by Thomas Derbes II | Aug 10, 2024

Many of us are given that Birds and the Bees talk; another majority have had to give it as an adult to their kids. It is usually an awkward talk, but someone had to step up to the plate and put on a straight face. I am happy to be the one today to discuss one section of the Birds and the Bees of the Sea, batch spawning. Batch spawning, also known as broadcast spawning, is the coordinated release of gametes (sperm and eggs) into the water column. Batch spawning is not just relegated to fish, many species of invertebrates also batch spawn. Some of the most commonly encountered batch spawners include Florida Pompano (Trachinotus carolinus), Eastern Oyster (Crassostrea virginica), Red Drum (Sciaenops ocellatus), Red Snapper (Lutjanus campechanus), and Gag Grouper (Mycteroperca microlepis), to name a few. In fact, most gamefish species in the Gulf of Mexico are batch spawners. This has its advantages, but also has its major disadvantages. We will dive headfirst into a few representative species of saltwater organisms that batch spawn, and their respective life stages to help shed some light on reproduction in the marine world.

Baby Snapper – Thomas Derbes II

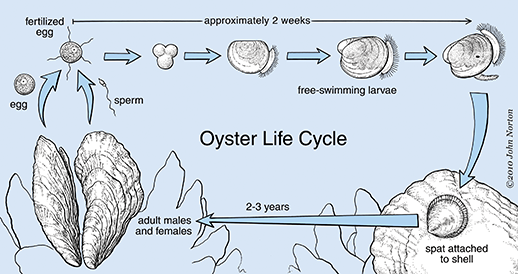

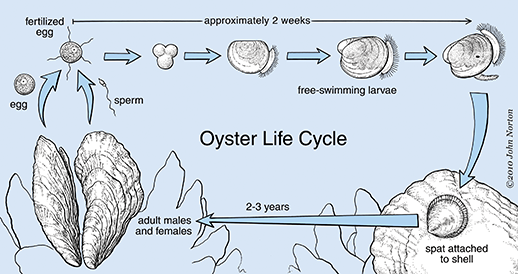

Eastern Oysters are a perfect representative for invertebrate batch spawning. I have gone over their life cycle in a previous article (Click Here), but I will just quickly go over their spawning habits and life history. Eastern Oysters typically spawn during the changing of the seasons, particularly from Spring to Summer and Summer to Fall. As humans, we see these changing temperatures and weather fronts as an opportunity for a new wardrobe, but these changes are triggers for oysters to spawn. Once one oyster releases their gametes into the water all of the mature oysters in the area will start releasing their gametes. Waiting to sense for other gametes in the water is a very smart tactic. This allows for a coordinated spawn between masses of oysters and (hopefully) increases the fertilization rate of the eggs. Since oysters cannot move, batch spawning is the most beneficial way for them to reproduce. Females can release anywhere from 2 to 70 million eggs in one spawning event, with only a dozen or so becoming adults. Since they are batch spawners, the larvae are left unprotected by the parents and suspended in the water column for the first few weeks, leaving them susceptible to predation by filter feeders and bad water quality. Once the larvae have reached the pediveliger stage, they will settle out and “walk” along the bottom of the estuary until they find a suitable place to call home, usually another oyster or hard substrate. After 1-3 years, the oyster will mature and begin batch spawning when conditions are ripe, and the cycle continues!

The Oyster Life Cycle – Maryland Sea Grant

Fish in the Lutjanidae (snapper) family are the perfect representative for batch spawning with fish. Snappers of all species are known to congregate and have mass spawning events typically around a full moon. The mutton snapper (Lutjanus analis) of South Florida and the Florida Keys are very well known for their ability to form massive congregations of tens of thousands of fish along the reef starting in April. Once the spawning commences, the mutton snapper will form a small subgroup of up to 20 fish in the late afternoon. This subgroup will travel to depths of up to 100ft to perform their spawning event. During this event, the female will signal to the males that she is about to release her eggs. The males will then rub up against the side of the female snapper, helping her release eggs while simultaneously releasing their milt (sperm). When the milt is released, the sperm is activated by the seawater and begins to swim. Eventually, the eggs are fertilized and an embryo is formed.

Massive Two-spot red snapper aggregation ready to spawn in Palau – R.J. Hamilton

18 – 24 hours later, the embryo is now a larval fish consisting of a yolk sac and lacking a mouth, eyes, and most organs. The yolk sac consists of amino acids and other nutrients that provide energy to the developing larvae. These larval fish have until their yolk sac runs out to develop the lacking vital organs, which usually takes between 24 – 48 hours. Only a very small percent of juvenile snapper make it to adulthood due to predation during their larval stage and predation as a juvenile. In fact, sharks and other large predators will prey on the snapper as they congregate and spawn, and filter feeders like manta rays are known to pass through an active spawning congregation to consume all the fertilized eggs and larval fish.

Well, I hope I didn’t scar anyone too badly. Batch spawning is fairly common in the marine biology world, and you can sometimes experience a spawning event without even knowing it. As for positives, this allows for many eggs to be fertilized at a time multiple times a season and for the larval fish and shellfish to be distributed through the estuary and reef via tides and waves. A major negative is the vulnerability of the juvenile and larval fish and shellfish, but the sheer number of eggs produced and fertilized helps outweigh the high potential for predation and unexplained loss of fertilized eggs and juveniles.

References:

Oyster Spawning: https://www.umces.edu/news/the-life-of-an-oyster-spawning

Mutton Snapper Species Spawning Profile: https://geo.gcoos.org/restore/species_profiles/Mutton%20Snapper/

Mutton Snapper Aquaculture Profile: https://srac.msstate.edu/pdfs/Fact%20Sheets/725%20Species%20Profile-%20Mutton%20Snapper.pdf

by Rick O'Connor | Aug 10, 2024

I bet that for most of you, this is not only a worm you have never seen – it is a worm you have never heard of before. I learned about them first in college, which was almost 50 years ago, and have never seen one. But, other than the earthworm, the world of worms is basically hidden from us.

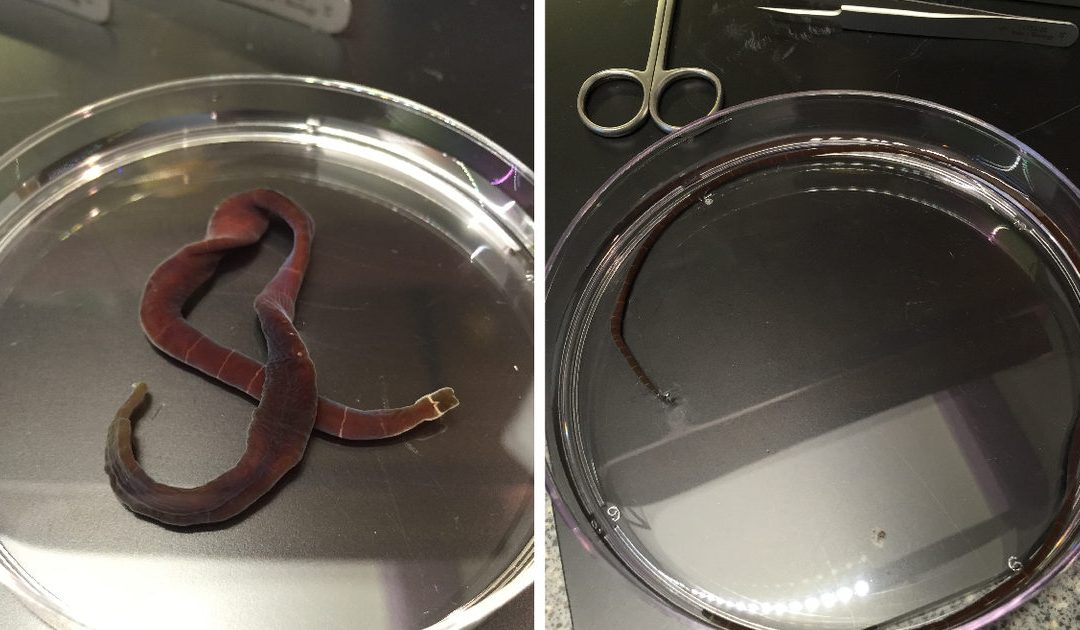

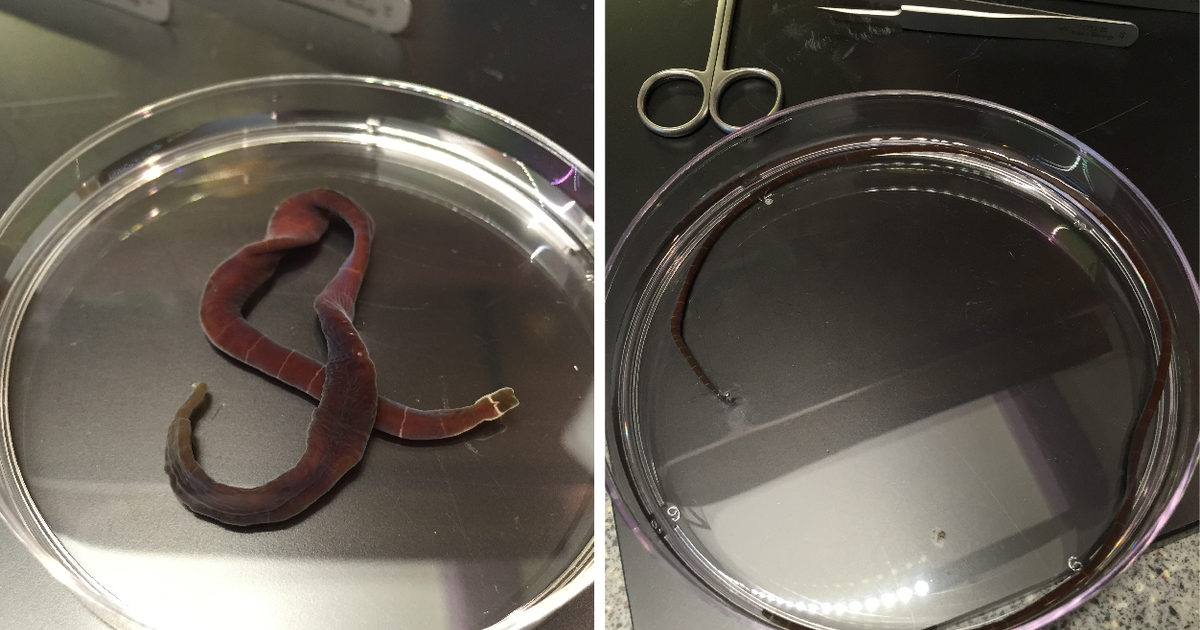

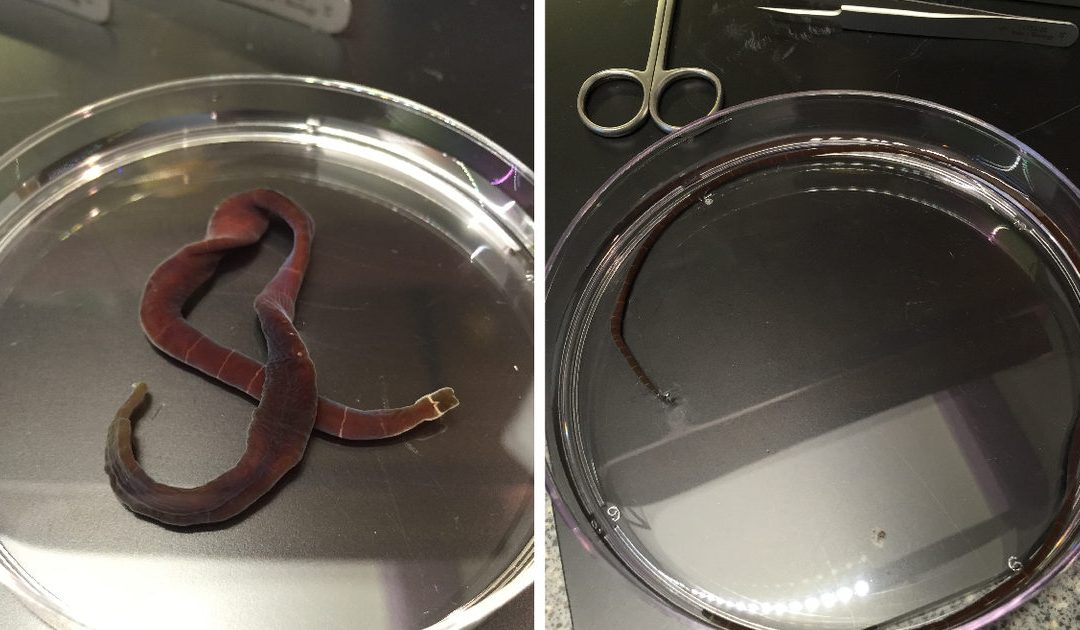

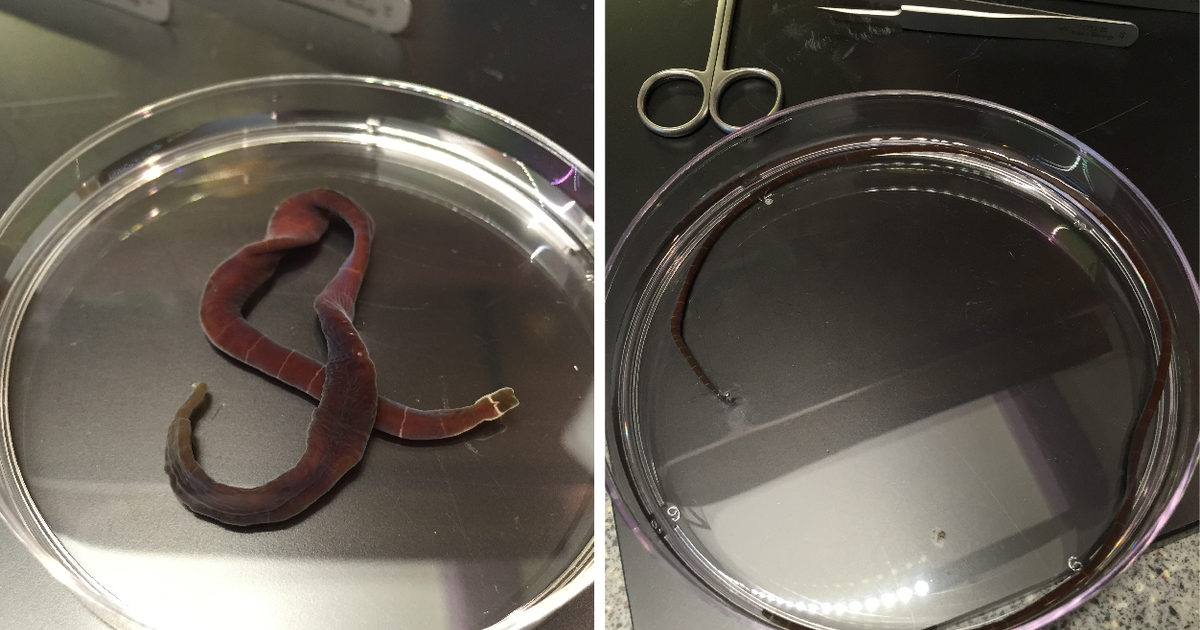

A nemertean worm.

Photo: Okinawa Institute of Science

Nemerteans are a group of about 1300 species in the Phylum Nemertea and are often called ribbon or proboscis worms. They do possess a proboscis used to capture prey. Most are marine and live on the bottom both near the beach and a great depth. They are more temperate than tropical and do have a few parasitic forms.

Adult Nemertea Worms – Terra C. Hiebert, PhD, Oregon University

In appearance they resemble flatworms but are larger and more elongated. Most are less than 20cm (8in) but some species along the Atlantic coast can reach 2m (7ft). The head end can be lobed or even spatula looking. Some species are pale in color and others quite colorful. Most nemerteans move over the substrate on a trail of slime produced by their skin. Some species can swim.

As mentioned, the proboscis is used to capture prey. It is a tube-like structure held in a sac near the head. When prey is detected, they can launch the proboscis out and over the victim. Sticky secretions help hold on to the prey while they ingest. Many species are armed with a stylet, dart, that is attached to the proboscis and is driven into the prey like a spear. From there toxins, secreted from the base of the proboscis are injected into the prey.

For many species the proboscis is connected to the digestive tract via a tube, there is no true mouth, but they do possess an anus. They are all carnivorous and feed on a variety of small living and dead invertebrates. Their menu includes annelid worms, mollusk, and crustaceans.

Nemerteans do possess a brain and most find their prey using chemoreception, though some species must literally bump into their prey to find it. They have multiple eyes that can detect light, and, like the true flatworms, they are negatively phototaxic. They are nocturnal by habitat and is probably why most of us have never seen one.

Many nemerteans, particularly the larger ones, have a habit of fragmenting when irritated, creating new worms. Most species have separate sexes and fertilization of the gametes is external (fertilization occurs in the environment).

Nemerteans are an interesting group of semi-large, sometimes toxic, hunters who prowl through the marine waters at night hunting prey. Seen by few, maybe one evening, while exploring or floundering, you may see one.

In Part 3 we will begin to explore a group of worms that are more round than flat. The Gastrotrichs.

Reference

Barnes, R.D. (1980). Invertebrate Zoology. Saunders Publishing. Philadelphia PA. pp. 1089.

by Rick O'Connor | Aug 10, 2024

I was recently conducting a survey for diamondback terrapins from my paddleboard in a small estuarine lagoon within the Pensacola Bay System. Even if we do not find our target species during these surveys – I, and our volunteers, see all sorts of other cool wildlife. On this trip I was treated to nesting osprey, a kingfisher, large blue crabs, and even a swimming eel. But one neat encounter was the numerous stingrays.

The Atlantic Stingray is one of the common members of the ray group who does possess a venomous spine.

Photo: Florida Museum of Natural History

They were lying in the sand and grassbeds, lots of them, and they all seemed to be of one species – the Atlantic stingray. My brain immediately went to “breeding season”, but when I checked the literature, I found that it was not breeding season, but pupping season – the babies were being born.

Atlantic Stingray (Dasyatis sabina) are true stingrays in the family Dasyatidae. This means they do possess the replaceable serrated venomous barb that makes these animals so famous. They are one of the smaller members of this family. Females can reach a disk width of two feet while the smaller males will only reach about one foot. Atlantic stingrays are a warm water species, migrating if they need to find suitable temperatures. They have been found in water as deep as 80 feet but are more common in the warmer shallower waters near shore. They are very common in our estuaries and being euryhaline (they tolerate a large range of salinity), are found in freshwater systems. There is a population that lives in the St. Johns River. Atlantic stingrays feed on a variety of benthic invertebrates and have special cells in the nose to detect the weak electric fields their prey give off while buried in the sediment. They also like to bury in the sand to ambush prey as they move by.

Breeding occurs in the fall. The smaller males possess two modified fins called claspers connected to their anal fins that are used to transfer sperm to the female. The males have modified teeth they can use to bite the fins of the females. They do this to hold on and make sperm transfer more successful.

The females do not begin to ovulate until spring. So, though they receive the sperm in the fall, fertilization does not occur until the spring. Instead of laying eggs, as some rays and skates do, baby Atlantic stingrays develop within the mother. This is not the same as mammals, who produce a placental to feed the developing young, but more like an internal egg with no hard shell. The embryo is attached to, and feeds from, a yolk sac. Gestation takes about 60 days at which time the yolk sac is depleted, and the young must emerge. Birth usually occurs in late July and early August, and each female will produce 1-4 small pups whose disk are about 10cm (4in.) wide. It was this birthing/pupping period I witnessed.

I returned the following day to search for terrapins and the number of stingrays was significantly fewer. It may be that the birthing process is fast, and the adults leave the coves afterwards. It may have been because that day was the day Hurricane Debby was making landfall east of us and the water levels were abnormally high – something the rays may have noticed and decided to leave – I am not sure.

I was really hoping to see the young rays swimming around – I did not – but plan to search again soon. Stingrays make many people nervous. I witnessed several adult rays whose tails had been cut off – which is very unfortunate – but they are actually cool creatures and fun to watch while paddleboarding. Maybe I will see a baby soon.

References

Dasyatis sabina. 2023. Florida Museum of Natural History. https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/discover-fish/species-profiles/dasyatis-sabina/.

Johnson, M.R., Snelson Jr., F.F. 1996. Reproductive Life History of the Atlantic Stingray, Dasyatis sabina (Pisces, Dasyatidae), in Freshwater St. Johns River, Florida. Bulletin of Marine Science, 59(1): 74-88.

by Laura Tiu | Aug 10, 2024

My son and his girlfriend were visiting last week and wanted to go fishing. Since she had never been deep sea fishing before, we decided that the best course of action would be to take the short four-hour trip on one of Destin’s party boats.

Party boats, also known as a head boat, are typically large boats from 50 to 100 feet long. They can accommodate many anglers and are an economical choice for first-time anglers, small, and large groups. The boat we went on holds up to 60 anglers, has restrooms, and a galley with snacks and drinks, although you can also bring your own. The cost per angler is usually in the $75 – $100 range and trips can last 4, 6, 8, or 10 hours.

We purchased our tickets through the online website and checked in at the booth 30 minutes before we departed. Everyone gets on and finds a spot next to a fishing pole already placed in a holder on the railing. For the four-hour trip, it is about an hour ride out to the reefs. On the way out, the enthusiastic and ever helpful deckhands explain what is going to happen and pass out a solo cup of bait, usually squid and cut mackerel, to each angler. When you get to the reef, you bait your hooks (two per rod) and the captain says, “start fishing.”

The rods are a bit heavy and there are some tricks you need to learn to correctly drop your bait 100 feet to the bottom of the Gulf. The deckhands are nearby to help any beginners and soon everyone is baiting, dropping, and reeling on their own. There are a few hazards like a sharp hook while baiting, crossing with your neighbor’s line and getting tangled, and the worst one, creating a “birds nest” by not correctly dropping your line. Nothing the deckhands can’t help with.

When you do finally catch a fish, you reel it up quickly and into the boat where a deckhand will measure it to make sure it’s a legal species and size and then use a de-hooker to place the fish in your bucket. After about 30 to 40 minutes, the captain will tell everyone to reel up before proceeding to another reef. At this time, you take your fish to the back of the boat where the deckhands put your fish on a numbered stringer and on ice.

For the four-hour trip, we fished two reefs. We had a lucky day with the three of us catching a total of 16 vermillion snapper, the most popular fish caught on Destin party boats. It’s a relaxing ride back to the harbor during which the deckhands pass the bucket to collect any tips. The recommended tip is 15-20% of your ticket price. These folks work hard and exclusively for tips, so if you had a good time, tip generously.

Once back in the harbor, your stringer of fish is placed on a board with everyone’s catch and they take the time for anyone that wants to get some pictures with the catch. Then, you can load your fish into your cooler, or the deckhands will clean your fish for you for another tip. If you get your fish filleted, you can take them to several local restaurants that will cook your catch for you along with some fries, hush puppies and coleslaw. It is an awesome way to end your day.

A happy angler after a party boat excursion.

by Rick O'Connor | Jul 19, 2024

In this series we have found that in the 1970s and 1980s climate scientists developed models that could predict the effects of a warming planet on society.

We saw that society, at that time, had little faith in the accuracy of those model predictions.

We also saw that natural occurring events, like tropical storms and the eruption of Mt. Pinatubo, gave climate scientists an opportunity to test their models – and their models past with flying colors.

We have seen the development of international councils and panels to address climate change, enhance the models, and provide advice on how to turn the potential negative effects of a warming planet around.

We have also seen that many of the predictions from those early models are occurring, some have occurred faster than the models indicated they would.

So…

Is there anything we can do about it?

The answer is pretty simple really. Just like those trying to lose weight – you need to either reduce the calories you take in and/or burn those calories off. With climate you need to reduce the amount of carbon you put into the atmosphere and/or remove the excess carbon.

In 2006 NASA climate scientists stated that we had about a decade to make some serious policy changes to avoid irreversible climate change that could cause economic and ecological havoc. They mentioned we needed to cut CO2 emissions between 50-85% by 2050. Their suggestions could be found on both sides of the solution model.

| Reducing Greenhouse Emissions |

Removing Greenhouse Gases |

| Cut fossil fuel use (especially coal) |

Add technologies to both smokestacks and combustible engines to remove CO2 in their emissions |

| Shift from coal to natural gas |

Sequester CO2 by planting trees |

| Improve energy efficiency |

Sequester CO2 underground |

| Use more renewable energy and make these technologies available in developing countries |

Use better land management practices in agricultural |

| Reduce deforestation |

Sequester CO2 in the deep ocean |

| Use more sustainable agriculture and forestry methods |

|

Other methods that could help reduce CO2 emission…

- Increase the fuel efficiency of our cars. One target had vehicles getting 60 mpg by 2057.

- Reduce the distance we drive each year. One target had no more than 5000 miles/year.

- Cut electricity use in homes and offices by 25%.

- Increase solar power use.

- Increase wind power use.

- Increase the use of biofuels.

- Stop deforestation.

- Better methods in agriculture.

- Install scrubbers in fossil fuel burning engines to clean emissions.

So… How are we doing with these?

Cars are more fuel efficient than they were decades ago. Many have turned to electric cars, or hybrids.

It seems that we are driving MORE miles each year – not less. Our society is designed around the need for an automobile – we cannot function without one. And our city planning seems to have us living farther and farther from our work. When I was younger there was much talk about mass transit to reduce traffic and emissions. In large cities where this was already ongoing it continues. But in the other parts of the county this has not really caught on. We are still driving too much.

There are methods of making homes more efficient. My wife and I adopted some of these as we rebuilt our house after a fire. Compared to neighbors and friends, our power bills are much lower. Many of these methods and technologies are being used in new home developments and are encouraging.

Solar farms are increasing – even along I-10 in the Florida panhandle. There is some concern that these solar farms are replacing food farms, but there is an attempt to do this. Out west we see the same.

The same can be said for wind farms – at least out west.

According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, biofuel production has increased each year since 1980.

Deforestation has not slowed. As a matter of fact, many developments in the Florida panhandle begin by removing ALL trees. In some cases, they replace lost trees with saplings in the new neighborhoods. But a major source of carbon removal has been removed from the system. There is much more that needs to be done with this issue.

Speaking for the farmers in the Florida panhandle – yes… many have turned to better land management practices to protect their land and reduce, or sequester, carbon.

“Scrubber” in internal combustion engines is required by law in the U.S.

Despite some of these positive changes, carbon in our atmosphere continues to increase – not decrease. Part of this is because this is a global issue and that all of human society must work together to reduce greenhouse emissions. Some countries are doing better than others. There are international summits every few years to discuss what the world should do to tur the tide on climate. But all countries need to attend, particularly those producing the largest amount of greenhouse gases.

Here at home, there is resistance to reducing the use of fossil fuels, so many programs have not moved as far forward as they need to move. It is also important to understand that even with the behavior changes we seek, it will take time to undo the damage already done. We will not see improvement right away. Enacting new programs and technologies now could take over 100 years to see the impacts. It is important to understand that the longer we put changes off, the longer it will be before we see any positive benefits from those actions.

There is the concern that the political and public will is still not there to make these changes happen. But they will need to if we are to see things begin to improve.

Until then – you can do your part. Use fossil fuels as little and efficient has you can. Plant trees to help remove carbon dioxide and shade your house so you need less air conditioning. There are many other things you can do to help turn the tide on climate. Check with your local extension office for more ideas.