by Laura Tiu | Sep 9, 2021

A Lionfish Removal and Awareness Day festival volunteer sorts lionfish for weighing. (L. Tiu)

The northwest Florida area has been identified as having the highest concentration of invasive lionfish in the world. Lionfish pose a significant threat to our native wildlife and habitat with spearfishing the primary means of control. Lionfish tournaments are one way to increase harvest of these invaders and help keep populations down. Not only that, but lionfish are a delicious tasting fish and tournaments help supply the local seafood markets with this unique offering.

Since 2019, Destin, Florida has been the site of the Emerald Coast Open (ECO), the largest lionfish tournament in the world, hosted by Destin-Fort Walton Beach and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission (FWC). While the tournament was canceled in 2020, due to the pandemic, the 2021 tournament and the Lionfish Removal and Awareness Day festival returned to the Destin Harbor May 14-16 with over 145 tournament participants from around Florida, the US, and even Canada. The windy weekend facilitated some sporty conditions keeping boats and teams from maximizing their time on the water, but ultimately 2,505 lionfish were removed during the pre-tournament and 7,745 lionfish were removed during the two-day event for a total of 10,250 invasive lionfish removed. Florida Sea Grant and FWC recruited over 50 volunteers from organizations such as Reef Environmental Education Foundation, Navarre Beach Marine Science Station and Tampa Bay Watch Discovery Center to man the tournament and surrounding festival.

Lionfish hunters competed for over $48,000 in cash prizes and $25,000 in gear prizes. Florida Man, a Destin-based dive charter on the DreadKnot, won $10,000 for harvesting the most lionfish, 1,371, in 2 days. Team Bottom Time secured the largest lionfish prize of $5,000 with a 17.32 inch fish. Team Into the Clouds wrapped up the $5,000 prize for smallest lionfish with a 1.61 inch fish, the smallest lionfish caught in Emerald Coast Open History.

It is never too early to start preparing for the 2022 tournament. For more information, visit EmeraldCoastOpen.com or Facebook.com/EmeraldCoastOpen. For information about Lionfish Removal and Awareness Day, visit FWCReefRangers.com

“An Equal Opportunity Institution”

by Laura Tiu | Mar 6, 2019

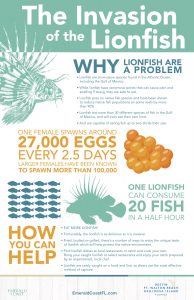

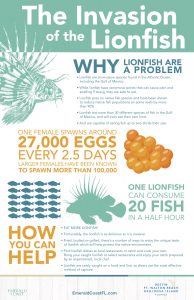

The northwest Florida area has been identified as having the highest concentration of invasive lionfish in the world. Lionfish pose a significant threat to our native wildlife and habitat with spearfishing the primary means of control. Lionfish tournaments are one way to increase harvest of these invaders and help keep populations down.

Located in Destin FL, and hosted by the Gulf Coast Lionfish Tournaments and the Emerald Coast Convention and Visitors Bureau, the Emerald Coast Open (ECO) is projected to be the largest lionfish tournament in history. The ECO, with large cash payouts, more gear and other prizes, and better competition, will attract professional and recreational divers, lionfish hunters and the general public.

You do not need to be on a team, or shoot hundreds of lionfish to win. Get rewarded for doing your part! The task is simple, remove lionfish and win cash and prizes! The pretournament runs from February 1 through May 15 with final weigh-in dockside at AJ’s Seafood and Oyster Bar on Destin Harbor May 16-19. Entry Fee is $75 per participant through April 1, 2019. After April 1, 2019, the entry fee is $100 per participant. You can learn more at the website http://emeraldcoastopen.com/, or follow the Tournament on Facebook.

The Emerald Coast Open will be held in conjunction with FWC’s Lionfish Removal & Awareness Day Festival (LRAD), May 18-19 at AJ’s and HarborWalk Village in Destin. The Festival will be held 10 a.m. to 5 p.m each day. Bring your friends and family for an amazing festival and learn about lionfish, taste lionfish, check out lionfish products! There will be many family-friendly activities including art, diving and marine conservation booths. Learn how to safely fillet a lionfish and try a lionfish dish at a local restaurant. Have fun listening to live music and watching the Tournament weigh-in and awards. Learn why lionfish are such a big problem and what you can do to help! Follow the Festival on Facebook!

“An Equal Opportunity Institution”

by Rick O'Connor | Mar 6, 2019

The vast majority of you reading this are aware of the lionfish, but for those who are not, this is a non-native invasive fish that has caused great concern within the economic and environmental communities. Lionfish were first reported in the waters off southeast Florida in the late 1980s. They dispersed north along the east coast of the state, over to Bermuda, throughout the Caribbean, and were first reported here in the northern Gulf of Mexico in 2010. It has been reported as the greatest invasion of an invasive species ever. In 2014, it was also reported that the highest densities of lionfish within the south Atlantic region were right here in the northern Gulf.

Lionfish at Pensacola Beach Snorkel Reef. Photo Credit: Robert Turpin

The creature is a voracious predator, consuming at least 70 species of small reef fish. For what ever reason, they prefer artificial reefs over natural ones and studies show that red snapper are further away, and higher above, artificial reefs that lionfish inhabit. All of this points to an economic and environmental problem with native fisheries in area waters.

So, what has been going on with lionfish in recent years?

What is the new science?

In 2018 Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission held its second statewide lionfish summit, and in 2019 Sea Grant held a panhandle regional lionfish workshop to get answers to these questions. There were sessions on recent research, impacts of the commercial harvest, and current regulations on harvesting the animals.

From the researchers we heard that the densities in the northern Gulf of Mexico have decreased over the last five years, at least in the shallow waters less than 120 feet. This is most probably due to the heavy harvest efforts from locals and from tournaments. They found that lionfish still prefer artificial over natural reefs but that their overall body condition on artificial reefs is poorer than those found on natural bottom. They have found evidence of some consumption of juvenile red snapper, but juvenile vermillion snapper have become a favorite. Another interesting discovery, they are feeding on other lionfish. Consumed lionfish are not as common as other species, but it is happening. They are also finding lionfish with ulcers on the skin. They are not sure of the cause, or whether this is impacting their population, but they will continue to study.

Deep water lionfish traps being tested by the University of Florida offshore Destin, FL. [ALEX FOGG/CONTRIBUTED PHOTO]

Can traps be found easily?

Will tethered buoys impact migrating species in the area?

Will the traps move between time of deployment and recovery?

How much by-catch will they harvest?

These are all concerns but there was some good news. Several different designs have been tried but one in particular, being studied by NOAA and the University of Florida, has had some success. The trap unfolds as hits the bottom, stays in the same location (even during recent storms), and only has about 10% by-catch – 90% of what it catches is lionfish. These traps are un-baited as well, using structure to attract them. However, these were not tethered to buoys (so there are questions there) and there is a larger issue… federal regulations.

Currently trapping for finfish in federal waters (9 miles out) is illegal in the Gulf of Mexico. Another issue is based on the Magnuson Act, all commercial harvest in federal waters needs to be sustainable. You cannot overharvest your target species, which is exactly what we want to do with lionfish. So, these regulatory hurdles will have to be dealt with before deep-water commercial harvest with traps could begin.

Harvested lionfish. Photo Credit: Bryan Clark

The current method of commercial harvest is with spearfishing SCUBA divers. The sale of salt water products license to do so soared between 2014 and 2016, but since there has been a declined. At the recent workshop the commercial harvesters and restaurants were there to discuss this problem.

First, the divers feel they need to be paid more in order to cover the cost of their harvest. This has become even harder in lieu of the decline in shallow, safe diving depth, waters. However, the restaurants feel the price needs to drop in order for them to offer the dish at a reasonable price to their customers. Most of the commercially harvested fish are currently going to markets outside the area where the current price is acceptable. The workshop suggested that this trend will probably continue and fewer harvesters will stay in the business. That said, the dive charters indicated they are making money taking charters out to specifically shoot lionfish for private consumption. This venture will probably increase.

So, after 10 years of lionfish in local waters, it appears that we have made a dent in their shallow water populations but must keep the pressure on. Several researchers indicated that frequent removals do make an impact, but infrequent does little – so the pressure needs to stay on. Deep water populations… we will have to see where the trap story goes.

If you have further questions on the current state of lionfish in our area, contact me at the Escambia County Extension Office. (850) 475-5230 ext. 111.

by Laura Tiu | Aug 3, 2018

Written By: Laura Tiu, Holden Harris, and Alexander Fogg

Non-containment lionfish traps being tested by the University of Florida offshore Destin, FL. Invasive lionfish are attracted to the lattice structure, then captured by netting when the trap is pulled from the sea floor. The trap may have the potential to control lionfish densities at depths not accessible by SCUBA divers. [ALEX FOGG/CONTRIBUTED PHOTO]

Red lionfish (Pterois volitas / P. miles) are a popular aquarium fish with striking red and white strips and graceful, butterfly-like fins. Native to the Indo-Pacific region, lionfish were introduced into the wild in the mid-1980s, likely from the release of pet lionfish into the coastal waters of SE Florida. In the early 2000s lionfish spread throughout the US eastern seaboard and into the Caribbean, before reaching the northern Gulf of Mexico in 2010. Today, lionfish densities in the northern Gulf are higher than anywhere else in their invaded range.

Invasive lionfish negatively affect native reef communities. They consume and compete with native reef fish, including economically important snappers and groupers. Their presence has shown to drive declines in native species and diversity. Lionfish possess 18 venomous spines that appear to deter native predators. The interaction of invasive lionfish with other reef stressors – including ocean acidification, overfishing, and pollution – is of concern to scientists.

Lionfish harvest by recreational and commercial divers is currently the best means of controlling their densities and minimizing their ecological impacts. Lionfish specific spearfishing tournaments have proven successful in removing large amounts in a relatively short amount of time. This year’s Lionfish Removal and Awareness Day removed almost 15,000 lionfish from the Northwest Florida waters in just two days. Lionfish is considered to be an excellent quality seafood, and they are now being targeted by a handful of commercial divers. Several Florida restaurants, seafood markets, and grocery stores chains are now regularly serving lionfish.

While diver removals can control localized lionfish densities, the problem is that lionfish also inhabit reefs much deeper than those that can be accessed by SCUBA divers. Surveys of deepwater reefs show lionfish have higher densities and larger body sizes than lionfish on shallower reefs. In the Gulf of Mexico, the highest densities of lionfish surveyed were between 150 – 300 feet. While SCUBA diving is typically limited to less than 130 feet, lionfish have been observed deeper than 1000 feet.

For the past several years, researchers have been working to develop a trap that may be able to harvest lionfish from deep water. Dr. Steve Gittings, Chief Scientist for the Office of National Marine Sanctuaries at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, has spearheaded the design for a “non-containment” lionfish trap. The design works to “bait” lionfish by offering a structure that attracts them. The trap remains open while deployed on the sea floor, allowing fish to move in and out of the trap footprint. When the trap is retrieved, a netting is pulled up around

Deep water lionfish traps being tested by the University of Florida offshore Destin, FL. [ALEX FOGG/CONTRIBUTED PHOTO]

The researchers are headed offshore to retrieve, redeploy, and collect data on the lionfish traps. Twelve non-containment traps are currently being tested offshore NW Florida. The research is supported by a grant from the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. The study will try to answer important questions for a new method of catching lionfish: where and how can the traps be most effective? How long should they be deployed? And, is there any bycatch (accidental catch of other species)?

Recent trials have proved successful in attracting lionfish to the trap with minimal bycatch. Continued research will hone the trap design and assess how deployment and retrieval methods may increase their effectiveness. If successful in testing, lionfish traps may become permitted for use by commercial and recreational fisherman. The traps could become a key tool in our quest to control this invasive species and may even generate income while protecting the deepwater environment.

Outreach and extension support for the UF’s lionfish trap research is provided by Florida Sea Grant. For more information contact Dr. Laura Tiu, Okaloosa and Walton Counties Sea Grant Extension Agent, at lgtiu@ufl.edu / 850-689-5850 (Okaloosa) / 850-892-8172 (Walton).

by Rick O'Connor | Sep 15, 2017

In the late 1980’s a few exotic lionfish were found off the coast of Dania Florida. I do not think anyone foresaw the impact this was going to have. Producing tens of thousands of drifting eggs per female each week, they began to disperse following the Gulf Stream. First in northeast Florida, then the Carolina’s, Bermuda, the Caribbean, and eventually the Gulf of Mexico. The invasion was one of the more dramatic ones seen in nature.

The Invasive Lionfish

Lionfish are found on a variety of structures, both natural and artificial, and are known from shallow estuaries to depths of 1000 feet in the ocean. They are opportunistic feeders, engulfing whatever is within their range and fits in their mouths, and have few predators due to their neurotoxicity spines. These fish are well-designed eating machines with a high reproductive rate, and perfectly adapted to invading new territories, if they can get there.

And they got here…

Like so many other invasive species, humans brought them to our state. Some arrive intentionally, some by accident, but we brought them. Lionfish came to Florida intentionally as an aquarium fish. Beautiful and exotic, they are popular at both public aquariums and with hobbyists… Then they escaped.

So what now?

What impact will these opportunistic fish have on the local environment? On the local economy?

This is, in essence, the definition of an invasive species. The potential for a negative impact on either the ecosystem or local fishing is there. We now know they are found on many local reefs, in many cases the dominant fish in the community. We know they can produce an average of 25,000 fertilized per female per week and breed most of the year. We also know they consume a variety of reef fish, about 70 species have been reported from their stomachs.

Over 70 species of small reef fish have been found in the stomachs of lionfish; including red snapper.

Photo: Bryan Clark

However, what impact is this having on local fisheries?

Well, we do know there have been more reports of fishermen catching them on hook and line. We also know that scientists are examining the DNA of their stomach content that cannot be identified visually, and some of the results indicate commercially valuable species are on the menu.

Area high school students are now conducting dissections using this same methodology. Under the direction of Dr. Jeff Eble, over 900 area high school students examined the stomach contents of local lionfish last year. Students from Escambia, Gulf Breeze, Navarre, Pensacola, Washington, and West Florida high schools – along with Woodlawn Middle School – identified 16 different species in lionfish stomachs. Of economic concern were snapper; 42% of the prey identified were Vermillion Snapper – 4% were Red Snapper.

Though the consumption of non-commercial species can affect the population of commercial ones, the direct consumption of commercial species is concerning. The commercial value of Vermillion Snapper landed in Escambia County in 2016 was about $800,000 (highest in the state).

This year two more high schools will participate in the dissection portion of this project; those being Tate and Pine Forest. These students need lionfish and we are seeking donations from local divers to help support this project. If interested in helping, please contact me at roc1@ufl.edu or (850) 475-5230.

References

Dahl, K.A. W.F. Patterson III. 2014. Habitat-Specific Density and Diet of Rapidly Expanding Invasive Red Lionfish (Pterois volitans), Populations in the Northern Gulf of Mexico. PLOS ONE. Vol 9 (8). Pp. 13.

FWC Commercial Landing Summaries. 2017. https://public.myfwc.com/FWRI/PFDM/ReportCreator.aspx.