by Rick O'Connor | May 16, 2025

As far as familiarity goes – everyone knows about worms. As far as seeing them – these are rarely, if ever seen by visitors to the northern Gulf. Most know worms as creatures that live beneath the sand – out of sight and doing what worms do. We imagine – scanning the landscape of the Gulf – millions of worms buried beneath the sediment. For some this may be quite unnerving. Worms are sometimes “gross” and associated with an unhealthy situation. You might say to your kids “don’t dig in the sand – you might get worms”. Or even “don’t drink the water – you might get worms”. But the reality of it all is that there are many kinds of worms in the northern Gulf, and many are very beneficial to the system. We will look at a few.

The common earthworm.

Photo: University of Wisconsin Madison

Flatworms are the most primitive of the group. As the name implies, they are flat. There is a head end, often with small eyespots that can detect light, but the mouth is in the middle of the body and, like the jellyfish, is the only opening for eating and going to the restroom. There are numerous species of flatworms that crawl over the ocean floor feeding on decayed detritus, many are brightly colored to advertise the fact they are poisonous – or pretending to be poisonous. And then there are species that actually swim – undulating through the water in a pattern similar to what we do with our hand when we stick it out the window driving at high speed.

But there are parasitic flatworms as well. Worms such as the tapeworm and the flukes are more well known than the free-swimming flatworms just described. These are the worms people become concerned about when they hear “there are worms out there”. And yes – they do exist in the northern Gulf. But what some people may not realize is that these internal parasites are adapted for the internal environment of their selected host and cannot survive in other creatures. There are human tapeworms and flukes, but they are not found in the sands of the Gulf.

The human liver fluke. One of the trematode flatworms that are parasitic.

Photo: University of Pennsylvania

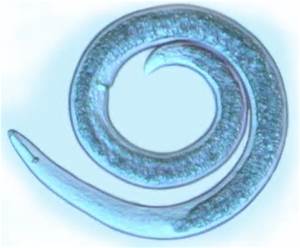

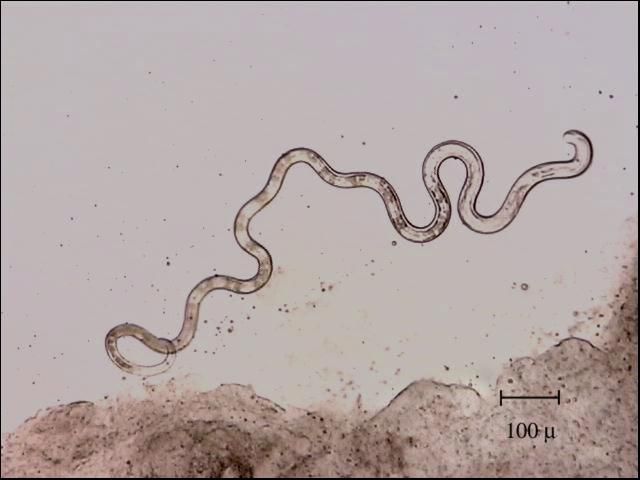

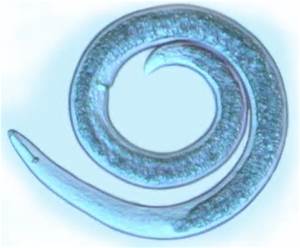

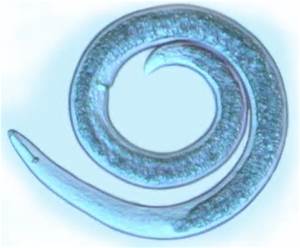

As the name implies, roundworms are round – but they differ from earthworms in that their bodies are smooth and not segmented as earthworms are. One group of roundworms is well known in the agriculture and horticulture world – nematodes. Some nematodes are also known for being human parasites – again, creating some concern. These include the hookworm and pinworm. Roundworms can be found in the sediments by the thousands – sometimes in the millions. The abundance of some species are used as an indicator of the health of the system – the more of these particular type of roundworms, the more unhealthy the system – again, a cause of concern for some when they see any worm in the sand.

The round body of a microscopic nematode.

Photo: University of Nebraska at Lincoln

We will end with the segmented worms – the annelids. This is the group in which the familiar earthworm belongs. Though earthworms do not exist in the northern Gulf, their cousins – the polychaetae worms – are very common. Polychaetas are much larger, easier to see, and differ from earthworms in that they have extended legs from each segment called parapodia. Some polychaetas produce tubes in which they live. They will extend their antenna out to collect food. Many of these tubeworms have their tubes beneath the sand and we only see them (rarely) when their tentacles are extended – or when they extend a gelatinous mass from their tubes to collect food. But there is a type of tubeworm – the sepurlid worms – that produce small skinny calcium carbonate tubes on the sides of rocks on rock jetties, pier pilings, and even marine debris left in the water. This is also the group that the leech belongs to. Though leeches are more associated with freshwater, there are marine leeches. These are rarely encountered and do not attach to humans as their freshwater cousins do.

Diopatra are segmented worms similar to earthworms who build tubes to live in. These tubes are often found washed up on the beach.

Though we may be “creeped-out” about the presence of worms in the northern Gulf of Mexico, they are none threatening to us and are an important member of the marine community cleaning decaying creatures and waste material from the environment. We know they are there, and glad they are there.

by Rick O'Connor | Aug 23, 2024

Roundworms differ from flatworms in that… well… they are round. You might recall from Part 1 of this series that flatworms were flat which helps with exchange of materials inside and out of the body. Flatworms were acoelomates – they lack an interior body cavity and thus lack internal organs. So, gas exchange (etc.) must occur through the skin. And a flat body increases the surface area in order to do this more efficiently.

A common nematode.

Photo: University of Florida

But roundworms are round, which reduces this surface area and reduces the efficiency of material exchange through the skin. Though gas exchange through the skin does happen, it is not as efficient. So, there is the need for internal organs and that means there is a need for an internal body cavity to hold these organs. But with the roundworms there is only a partial cavity, not a complete one, and the term pseudocoelomate is used for them. Though the round body has adaptations to deal with gas exchange, it is a better shape for burrowing in the soil and sediment.

There are about 25,000 described species of roundworms, though some estimate there may be at least 500,000. They are placed in the Phylum Nematoda and are often called nematodes. Nematodes live within the interstitial spaces of soil, sediment, and benthic plant communities. They have been found in the polar regions, the tropics, the bottom of the sea, and in deserts – they are everywhere. They are usually in high numbers. One square meter of mud from a beach in Holland had over 4,000,000 nematodes. Scientists have estimated that an acre of farmland may have at least 1 billion of them. A decomposing apple on the ground in an orchard had about 90,000 nematodes. So, they are found everywhere and usually in great abundance. There are parasitic forms as well and they attack almost all groups of plants and animals. Food crops, livestock, and humans have made this group of nematodes a concern in our society.

Like many pseudocoelomates, nematodes have an anterior end with a mouth, but no distinct head – rather two tapered ends. Most of the free-living nematodes are less than 3mm (0.1in), but some soil nematodes can reach lengths of 7mm (0.3in) and there are marine nematodes that can reach 5cm (2in.) – it is a group of small worms.

Roundworms usually need water in order to move, even the soil species. They typically wriggle and undulate, similar to a snake, when moving and under a microscope they wriggle quite fast. In aquatic habitats they may swim for a short distance, and a few terrestrial species can crawl through dry sand.

Marine Nematode – Dr. Roy P. E. Yanong, UF/IFAS Tropical Aquaculture Lab

Many free-living nematodes are carnivorous and feed on tiny animals and other nematodes. Some feed on microscopic algae and fungi. Some terrestrial species pierce the roots of plants and digest the material within. Many marine species will feed on detritus lying on the seafloor. The carnivorous species may possess small teeth, and many have a stylet they can use to pierce prey or the plant root to access food. The mouth leads to a long digestive tract and eventually an anus – nematodes have a complete digestive tract.

The brain is basically a nerve ring near the head that leads to numerous nerve chords that run the length of the body. Sensory cells are most associated with the sense of touch and smell.

Having separate sexes is the rule for nematodes, but not for all. Males are usually much smaller and usually have a hooked posterior end which they use to hold the female during mating. 50-100 eggs are usually produced and laid within the environment.

Farmers and horticulturists are familiar with these free-living nematodes, but it is the parasitic ones that are most known to the general public. There are many different forms of parasitism within nematodes. Dr. L.H. Hyman categorized them as follows:

- Ectoparasites that feed on the external cells of plants – using their stylet to pierce the plant tissue and remove nutrients.

- Endoparasites of plants. Juveniles of some nematodes enter plants and feed on tissue. This can cause tissue death and gall-like structures.

- Some free-living nematodes, while juveniles, will enter the bodies of invertebrates and feed on the tissue when the invertebrate dies.

- Endoparasites within invertebrates as juveniles, but the adult stage is free-living.

- Some are plant parasites as juveniles and animal parasites as adults. The females live within the bodies of plant eating insects, where they give birth to their young. When the insects pierce the plant tissue, the juveniles enter the plant and begin feeding on it. When they mature into adults, they re-enter the insects and the cycle begins again.

- Those that live within animals. The eggs, or newly hatched young, may be free-living for a short period, where they find new animal hosts, but the majority of the life cycle occurs within the animal. Many known to us infect dogs, cats, pigs, cattle, horses, chickens, fish, and humans.

Heartworms, pinworms, and hook worms are names you may have heard. For dog nematodes, the eggs are released into the environment by the dog’s feces. Another dog eats this feces and becomes infected.

The nematode known as Ascaris lumbricoides is the most common parasitic worm in humans. It has been estimated that almost 1 billion people are infected with it. Female Ascaris release developing eggs into the environment via human feces. Other humans become infected after swallowing food or water containing the eggs. Once inside the human, the eggs hatch and penetrate the tissue moving into the heart and eventually the lungs. From here they crawl up the trachea inducing a coughing response which is followed by a swallowing response that moves the developing juvenile worm into the esophagus and eventually back to the intestines where the cycle begins again. Infections of this worm are more common where sanitation systems are not adequate and/or human feces are used as a fertilizer.

Hookworms are another human parasite that feed on blood and can cause serious infections in humans due to blood and tissue loss. Fertilized eggs of this worm are laid in the environment and re-enter new human host as developing juveniles by penetrating their skin. Once in the new host the developing worms are carried to the lungs via the circulatory system and work their way into the pharynx, are swallowed, and eventually end up in the intestine. Not all hookworm juveniles penetrate through the skin but rather enter the body when the person unknowingly consumes human feces. This can happen from not washing your hands or food (if human waste is used as fertilizer). Pinworms and whipworms are other nematodes that have similar life cycles. In Asia there are some nematodes that are passed to humans by biting insects.

The roundworm known as the nematode is a common issue for farmers, horticulturists, and as a parasite in some parts of the world. Their lifestyles, while being a potential problem for us, have been very successful for them. In the next edition in this series, we will learn more about the most advanced worms on our planet – the segmented worms. We will begin with the polychaetes.

References

Barnes, R.D. (1980). Invertebrate Zoology. Saunders Publishing. Philadelphia PA. pp. 1089.

Ascaris lumbricoides. 2024. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ascaris_lumbricoides.

by Rick O'Connor | Aug 10, 2024

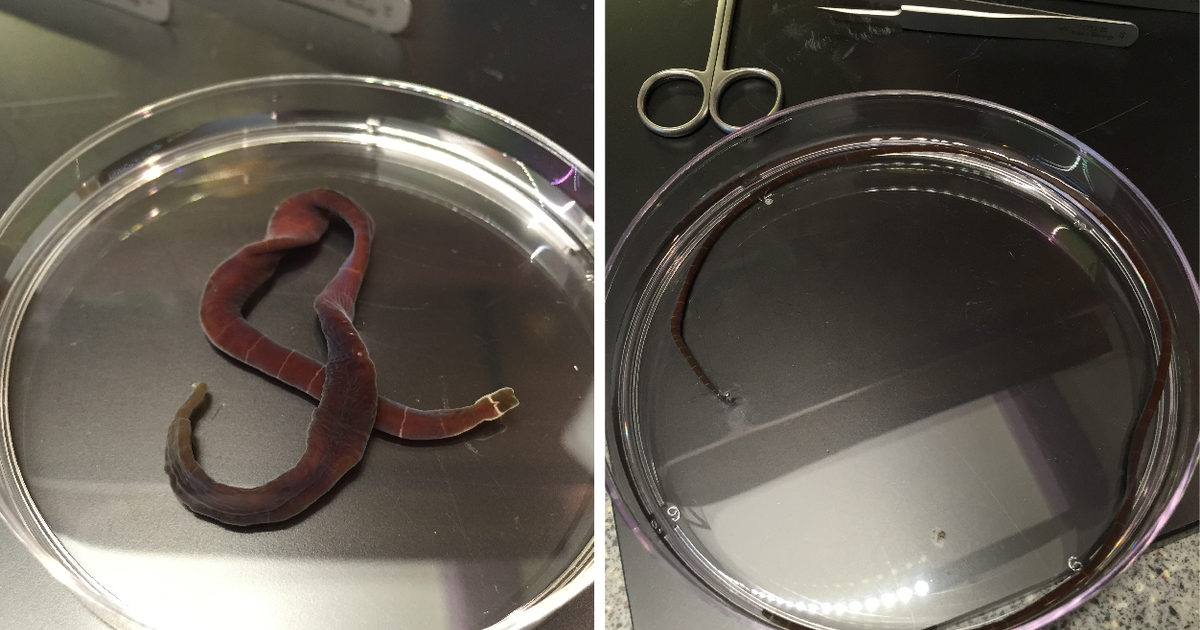

I bet that for most of you, this is not only a worm you have never seen – it is a worm you have never heard of before. I learned about them first in college, which was almost 50 years ago, and have never seen one. But, other than the earthworm, the world of worms is basically hidden from us.

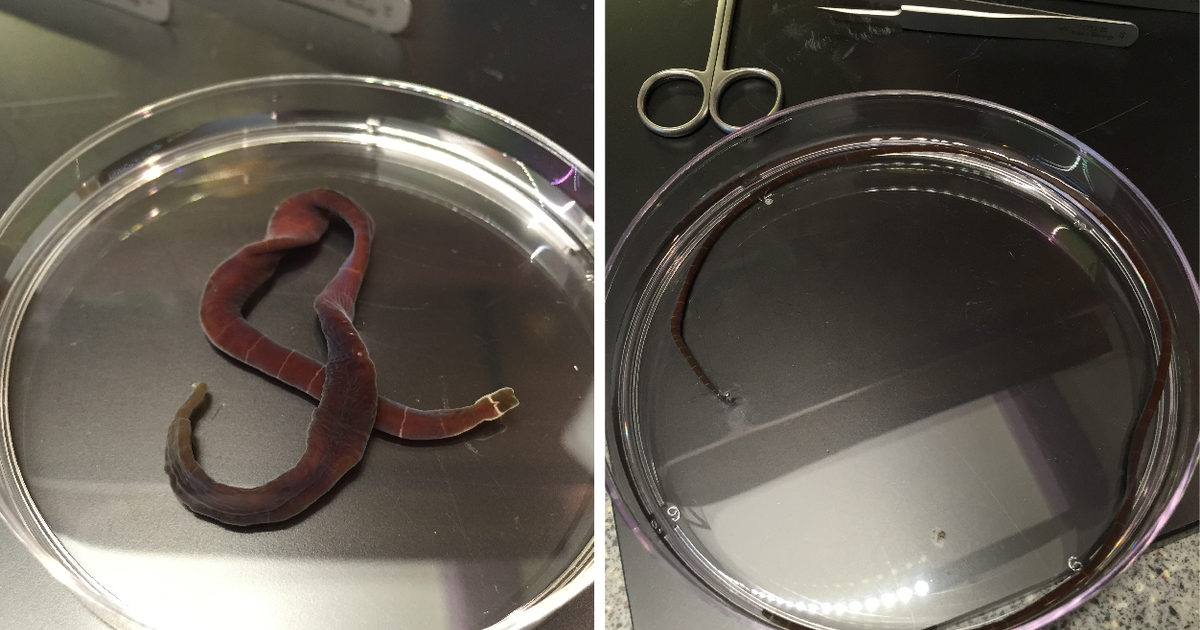

A nemertean worm.

Photo: Okinawa Institute of Science

Nemerteans are a group of about 1300 species in the Phylum Nemertea and are often called ribbon or proboscis worms. They do possess a proboscis used to capture prey. Most are marine and live on the bottom both near the beach and a great depth. They are more temperate than tropical and do have a few parasitic forms.

Adult Nemertea Worms – Terra C. Hiebert, PhD, Oregon University

In appearance they resemble flatworms but are larger and more elongated. Most are less than 20cm (8in) but some species along the Atlantic coast can reach 2m (7ft). The head end can be lobed or even spatula looking. Some species are pale in color and others quite colorful. Most nemerteans move over the substrate on a trail of slime produced by their skin. Some species can swim.

As mentioned, the proboscis is used to capture prey. It is a tube-like structure held in a sac near the head. When prey is detected, they can launch the proboscis out and over the victim. Sticky secretions help hold on to the prey while they ingest. Many species are armed with a stylet, dart, that is attached to the proboscis and is driven into the prey like a spear. From there toxins, secreted from the base of the proboscis are injected into the prey.

For many species the proboscis is connected to the digestive tract via a tube, there is no true mouth, but they do possess an anus. They are all carnivorous and feed on a variety of small living and dead invertebrates. Their menu includes annelid worms, mollusk, and crustaceans.

Nemerteans do possess a brain and most find their prey using chemoreception, though some species must literally bump into their prey to find it. They have multiple eyes that can detect light, and, like the true flatworms, they are negatively phototaxic. They are nocturnal by habitat and is probably why most of us have never seen one.

Many nemerteans, particularly the larger ones, have a habit of fragmenting when irritated, creating new worms. Most species have separate sexes and fertilization of the gametes is external (fertilization occurs in the environment).

Nemerteans are an interesting group of semi-large, sometimes toxic, hunters who prowl through the marine waters at night hunting prey. Seen by few, maybe one evening, while exploring or floundering, you may see one.

In Part 3 we will begin to explore a group of worms that are more round than flat. The Gastrotrichs.

Reference

Barnes, R.D. (1980). Invertebrate Zoology. Saunders Publishing. Philadelphia PA. pp. 1089.

by Rick O'Connor | Jul 26, 2024

People enjoy animals. Zoos and wildlife parks are popular tourist destinations and animal programs are popular on television. It is usually the larger predator animals that get our attention. Sharks, panthers, and bears are popular. People like turtles, raptors, and snakes. Other animals are popular as well like antelope, elephants, and deer.

The green sea turtle.

Photo: Mike Sandler

At public aquariums you see exhibits with whales, sharks, and sea turtles. You also see tanks with reef fish, crabs, and octopus drawing crowds. But one group of animals that has never really drawn attention – either at public parks or wildlife television shows – are worms.

Worms are a world of the creepy and gross. To us, their presence suggests dirtiness or environmental problems. But worms are abundant in our environment and play an important role in ecology. In this series we will meet some of them and learn more about their lives. We begin with the flatworms.

As the name suggests, flatworms have flat bodies. In many species their heads can be identified by the presence of eyespots. Eyespots differ from eyes in that they detect light, but do not provide an actual image. Biologists describe animals as being either positively or negatively phototaxic. Most flatworms are negatively phototaxic, they do not like light. To them, light indicates daytime. A time when the predators can see and attack them. So, when they detect light, they move under rocks, mud, whatever to avoid being detected.

Most flatworms are less than 10mm (0.4 in) in length, though some are 60 cm (24 inches). They possess a mouth on their belly side (ventral) and often it is in the middle of the animal, not at the head end. This mouth leads to a simple stomach, but they lack an anus so solid waste must exit the worm through the mouth – what is called an incomplete digestive system.

This colorful worm is a marine turbellarian.

Photo: University of Alberta

One class of flatworms are the free-swimming turbellarians. Most are carnivorous, feeding on small invertebrates and dead carcasses. Some feed on sessile creatures like oysters and barnacles. And some feed on microscopic plants like diatoms. The carnivorous species wrap their prey with their bodies secreting slime over them. They engulf their prey whole. There are two classes of flatworms that are parasitic: the trematodes (flukes), and the cestodes (tapeworms).

Flatworms lack an internal body cavity (coelom) and thus lack internal organs. Not having lungs and kidneys they must take in need gases, and other materials, and well as expel nitrogenous waste, through their skin. Being flat increases their surface area and the efficiency of doing this. This is why they are flat.

Reproduction in flatworms occurs in different ways. Some will reproduce asexually by simple fission – they split apart producing two worms. Many species reproduce sexually using sperm and egg.

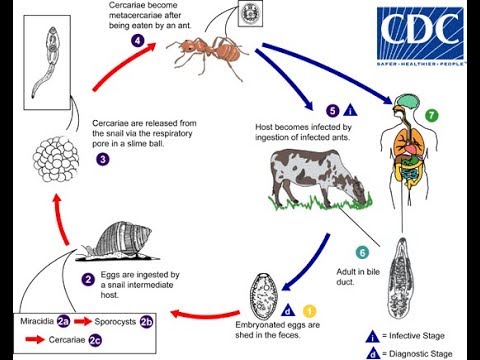

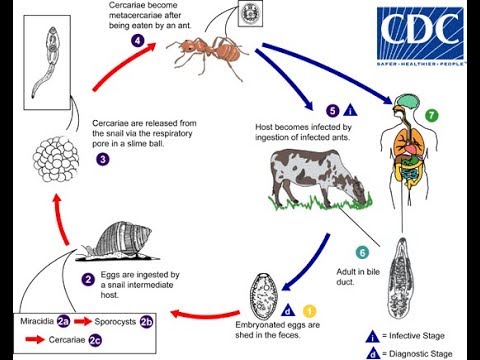

Another class of flatworms are the parasitic trematodes; commonly called flukes. They resemble turbellarians in body shape and design, though the mouth is usually at the head end. Most are only a few centimeters long, but one can reach the length of 7 meters (24 feet)! Their bodies are covered with a skin-like material that protects them from the digestive enzymes of their hosts.

The human liver fluke. One of the trematode flatworms that are parasitic.

Photo: University of Pennsylvania

As with turbellarians, flukes are hermaphroditic but use internal fertilization with other worms to produce young, though self-fertilization can – and does – happen. Their life cycles can include one or several hosts. The primary host, the one the adults reside in, are usually vertebrates, most often fish. The intermediate hosts, the ones the juveniles reside in, are often snails but can be other species.

Life cycle of a trematode. Image: Center for Disease Control.

The life cycle is complex, but a general one would include the fertilized eggs being encased in a shell and released into the environment via the feces of the primary host. A ciliated larval stage hatches from this egg and is either consumed by the intermediate host or penetrates the skin of it. Once inside the second larval stage begins. This eventually becomes a third and fourth larval stage. At the fourth larval stage the young worm possesses a mouth and digestive tract. At this stage it leaves the intermediate host as a free-swimming larva seeking a second intermediate host. Here it goes through more larval stages and eventually becomes encased within a cyst (a hard shell). The encysted larva stage enters the primary host (a vertebrate) after that primary host consumes the second intermediate host. Here it develops into the adult trematode.

A third class of flatworms are the parasitic tapeworms – Class Cestoda. Tapeworms differ from other flatworms in that they have a round head – called a scolex – attached to a flat body, and they lack a digestive tract. The flat part of the body is made up of small square segments called proglottids. They continually add proglottids and can become quite long – some have measured over 40 feet! The scolex has four suckers and a ring of small hooks with which they can attach to the inner lining of the digestive tract with.

The famous tapeworm.

Photo: University of Omaha.

The reproductive organs occur within the proglottids. Cross fertilization between these hermaphroditic worms is the rule but self-fertilization does happen. The fertilized eggs are released when the proglottid ruptures and exit the host via the feces.

Tapeworms do require intermediate hosts. The extruded egg hatches into a ciliated larva which is consumed by the intermediate host before that host is consumed by the primary host – typically a vertebrate.

As we can see the lives of these flatworms are (1) secretive, and (2) not pleasant to think about. But they do play a role in our marine and estuarine ecosystem and are very successful at what they do. They should be appreciated for their success.

In our next article on the World of Worms we will look at the nemerteans.

Reference

Barnes, R.D. (1980). Invertebrate Zoology. Saunders Publishing. Philadelphia PA. pp. 1089.

by Scott Jackson | May 26, 2022

Nutrients found in food waste are too valuable to just toss away. Small scale composting and vermicomposting provide opportunity to recycle food waste even in limited spaces. UF/IFAS Photo by Camila Guillen.

During the summer season, my house is filled with family and friends visiting on vacation or just hanging out on the weekends. The kitchen is a popular place while waiting on the next outdoor adventure. I enjoy working together to cook meals, bbq, or just make a few snacks. Despite the increased numbers of visitors during this time, some food is leftover and ultimately tossed away as waste. Food waste occurs every day in our homes, restaurants, and grocery stores and not just this time of year.

The United States Food and Drug Administration estimates that 30 to 40 percent of our food supply is wasted each year. The United States Department of Agriculture cites food waste as the largest type of solid waste at our landfills. This is a complex problem representing many issues that require our attention to be corrected. Moving food to those in need is the largest challenge being addressed by multiple agencies, companies, and local community action groups. Learn more about the Food Waste Alliance at https://foodwastealliance.org

According to the program website, the Food Waste Alliance has three major goals to help address food waste:

Goal #1 REDUCE THE AMOUNT OF FOOD WASTE GENERATED. An estimated 25-40% of food grown, processed, and transported in the U.S. will never be consumed.

Goal #2 DONATE MORE SAFE, NUTRITIOUS FOOD TO PEOPLE IN NEED. Some generated food waste is safe to eat and can be donated to food banks and anti-hunger organizations, providing nutrition to those in need.

Goal #3 RECYCLE UNAVOIDABLE FOOD WASTE, DIVERTING IT FROM LANDFILLS. For food waste, a landfill is the end of the line; but when composted, it can be recycled into soil or energy.

All these priorities are equally important and necessary to completely address our country’s food waste issues. However, goal three is where I would like to give some tips and insight. Composting food waste holds the promise of supplying recycled nutrients that can be used to grow new crops of food or for enhancing growth of ornamental plants. Composting occurs at different scales ranging from a few pounds to tons. All types of composting whether big or small are meaningful in addressing food waste issues and providing value to homeowners and farmers. A specialized type of composting known as vermicomposting uses red wiggler worms to accelerate the breakdown of vegetable and fruit waste into valuable soil amendments and liquid fertilizer. These products can be safely used in home gardens and landscapes, and on house plants.

Composting meat or animal waste is not recommended for home composting operations as it can potentially introduce sources of food borne illness into the fertilizer and the plants where it is used. Vegetable and Fruit wastes are perfect for composting and do not have these problems.

Composting worms help turn food waste into valuable fertilizer. UF/IFAS Photo by Tyler Jones

Detailed articles on how vermicomposting works are provided by Tia Silvasy, UF/IFAS Extension Orange County at https://blogs.ifas.ufl.edu/orangeco/2020/12/10/vermicomposting-using-worms-for-composting and https://sfyl.ifas.ufl.edu/media/sfylifasufledu/orange/hort-res/docs/pdf/021-Vermicomposting—Cheap-and-Easy-Worm-Bin.pdf Supplies are readily available and relatively inexpensive. Please see the above links for details.

A small vermicomposting system would include:

• Red Wiggler worms (local vendors or internet)

• Two Plastic Storage Bins (approximately 30” L x 20” W x 17” H) with pieces of brick or stone

• Shredded Paper (newspaper or other suitable material)

• Vegetable and Fruit Scraps

Red Wiggler worms specialize in breaking down food scraps unlike earthworms which process organic matter in soil. Getting the correct worms for vermicomposting is an important step. Red Wigglers can consume as much as their weight in one day! Beginning with a small scale of 1 to 2 pounds of worms is a great way to start. Sources and suppliers can be readily located on the internet.

Worm “homes” can be constructed from two plastic storage bins with air holes drilled on the top. Additional holes put in the bottom of the inner bin to drain liquid nutrients. Pieces of stone or brick can be used to raise the inner bin slightly. Picture provided by UF/IFAS Extension Leon County, Molly Jameson

Once the worms and shredded paper media have been introduced into the bins, you are ready to process kitchen scraps and other plant-based leftovers. Food waste can be placed in the worm bins by moving along the bin in sections. Simply rotate the area where the next group of scraps are placed. See example diagram. For additional information or questions please contact our office at 850-784-6105.

Placing food scraps in a sequential order allows worms to find their new food easily. Contributed diagram by L. Scott Jackson

Portions of this article originally published in the Panama City News Herald

UF/IFAS is An Equal Opportunity Institution.