by Rick O'Connor | Apr 14, 2017

The Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill was one of the worst natural disasters in our country’s history.

Photo: Gulf Sea Grant

We are pleased to announce the release of a pair of new bulletins outlining how the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill impacted the popular marine animals dolphins and sea turtles. To read these and other oil spill science publications, go to http://gulfseagrant.org/oilspilloutreach/publications/.

The Deepwater Horizon’s impact on bottlenose dolphins – In 2010, scientists documented a markedly increased number of stranded dolphins in the northern Gulf of Mexico. Was oil exposure to blame? Could other factors have been in play? Read the answers to these questions here: http://masgc.org/oilscience/oil-spill-science-dolphins.pdf.

Sea turtles and the Deepwater Horizon oil spill – This publication reviews the estimated damage oil exposure caused to sea turtles and discusses continued research and monitoring efforts for these already endangered and threatened species. Click here to read this bulletin: http://masgc.org/oilscience/oil-spill-science-sea-turtles.pdf.

Also –

“Sea turtles and oil spills” presentations – On March 23 in Brownsville, Texas, more than 100 participants gathered in person and online to listen to scientists, responders, and sea turtle specialists explain what we know about how these creatures fared in 2010 and detail ongoing conservation programs. Watch videos of the presentations here: http://gulfseagrant.org/sea-turtles-oil-spills/.

Our oil spill science outreach team hopes you will find these resources useful! J

by Andrea Albertin | Mar 11, 2017

Stormwater runoff is water from rainfall that flows along the land surface. This runoff usually finds its way into the nearest ditch or water body, such as a river, stream, lake or pond. Generally speaking, in natural undeveloped areas only 10% of rainfall is runoff. About 40% returns to the atmosphere though evapotranspiration, which is the water evaporated from land and plant surfaces plus water lost directly from plants to the atmosphere through their leaves. The remaining 50% of rainfall soaks into the ground, supporting vegetation, contributing to streamflow and replenishing groundwater resources. In Florida, where 90% of the population relies on groundwater for their drinking water, aquifer recharge from infiltrating rainwater is vital.

Stormwater runoff from a drainage pipe flowing into a creek.

Photo: Andrea Albertin

As landscapes become more developed, areas that use to absorb rainwater are replaced by impervious surfaces like rooftops, driveways, parking lots and roads. Additionally, we are levelling our land, removing natural depressions in the landscape that trap rainwater and give it time to seep back into the ground. As a result, a higher percentage of rainfall is becoming runoff and which flow at faster rates into storm drainages and nearby water bodies instead of soaking into the soil.

A major problem with stormwater runoff is that as it flows over surfaces, it picks up potential pollutants that end up in our waterways. These include trash, sediment, fertilizer and pesticides from lawns, bacteria from dog waste, metals from rooftops, and oil from parking lots and roads. Stormwater runoff is often the main cause of surface water pollution in urban areas.

Luckily, there are ways in which we can all help slow the flow and reduce stormwater runoff. These reductions can give rainfall more time to soak back into the ground and replenish our needed stores of groundwater.

What can you do to help “slow the flow” of stormwater?

The UF/IFAS Florida Friendly Landscaping Program provides the following recommendations that you, as a homeowner, can do to reduce stormwater runoff from your property:

- Direct your downspouts and gutters to drain onto the lawn, plant beds, or containment areas, so that rain soaks into the soil instead of running off the yard.

- Use mulch, bricks, flagstone, gravel, or other porous surfaces for walkways, patios, and drives.

- Reduce soil erosion by planting groundcovers on exposed soil such as under trees or on steep slopes

- Collect and store runoff from your roof in a rain barrel or cistern.

- Create swales (low areas), rain gardens or terracing on your property to catch, hold, and filter stormwater.

- Pick up after your pets.

- Clean up oil spills and leaks on the driveway. Instead of using soap and water, spread cat litter over oil, sweep it up and then throw away in the trash.

- Sweep grass clippings, fertilizer, and soil from driveways and streets back onto the lawn. Remove trash from street gutters before it washes into storm drains. The City of Tallahassee’s TAPP (Think About Personal Pollution) Campaign is another excellent resource for ways in which you can help reduce stormwater runoff (http://www.tappwater.org/).

- For more information on stormwater management on your property and other Florida Friendly Landscaping principles, you can visit the Florida Friendly Landscaping website at: https://ffl.ifas.ufl.edu.

TAPP also provides a manual for homeowners on how to build a raingarden, which can be found at http://tappwaterapp.com/what-can-i-do/build-a-rain-garden/. Raingardens are small depressions (either naturally occurring or created) that are planted with native plants. They are designed to temporarily catch rainwater, giving it time to slowly soak back into the ground.

Grass covered drainage ditches slow the flow of stormwater runoff and allow more rainwater to soak back into the ground.

Photo: Andrea Albertin

by Rick O'Connor | Jul 31, 2016

Most of us have heard about the toxic algal blooms plaguing south Florida waters. If not, check out http://www.cnbc.com/2016/07/05/. This bloom has caused several major fish kills, bad odors, and has kept tourist away from the area. What happen? and could it happen in the panhandle?

One of the many lock systems that controls water flow in Lake Okeechobee.

Photo: Florida Sea Grant

First we have to understand what happened in south Florida. The source of the problem is Lake Okeechobee. This large freshwater lake has been diked and channeled over the years to supply water to cities and farms in south Florida. The flow of water in and out of the lake is controlled by the Army Corp of Engineers. Typically, this time of year they manage the level of water within the lake to prepare for both the rainy and hurricane seasons. To do this they allow water to flow out into local rivers and canals. However, the water within the lake is heavy with nutrients. Fertilizers, leave matter, and animal waste are discharged into the lake from neighboring communities and agriculture fields. These nutrients fuel the rapid growth of plants and algae, which we call a bloom. These blooms can contain toxic forms of algae that can cause skin irritation and intestinal problems in humans, and can kill many forms of wildlife. Because the state is trying to restore the Everglades, lake water that test high for nutrients cannot be released in a southern direction but rather east and west towards the populated coasts.

But this year was different…

Due to heavy rainfall in spring the Corp had to release more water than they typically would. It was after this release that the large blooms along the east coast began to occur. The state declared a state of emergency and the flow of water out of the lake was altered. But for east Florida, the damage was done.

Could this happen in other parts of the state? Could it happen in the panhandle?

Well first, we have very few controlled water systems for drinking water (reservoirs) so that exact same scenario is a low probability. During a recent trip out west I camped several times along a reservoir designed to hold drinking water for municipalities. At each there were information signs warning swimmers about the potential of high levels of toxic cyanobacteria, particularly in late summer and early fall. But here most of our rivers flow unimpeded (relatively) to the Gulf of Mexico. Our drinking water instead comes from the ground.

But could our local waterways become contaminated with algae?

Yes…

With the situation going on in south Florida people of have pointed fingers at the Corp for releasing too much water. But because the water had high levels of nutrients, others have pointed the finger at the fact that we do not regulate nutrient discharge as well as we should. We have cities and farms here as well, and each produce and release nutrients in the form of leaf litter, animal waste, and fertilizers. Actually large fish kills have happened here. I remember seeing large masses of dead fish on the surface of Bayou Texar in Pensacola when I was younger; Bayou’s Chico and Grande had their problems as well. Most of these were due to excessive nutrients being released from developed areas in the local municipalities.

When I first joined Sea Grant I was told that water quality was a concern in the Pensacola area. Many remembered these large fish kills from a few decades ago and were still concerned about the quality of water in our area, particularly the bayous. I have worked with local non-profits, as well as state and county agencies, and the local high schools to monitor nutrients in the area. The nutrient of concern here is nitrogen. Several groups including the Bream Fishermen’s Association, Escambia County, UF/IFAS LAKEWATCH, and the School District’s Marine Science Academy routinely monitor for nitrogen. Others, such as the University of West Florida and the U.S. EPA, do so when they are working on such projects. Low nitrogen levels could mean less being discharged, but it could also mean that the algae have consumed it – so monitoring for chlorophyll (indicator for the presence of algae) is also important; and these groups do this as well. High levels of algae can trigger declines in dissolved oxygen, so this is monitored also. Low dissolved oxygen can trigger fish kills, and this data is collected by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. I try to collect as much of this data as I can and post it on our website each Friday on the Escambia County Extension website.

A large algal bloom in a south Florida waterway.

Photo: University of South Florida News

Yes, we have areas with relative high levels of nitrogen, when compared to other locations sampled. Dissolved oxygen levels are typically okay in the Pensacola Bay area, but most of the monitors are sampling in shallow water near shore. A UF/IFAS LAKEWATCH volunteer has recently started to monitor DO at depth in Perdido Bay. In the Pensacola Bay area, fish kills are down when compared to earlier decades.

2016 panhandle fish kills based on data from FWC

- Escambia/Santa Rosa Counties – 8 fish kills – 312 dead fish – cause for most is unknown

- Okaloosa/Walton – 12 fish kills – 1102 dead fish – cause for most is unknown

- Bay – 13 fish kills – 3092 dead fish – 3 of these were attributed to low DO – 2 in White Western Lake, 1 in Grand Lagoon

- Gulf – 5 fish kills – 719 dead fish – cause for most is in unknown – most were starfish

- Franklin – 1 dead sturgeon at St. Vincent Island

- Wakulla – 2 fish kills – 200 dead fish – cause was fishing net dump

- Jefferson – reported no fish kills so far this year.

There are fish kills occurring, the cause of most is unknown, but the numbers are much lower than they were a few decades ago and many are not related to the nutrient issue. However it is true that not all fish kills are reported to FWC. Many residents who discover one are not sure who to call or where to report. If you do discover a fish kill you can report it to the FWC at http://myfwc.com/research/saltwater/health/fish-kills-hotline/. We also experienced a large red tide event this past fall. Though red tides do occur naturally, and 2015 was an El Nino year with unusual rainfall patterns, they can be enhanced with increase nutrients in the run-off.

What we do have a problem with in many areas of the panhandle coast are health advisories. Some agencies, FDEP and Escambia County, monitor for fecal coliform bacteria locally. These are bacteria associated with the digestive system of birds and mammals, including humans, and are non-toxic. However, they are indicators that animal waste is in the water and that pathogenic bacteria associated with animals could be also. When samples are collected the number of bacteria colonies are counted. If the number is above what is allowed a re-sample is taken. If the second count is high as well a health advisory is issued. Many coastal waterways in the panhandle are fighting this problem. Based on FDEP data, the bayous of the Pensacola area average between 8-10 advisories each year. Not all bodies of water are monitored at the same frequency but our bayous are issued advisories between 25-35% of the time they are sampled. Most of the advisories occur after a heavy rainfall, suggesting the source of the animal waste is from run-off, but it could be related to leaky septic tanks systems as well.

So though the scenario that is occurring in south Florida is a low risk for our area, we do have some concerns and there are many things residents and citizens can do to help reduce the risk of a large problem occurring.

- Manage the amount of fertilizer you use. Whether you are a farmer, a lawn care company, or property owner, think about how much you are using and use only what your plants need. For assistance on this, contact your extension office.

- Reduce leaf litter from entering waterways. When raking we recommend you bag your leaves using the new paper bags. These can be composted at the landfill. If you have large amounts of leaves that cannot be bagged, consider composting yourself. The demonstration garden at your local extension office can show you several methods of composting.

- Pick up your animal waste. Our streets and parks are littered with pet waste that owners have not removed, even with the city and county providing plastic bag dispensers to do so. Please be aware of the problem with animal waste and help keep our streets and waterways clean.

- If you have a septic tank, maintain it properly. If you are not sure how to do this, contact your local extension office for advice.

If you have questions about local water quality issues, contact your local county extension office.

by Rick O'Connor | Oct 31, 2015

Many coastal Panhandlers woke up this week to the sight and smell of dead fish. Thousands of them washed ashore from Panama City to Pensacola. This mass die off included a variety of species including whiting, sheepshead, hake, cusk eels, and even lionfish; there were also reports of dead bass from the Dune Lakes in Walton and Okaloosa counties. What caused this mass die off of fish?

The suspect is red tide…

Most of us along the panhandle have heard of red tide but we may not know what it is or what causes it. Many attribute the red tide events to human impacts, stormwater runoff etc., but in fact they have been around for centuries. There are records suggesting that the European colonials experienced them and I have read one account that the Red Sea got its name from the frequency of these events there. So what is this “red tide” and what causes it?

Dead fish line the beaches of Panama City.

Photo: Randy Robinson

It is actually a bloom of small single celled plants called dinoflagellates. There are thousands of species of dinoflagellates in the world’s oceans and not all cause red tide, but there are several species that do. These small microscopic plants drift near the surface of the ocean acquiring sunlight to photosynthesize. They possess two small “hairs” called flagella (hence the name “dinoflagellate”) to help orient themselves in the water column. Most have a shell covering their body called a theca and some shells have small spines to increase their surface area to resist sinking. One method of defense found in some dinoflagellates is the production of light – bioluminescence. This light is produced by a chemical reaction triggered by the creature as a flash of blue – many locals refer to it as “phosphorus”. Other dinoflagellates instead will release a toxin… some of these are ones we call “red tide”.

Red tide organisms are always in the water column of marine environments but are usually in low concentrations, maybe 300-500 cells per milliliter of water. But under favorable conditions, warm water with nutrients, they multiple… sometimes in great numbers, such as 3000-5000 cells/ml, and we have a “bloom”. The number of cells within these blooms can be high enough that we can actually see the water change color… hence “red tide”.

The dinoflagellate Karenia brevis.

Photo: Smithsonian Marine Station-Ft. Pierce FL

The most common red tide dinoflagellate associated with the Gulf of Mexico is Karenia brevis. Karenia blooms typically form offshore and are of little impact to the coastal communities. However when the wind and tides are right these blooms will drift towards shore. When they do fish kills occur and humans have eye and throat irritations. Marine mammals in particular struggle with red tide. As the bloom comes near shore it reaches the bottom of the water column and many of the bottom dwelling fish suffer. Most of the photos of fish I saw in the October 2015 fish kill were bottom dwellers, including many invasive lionfish.

Is there anything we can do to prevent red tides?

Not really… Again, they are naturally occurring event. We may increase the frequency of the events by discharging excessive nutrients into the water from our run-off but they would probably occur anyway. Red tide events are not as common in the panhandle as they are in southwest Florida. The Gulf waters near Charlotte Harbor are shallow, warm, and near the many manicured lawns, gold courses, and the discharge of much of the agriculture in the state. Occasionally blooms formed in that part of the state drift north but this year a bloom formed off of Bay and Gulf counties in early October. The recent storm that passed through probably pushed the bloom inland and to the west. The biggest hazard of humans is eye, throat, and skin irritation. It is quite uncomfortable to be around these blooms. In 1996 a local bloom was concentrated enough that the campground at Ft. Pickens had to be closed. I was in Galveston Texas when I heard about the red tide occurring in the Florida panhandle. As I was leaving Galveston the newspaper reported the closer of all oyster harvesting in Texas due to a red tide generated in the Padre Island area and was moving north. Seems that red tide is covering a large portion of the Gulf coast the last week of October. That said… anything communities can do to reduce nutrient runoff will certain decrease the frequency of red tides.

The carcass of the invasive lionfish was part of the October red tide kill.

Photo: Shelly Marshall

The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission post red tide updates from around the state on their website and the Escambia County Extension Office post a local water quality update each Friday that has red tide information as well.

FWC

http://myfwc.com/research/redtide/

Escambia County Extension

http://escambia.ifas.ufl.edu

by Rick O'Connor | Sep 24, 2015

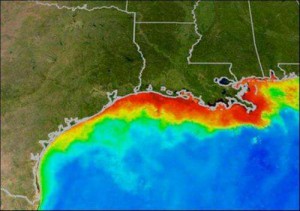

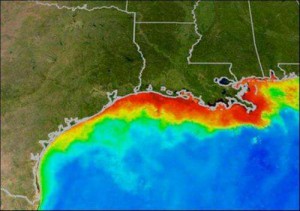

The red area indicates where dissolved oxygen levels are low.

I don’t want this to sound like a “Debbie Downer”… but there are problems with our estuaries and panhandle residents should be aware of them. There are things you can do to correct them – which we will discuss in the final issues of this series – but you need to understand the problem to be able to solve it. Unfortunately there are many issues and problems our bays and bayous face and we do not have time in this short article to discuss them all, but we will discuss some.

We’ll start at the top… with our rivers. Since the founding of our nation many communities were built on estuaries; those that were not were built on the rivers. Water was an easy way to move throughout the country – much easier than wagon crossing over the Appalachians or through a bog. There are several communities that developed along the rivers that feed the panhandle bays. Though the situation has improved in the last few decades, most of these communities have used these rivers as a place to dump their waste. Assorted chemicals, sewage, and solid waste were discharged… and it all came down to us. The Mississippi River is an example of this problem. Discovered in the 1990’s the Louisiana Dead Zone is an area in the Gulf where the levels of dissolved oxygen are so low that little or no life can be found on the ocean floor there. It is believed to be trigger by nutrients, chemical fertilizers and animal waste, being discharged upstream. These nutrients create a bloom of plankton, which can darken the water. Though the phytoplankton can produce oxygen during the daylight hours, they consume it in the evening, lowering the concentration of dissolved oxygen within the water column. The plankton are relatively short lived and eventually die. As the dead plankton fall out to the seafloor bacteria begin to decompose their bodies thus dropping the dissolved oxygen levels further. When the dissolved oxygen concentrations drop below 4.0 millgrams/liter we say the water is hypoxic (low in oxygen). Many species of aquatic organisms begin to stress. At 2.0 mg/L many species will die and we have a “dead zone”. If it reaches 0.0 mg/L we say the water is anoxic (without oxygen). This process is called eutrophication and not only a problem at the mouth of the Mississippi River, it occurs in almost all of the bays and bayous of the panhandle and is the primary cause of local fish kills.

A more recent issue with our rivers has been the reduction of water. In the so called “Water Wars” the state of Georgia has used its damn system to block the flow of the Chattahoochee River to create electricity and a reservoir of drinking water for river communities. Under normal conditions this has not created a problem however in recent years the southeast has experienced drought and the state of Georgia has had the need to hold back water for large communities – such as Atlanta. This has reduced the amount of water flowing towards the Gulf and has impacted communities all along the way. It is not the only issue but is the primary factor triggering the collapse of the oyster industry in Apalachicola. The reduced freshwater flow has increased salinities in the bay. This has disrupted the life cycle of the eastern oyster and has increased both predation and disease within these populations. Apalachicola produces over 90% of Florida’s oysters and 10% of the oysters for the entire country! Oysters are a huge industry in this town. Many are oystermen and many others process the product when it is landed… the industry is on the verge of collapsing. (Learn more).

Oysterman on Apalachicola Bay.

Photo: Sea Grant

These are just some the issues stemming from the rivers… what about the issues initiated from the communities that live along the bay…

How about the seafood? We discussed the oyster industry in Apalachicola Bay but oyster production in other local bays has declined as well (for other reasons). Scallops are gone from many of their historic estuaries, shrimp and blue crab landings are down, this year mullet seem to be hard to find. What is going on here? For the most part the decline in seafood products can be tied to either a decline in water quality or from over harvesting. The harvesting issue is easy… do not harvest as much. However these fisheries management decisions impact many lives and has caused a lot of debate. First you need to determine whether the decline is due to overharvesting or some other environmental factor… easier said than done. Certainly the biology of your target species will give you an idea of how many animals you can remove from the system and sustain a healthy population (maximum sustainable yield) but this method has triggered debate as well. Most fishermen do not want to see the fishery collapse and are willing to work with fishery managers to assure this – but they do have bills to pay. Fishery managers have a responsibility to assure the fishery remain for current and future generations of fishermen and they are basing their decisions on the best available science. It is a touchy subject for many and a problem within our estuaries.

The other cause of declining seafood is poor water quality. You can talk to any “ole timer” and they will tell you about the days when the water was clearer, the grass was thicker, and the fish were more abundant… what happen? I spoke with my father-in-law before he passed away about the changes he saw in Bayou Texar in Pensacola. He remembers being able to see the bottom, more seagrass, and being able to catch a variety of finfish as well as shrimp the size of your hand. The first change he remembered was a change in water clarity… it became murkier… and this happen about the time they began to develop the east side of the bayou. As our communities grew more land was cleared for development. The cleared land allowed more runoff to reach the creeks, bayous, and bays. Infrastructure had to be placed to reduce flooding of yards and streets – Bayou Texar has 38 storm drains. All of this led to more runoff into our water ways. With the increase in turbidity the amount of sunlight reaching the bottom was reduced and seagrasses began to decline. Many species of seagrass require salinities of 25 parts per thousand or higher and the increase in freshwater runoff lowered the salinity which also stressed these grasses. Much of this runoff included sand and silt and the grasses were basically buried. All in all seagrasses declined… and with them many of the marine creatures. Salt marshes were removed for coastal developments, industries were located on our rivers and bays and introduced their chemical discharge, and boating activity increased… our estuaries were being literally “loved to death”. I have seen in my lifetime the decline of sea urchins and scallops from our bay, the increase in turbidity, and the decline of seagrasses. But we cannot blame all of this on habitat loss and pollution. Speaking recently with fisheries managers they believe the recent decline in blue crab landings is due to drought. Reduction in rainfall means reduction in river discharge, which means an increase in salinity and a disruption of the crab reproductive cycle.

Power plant on one of the panhandle estuaries.

Photo: Flickr

Another problem that is associated with runoff has been the increase in bacteria. Fecal coliform bacteria are found in the stomachs of birds and mammals. They assist with our digestion and are released into the environment whenever we (or they) go to the bathroom. So finding fecal coliforms in the water is not unusual… the problem is TOO many fecal coliforms. As mentioned coliforms are not a threat to us but they are used as an indicator of how much waste is in the water. Feces harbors many other microbes in addition to coliforms – hepatitis and cholera outbreaks have been linked to sewage in the water. So agencies monitor for these each week. Most agencies will monitor for E. coli when sampling freshwater and Enterococcus in saline waters. E. coli values of 800 colonies / 100 milliters of sample or higher, and Enterococcus values of 104 colonies / 100 ml of sample will trigger a health advisory being issued – and some bodies of water being closed. In the Pensacola area the Florida Department of Environmental Protection and the Escambia County Health Department both monitor for bacteria. They post their results each week and I, in turn, post to the community. Our local bayous are averaging between 8-10 advisories each year. The problem with these advisories is that residents who live on the waterways, businesses (such as hotels and ecotours) who use the waterways become concerned about entering the water. It is not good for business or property values if the body of water you are on has high levels of bacteria and signs posting “no swimming”.

Closed due to bacteria.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

There are many problems our estuaries are facing but for this article we will end with solid waste. Trash and garbage has been a problem since I can remember. Campaigns have been launched each decade to try and reduce the problem but the problem still exist. Plastics and monofilament litter the beaches and waterways creating problems for marine life and an “eye soar” for those enjoying the bay. I am currently working with the Wildlife Sanctuary of Northwest Florida and CleanPeace to monitor solid waste in Pensacola Bay. Each week CleanPeace host a Saturday event they call “Ocean Hour” where they select a location on the bay and clean for an hour. They submit the top three items to me each week and have been doing this since January… it has been pretty consistent… cigarette butts, plastic food wrappers, and plastic drink containers. We are not going to get rid of garbage on our beaches but if we can consistently reduce the “top three” we should be able to reduce the problem.

More on what we can do to help in the final issue.