by Evan Anderson | Jun 5, 2025

The Eastern Lubber Grasshopper

From spring to early summer every year, a certain grasshopper can be seen in the Florida panhandle: the eastern lubber, also known as the Georgia thumper. Sometimes emerging in huge numbers, this can be distressing to residents who suddenly find themselves amidst what might appear to be a plague of biblical proportions. Females lay eggs in the soil, and seem to prefer woodland areas with soil that is neither too wet or too dry. With each female laying one or more ‘pods’ of eggs, and each pod containing up to 80 eggs, this can lead to a lot of grasshoppers!

Nymphs are the young and immature form of the grasshopper, and appear different than the adults. Newly hatched lubbers are black with a yellow, orange, or red stripe running down their backs. They range from about ½ inch to 1 ¾ inch long while still in the nymphal stage, and tend to stay together in groups. Adults are seen most often starting in July, growing to a size of up to 3 ½ inches in length. Adults may remain black, but are often seen in lighter colors, from yellow to orange.

An adult eastern lubber grasshopper.

Eastern lubbers feed on a wide variety of plants. While adults prefer low, wet areas, they will sometimes damage crops or ornamental plants. They eat less than one might expect, given their size, but groups can still defoliate plants if left unchecked. Thankfully, they cannot fly, and therefore do not range over a wide area individually.

If these grasshoppers become a problem in landscapes or gardens, control methods are best undertaken early, while the insects are young. If populations are not great, they can be hand picked and removed. If treatment with insecticide is desired, there are several products available that kill lubbers. For individuals desiring a more ‘natural’ insecticide, products with the active ingredient spinosad are relatively safe to use, if slow acting. Spinosad should be applied in the early morning, late evening, or at night, to avoid affecting foraging pollinators such as bees.

Other insecticides will also work, including those with the active ingredients carbaryl, bifenthrin, cyhalothrin, permethrin, or esfenvalerate. Note that the active ingredient may not be the same as the brand name, and may only be listed in smaller print in the ‘ingredients’ portion of the product’s label. Avoid applying insecticides too close to water bodies, as they may harm fish.

For more information, see the EDIS publication on eastern lubbers at https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/IN132.

Evan Anderson

Walton County Horticulture Agent

by Mark Tancig | May 28, 2025

Extension Agents get used to hearing that the local Extension Office is the community’s best kept secret. As much as we try to let folks know we’re here, many are still unaware of the services we provide. Even amongst the residents that are familiar with us, some of the services available remain unknown, especially our identification and diagnostic services. Here’s a rundown on some of the services available through your UF/IFAS Extension service.

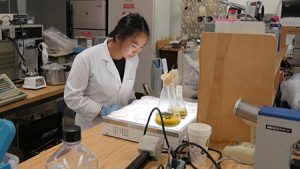

Taking a soil sample. UF/IFAS Photo by Tyler Jones

Soil Testing

This is probably our most well-known service, but it’s worth a reminder. For only $3 (pH only) or $10 (pH plus plant macro- and micro-nutrient values) per sample, plus shipping, you can have your soil analyzed in a state-of-the-art facility. To be clear, soil testing only provides a reading of your soil’s chemistry, specifically pH (acidity/alkalinity) and plant nutrient values. It does not provide information on any diseases or potential toxins that may be present in the soil. In addition to the results, you can specify the general type of plant you’re trying to grow (various grass species, vegetables, citrus, general trees and shrubs, etc.) and the report will provide recommendations to adjust the nutrient levels to be sure that plant is able to thrive. Your local agent receives a copy to help answer any questions you may have about the results or recommendations. More about soil and nutrient testing can be found at the Extension Analytical Services Laboratory website.

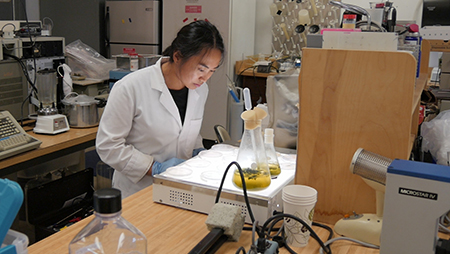

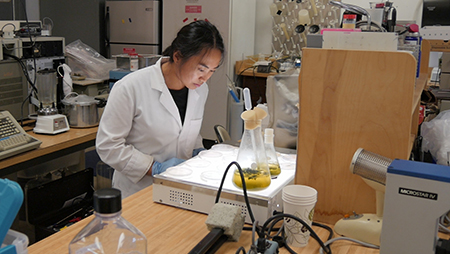

Experts at the Plant Disease Diagnostic Clinic can identify diseases present. Credit: UF/IFAS.

Plant Disease Diagnosis

UF/IFAS Extension has a great plant pathology lab on campus, but we also have a great resource close by in Gadsden County at the North Florida Research and Education Center’s (NFREC) Plant Disease Diagnostic Clinic. For a modest fee of $30, you can submit a sample of a diseased plant, and the lab manager will use the available methods to confirm the presence of disease and identify the disease-causing organism. Just like with the soil test results, you are provided with a recommendation on how to best treat the disease. The NFREC Plant Disease Diagnostic Clinic website has submittal forms, contact information, and directions for collecting a quality sample.

Need help with insect id? The DDIS system can help. Credit: UF/IFAS.

Plant and Insect Identification

While your local extension agent enjoys receiving plant and insect identification, there is an online submittal option available to use as well through our Distance Diagnostic Identification System (DDIS). You can set up an account and then upload photos of plants, insects, mushrooms, even diseased plants, and an expert on UF’s campus will do their best to identify it for you. The DDIS website has more information to help you set up a user account.

The Florida Cooperative Extension Service has many ways to help Florida citizens diagnose their landscape issues using science-based methods conducted by experts in state-of-the-art facilities. The above services are just a selection of the diagnostic capabilities available. To see a complete list, visit the IFAS Diagnostic Services website. You can always contact your local extension office, too, for assistance in identifying plants and insects, as well as diagnosing diseases.

by Donna Arnold | May 22, 2025

Spring and summer bring an explosion of color to gardens, and among the most resilient yet misunderstood flowers are marigolds. Growing up in a small Caribbean town, marigolds were everywhere. Locals called them “Stink and Pretty” or even “graveyard flowers” for their bold scent, but their benefits were undeniable. Whether used in traditional medicine, religious rituals, or tucked into garden beds to keep pests at bay, marigolds have always been more than just a flower.

More Than Just a Bloom

Belonging to the Tagetes genus, marigolds come in a variety of cultivars, each offering unique traits and advantages. Beyond their beauty, they play essential roles in soil conditioning, pest control, especially against nematodes, and companion planting.

A Closer Look at Marigold Varieties

Marigolds fall into distinct categories, each with different growth habits, flower forms, and benefits. The two most common types are Tagetes patula and Tagetes erecta.

- French Marigold (Tagetes patula)

Compact and bursting with warm hues of orange, yellow, and mahogany, French marigolds are excellent pest deterrents. Often planted alongside vegetables, they help manage soil nematodes while thriving in borders and containers.

- African or Perfection Yellow Marigold (Tagetes erecta)

Despite the name “African,” this species hails from Central America. Taller and more dramatic than French marigolds, it produces large, showy golden blooms ideal for cut flowers and mass plantings.

- Signet Marigold (Tagetes tenuifolia)

Delicate foliage, small dainty flowers, and an edible twist—Signet marigolds are a favorite for adding color to salads and attracting pollinators. Plus, their milder scent makes them perfect for gardeners sensitive to stronger fragrances.

A Common Mix-Up

It’s worth noting that while often called “Pot Marigold,” Calendula officinalis is not part of the Tagetes genus. Though it shares similar colors and benefits, calendula is better known for its medicinal properties and edible petals.

Calendula in the Royal Botanical Garden of Madrid, Spain. Photo by Jean-Pierre Dalbéra.

Next time you pass a tray of marigolds at a plant sale or see them brightening a garden bed, take a second look. These unassuming blooms do far more than add beauty—they may just be the unsung heroes of your summer garden.

by Danielle S. Williams | Mar 13, 2025

When most people think of insects, they think of the bad ones, but not all insects are bad! Insects are labeled as bad or ‘pests’ when they start causing harm to people or the things we care about such as plants, animals, and buildings but most insects are GOOD! In fact, of the millions of insect species found throughout the world, less than 2% are actually considered pests. There are several different ways insects can be beneficial in your garden or landscape:

- They prey on pest insects. Many species of insects eat pest insects! For example, lady beetles (ladybugs) and lacewings eat pest insects like aphids, mealybugs and whiteflies. They can help keep insect populations in balance. It’s important to recognize some of the beneficial insect species (and their different life cycle stages) that you might find in your garden. The UF/IFAS Extension bookstore has a great identification guide: Helpful, Harmful, Harmless?

- They parasitize pest insects. Some species of good insects live in or on pest insects. For example, parasitoid wasps lay their eggs into pest insects and when the wasp eggs hatch, they feed on the pest species. Here’s a really great video to show the process: Parasitic Wasps – National Geographic

- They pollinate. Many of the good insects like native bees, honeybees, butterflies and moths help us pollinate our gardens. They transfer pollen grains from flower to flower that help plants bear fruit.

- They decompose. Insects also help aerate our soils by breaking down dead material and recycling nutrients. Dung beetles are a great example! They bury and consume dung which improves soil quality.

One of the best things you can do for your garden is learn to differentiate pest insect species from beneficial ones! Just because you see an insect on your plant, doesn’t necessarily mean it is causing harm. If you see an insect, are you seeing injury to the plant? If so, what type of injury (defoliation, yellowing, leaf curling)? If you aren’t seeing injury, then you may not have anything to worry about. If you find something you’re unsure of, you can always reach out to your local UF/IFAS Extension Agent!

Pipevine swallowtail on Azalea.

Attracting and encouraging beneficial insects can really help your garden and landscape thrive. The best way to attract beneficial insects to your garden or landscape is to have lots of plant diversity. A mix of trees, shrubs, annual and perennial flowers in the landscape is best. Trees and shrubs will provide shelter for insects to overwinter, and flowers provide pollen and nectar.

Flowers in the carrot family (Apiaceae) such as caraway, coriander, cilantro, dill and fennel are attractive for parasitic wasps. Flowers in the Aster family (Asteraceae) such as blanketflower, coneflower, coreopsis, cosmos and goldenrod are attractive for larger predators like lady beetles and soldier beetles. These can be incorporated into the garden or flower beds.

For more information on attracting beneficial insects to your landscape, contact your local UF/IFAS Extension Agent!

by Donna Arnold | Feb 27, 2025

Extension agents occasionally receive calls about “alien” bug sightings, sparking concern among residents. One such insect, Gonatista grisea, commonly known as the Grizzled Mantis, Florida bark Mantis or Lichen Mimic mantis, often raises alarm. But there’s no need to panic—this mantis is a fascinating and harmless part of our ecosystem.

Photo Credit: Vincent Moore, Sweet Magnolia Ridge.

The Grizzled Mantis is native to the United States, ranging from southern Florida to Georgia and South Carolina, and is also found in Puerto Rico, Jamaica, and Cuba. Adults are relatively small, with males measuring 36–38 mm and females slightly larger at 37–40 mm. Their grayish-green coloration and mottled dark markings provide excellent camouflage, allowing them to blend seamlessly into their surroundings, such as lichen-covered bark. They are characterized by triangular heads and large eyes, perfect for their ambush hunting style.

Quick and agile, Grizzled Mantids scuttle rapidly away from perceived threats. They exclusively prey on arthropods, adopting a head-down ambush position while resting on tree bark. Their preferred plants include sea grape, gumbo limbo, water oak, and magnolia, though they are not limited to these species.

Interestingly, mantids are gaining popularity as low-maintenance pets. Some enthusiasts collect egg cases or purchase late-stage nymphs. However, keep in mind that newly hatched mantids require ample food or separation, as they can become cannibalistic if resources are scarce.

Whether in the wild or as pets, the Grizzled Mantis is a unique and beneficial insect, playing a role in controlling arthropod populations. So, the next time you spot one, there’s no need for fear—just appreciation for this remarkable creature!

For more information, contact your local Extension Office or click on the link Grizzled mantid – Gonatista grisea.