by Rick O'Connor | Jul 17, 2015

The air temperatures are in the high ‘90’s and the heat indices are reaching over 100°F; heck the inland water temperatures are in the high ‘80’s – it’s just hot out there! But our barrier island wildlife friends are doing okay, they have had to deal with this many times before. Deep burrows and nocturnal movement lead the list of behavior adaptations to cope but some still scurry around during daylight hours.

People visiting the Gulf coast during the summer.

I typically begin my monthly hikes along the Gulf shore to see what is out and about; this month there were humans… and lots of them. This is the time of year that vacationers visit our islands. Traffic is bad, nowhere to park, long lines, etc. But it is part of living on the Gulf coast. We are glad to have visitors to our part of the state. We do ask that each evening they take their chairs, tents, and trash with them. Have fun.

This plant, Redroot, grows in the wetter areas of the secondary dune.

Seaside Rosemary

During these hot days of summer this flower was blooming all throughout the freshwater bogs of the secondary dunes. The plant is called REDROOT and it is really pretty. I did not see any insects near it but it was in the warm part of the day that I made my hike this month. The round shaped SEASIDE ROSEMARY is one of my favorite plants on the island. The odor it gives off reminds me of camping out there when I was a kid and of the natural beach in general. I have been told that Native Americans did use it when cooking, but can’t verify that. This is a neat plant either way. I believe there are male and female plants in this species and they have a low tolerance of fire and vehicle traffic.

The new, young seeds of the common sea oat.

Though it appears small, this is the same species of pine that grows tall inland.

The most famous plant on our barrier islands is the SEA OAT. However most think of them in the primary dune fields only. They actually grow all across the island as long as their seeds fall in a place where the wind is good, usually at the tops of dunes. As many know the roots and rhizomes of this plant are important in stabilizing the dunes, hence the reason why in most states it is illegal to remove any part of the plant. This PINE is the same type found growing 40 feet up in your yard but here on the beach salt spray and wind stunt their growth. Also the moving sand covers much of the trunk, making the tree appear much smaller than it really is. Pines are quite common on the island.

The tall trees are covered by quartz sand forming the tertiary dune system.

The expanse of marshes that make up Big Sabine on Santa Rosa Island.

The large trees of the barrier island system are typically found in the TERTIARY DUNE field. Here we see pine, oak, and magnolia all growing forming dunes that can reach 50 feet high in some places. Behind large tertiary dunes are the marshes of BIG SABINE. These marsh systems are some of the most biologically productive systems on the planet. 95% of our commercially valuable seafood species spend most, if not all, of their lives here. We will focus on this ecosystem in another edition of this series Discovering the Panhandle.

The red cones of the Sweet bay identify this as a relative of the magnolia.

The “mystery tracks” we have been seeing since January now show the small tracks of a mammal; probably armadillo.

This SWEET BAY is a member of the magnolia family and the small red cones show why. I had not seen the cones until now, so guess they like the heat and rain. WE HAVE SOLVED THE MYSTERY TRACK… knew we would. If you have read the other additions in this series you may recall we have found a track that appeared to be a “slide” coming out of the marsh and into a man-made pond from the old hatchery. Never could determine what was causing this but saw it each month of the year. However this month you could see the individual tracks of a mammal; I am guessing armadillo but could be opossum or raccoon as well. Cool… got that one behind us. On to other discoveries.

Acres and acres of Black Needlerush indicate this is a salt marsh.

Bulrush and other plants indicate that this is not salt water, but a freshwater marsh.

Marshes differ from swamps in that they are predominantly grasses, not trees. Salt marshes, as you would expect, have salt water. Fresh water the opposite… yep. The photo on the left is the salt marsh. The grass species are different and help determine if the water is fresh or brackish. Next year we will do a whole series in this ecosystem – it is pretty cool.

Until next month… enjoy our barrier islands.

by Rick O'Connor | Jul 10, 2015

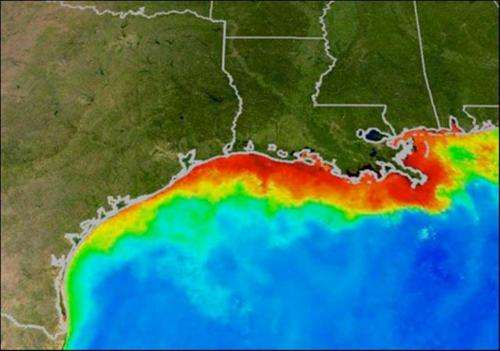

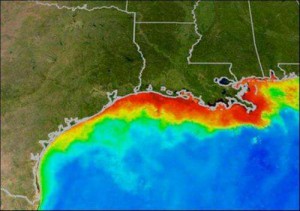

What is the Gulf of Mexico Dead Zone you ask? Well…it’s a layer of hypoxic water (low in dissolved oxygen) on the bottom of the Gulf of Mexico. It was first detected in the 1970’s but reached its peak in size in the 1990’s. The low levels of dissolved oxygen decrease the amount of marine life on the bottom of the Gulf within this zone, including many commercially valuable species supporting the Gulf seafood industry.

The red area indicates where dissolved oxygen levels are low.

What Causes this Dead Zone?

Drops in concentrations of dissolved oxygen within the water column can occur for a variety of reasons but is usually caused by one of two reasons. (1) Increasing water temperatures—as water temperature increases, its ability to hold dissolved oxygen decreases. (2) A process called eutrophication.

What is eutrophication?

Eutrophication is a process where an increase of nutrients in an aquatic system triggers an algal bloom of microscopic phytoplankton. These phytoplankton produce oxygen during the daylight hours but consume it in the evening. Once the bloom dies, decomposing bacteria begin to break them down and consume larger amounts of dissolved oxygen in doing so. When the dissolved oxygen concentrations drop below 2.0 mg/L we say the water is hypoxic and many marine organisms either begin to move out or die. The nutrients that trigger such blooms are primarily nitrates and phosphates. These can be introduced to the water column with plant and animal waste and with synthetically produced fertilizers we use on our fields and lawns. There is natural eutrophication, but when the process is triggered or accelerated by human activity we use the term cultural eutrophication.

So which is it; warming waters or eutrophication?

The Gulf of Mexico Dead Zone usually forms in spring and lasts through September. These are certainly the warmer months of the year, but the warmer waters are near the surface and much of the water column is not warm enough to cause this. Another point is that the Dead Zone is near Louisiana and there are warm locations in other parts of the Gulf where dead zones do not occur. However the Mississippi River does discharge near Louisiana. This river drains 41% of the continental United States, which contains 52% of the nation’s farms. The agricultural waste (plant, animal, and synthetic fertilizers) discharged into the Mississippi River contains nitrogen and phosphorus, the two key nutrients that trigger algal blooms. Based on this, most scientists agree that cultural eutrophication is the primary cause of the Gulf Dead Zone.

When they say it will be a “typical year”, what does that mean – what is a “typical year”?

Scientists from NOAA, the U.S. Geological Survey, and six partnering universities have released their annual forecast of the Dead Zone. The 2015 prediction has the area of the dead zone about equal to the size of Connecticut, which has been the average size for the past several years. This is what they mean by typical.

Can these dead zones occur in our area waters?

Yes, and they do. We do not typically call them “dead zones” but the same process occurs all over the world, including the bays of the Florida panhandle.

What can we do to reduce cultural eutrophication locally?

If you can do without fertilizing your lawn (or field), then do. If this is not an option then only put the amount of fertilizer required for your land/lawn. Most people over fertilize, which not only reduces water quality but is expensive for the property owners. If you can compost your plant waste, do so. With animal waste, please dispose of properly, in a manner where it not reach local waterways.

For more information on hypoxia, eutrophication, and solutions to reduce this problem, contact your county Extension office.

http://www.tulane.edu/~bfleury/envirobio/enviroweb/DeadZone.htm

http://www.iseca.eu/en/science-for-all/what-is-eutrophication

http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/Features/Phytoplankton/

by | Jul 10, 2015

Dodder vines covering an oak seedling. The vines always wrap counterclockwise.

Photo Credit: Jed Dillard

Vampires of all types and genetic modifications are hot topics these days, and a common, but uncommon looking and acting Florida weed may have combined the two subjects. Dodder, a native invasive, parasitic plant, reproduces by seed but does not have enough leaves or chlorophyll to feed itself. Its thin, golden vines and tendrils must attach to a host plant in the seven to ten days it takes the plant to exhaust the carbohydrates in its small seed. Once dodder attaches to a plant, it connects to the inside of the host using small structures called haustoria which press into the stem and begin to draw nutrients from the host. At this point the dodder roots atrophy.

Single dodder plants are not a big issue, but once enough plants build up in an area large mats of vines can reduce growth and vitality of the host. (See photo) Frequently, the pest has reached this stage before it’s noticed, leaving the problem of treating a rootless, nearly leafless plant that is wrapped around a more desirable plant. Not only are the typical routes of herbicidal entry minimized, the hosts are at as much risk as the pest. Hand removal may be practical in small outbreaks, but the plant can reemerge from any small piece left attached to the host. In most cases, the solution is to destroy the host and the dodder and apply a pre-emergent herbicide to stop germination from any seeds remaining in the soil.

What about the GMO angle?

Work published last year in the journal Science by Jim Westwood of Virginia Tech reveals the dodder plant exchanges messenger RNA with tomato and Arabidopsis plants when it extracts the juices from the host plant. Scientists speculate this exchange of genetic material makes the host plant less resistant to attack by the parasite and that this holds promise for learning more about controlling other parasitic plants.

If plants are exchanging messenger RNA, a critical part of protein and gene synthesis, what other genetic exchanges are occurring naturally without our knowledge? Scientific progress hinges on unpredictable events and sources. Learning more from a “vampire weed” that has no easy means of control may be one of those.

To see the dodder plant go from seed to golden mat, watch this time lapse video Virginia Tech has posted on Vimeo. http://www.vtnews.vt.edu/articles/2014/08/081514-cals-talkingplants.html

by Rick O'Connor | Jul 10, 2015

After the recent report of a fatality due to the Vibrio bacteria near Tampa many locals have become concerned about their safety when entering the Gulf of Mexico this time of year. So what are the risks and how do you protect yourself?

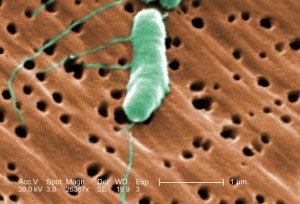

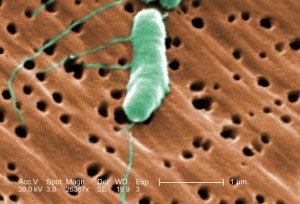

The rod-shaped bacterium known as Vibrio. Courtesy: Florida International University

What is the Flesh Eating Disease Vibrio?

Vibrio vulnificus is a salt-loving rod-shaped bacteria that is common in brackish waters. As with many bacteria, their numbers increase with increasing temperatures. Though the organism can be found year round they tend peak in July and August and remain elevated until temperature decline.

How do people contract Vibrio?

The most common methods of contact with Vibrio are entrance through open wounds exposed to seawater or marine animals and by consuming raw or undercooked shellfish, primarily oysters. The bacterium can also be contracted by eating food that is either served, and has made contact with, raw or undercooked shellfish or the juice of raw or undercooked shellfish.

What is the risk of serious health problems after contracting Vibrio?

Cases of Vibrio infection are rare and the risk of serious health problems is much higher for humans who are have a suppressed or compromised immune system, liver disease or blood disorders such as iron overload (hemochromatosis). Examples include HIV positive, in the process of cancer treatment, and studies show a particularly high risk for those with a chronic liver disease. The Center for Disease Control indicates that humans who are immunocompromised have an 80 times higher chance of serious health issues from Vibrio than healthy people. He also found that most cases involve males over the age of 40. According to the Center for Disease Control there were about 900 cases reported between 1988 and 2006; averaging around 50 cases each year. The Florida Department of Health reported 32 cases of Vibrio infections within Florida in 2014 with 7 of these begin fatal. Five of the cases were in the Florida panhandle but none were fatal. So far this year in Florida there have been 11 cases statewide, 5 of those fatal. Only 1 case was in the panhandle and it was nonfatal. Though 43 cases and 12 fatalities over the last two years in Florida are reasons for concern, when compared to the number of humans who enter marine and brackish water systems every day across the state, the numbers are quite low.

What are the symptoms of Vibrio infection?

For healthy people who consume Vibrio containing shellfish symptoms could include vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. Wounds exposed to seawater that become infected will show redness and swelling. For the at-risk populations described above the bacteria will enter the bloodstream and rapidly cause fever and chills, decreased blood pressure, and blistering skin lesions. For these at-risk population 50% of the cases are fatal and death generally occurs within 48 hours.

It is important that anyone who believes they are at high risk and have the above symptoms that they seek medical attention as quickly as possible.

How can I protect myself from Vibrio infection?

We recommend anyone who has a chronic liver condition, hemochromatosis, or any other immune suppressing medical condition, not consume raw or undercooked filter-feeding shellfish and not enter the water if they have an open wound.

The Center of Disease Control recommends

- If harvesting or purchasing uncooked shellfish do not consume any whose shells are already open

- Keep all shellfish on ice and drain melted ice

- If steaming, do so until the shell opens and then for 9 more minutes

- If frying, do so for 10 minutes at 375°F

- Avoid foods served, and has had contact with, raw or poorly cooked shellfish or that has had contact with raw shellfish juice

- If shucking oysters at a fish house or restaurant, wear protective gloves

It is also important to know that the bacteria does NOT change the appearance or odor of the shellfish product, so you cannot tell by looking at them whether they are good or bad.

For more information on this bacteria visit:

http://www.floridahealth.gov/diseases-and-conditions/vibrio-infections/vibrio-vulnificus/

http://www.cdc.gov/vibrio/vibriov.html