by Rick O'Connor | May 4, 2018

Humans have inhabited the shores of Pensacola Bay for centuries. Impacts on the ecology have happened all along, but the major impacts have occurred in the latter half of the 20th century. There has been an increase in human population, an increase in development, a decrease in water clarity, a decrease in seagrasses, and a decrease in the abundance of some marine organisms – like horseshoe crabs, scallops, and some marine fishes. There has also been an increase in inorganic and organic compounds from stormwater run-off, fish kills, and health advisories due excessive nutrients and fecal bacteria in local waters.

A view of Pensacola Bay from Santa Rosa Island.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Since the 1970’s, there have been efforts to help restore the health of the bay. Seagrasses have returned in some areas, fish kills have significantly reduced, and occasionally residents find scallops and horseshoe crabs – but there is still more to do. In this series of articles, I will present information provided in a recent publication (Lewis, et. al. 2016) and from citizen science monitoring. We will begin with an introduction to the bay itself.

The Pensacola Bay System is the fourth largest estuarine system in the state of Florida. The system includes Blackwater, Escambia, East, and Pensacola Bays. There are numerous smaller bayous, such as Indian, Mulat, and Hoffman, and three larger ones, which include Texar, Chico, and Grande. There are two lagoons that extend east and west of the pass. To the west is Big Lagoon and to the east is Santa Rosa Sound. The surface area of this bay system is about 144 mi2 and the coastline runs about 552 miles in length. There are four rivers that discharge into the system: the Escambia, Blackwater, Yellow, and East Rivers. The majority of watershed is in Alabama and covers about 7000 mi2. The mouth of the bay is located at the Pensacola Pass near Ft. Pickens and is 0.5 miles across. Depending on the source, the flush time for the entire bay has been reported between 18 and 200 days.

There are several ecosystems found within the bay system. Seagrasses are be found throughout the bay and bayous, but are more prevalent in Big Lagoon and Santa Rosa Sound. Oyster reefs have provided income for some in the East Bay area in the past, but production has declined in the last 50 years. Salt marshes are found throughout the bay as well, but the greatest acreage is in the Garcon area of Santa Rosa County. There are, of course, freshwater marshes near the mouths of the rivers with the largest being at the mouth of the Escambia River.

Members of the herring family are ones who are most often found during a fish kill triggered by hypoxia.

Photo: Madeline

Members of the drum family are one of the more common fishes found in the system and would include fish like the Spot and Atlantic Croaker. However, speckled trout, striped mullet, redfish, several species of flounder, have also been targets for local fishermen. Target fish include sardines, silversides, stingrays, pinfish, and killifish. Brown shrimp, oysters, and blue crab have historically provided a fishery for locals, but other invertebrates include several species of jellyfish, stone crabs, fiddler crabs, hermit crabs, grass shrimp, several species of snails, clams, bay squid, octopus, and even starfish. There is also a variety of benthic worms found within the sediments.

A finger of a salt marsh on Santa Rosa Island. The water here is saline, particularly during high tide. Photo: Rick O’Connor

There has been a decline in overall environmental quality since 1900 but, again, the biggest impacts have been between 1950 and 1970. Fish kills, a reduction in shrimp harvest, and hypoxia (a lack of dissolved oxygen) have all been problems.

In the articles to follow we will look deeper into specific environmental topics concerning the health of Pensacola Bay.

References

Lewis, M.J., J.T. Kirschenfeld, T. Goodhart. 2016. Environmental Quality of the Pensacola Bay System: Retrospective Review for Future Resource Management and Rehabilitation. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Gulf Breeze FL. EPA/600/R-16/169.

by Andrea Albertin | May 4, 2018

Special care needs to be taken with a septic system after a flood or heavy rains. Photo credit: Flooding in Deltona, FL after Hurricane Irma. P. Lynch/FEMA

Approximately 30% of Florida’s population relies on septic systems, or onsite sewage treatment and disposal systems (OSTDS), to treat and dispose of household wastewater. This includes all water from bathrooms and kitchens, and laundry machines.

When properly maintained, septic systems can last 25-30 years, and maintenance costs are relatively low. In a nutshell, the most important things you can do to maintain your system is to make sure nothing but toilet paper is flushed down toilets, reduce the amount of oils and fats that go down your kitchen sink, and have the system pumped every 3-5 years, depending on the size of your tank and number of people in your household.

During floods or heavy rains, the soil around the septic tank and in the drain field become saturated, or water-logged, and the effluent from the septic tank can’t properly drain though the soil. Special care needs to be taken with your septic system during and after a flood or heavy rains.

Image credit: wfeiden CC by SA 2.0

How does a traditional septic system work?

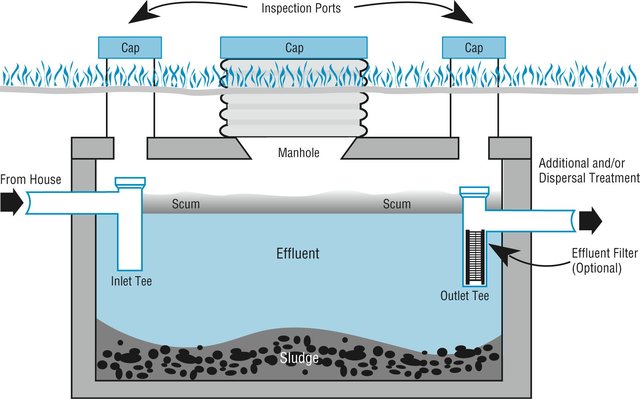

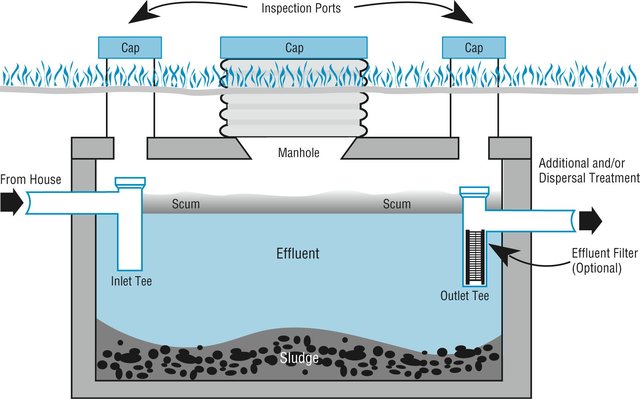

The most common type of OSTDS is a conventional septic system, made up of (1) a septic tank (above), which is a watertight container buried in the ground and (2) a drain field, or leach field. The effluent (liquid wastewater) from the tank flows into the drain field, which is usually a series of buried perforated pipes. The septic tank’s job is to separate out solids (which settle on the bottom as sludge), from oils and grease, which float to the top and form a scum layer. Bacteria break down the solids (the organic matter) in the tank. The effluent, which is in the middle layer of the tank, flows out of the tank and into the drain field where it then percolates down through the ground.

During floods or heavy rains, the soil around the septic tank and in the drain field become saturated, or water-logged, and the effluent from the septic tank can’t properly drain though the soil. Special care needs to be taken with your septic system during and after a flood or heavy rains.

What should you do after flooding occurs?

- Relieve pressure on the septic system by using it less or not at all until floodwaters recede and the soil has drained. For your septic system to work properly, water needs to drain freely in the drain field. Under flooded conditions, water can’t drain properly and can back up in your system. Remember that in most homes all water sent down the pipes goes into the septic system. Clean up floodwater in the house without dumping it into the sinks or toilet.

- Avoid digging around the septic tank and drain field while the soil is water logged. Don’t drive heavy vehicles or equipment over the drain field. By using heavy equipment or working under water-logged conditions, you can compact the soil in your drain field, and water won’t be able to drain properly.

- Don’t open or pump out the septic tank if the soil is still saturated. Silt and mud can get into the tank if it is opened, and can end up in the drain field, reducing its drainage capability. Pumping under these conditions can also cause a tank to pop out of the ground.

- If you suspect your system has been damage, have the tank inspected and serviced by a professional. How can you tell if your system is damaged? Signs include: settling, wastewater backs up into household drains, the soil in the drain field remains soggy and never fully drains, and/or a foul odor persists around the tank and drain field.

- Keep rainwater drainage systems away from the septic drain field. As a preventive measure, make sure that water from roof gutters doesn’t drain into your septic drain field – this adds an additional source of water that the drain field has to manage.

More information on septic system maintenance after flooding can be found on the EPA website publication https://www.epa.gov/ground-water-and-drinking-water/septic-systems-what-do-after-flood

By taking special care with your septic system after flooding, you can contribute to the health of your household, community and environment.

by Andrea Albertin | Mar 18, 2018

An estimated 2.5 million Floridians (approximately 12% of the population) rely on private wells for home consumption, which includes water for drinking, cooking, bathing, washing, toilet flushing and other needs. While public water systems are regulated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to ensure safe drinking water, private wells are not regulated. Private well users are responsible for ensuring the safety of their own drinking water.

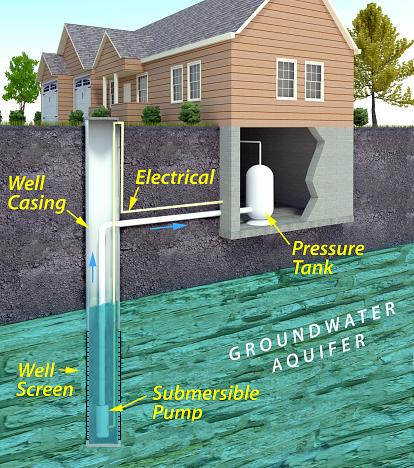

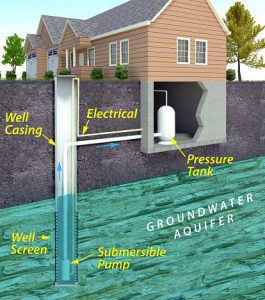

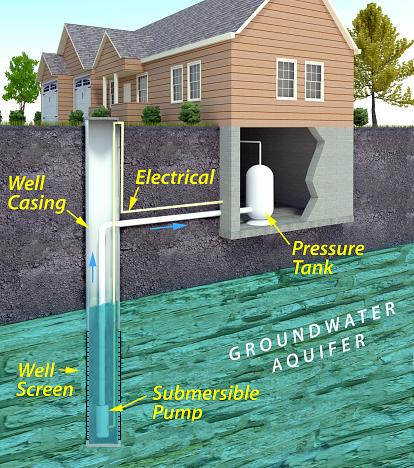

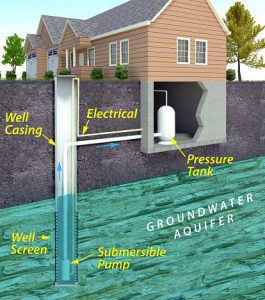

Schematic of a private well typical of many areas in the U.S. Source: usepa.gov

The In Florida, pressure tanks are located above ground since basements are not common. The well casing ensures that water is drawn from the desired ground water source – the bottom of the well where the well screen is placed. The screen keeps sediment from getting into the well, and is usually made of perforated or slotted pipe. The well cap on the surface prevents debris and animals from getting into the well. Submersible pumps (shown here) are set inside the well casing and used for deep wells. Jet pumps are used on the surface and can be used for both shallow and deep wells.

How can well users make sure that their water is safe to drink?

It’s important to have well water tested at a certified laboratory at least once a year for contaminants that can cause health problems. According to the Florida Department of Health (FDOH), the most common contaminants in well water in Florida are bacteria and nitrates.

Bacteria: Labs generally test for Total coliform bacteria and fecal coliforms (or E. coli specifically) when a sample is submitted for bacteriological testing. This generally costs about $25 to $30, but can vary depending on where you have your sample analyzed.

Coliform bacteria are a large group of different kinds of bacteria and most species are harmless and will not make you sick. But, a positive test for total coliforms indicate that bacteria are getting into your well water. Coliforms are used as indicator organisms – if coliform bacteria are in your well, other pathogens (bacteria, viruses or protozoans) that cause diseases may also be getting into your well water. It is easier and cheaper to test for total coliforms than a suite of bacteria and other organisms that can cause health problems.

Fecal coliform bacteria are a subgroup of coliform bacteria found in human and other warm-blooded animal feces. E. coli are one species of fecal coliform bacteria. A positive test for fecal coliform bacteria or E. coli indicate that water has been contaminated by human or animal waste.

If your water sample tests positive for only total coliform bacteria or both total coliform and fecal coliform (or E. coli), the Department of Health recommends that your well be disinfected. This is generally done through shock chlorination. You can either hire a well operator in your area to disinfect your well or you can do it yourself. Information for how to shock chlorinate your own well can be found

Nitrates: The U.S. EPA set the Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL) for nitrate in drinking water at 10 miligrams per liter of water (mg/L). Values above this are a concern for infants who are less than 6 months old because high nitrate levels can cause a type of “blue baby syndrome” (methemoglobinemia), where nitrate interferes with the capacity of hemoglobin in the blood to carry oxygen. It is particularly important to test for nitrate if you have a young infant in the home that will be drinking well water or when well water will be used to make formula to feed the infant.

If test results come back above 10 mg/L, never boil nitrate contaminated water as a form of treatment. This will not remove nitrates. Use water from a tested source (bottled water or water from a public supply source) until the problem is addressed.

Nitrates in well water come from fertilizers applied on land surfaces, animal waste and/or human sewage, such as from a septic tank. Have your well inspected by a professional to identify why elevated nitrate levels are is getting into your well water. You can also consider installing a water treatment system, such as reverse osmosis or distillation units to treat the contaminated water. Before having a system installed, make sure you contact your local health department or a water treatment contractor for more information.

Where can you have your well water tested?

Most county health departments accept samples for water testing. You can also submit samples to a certified commercial lab near you. Contact your county health department for information about what to have your water tested for and how to take and submit the sample.

Contact information for county health departments can be found on this site: http://www.floridahealth.gov/programs-and-services/county-health-departments/find-a-county-health-department/index.html

You can search for laboratories near you certified by FDOH here: https://fldeploc.dep.state.fl.us/aams/loc_search.asp This includes county health department labs as well as commercial labs, university labs and others.

You should also have your well water tested at any time when:

- The color, taste or odor of your well water changes or if you suspect that someone became sick after drinking your well water.

- A new well is drilled or if you have had maintenance done on your existing well

- A flood occurred and your well was affected

Remember: Bacteria and nitrate are by no means the only parameters that well water is tested for. Call your local health department to discuss your water and what they recommend you should get the water tested for. The Florida Department of Health (FDOH) also maintains an excellent website with many resources for private well users: http://www.floridahealth.gov/environmental-health/private-well-testing/index.html . This site includes information on potential contaminants and how to maintain your well to ensure the quality of your well water.

by Rick O'Connor | Jul 29, 2017

ARTICLE BY DR. MATT DEITCH; water quality specialist – University of Florida Milton

Summer is a great time for weather-watching in the Florida panhandle. Powerful thunderstorms appear out of nowhere, and can pour inches of rain in an area in a single afternoon. Our bridges, bluffs, and coastline allow us to watch them develop from a distance. Yet as they come closer, it is important to recognize the potential danger they pose—lightning from these storms can strike anywhere nearby, and can cause fatality for a person who is struck. Nine people were killed by lightning strike in Florida in 2016 alone, more than in any other state. Because of the risk posed by lightning, my family and I enjoy these storms up-close from indoors.

Carpenter’s Creek in Pensacola

Photo: Dr. Matt Deitch

A fraction of the rain that falls during these storms is delivered to our bays, bayous, and estuaries through a drainage network of creeks and rivers. This streamflow serves several important ecological functions, including preventing vegetation encroachment and maintaining habitat features for fish and amphibians through scouring the streambed. High flows also deposit fine sediment on the floodplain, helping to replenish nutrients to floodplain soil. On average, only about one-third of the water that falls as rain (on average, more than 60 inches per year!) turns into streamflow. The rest may either infiltrate soil and percolate into groundwater; or be consumed and transpired by plants; or evaporate off vegetation, from the soil, or the ground surface before reaching the soil. Evaporation and transpiration play an especially large role in the water cycle during summer: on average, most of the rain that falls in the Panhandle occurs during summer, but most stream discharge occurs during winter.

The water that flows in streams carries with it many substances that accumulate in the landscape. These substances—which include pollutants we commonly think of, such as excessive nutrients comprised of nitrogen and phosphorus, as well as silt, oil, grease, bacteria, and trash—are especially abundant when streamflow is high, typically during and following storm events. Oil, grease, bacteria, and trash are especially common in urban areas. The United States EPA and Florida Department of Environmental Protection have listed parts of the Choctawhatchee, St. Andrew, Perdido, and Pensacola Bays as impaired for nutrients and coliform bacteria. Pollution issues are not exclusive to the Panhandle: some states (such as Maryland and California) have even developed regulatory guidelines in streams (TMDLs) for trash!

Many local and grassroots organizations are taking the lead on efforts to reduce pollution. Some municipalities have recently publicized efforts to enforce laws on picking up pet waste, which is considered a potential source of coliform bacteria in some places. Some conservation groups in the panhandle organize stream debris pick-up days from local streams, and others organize volunteer citizens to monitor water quality in streams and the bays where they discharge. Together, these efforts can help to keep track of pollution levels, demonstrate whether restoration efforts have improved water quality, and maintain healthy beaches and waterways we rely on and value in the Florida Panhandle.

Santa Rosa Sound

Photo: Dr. Matt Deitch

by Andrea Albertin | Apr 29, 2017

One third of homes in Florida rely on septic systems, or onsite sewage treatment and disposal systems (OSTDS), to treat and dispose of household wastewater, which includes wastewater from bathrooms, kitchen sinks and laundry machines. When properly maintained, septic systems can last 25-30 years, and maintenance costs are relatively low.

A conventional residential septic tank and drain field under construction.

Photo: Andrea Albertin

A general rule of thumb is that with proper care, systems need to be pumped every 3-5 years at a cost of about $300 to $400. Time between pumping does vary though, depending on the size of your household, the size of your septic tank and how much wastewater you produce. If systems aren’t maintained they can fail, and repairs or replacing a tank can cost anywhere between $3000 to $10,000. It definitely pays off to maintain your septic system!

The most common type of OSTDS is a conventional septic system, which is made up of a septic tank (a watertight container buried in the ground) and a drain field, or leach field. The septic tank’s job is to separate out solids (which settle on the bottom as sludge), from oils and grease, which float to the top and form a scum layer. The liquid wastewater, which is in the middle layer of the tank, flows out through pipes into the drainfield, where it percolates down through the ground.

Although bacteria continually work on breaking down the organic matter in your septic tank, sludge and scum will build up, which is why a system needs to be cleaned out periodically. If not, solids will flow into the drainfield clogging the pipes and sewage can back up into your house. Overloading the system with water also reduces its ability to work properly by not leaving enough time for material to separate out in the tank, and by flooding the system. Sewage can flow to the surface of your lawn and/or back up into your house.

Failed septic systems not only result in soggy lawns and horrible smells, but they contaminate groundwater, private and public supply wells, creeks, rivers and many of our estuaries and coastal areas with excess nutrients, like nitrogen, and harmful pathogens, like E. coli.

It is important to note that even when traditional septic systems are maintained, they are still a source of nitrogen to groundwater; nitrate is not fully removed from the wastewater effluent.

How can you properly care for your septic system?

Here are a some basic tips to keep your system working properly so that you can reduce maintenance costs by avoiding system failure, and so that you can reduce your household’s impact on water pollution in your area.

- Don’t flush trash down the toilet. Only flush regular toilet paper. Toilet paper treated with lotion forms a layer of scum. Wet wipes are not flushable, although many brands are labelled as such. They wreak havoc on septic systems! Avoid flushing cigarette butts, paper towels and facial tissues, which can take longer to break down than toilet paper.

- Think at the sink. Avoid pouring oil and fat down the kitchen drain. Avoid excessive use of harsh cleaning products and detergents, which can affect the microbes in your septic tank (regular weekly or so cleaning is fine). Prescription drugs and antibiotics should never be flushed down the toilet.

- Limit your use of the garbage disposal. Disposals add organic matter to your septic system, which results in the need for more frequent pumping. Composting is a great way to dispose of your fruit and vegetable scraps instead.

- Take care at the surface of yourtank and drainfield. To work well, a septic system should be surrounded by non-compacted soil. Don’t drive vehicles or heavy equipment over the system. Avoid planting trees or shrubs with deep roots that could disrupt the system or plug pipes. It is a good idea to grow grass over the drainfield to stabilize soil and absorb liquid and nutrients.

- Conserve water. You can reduce the amount of water pumped into your septic tank by reducing the amount you and your family use. Water conservation practices include repairing leaky faucets, toilets and pipes, installing low cost, low-flow showerheads and faucet aerators, and only running the washing machine and dishwasher when full. In the US, most of the household water used is to flush toilets (about 27%). Placing filled water bottles in the toilet tank is an inexpensive way to reduce the amount of water used per flush.

- Have your septic system pumped by a certified professional. The general rule of thumb is every 3-5 years, but it will depend on household size, the size of your septic tank and how much wastewater you produce.

By following these guidelines, you can contribute to the health of your family, community and environment, as well as avoid costly repairs and septic system replacements.

You can find excellent information on septic systems a the US EPA website: https://www.epa.gov/septic. The Florida Department of Health website provides permiting information for Florida and a list of certified maintenance entities by county: http://www.floridahealth.gov/Environmental-Health/onsite-sewage/index.html.

The Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP) identified septic systems as the major source of nitrate in Wakulla Springs, located in Wakulla County. Excess nitrate is thought to promote algal growth, leading to the degradation of the biological community in the spring.

Photo: Andrea Albertin