waves, you will encounter a whole community of creatures that live here. Sargassum crabs, Sargassum fish, and even seahorses live within it. There are shrimps, worms, and even mollusks. When baby sea turtles head offshore after hatching, many seek out these Sargassum mats to both hide in, and feed within. They will spend their youth here before returning back to shore for different prey.

However, once many of these creatures sense the waves breaking, and now the mat is about to wash ashore, they will move to mats further offshore. That said, picking through the Sargassum on the beach may still yield some interesting creatures.

Sargassum.

In recent years the amount of Sargassum washing ashore has increased and become problematic – particularly in southeast Florida and the Florida Keys. At times, mounds three feet high have been found. Those communities are working on methods to deal with the problem. But here locally, these mats are a new world to explore.

References

Giant Kelp. Monterey Bay Aquarium. https://www.montereybayaquarium.org/animals/animals-a-to-z/giant-kelp.

by Laura Tiu | Mar 7, 2025

As spring approaches, I’ve been receiving more calls from local pond owners looking for advice on preparing their farm ponds for the season. Managing a pond in the Florida Panhandle can be tricky—especially when dealing with spring-fed ponds. While these ponds are often beautifully clear, their constant water turnover makes management a challenge.

As spring approaches, I’ve been receiving more calls from local pond owners looking for advice on preparing their farm ponds for the season. Managing a pond in the Florida Panhandle can be tricky—especially when dealing with spring-fed ponds. While these ponds are often beautifully clear, their constant water turnover makes management a challenge.

If you’re wondering how to get your pond ready for spring, here are some key considerations and resources to help guide you.

Start with a Water Quality Test

The first step in assessing your pond’s health is testing the water. I always recommend that pond owners bring a pint-sized water sample in a clean jar to their local Extension Office for analysis. Keep in mind that not all offices offer this service, and public testing options are limited. However, private labs and DIY testing kits are available—though they can be costly.

The most important parameters to check are pH, alkalinity, and hardness: pH should ideally range between 6 and 9 for a healthy fish population. Local ponds often hover around 6.5, making them slightly acidic.

Alkalinity and hardness measure the water’s ability to neutralize acids and buffer against sudden pH changes. For optimal pond health, alkalinity should be at least 20 mg/L, but many local ponds fall below this level.

Improving Pond Water Quality

If your pond’s water quality is less than ideal, there are two common ways to improve it: liming and fertilization.

Applying Agricultural Lime: Properly adding agricultural lime can raise alkalinity and stabilize pH levels. However, in high-flow ponds, lime tends to wash away quickly, making this method ineffective for ponds with constant discharge.

Fertilizing to Boost Productivity: Fertilization increases phytoplankton growth, which supports the pond’s entire food web, benefiting juvenile fish and invertebrates. Unfortunately, like lime, fertilizer is quickly washed out of high-flow ponds, making it ineffective in these cases.

Making the Best of Your Pond

If your pond has a continuous discharge due to spring flow, the best approach may be to embrace its natural clarity, even if it doesn’t support a thriving fish population. However, if your pond retains water without frequent outflow, you may be able to enhance its productivity with the right amendments.

For personalized guidance, contact your local UF/IFAS Extension Office. You can also start by reviewing this helpful fact sheet: Managing Florida Ponds for Fishing. By understanding your pond’s unique characteristics, you can make informed decisions to keep it healthy and enjoyable throughout the season.