by Rick O'Connor | Nov 15, 2024

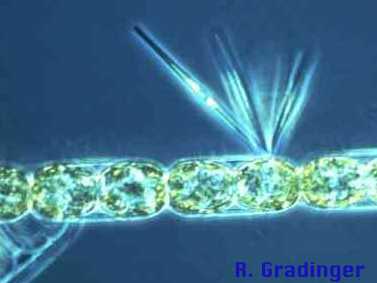

Much of the phytoplankton found in the waters for the northern Gulf of Mexico are diatoms and dinoflagellates. We wrote about diatoms in our last article, here we will meet the dinoflagellates.

Like diatoms, dinoflagellates are microscopic phytoplankton drifting in the surface waters of the Gulf by the billions. We mentioned how abundant diatoms were, in the warmer seas, dinoflagellates are even more abundant. You collect them using a plankton net as you would diatoms. Observing them under the microscope they differ in a couple of ways. One, their shell is not made of clear silica but rather plates of cellulose with silica mixed in. Like diatoms, dinoflagellates possess several forms of chlorophyll but instead of fucoxanthins they possess carotenoids – giving them a brownish/red color. They also possess two hair-like tails called flagella – hence their name “dinoflagellate”. One flagella extends head to tail, the other encircles the dinoflagellate across their “girdle”. These flagella allow the cells to adjust and orient their position in the water column.

Dinoflagellates are microscopic plant-like plankton that possess two flagella.

Image: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

As with diatoms, dinoflagellates exist in the sunlit surface waters serving as “grasses of the sea”. They are an important part of the food chain and, along with their diatom cousins, produce about 50% of the world’s oxygen. But some members of this group are known for other roles they play.

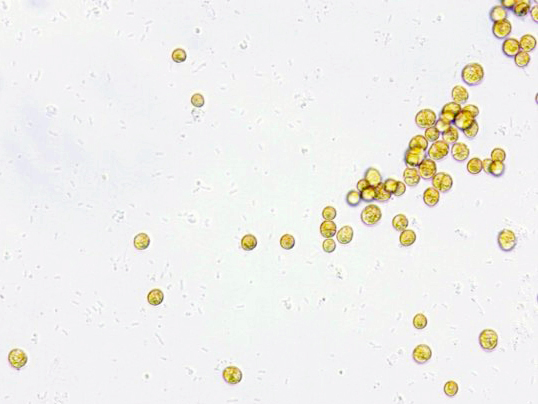

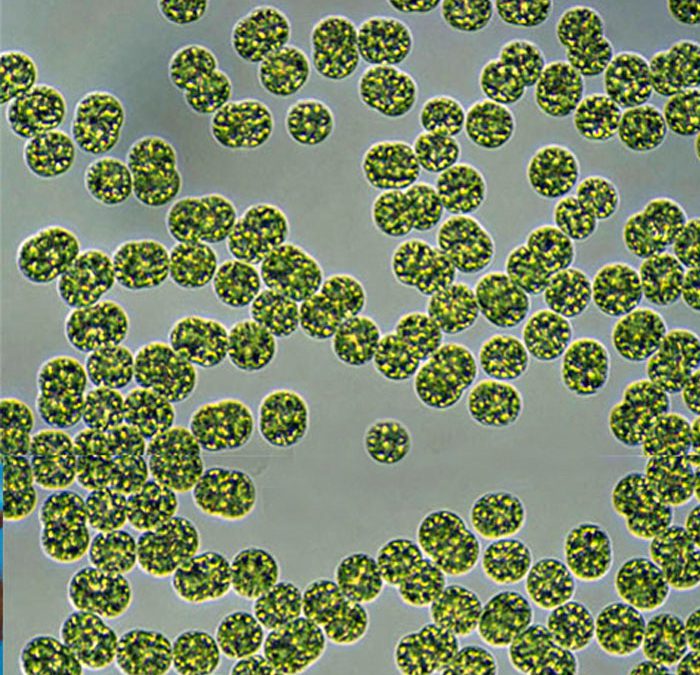

Karenia brevis is the dinoflagellate primarily responsible for red tide in Florida. A plankton tow will find these organisms are always present – usually 1,000 cells/liter of water or less. Under certain conditions, these dinoflagellates begin to replicate in great numbers. Their numbers are large enough that the water will often change to a “reddish” color. In this case we are talking 1 million cells/liter or more. When disturbed, they will secrete a toxin – brevotoxin. This toxin can cause a variety of issues for marine life – and humans. Gastrointestinal, neurological, and respiratory problems in humans have all been associated with it. Red tides are famous for the large fish kills they generate and the mortality in marine mammals.

Being “plant-like” warm waters, sunlight, and nutrients will trigger a bloom. These blooms have been occurring for centuries and were logged by the Spanish explorers. Often, they generate offshore where the sunlit calm waters of the Florida shelf are bathed in nutrients from ocean currents coming from the seafloor. When wind conditions are right – these offshore blooms move inshore where they meet the nutrient rich discharge from rivers and estuaries – enhancing the blooms. Much of this discharge has higher levels of nutrients due to the actions of humans – such as fertilizers, animal and human waste.

Red tides are quite common off southwest Florida – happing frequently during the winter months. In the northern Gulf they are not as common. We do get blooms occurring here, though most are in the eastern panhandle, but sometimes the weather will drive blooms generated in southwest Florida up our way.

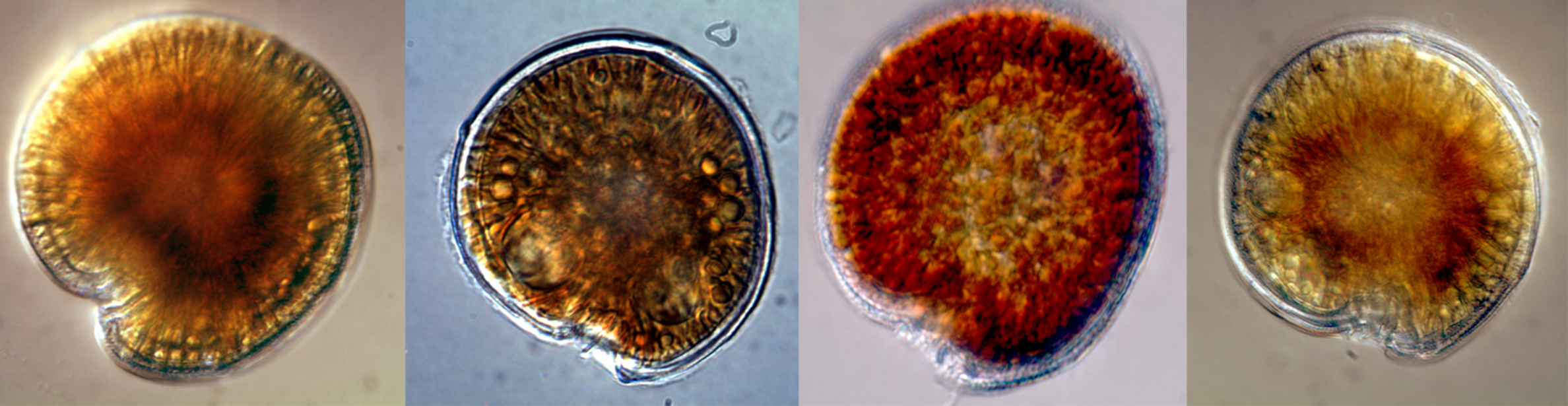

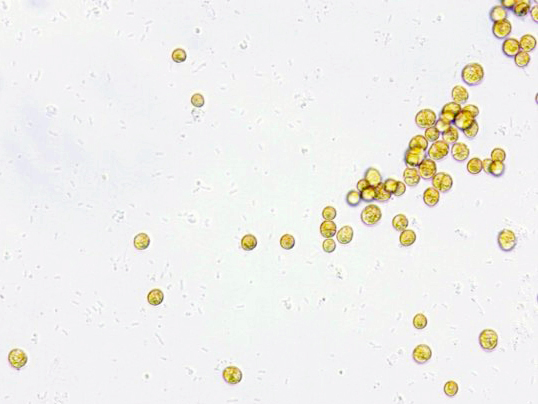

The dinoflagellate Karenia brevis.

Photo: Smithsonian Marine Station-Ft. Pierce FL

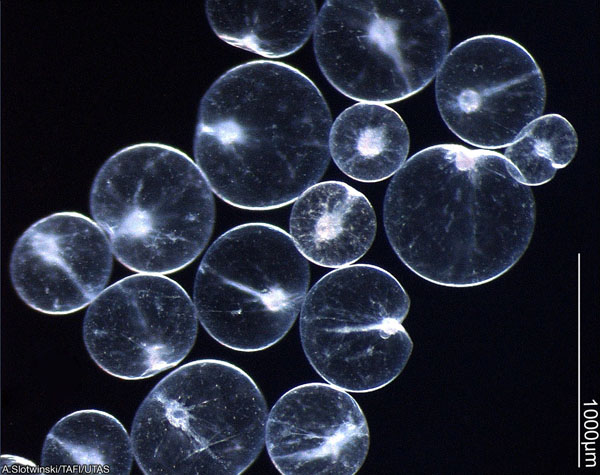

Noctiluca scitillans is another dinoflagellate that locals may know about – but did know they were dinoflagellates. What you may know it for is its ability to produce bioluminescence – “light in the sea” – what many locals called “phosphorus” when I was a kid. When disturbed a chemical reaction will create a blueish colored light. We see it during warm summer evenings when we walk through the water – or our footprints in the sand. From a boat you can see the blue light as fish swim by, or the wake from the moving boat. I remember once in high school we did a night dive near a pier where the bioluminescence from these dinoflagellates was so bright that you could see other divers, fish, and the pier without a dive light. Jim Lovell, commander of Apollo 13, tells the story of a night bombing mission he participated during the Korean War where his navigation lights went out on the return trip. The carrier was running without lights to avoid detection, but Lovell found the ship by the bioluminescent trail left by the propeller churning these dinoflagellates. This dinoflagellate is found all over the world.

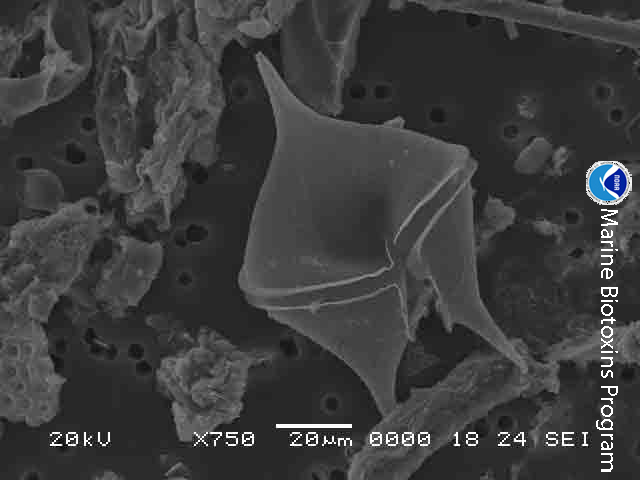

Noctiluca are one of the dinoflagellates that produce bioluminescence.

Photo: University of New Hampshire.

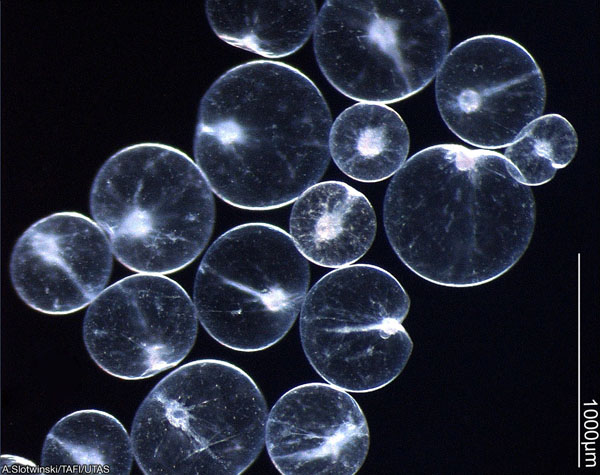

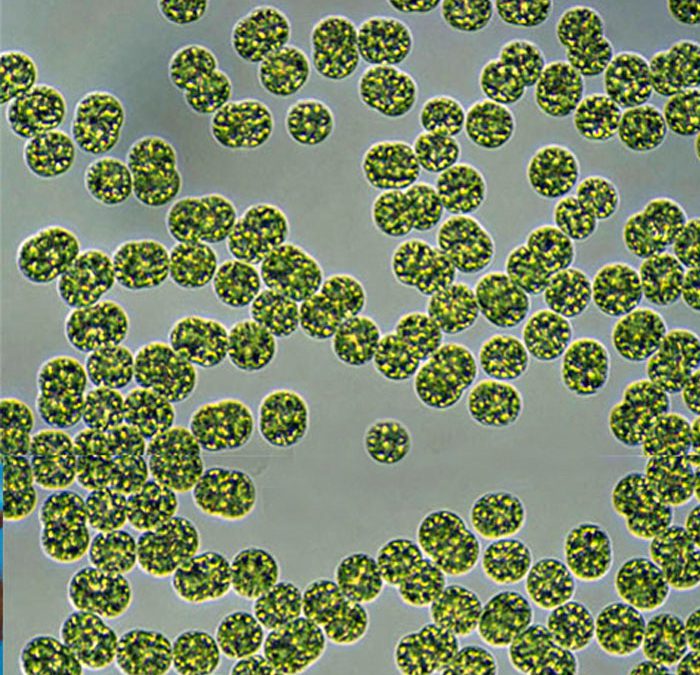

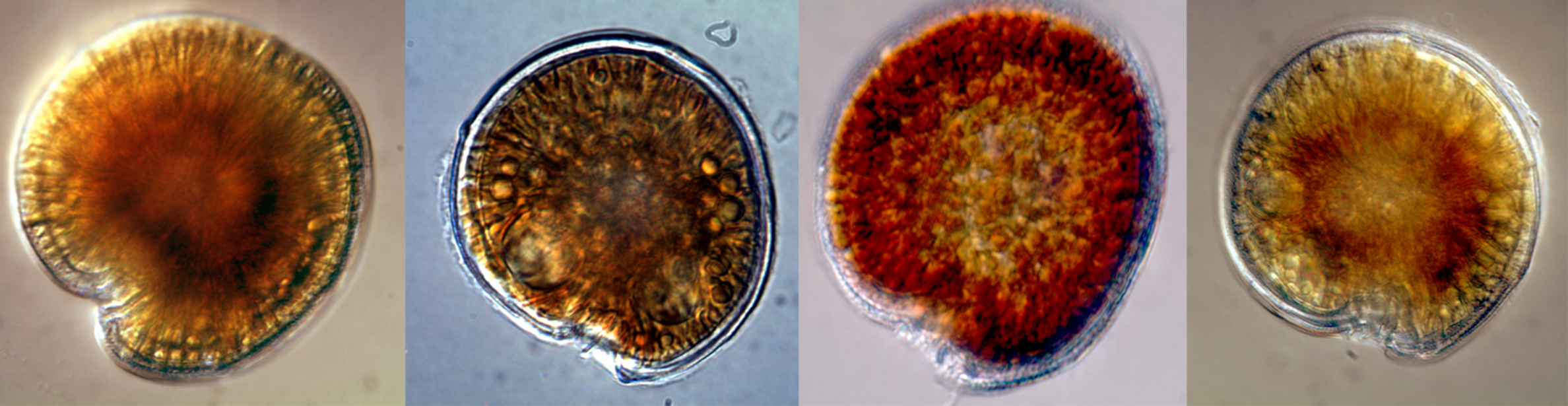

Zooxanthalle is a dinoflagellate you may not have heard of, but you may have heard of the coral bleaching that is occurring on reefs across the world. Corals are actually jellyfish and their tissue, like many jellyfish, is clear. The bright colors we are familiar with are caused by a symbiotic dinoflagellate that lives within the tissue of the corals. This symbiotic dinoflagellate is a group of several species known as zooxanthalle. In this partnership the photosynthetic zooxanthalle use waste products from the coral, and the sun, to photosynthesize. The products of photosynthesis are used to produce sugars, proteins, and other material that both the corals and the zooxanthalle need. Because of the need for sunlight, reefs usually occur in very clear – nutrient poor – waters. The bleaching we may be familiar with is caused when the reef is exposed to stress – high temperatures, pollutants, etc. and the zooxanthalle are expelled along with their photosynthetic pigments (the colors) – leaving only the clear tissue of the coral and a “white” appearance in color – bleaching.

These symbiotic zooxanthalle cells are the ones that give corals their color.

Image: NOAA

There are at least 18 species of dinoflagellates in the genus Gambierdiscus. These are not free-floating dinoflagellates, but ones they live on the bottom. You may not know them by name, but you may know them from the toxins they release when stressed – ciguatoxin. Ciguatoxins are a type of neurotoxin that can cause several illness – even death – in humans. The concentrations of ciguatoxin at the cellular level are minor and do not cause problems. However, as organisms graze on these dinoflagellates the toxins are not expelled from their bodies but are rather stored in the tissue. As you move up the food chain, no creature expels the toxins, and the concentrations increase in a process known as bioaccumulation. For humans the danger lies in eating the top predators in the food chain where the concentrations of ciguatoxin are high enough to cause problems – a condition known as ciguatera. Many who have visited the tropical parts of the world – where Gambierdiscus is most common – may have heard “you should not eat the barracuda” – or other large predators caught on a reef.

This situation has not historically been an issue for the northern Gulf of Mexico, but there are now records of this dinoflagellate north of the Florida Keys – as far north as North Carolina along the east coast. Scientists are watching the movement of this tropical group of dinoflagellates as the oceans warm.

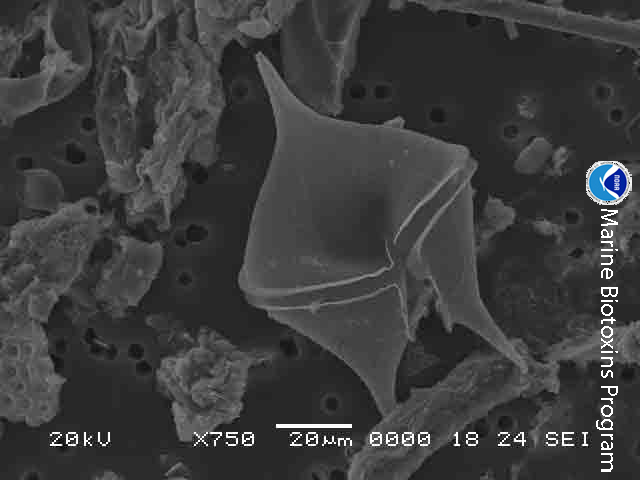

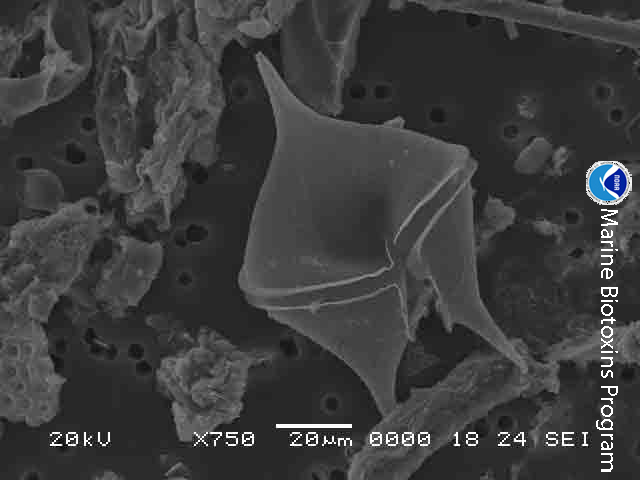

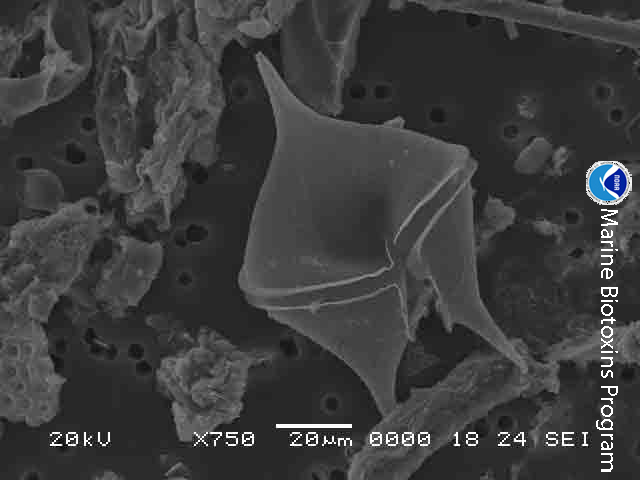

The dinoflagellate known as Gambierdiscus. Known to cause ciguatera.

Image: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

There are thousands more species of dinoflagellates in the Gulf, and know they play many important roles in the ecology of our marine environment.

Resources

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

National Institute of Health (NIH).

by Rick O'Connor | Nov 8, 2024

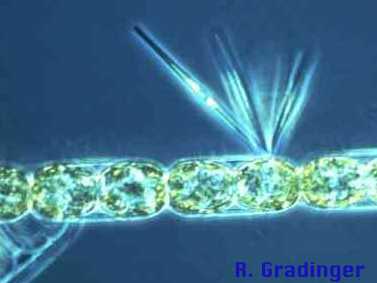

Remaining in the world of the microscopic, in this article we look at small plant-like creatures called diatoms. Diatoms are single celled algae that float in the surface waters of the Gulf of Mexico in the billions. Being plant-like, they possess chlorophyll for photosynthesis. In fact, they possess two forms of chlorophyll, and another photosynthetic pigment called fucoxanthin. Chlorophyll gives plants their characteristic green color, fucoxanthins are more yellow in color and give the diatoms the common name green-yellow algae.

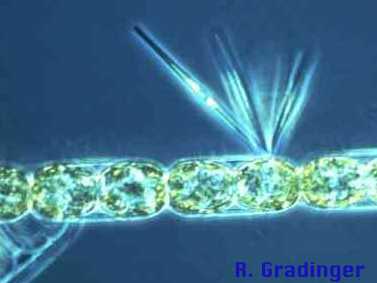

Silica covered diatoms.

Photo: NOAA

To collect them scientists pull what is called a plankton net. This net is funnel shaped with the diameter of the large opening being from several inches to several feet. The mesh is of a cloth material with extremely small holes to allow water to pass but not the plankton. The plankton net is deployed off the stern of the ship/boat and towed slowly at a specific depth. Once back on board the sample can be observed in a microscope.

Plankton net.

Photo: NOAA

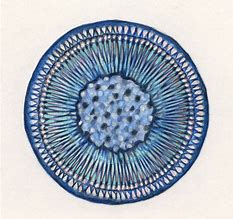

Diatoms are one of the more abundant microscopic plant-like algae called phytoplankton. They differ from other phytoplankters in that they do have the yellow-green color to them, but they also possess a clear glass-like shell called a frustule. This frustule is made of silica and comes in two parts. The top half is called the epitheca and the bottom half the hypotheca. The two halves fit together like the two plates of a petri dish. This frustule often has spines extending from it giving the diatom the appearance of a snowflake – and under the microscope they are beautiful. These spines actually serve a purpose. It is important they remain near the sunlit surface. To reduce sinking, these spines increase their surface area creating drag and reducing the chance they will sink. Most also produce gas pockets within the cytoplasm to make them more buoyant.

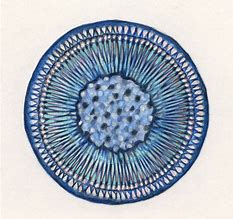

The spherical shape of the centric diatom.

Image: Florida International University

All diatoms are subdivided into two groups based on their frustule shape. Some have circular frustules and are called centric diatoms. Others are more elongated and are called pennate diatoms. Scientists currently estimate there are between 100,000 and 200,000 species of them. Though they are abundant in all the world’s oceans, they seem to be more abundant in cooler waters.

To say they play an important role in ocean ecology is an understatement. Between them and their other phytoplanktonic cousins – phytoplankton produce about 50% of the world’s oxygen. In an open ocean environment like the Gulf of Mexico where the seafloor is beyond the reach of the sun, diatoms, and other phytoplankton, are referred to as the “grasses of the sea”. They are the base of almost all marine creature’s food chain.

A phytoplankton bloom seen from space.

Photo: NOAA

When diatoms die (which is often in less than a week) their silica shells will eventually sink to the seafloor forming a layer of silica called “diatomaceous earth”. This sediment layer is commercially important as an abrasive. You will see diatomaceous earth labeled on toothpaste, household cleaners, soaps, anything with a little grit in it to help clean. It is also used in air and water filters to help purify such. You find these filters in aquariums, swimming pools, and hospitals.

If you collect a glass of water from the Gulf you are not going to see them without a microscope but know that the glass is full of these beautiful, amazing, and important marine creatures of the northern Gulf of Mexico.

by Rick O'Connor | Oct 25, 2024

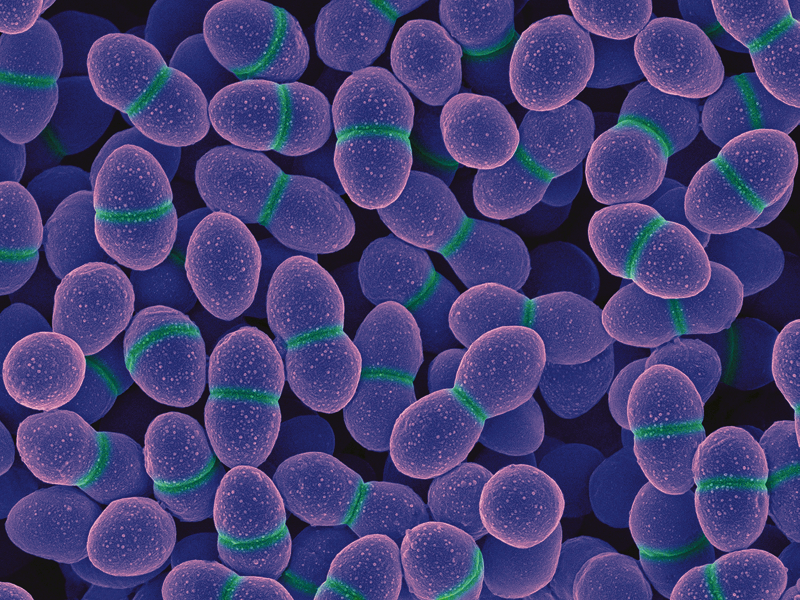

In the first article of this series, we discussed whether viruses were truly living organisms. Well, bacteria truly are. They possess all eight characteristics of life but differ from other forms of life in that they lack a true nucleus. Their genetic material just exists in the cytoplasm. This difference is large enough to place them in their own kingdom – Monera.

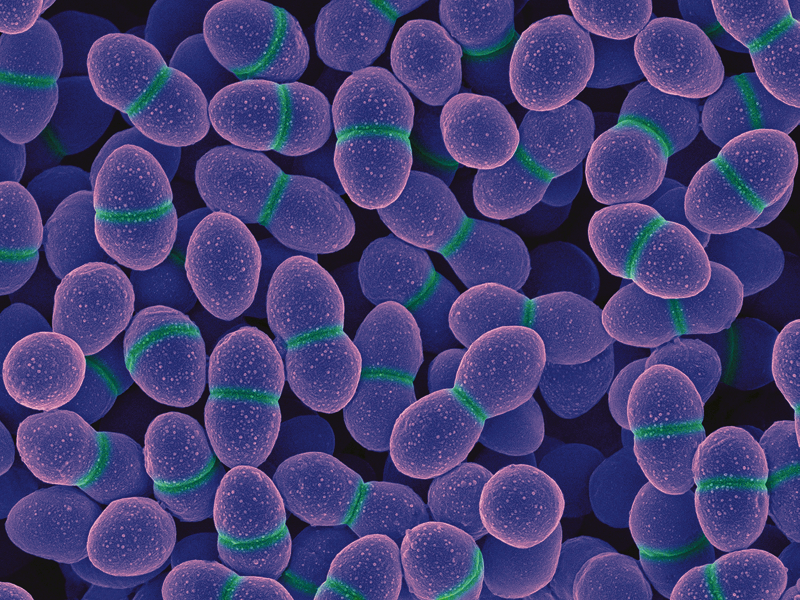

The spherical cells of the “coccus” bacteria Enterococcus.

Photo: National Institute of Health

Bacteria are single celled creatures, though some “hook” together to form long chains. A single cell will average between 5-10 microns in size. This is much larger than a virus but smaller than many eukaryotic cells (those that possess a nucleus).

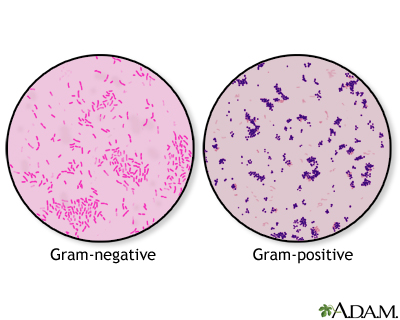

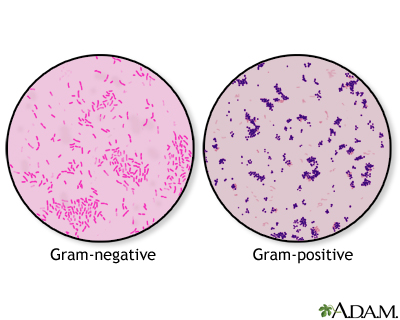

To further classify bacteria microbiologists will conduct a gram-stain test. Placing a cultured sample of bacteria on a slide, you “bath” them in what is called Gram-stain. Under the microscope the bacteria that appear “pink” are called gram negative, those that appear “purple” are gram positive. Thus, all bacteria can be quickly grouped into those that are gram negative and those that are gram positive.

After staining, gram negative bacteria appear pink in color; gram positive are purple.

Image: University of Florida

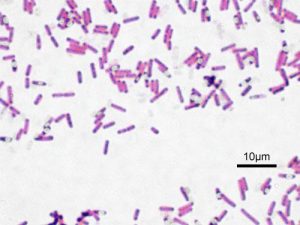

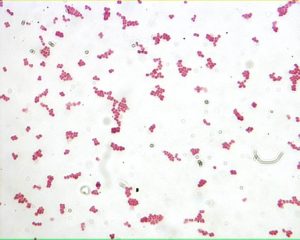

The next level of classification focuses on the shape of their cells. Those that are “rod-shaped” are called bacillus and often have the term in their name – such as Lactobacillus the bacteria found in milk that makes milk smell sour as their populations grow. The “sphere-shaped” bacteria are called coccus – such as Streptococcus (the bacterium that causes strep throat) and Enterococcus (the fecal bacterium used for monitoring water quality in marine waters). And the third group are “spiral-shaped” and are called spirillum – such as Campylobacter and Helicobacter both are human pathogens.

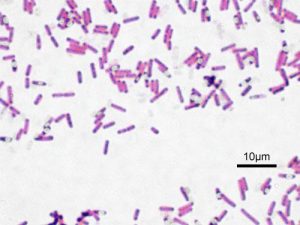

The rod-shaped bacterium known as bacillus.

Image: Wikipedia.

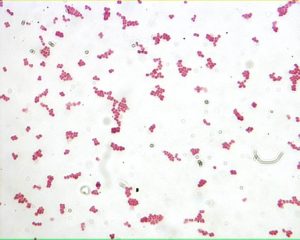

The bacterium known as coccus.

Image: Loyola University

The bacterium known as spirillum.

Image: Lake Superior College.

Bacteria are very abundant in the marine and estuarine waters of the Gulf of Mexico. They can be found floating in the water column, on the surface of the sediment, beneath the surface of the sediment, and on the bodies of marine organisms. When we think of bacteria we think of “dirty” conditions and disease, but many bacteria provide very important ecological benefits to the marine ecosystem and are “good” members of the community.

One important role some bacteria play is the conversion (“fixing”) of nutrients. Animals release toxic waste when they defecate and urinate. One of these is ammonia. Ammonia can bond with oxygen depleting the body of this needed element. Nitrogen fixing bacteria can convert toxic ammonia released into the environment into nitrite. Then another group of nitrogen fixing bacteria will convert nitrite into nitrate – a needed nutrient for plants, and eventually the entire food chain.

Some bacteria are excellent decomposers. When plants and animals die we say they “decay”. What is actually happening is the decomposing bacteria are converting nutrients in their bodies to forms that are usable by living organisms. One byproduct of this decomposition process is hydrogen sulfide – which smells like rotten eggs. In biologically productive ecosystems – like swamps and marshes – the smell of hydrogen sulfide is strong – often called “swamp gas”. It is the smell of nutrient conversion and much needed. Though in high concentrations, hydrogen sulfide is toxic as well – there needs to be a balance. We see this same process happenings when we compost food waste to form fertilizers for our gardens.

One place where the smell of sulfur is very strong is near volcanic vents. If you have been to Yellowstone, or a volcano, the smell is very evident. There are what are termed “extreme bacteria” who can live in these very hot, almost toxic, environments. Just as plants take water and carbon dioxide and convert this to sugar in the process of photosynthesis, bacteria can convert toxic forms of sulfur into usable carbohydrates for other living organisms. In the 1970s marine scientists discovered thermal vents on the bottom of the ocean. These hot “chimneys” spew black clouds of smoke into the water column. Approaching these chimneys carefully they found water temperatures between 700-800°F! Living close to these chimneys they found communities of worms, shrimps, fish, and crabs. The walls of the chimneys are actually composed of sulfur fixing bacteria that are converting volcanic minerals and compounds into sugars in a process called chemosynthesis – which supports these deep-sea communities.

The black smokers – hydrothermal vents – found on the ocean floor.

Photo: Woodshole Oceanographic Institute.

Of course, there are more familiar forms of bacteria that cause disease. Called pathogens – they can be problems for all marine life and sometimes humans. Fecal bacteria associated with human waste are not toxic in themselves at low concentrations. However, if their numbers increase (due to a sewage spill, etc.) these, and other possible pathogenic human bacteria, can be a human health issue. The Florida Department of Health monitors the fecal bacteria levels weekly at beaches where humans like to swim. High concentrations will require the department to issue health advisories. We know that all sorts of bacteria begin to replicate quickly in warmer conditions. This can be a problem with seafood that is not kept cold enough before serving. There are federal regulations on what temperatures commercially harvested seafood must be kept in order to be served or sold to the public. Federal and state agencies can monitor the temperatures of stored seafood as it moves from the fishing vessel to the table. But they cannot monitor it from your fishing rod to your table – that responsibility will fall on you. Pathogenic bacteria is the primary reason we refrigerate and/or freeze much of our food.

Closed due to bacteria.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Though bacteria in general have a bad name, many species are not harmful to us and are a major player in the health of our estuarine and marine communities.

by Rick O'Connor | Oct 18, 2024

We are going to begin this series of articles with a “creature” that some do not consider alive – viruses. While studying marine science in college, and my early days as a marine science educator, there was a debate as to whether viruses were actually alive and should be included in a biology course. A quick glance at the textbooks of the time shows they were often omitted – though they were included in my microbiology class. Why were they omitted? Why did some consider them “non-living creatures”?

The coronavirus next to a strand of DNA.

Image: Florida International University.

Well, we always began biology 101 with the characteristics of life. Let’s scan these characteristics and see where viruses fit.

- Made of cells. This is not the case for viruses. A typical cell will include a cell membrane filled with cytoplasm and a nucleus, which is filled with genetic material (chromosomes containing DNA and RNA). An examination of a virus you will find it is either DNA or RNA encapsulated in a protein coat. It is “nucleus-like” in nature. Most cells run between 10-20 microns in size. A typical nucleus within a mammal cell will run between 5-10 microns. A typical virus would be 0.1 microns – these are tiny things – MUCH smaller than a cell.

- Process energy. Nope – they do not. Most cells utilize energy during their metabolism. Viruses do not do this.

- Growth and development. Nope again. They “spread”, which we discuss in a moment, but they do not grow. We are now 0-3.

- Homeostasis. Homeostasis is the movement of material and environmental control to remain stable – and viruses do not do this.

- Respond to stimuli. Yes… here is one they do. Studies show that viruses do respond to their chemical and physical environment.

- Metabolism. As mentioned above, this would be a no.

- Adaptation. Studies show that through very rapid reproduction they can adapt to the changing environment they are in.

- Reproduce. This is a sort of “yes/no” answer. They do reproduce (as we say – “spread”) but they do not do this on their own. They invade the nucleus within the cells of their host and replace their genetic material with that of the host creature. Then, during cell replication within the host, new viruses are produced and “spread”.

So, you can see why there is a debate. Of the eight common characteristics of life, viruses possess only three – and one of those can only be achieved with the assistance of a host creature. Now the question would be – do be labeled as a “creature” do you need ALL eight characteristics of life? Or only a few? And if only a few – how many? Because of this most biologists do not consider them alive.

During one class when we were discussing this a student made a comment – “don’t we KILL viruses? If so, then it must be alive first”. Point taken – and we should understand the phrase “kill a viruses” does not mean literally killing. It is a phrase we use. Though some argue we do kill viruses and thus…

Another point we could make here is that all life on the planet has been classified using a system developed by the Swedish botanist Carlos Linnaeus. Each creature is placed in a kingdom, then phylum, class, order, family, genus, and eventually a species name is given. We “name” the creature using its genus and species name – Homo sapiens for example. We do not see this for viruses.

All that said, both the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the National Institute of Health indicate the “most common form of life in the sea are viral-like particles” – with over 10 million in a single drop of seawater. We will leave the debate here. Your thoughts?

by Laura Tiu | Sep 13, 2024

Western Dune Lake Tour

Walton County in the Florida Panhandle has 26 miles of coastline dotted with 15 named coastal dune lakes. Coastal dune lakes are technically permanent bodies of water found within 2 miles of the coast. However, the Walton County dune lakes are a unique geographical feature found only in Madagascar, Australia, New Zealand, Oregon, and here in Walton County.

What makes these lakes unique is that they have an intermittent connection with the Gulf of Mexico through an outfall where Gulf water and freshwater flow back and forth depending on rainfall, storm surge and tides. This causes the water salinity of the lakes to vary significantly from fresh to saline depending on which way the water is flowing. This diverse and distinctive environment hosts many plants and animals unique to this habitat.

There are several ways to enjoy our Coastal Dune Lakes for recreation. Activities include stand up paddle boarding, kayaking, or canoeing on the lakes located in State Parks. The lakes are popular birding and fishing spots and some offer nearby hiking trails.

The state park provides kayaks for exploring the dune lake at Topsail. It can be reached by hiking or a tram they provide.

Walton County has a county-led program to protect our coastal dune lakes. The Coastal Dune Lakes Advisory Board meets to discuss the county’s efforts to preserve the lakes and publicize the unique biological systems the lakes provide. Each year they sponsor events during October, Dune Lake Awareness month. This year, the Walton County Extension Office is hosting a Dune Lake Tour on October 17th. Registration will be available on Eventbrite starting September 17th. You can check out the Walton County Extension Facebook page for additional information.