by Sheila Dunning | Jan 19, 2018

The Florida Master Naturalist Program is an adult education University of Florida/IFAS Extension program. Training will benefit persons interested in learning more about Florida’s environment or wishing to increase their knowledge for use in education programs as volunteers, employees, ecotourism guides, and others.

The Florida Master Naturalist Program is an adult education University of Florida/IFAS Extension program. Training will benefit persons interested in learning more about Florida’s environment or wishing to increase their knowledge for use in education programs as volunteers, employees, ecotourism guides, and others.

Through classroom, field trip, and practical experience, each module provides instruction on the general ecology, habitats, vegetation types, wildlife, and conservation issues of Coastal, Freshwater and Upland systems. Additional special topics focus on Conservation Science, Environmental Interpretation, Habitat Evaluation, Wildlife Monitoring and Coastal Restoration. For more information go to: http://www.masternaturalist.ifas.ufl.edu/ Okaloosa and Walton Counties will be offering Upland Systems on Thursdays from February 15- March 22. Topics discussed include Hardwood Forests, Pinelands, Scrub, Dry Prairie, Rangelands and Urban Green Spaces. The program also addresses society’s role in uplands, develops naturalist interpretation skills, and discusses environmental ethics. Check the website for a Course Offering near you :http://conference.ifas.ufl.edu/fmnp/

by Andrea Albertin | Jan 19, 2018

A poultry farm in North Florida used FDACS cost share funds to install solar panels for renewable energy production. Photo source: FDACS Office of Energy

Maximize your farm’s energy savings with FDACS’ free energy evaluations and cost share program

The Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services (FDACS) Office of Energy is currently offering free energy evaluations and cost share funds to increase on-farm energy efficiency to agricultural producers in Florida. This includes all types of operations, such as row crop, fruit and vegetable farms, nurseries, livestock and poultry operations, dairies, and aquaculture farms.

What is an energy evaluation and how is it done?

The purpose of the free evaluations (which are valued at $4,500) is to let producers know how they can maximize energy efficiency and ultimately reduce costs on-farm. During these evaluations, members of a Mobile Energy Lab (MEL) walk through the operation with the producer, evaluating all forms of energy use. Since energy use is often linked to water use (irrigation pivots, for example), the team also assesses water use.

MEL teams are made up of energy experts contracted by FDACS from one of three universities: Florida A&M University, the University of Central Florida and the University of Florida. The MEL will be made up of members from the university closest to the farming operation being evaluated.

After the MEL team has finished the on-site visit, it prepares an evaluation and sends it to the producer. The evaluation details energy use and makes recommendations about how to increase efficiency on-farm. These recommendations depend on the operation and what the farmer is interested in doing. They can include switching to more efficient lighting, converting irrigation pumps from diesel to electric, using variable frequency drives (VFDs) on milk vacuum pumps in dairy operations and switching to or adding small-scale renewable energy generation, like solar or biomass, among others.

After a producer decides on changes she or he would like to make, FDACS offers 80% reimbursement (or cost-share) up to $25,000 to implement recommendations made in the evaluation.

An additional advantage of having a free energy evaluation completed by the MEL is that the evaluation can be used to apply for cost share funds from the USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP). Producers could potentially receive cost share dollars from both FDACS and NRCS to increase on-farm energy efficiency.

A producer in the Suwanee Valley took advantage of cost share funds to switch from using a diesel irrigation pump (left) to an electric pump (right). Photo source: FDACS Office of Energy

What is the timeframe for applying for energy evaluations and cost share funds?

FDACS offers statewide evaluations and cost share through their FRED Program (Farm Renewable and Efficiency Demonstration). These funds are set to expire September 2018, and so any items or equipment obtained with cost share funds must be purchased and installed by September 2018.

To have enough time to apply for and receive an energy evaluation (which is the first step to obtaining cost share funds), applications for evaluations must be turned in to FDACS by February 1, 2018.

The good news is that a similar program will continue after September. However, it will be in a more geographically restricted area. The Office of Energy received BP RESTORE funds to continue funding energy evaluations and cost share in the Apalachicola and Suwannee River Basins. These funds will be available starting this spring. The office hopes to secure more RESTORE funds in the future to expand the geographic reach of the program.

It’s estimated that dairy farms with 50 cows or more could save 40-55% of milk vacuum pump costs by using a variable frequency drive or variable speed drive (VFD) (shown above) on milk vacuum pumps. Photo source: FDACS Office of Energy

Who is eligible for energy evaluations and cost share funds?

Producers that are eligible for NRCS EQIP funds are eligible for this energy program. As stated by FDACS, this means a producer has to:

- Have control of the land for the term of the proposed contract period.

- Be in compliance with the highly erodible land and wetland conservation provisions described in 7 CFR (Code of Federal Regulations) Part 12.

- Have an interest in the agricultural operation as defined in 7 CFR Part 1400.

- The average adjusted gross income of the individual, joint operation or legal entity, may not exceed $900,000

If you have any questions about these requirements, please contact Takara Waller at the Office of Energy (contact information listed below).

How do you apply for an energy evaluation?

To apply for an energy evaluation, you need to submit an application to the FDACS Office of Energy. Application forms and instructions on how to submit them, as well as more information about the program can be found at http://www.freshfromflorida.com/Business-Services/Energy/Incentives-for-Agriculture-Producers

If you have any questions, Takara Waller from the Office of Energy can help guide you through the process. Her contact information is:

(850) 617-7470 (phone)

(850) 617- 7471 (fax)

Takara.Waller@FreshFromFlorida.com

For more information about NRCS EQIP cost share funds, contact your local NRCS office. Contact information for offices in the panhandle region can be found at https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/detail/fl/contact/local/?cid=nrcs141p2_015022

Your local USDA Farm Services Agency can also provide more information about cost share programs related to energy. Contact information by county is found by selecting (or clicking on) the county of interest on the following map https://offices.sc.egov.usda.gov/locator/app?service=page/CountyMap&state=FL&stateName=Florida&stateCode=12.

Remember: an energy evaluation is the first step in obtaining cost share funds to increase on-farm energy efficiency and savings.

by Sheila Dunning | Jan 19, 2018

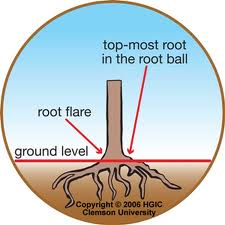

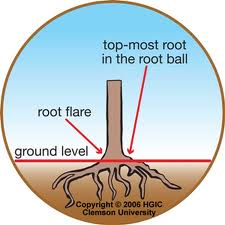

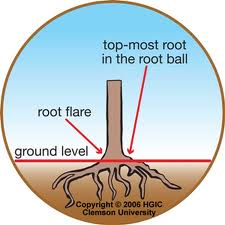

We plant trees with the intention of them being there long after we are gone. However, m any trees and shrubs fail before ever reaching maturity. Often this is due to improper installation and establishment. Research has shown that there are techniques to improve survivability. Before digging the hole:

any trees and shrubs fail before ever reaching maturity. Often this is due to improper installation and establishment. Research has shown that there are techniques to improve survivability. Before digging the hole:

- Look up. If there is a wire, security light, or building nearby that could interfere with proper development as it grows, plant elsewhere.

- Dig a shallow planting hole as wide as possible. Shallow is better than deep! Many people plant trees too deep. A hole about one-and-one-half the diameter of the width of the root ball is recommended. Wider holes should be used for compacted soil and wet sites. In most instances, the depth of the hole should be LESS than the height of the root ball, especially in compacted or wet soil. If the hole was inadvertently dug too deep, add soil and compact it firmly with your foot. .

- Find the point where the top-most root emerges from the trunk. If this is buried in the root ball then remove enough soil from the top so the point where the top-most root emerges from the trunk is at the surface. Burlap on top of the ball may have to be removed to locate the top root.

- Slide the plant carefully into the planting hole. To avoid damage when setting a large tree in the hole, lift the tree with straps or rope around the root ball, not by the trunk. Special strapping mechanisms need to be constructed to carefully lift trees out of large containers.

- Position the plant where the top-most root emerges from the trunk slightly above the landscape soil surface. It is better to plant a little high than to plant it too deep. Remove most of the soil and roots from on top of the root flare and any growing around the trunk or circling the root ball. Once the root flare is at the appropriate depth, pack soil around the root ball to stabilize it. Soil amendments are usually of no benefit. The soil removed from the hole and from on top of the root ball makes the best backfill unless the soil is terrible or contaminated. Insert a square-tipped balling shovel into the root ball tangent to the trunk to remove the entire outside periphery. This removes all circling and descending roots on the outside edge of the root ball.

- Straighten the plant in the hole. Before you begin backfilling have someone view the plant from two directions perpendicular to each other to confirm that it is straight. Break up compacted soil in a large area around the plant provides the newly emerging roots room to expand into loose soil. This will hasten root growth translating into quicker establishment Fill in with some more backfill soil to secure the plant in the upright position.

- Remove synthetic materials from around trunk and root ball. Synthetic burlap needs to be completely removed from the root ball; treated burlap can be left in place. String, strapping, plastic, and other materials that will not decompose and must be removed from the trunk at planting. Remove the wire above the soil surface from wire baskets before backfilling.

- Apply a 3-inch-layer of mulch. To retain moisture and suppress weeds cover the outer half of the root ball with an organic mulch. Do not cover the stem of the plant or the connecting root flare.

- Water consistently until established. For nursery stock less than 2-inches in caliper, this will require every other day for 2 months, followed by weekly 3-4 months. At each irrigation, apply 2 to 3 gallons of water per inch trunk caliper directly over the root ball. Never add irrigation if the ground is saturated.

by Rick O'Connor | Jan 19, 2018

In the last article, we discussed what phytoplankton are, what their needs were, and their importance to marine life throughout the Gulf and coastal estuaries. In this article, we will discuss the different types of phytoplankton found in our waters.

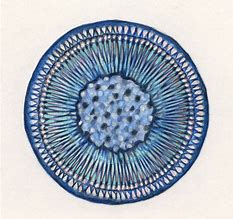

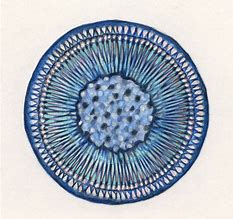

The spherical shape of the centric diatom.

Image: Florida International University

Marine scientists interested in the diversity and abundance of phytoplankton will typically sample using a plankton net. There are a variety of different shapes and sizes of these nets, but the basic design would be funnel shaped with a sample jar attached at the small end of the funnel. The plankton net would be towed behind the research vessel at varying depths for a set period of time. All plankton collected would be analyzed via a microscope. According to the text Identifying Marine Phytoplankton (1997) there are at least 14,000 species of phytoplankton and some suggest as many as 120,000. Most of these, 12,000-100,000, are diatoms, one of five classes of marine phytoplankton. The majority of the phytoplankton fall into one of two class, the diatoms and the dinoflagellates.

Diatoms are typically single celled algae encased in a clear silica shell called a frustule. The frustule can come in a variety of shapes, with or without spines, and many resemble snowflakes – their quite beautiful. They are found in the bay and Gulf in great numbers, as many as 40,000,000 cells / cup of seawater. They are the dominate phytoplankton in colder waters and are most abundant near upwellings. These are the “grasses of the sea” and the base of many marine food webs. When diatoms die, their silica shells sink to the seafloor forming layers of diatomaceous earth, which is used in filters for aquariums and oxygen mask in hospitals.

Dinoflagellates differ from diatoms in that they produce two flagella, small hair-like projections from the algae that are used for generating water currents and movement. Their shells are not silica but layers of membranes and are called thecas. Some membranes are empty and others contain different types of polysaccharides. Dinoflagellates are more abundant than diatoms in warmer waters. There are about 2000 species of them. One type, Noctiluca, are responsible for what locals call “phosphorus” or bioluminescence. These dinoflagellates produce a blue-ish light when disturbed. Many see this when walking the beach at night. Their footprints glow for a few seconds. At night, boaters can see this as their prop wash turns the dinoflagellates in the water column. The bioluminescence is more pronounced in the warm summer months and is believed to be defense against predation. The light is referred to as “cool” light in that the majority of the energy is used in producing light, not lost as heat as with typical incandescent bulbs – hence the birth of the LED light industry.

The dinoflagellate Karenia brevis.

Photo: Smithsonian Marine Station-Ft. Pierce FL

Several dinoflagellates produce toxins as a defense. Some generate what we call red tides. In the Gulf of Mexico, Karenia brevis is the species most responsible for red tide. Red tides typical form offshore and are blown into coastal areas via wind and currents. They are common off the coast of southwest Florida but occur occasionally in the panhandle. Many local red tides are actually formed in southwest Florida and pushed northward via currents. Red tides are known to kill marine mammals and fish, as well as closing areas for shellfish harvesting.

Like true plants, phytoplankton conduct photosynthesis. Between the diatoms and dinoflagellates, 50% of the planet’s oxygen is produced. These are truly important players in the ecology of both the open Gulf and local bays.

References

Annett, A.L., D.S. Carson, X. Crosta, A. Clarke, R.S. Ganeshram. 2010. Seasonal Progression of Diatom

Assemblages in Surface Waters of Ryder Bay, Antarctica. Polar Biology vol 33. Pp. 13-29.

Hasle, G.R., E.E. Syvertsen. 1997. Identifying Marine Phytoplankton. Academic Press Harcourt Brace and

Company. San Diego CA. edited by C.R. Tomas. Pp. 858.

Steidinger, K.A., K. Tangen. 1997. Identifying Marine Phytoplankton. Academic Press Harcourt Brace and

Company. San Diego CA. edited by C.R. Tomas. Pp. 858.

by Les Harrison | Jan 5, 2018

St. Marks River Preserve State Park is still being developed, but open for native habitat enthusiast and those who enjoy this environment as nature established it.

Located along the banks of the St. Marks River’s headwaters, this park offers an extensive system of trails for hiking, horseback riding, and off-road bicycling. The existing road network in the park takes visitors through upland pine forests, hardwood thickets and natural plant communities along the northern banks of the river.

The St. Marks River is not navigable within the park boundaries. It is not conducive to canoeing or kayaking unless visitors are willing to accept long portages through thick undergrowth.

Most of the trails are dry and sandy, but plan for the low water crossings which some of the trails traverse. The rainy months of summer increase the prospects of water crossings.

This preserve is home to a wide variety of native fauna including black bear, deer, turkey and much more. Wildlife tracks frequently crisscross the park’s roads and trails.

At the northern end of the park two sections have had timber removed. One plot has been replanted with wiregrass seed which should germinate this year. Both areas have been planted with long-leafed pine seedlings.

This preserve offers avian aficionados the opportunity to witness nature at its finest as birds fill the air with their calls. A wide assortment of residential and migratory birds can be viewed in their natural habitat.

There are currently no amenities available at the park and it does not have restroom facilities. Additionally, visitors must bring in water for themselves or their horse.

There are no fees presently required to enjoy this gem of a park. Located east of Tallahassee, it is 3.5 miles east of W.W. Kelly Road on Tram Rd (Leon County Highway 259) almost to the Jefferson County line.

Adequate planning should be made to pack in and pack out all needed items for the day. The nearest convenience stores are located in Wacissa a few miles west of the park on Tram Road.

The Florida Master Naturalist Program is an adult education University of Florida/IFAS Extension program. Training will benefit persons interested in learning more about Florida’s environment or wishing to increase their knowledge for use in education programs as volunteers, employees, ecotourism guides, and others.

The Florida Master Naturalist Program is an adult education University of Florida/IFAS Extension program. Training will benefit persons interested in learning more about Florida’s environment or wishing to increase their knowledge for use in education programs as volunteers, employees, ecotourism guides, and others.