by Rick O'Connor | May 31, 2018

It is now late May and in recent weeks I, and several volunteers, have been surveying the area for terrapins, horseshoe crabs, and monitoring local seagrass beds. We see many creatures when we are out and about; one that has been quite common all over the bay has been the “stingray”.

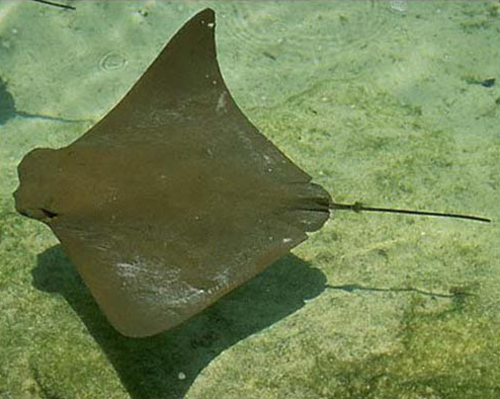

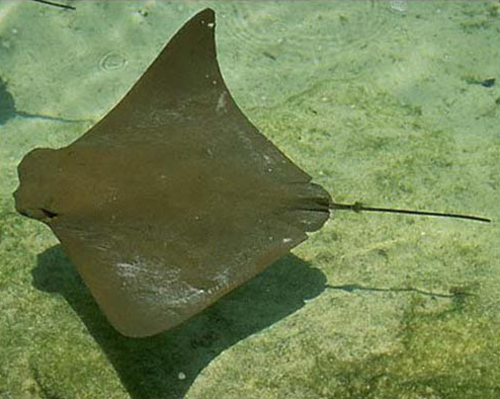

The cownose ray is often mistaken for the manta ray. It lacks the palps (“horns”) found on the manta.

Photo: Florida Sea Grant

These are intimidating creatures… everyone knows how they can inflict a painful wound using the spine in their tail, but may are not aware that not all “stingrays” can actually use a spine to drive you off – actually, not all “rays” are “stingrays”.

So what is a ray?

First, they are fish – but differ from most fish in that they lack a bony skeleton. Rather it is cartilaginous, which makes them close cousins of the sharks.

So what is the difference between a shark and a ray?

You would immediately jump on the fact that rays are flat disked-shape fish, and that sharks are more tube-shaped and fish like. This is probably true in most cases, but not all. The characteristics that separate the two groups are

- The five gill slits of a shark are on the side of the head – they are on the ventral side (underside) of a ray

- The pectoral fin begins behind the gill slits in sharks, in front of for the ray group

Not all rays have the whip-like tail that possess a sharp spine; some in fact have a tube-shaped body with a well-developed caudal fin for a tail.

There are eight families and 19 species of rays found in the Gulf of Mexico. Some are not common, but others are very much so.

Sawfish are large tube-shaped rays with a well-developed caudal fin. They are easily recognized by their large rostrum possessing “teeth” giving them their common name. Walking the halls of Sacred Heart Hospital in Pensacola, you will see photos of fishermen posing next to monsters they have captured. Sawfish can reach lengths of 18 feet… truly intimidating. However, they are very slow and lethargic fish. They spend their lives in estuaries, rarely going deeper than 30 feet. They were easy targets for fishermen who displayed them as if they caught a true monster. Today they are difficult to find and are protected. There are still sightings in southwest Florida, and reports from our area, but I have never seen one here. I sure hope to one day. There are two species in the Gulf of Mexico.

Guitarfish are tube-shaped rays that are very elongated. They appear to be sharks, albeit their heads are pretty flat. They more common in the Gulf than the bay and, at times, will congregate near our reefs and fishing piers to breed. They are often confused with the electric rays called torpedo rays, but guitarfish lack the organs needed to deliver an electric shock. They have rounded teeth and prefer crustaceans and mollusk to fish. There is only one species in the Gulf.

Torpedo rays can deliver an electric shock – about 35 volts of one. Though there are stories of these shocking folks to death, I am not aware of any fatalities. Nonetheless, the shock can be serious and beach goers are warned to be cautious. I once mistook one buried in the sand for a shell. Let us just say the jolt got my attention and I may have had a few words for this fish before I returned to the beach. We have two species of torpedo rays in the Gulf of Mexico.

Skates look JUST like stingrays – but they lack the whip-like tail and the venomous spine that goes with it. They are very common in the inshore waters of the Florida Panhandle and though they lack the terrifying spine we are all concerned about, they do possess a series of small thorn-like spine on the back that can be painful to the bare foot of a swimmer. Skates are famous for producing the black egg case folks call the “mermaids’ purse”. These are often found dried up along the shore of both the Gulf and they bay and popular items to take home after a fun day at the beach. There are four species of skates found in the Gulf of Mexico.

Stingrays… this is the one… this is the one we are concerned about. Stingrays can be found on both sides of our barrier islands and like to hide beneath the sand to ambush their prey. More often than not, when we approach they detect this and leave. However, sometimes they will remain in the sand hoping not to be detected. The swimmer then steps on their backs forcing them to whip their long tail over and drive the serrated spine into your foot. This usually makes you move off them – among other things. The piercing is painful and spine (which is actually a modified tooth) possesses glands that contain a toxic substance. It really is no fun to be stung by these guys. Many people will do what is called the “stingray shuffle” as they move through the water. This is basically sliding your feet across the sand reducing your chance of stepping on one. They are no stranger to folks who visit St. Joe Bay. The spines being modified teeth can be easily replaced after lodging in your foot. Actually, it is not uncommon to find one with two or three spines in their tails ready to go. Stingrays do not produce “mermaids’ purses” but rather give live birth. There are five species in the Gulf of Mexico.

The Atlantic Stingray is one of the common members of the ray group who does possess a venomous spine.

Photo: Florida Museum of Natural History

Butterfly ray is a strange looking fish and easy to recognize. The wide pectoral fins and small tail gives it the appearance of a butterfly. Despite the small tail, it does possess a spine. However, the small tail makes it difficult for the butterfly ray to pierce you with it. There is only one species in the Gulf, the smooth butterfly ray.

Eagle rays are one of the few groups of rays that actually in the middle of the water column instead of sitting on the ocean floor. They can get quite large and often mistaken for manta rays. Eagle rays lack the palps (“horns”) that the manta ray possesses. Rather they have a blunt shaped head and feed on mollusk. They do have venomous spines but, as with the butterfly ray, their tails are too short to extend and use it the way stingrays do. There are two species. The eagle ray is brown and has spots all over its back. The cownose ray is very common and almost every time I see one, I hear “there go manta rays”… again, they are not mantas. They have a habit of swimming in the surf and literally body surfing. Surfers, beachcombers, and fishermen frequently see them.

Last but not least is the very large Manta ray. This large beast can reach 22 feet from wingtip to wing tip. Like eagle rays, they swim through the ocean rather than sit on the bottom. They have to large “horns” (called palps) that help funnel plankton into their mouths. These horns give them one of their common names – the devilfish. Mantas, like eagle and butterfly rays, do have whip-like tails and a venomous spine, but like the above, their tails are much shorter and so effective placement of the spine in your foot is difficult.

Many are concerned when they see rays – thinking that all can inflict a painful spine into your foot – but they are actually really neat animals, and many are very excited to see them.

References

Hoese, H.D., R.H. Moore. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M. College Station, TX. pp. 327.

Shipp, R. L. 2012. Guide to Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico. KME Seabooks. Mobile AL. pp. 250.

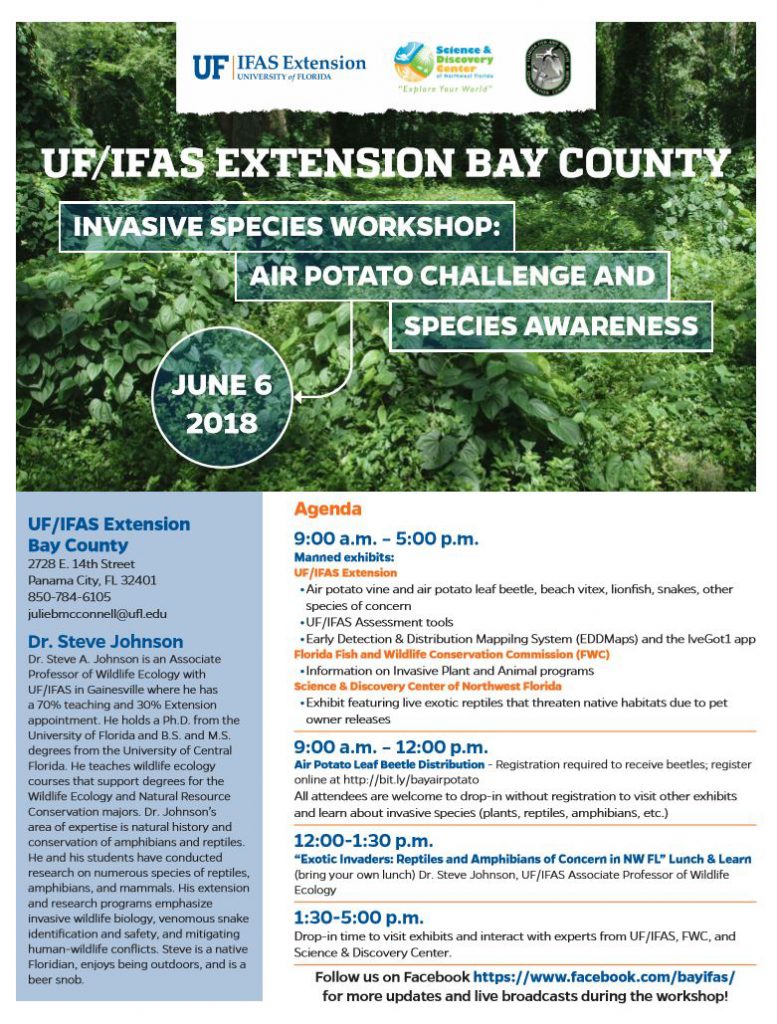

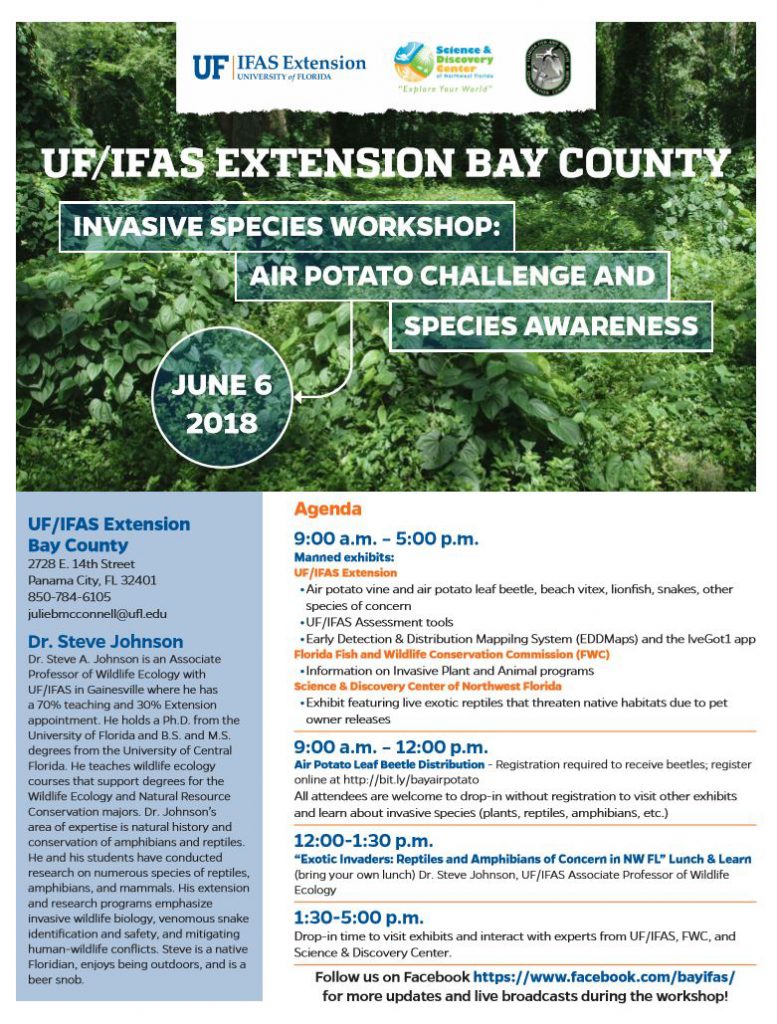

by Scott Jackson | May 25, 2018

By L. Scott Jackson and Julie B. McConnell, UF/IFAS Extension Bay County

Northwest Florida’s pristine natural world is being threaten by a group of non-native plants and animals known collectively as invasive species. Exotic invasive species originate from other continents and have adverse impacts on our native habitats and species. Many of these problem non-natives have nothing to keep them in check since there’s nothing that eats or preys on them in their “new world”. One of the most problematic and widespread invasive plants we have in our local area is air potato vine.

Air potato vine originated in Asia and Africa. It was brought to Florida in the early 1900s. People moved this plant with them using it for food and traditional medicine. However, raw forms of air potato are toxic and consumption is not recommended. This quick growing vine reproduces from tubers or “potatoes”. The potato drops from the vine and grows into the soil to start new vines. Air potato is especially a problem in disturbed areas like utility easements, which can provide easy entry into forests. Significant tree damage can occur in areas with heavy air potato infestation because vines can entirely cover large trees. Some sources report vine growth rates up to eight inches per day!

Air Potato vines covering native shrubs and trees in Bay County, Florida. (Photo by L. Scott Jackson)

Mechanical removal of vines and potatoes from the soil is one control method. Additionally, herbicides are often used to remediate areas dominated by air potato vine but this runs the risk of affecting non-target plants underneath the vine. A new tool for control was introduced to Florida in 2011, the air potato leaf beetle. Air potato beetle releases have been monitored and evaluated by United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) researchers and scientists for several years.

Air Potato Beetle crawling on leaf stem. Beetles eat leaves curtailing the growth and impact of air potato. (Photo by Julie B. McConnell)

Air potato beetles target only air potato leaves making them a perfect candidate for biological control. Biological controls aid in the management of target invasive species. Complete eradication is not expected, however suppression and reduced spread of air potato vine is realistic.

UF/IFAS Extension Bay County will host the Air Potato Challenge on June 6, 2018. Citizen scientist will receive air potato beetles and training regarding introduction of beetles into their private property infested with air potato vine. Pre-registration is recommended to receive the air potato beetles. Please visit http://bit.ly/bayairpotato

In conjunction with the Air Potato Challenge, UF/IFAS Extension Bay County will be hosting an invasive species awareness workshop. Dr. Steve Johnson, UF/IFAS Associate Professor of Wildlife Ecology, will be presenting “Exotic Invaders: Reptiles and Amphibians of Concern in Northwest Florida”. Additionally, experts from UF/IFAS Extension, Florida Fish and Wildlife, and the Science and Discovery center will have live exhibits featuring invasive reptiles, lionfish, and plants. For more information visit http://bay.ifas.ufl.edu or call the UF/IFAS Extension Bay County Office at 850-784-6105.

Flyer for Air Potato Challenge and Invasive Species Workshop June 6 2018

by Rick O'Connor | May 25, 2018

In the mid 1990’s, the Bay Area Resource Council was created. This multi-county (Escambia and Santa Rosa) organization included local scientists and decision makers to help better understand the health of Pensacola Bay, develop a plan for restoration, and work collaboratively to acquire funding to do so. At the inaugural meeting, many different scientists spoke on a variety of topics. There were several take-home messages – one of them was that sediments of Pensacola Bay were in poorer health than the water within the water column above it.

Grabs are used by marine scientist to collect samples of sediments from the bottom of the bay.

Photo: Coastal Science NOAA

So, what is wrong with the sediments, and how has this changed since the mid ‘90’s?

Based on sediment sample analysis, some researchers consider the Pensacola Bay System the most polluted in the state of Florida… but not everyone. The three bayous (Chico, Texar, and Grande), Escambia Bay, and the downtown waterfront of Pensacola Bay had some of the poorest sediment samples within the system. Contaminants monitored include trace metals, mercury, non-nutrient organics, pesticides, and dioxins. These contaminants are dense and do not remain in the water column long. Instead, they sink into the sediments. At that time, some suggested that attempts to remove the contaminants could increase their levels within the water column and do more harm than good – thinking it would be better to leave the sediments as they are. Many of the compounds entered the estuary through run-off. In some cases in the past, they were discharged directly into a bay or river.

Chemicals found in Pensacola estuarine sediments include Arsenic, Zinc, and Copper. Mercury levels at some locations in the bay are higher than other estuaries around the northern Gulf region. Some non-nutrient organic compounds were not as high as other local estuaries however; bioaccumulation (the increase in contaminant concentrations via the food chain) has been occurring and should be monitored. Many chemical compounds banned in the 1970’s have long half-lives and are still detected in the sediments today. Chlorinated pesticides, such as dieldrin, chlordane, DDE, DDD, and DDT are still found in the bayous – and at higher concentrations than neighboring estuaries.

This all sounds bad, but are the levels high enough to be toxic to marine organisms?

Herbicides and pesticides can find their way into estuarine systems and contaminate the sediments.

Photo: UF IFAS Washington County Extension

One location, in upper Bayou Texar, seems to be quite toxic to the species of bacteria, invertebrates, fish, and plants tested. These toxic concentrations are partially from chemicals present in run-off, but there is also seepage coming from groundwater contaminated from a nearby Superfund site. Most of the test suggest that the lethal concentrations are more chronic in nature than acute.

So what can be done? What can we do?

Well… removing and treating these sediments is quite expensive and is not an option at this time. There are plans to dredge portions of Bayou Chico but the process has undergone extensive scrutiny and permitting. One thing we can do is reduce the amount that is still entering the bay. How do we do this?

- Consider re-landscaping your yard to be “Florida Friendly”. Using the suggestions given within this University of Florida program (http://fyn.ifas.ufl.edu/) you can reduce the amount of fertilizer, herbicide, and pesticides you use – thus reducing the amount entering the estuaries.

- Florida Friendly Landscaping practices can also reduce the amount of watering your lawn needs. This reduces the amount of run-off reaching the bay and always reduces the amount of money you spend on watering and lawn chemicals.

- The Florida Department of Environmental Protection’s Clean Boater program provides tips and suggestions that reduce the amount of hazardous chemicals that enter the bay from cleaning and maintaining vessels. https://floridadep.gov/fco/cva/content/clean-boater-program.

The sediments of the bay have suffered the abuse of the past. However, with better practices, we can reduce our impact in the future.

Florida Friendly Landscaping saves money and reduces our impact on the estuarine environment.

Photo: UF IFAS

Reference

Lewis, M.J., J.T. Kirschenfeld, T. Goodhart. 2016. Environmental Quality of the Pensacola Bay System: Retrospective Review for Future Resource Management and Rehabilitation. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Gulf Breeze FL. EPA/600/R-16/169.

by Rick O'Connor | May 25, 2018

In recent weeks, volunteers and I have been surveying local estuaries counting terrapins, horseshoe crabs, and monitoring seagrass. One animal that has been very visible during these surveys is the relatively large snail known as the crown conch (Melongena corona). Its shell is often found with a striped hermit crab living within, but it is actually produced by a fleshy snail, who is a predator to those slow enough for it to catch.

The white spines along the whorl give this snail its common name – crown conch.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

The shell is familiar to most who venture to the estuary side of our beaches. Reaching around five inches in length, crown conch shells are spiral with a wide aperture (opening) and brown to purple to white in color. Each whorl ends with white spins giving it the appearance of a crown and – hence – it’s common name. They are typically seen cruising along the sediments near grassbeds, salt marshes and oyster reefs – their long black siphons extended drawing in seawater for oxygen, but also to detect scents that will lead them to food.

These snails breed from winter to early summer. Females, larger than males, will develop 15-500 eggs in capsules, which they attach to hard structures within the habitat; such as wood, seagrass blades, and shell material.

Crown conchs are subtropical species and have a low tolerance for cold water. They are common in the panhandle and may expand further north along the Atlantic coast if warming trends continue. They have a higher tolerance for changes in salinity and can tolerate salinity as low as 8 ppt. The salinities within Pensacola Bay can be as low as 10 ppt and Santa Rosa Sound / Big Lagoon are typically between 20-30 ppt. The developing young require higher salinities and thus breeding takes in the lower portions of our estuaries.

These are guys are snail predators – seeking prey slow enough for them to catch. Common targets include the bivalves such as oysters and clams, but they are known to seek out other snails – like whelks. Crown conchs are known to feed on dead organisms they encounter and may be cannibalistic. As with all creatures, they have their predators as well. The large thick shell protects them from most but other snails, such as whelks and murex, are known predators of the crown conch.

These conchs tend to stay closer to shallow water (less than 3 ft.) due the large number of predators at depth. They are common in seagrass meadows and salt marshes and – if in high numbers with few competitors – have been considered an indicator of poor water quality. There is no economic market for them but they are monitored due to the fact they affect the populations of commercially important oysters and clams.

The “snorkel” is called a siphon and is used by the snail to draw water into the mantle cavity. Here it can extract oxygen and detect the scent of prey.

Photo: Franklin County Extension

It is an interesting animal, a sort of “jaws” of the snail world, and a possible candidate for a citizen science water quality monitoring project. Enjoy exploring your coastal estuaries this summer and discover some of these interesting animals.

Reference

Masterson, J. 2008. Indian River Lagoon Species Inventory: Crown Conch Melongena corona. Smithsonian Marine Station at Ft. Pierce, Florida. http://www.sms.si.edu/irlspec/Melongena_corona.htm.

by Ray Bodrey | May 23, 2018

Storm Season is Right Around the Corner, Let’s Be Ready

Ray Bodrey, UF/IFAS Gulf County Extension Director

Hurricane season technically begins on June 1st and ends November 30th. However, storm season may reach us in the Panhandle as early as Memorial Day weekend. As Floridians, we face the possibility of tropical storms and hurricanes every year. This simply goes with the territory. During these months, it’s important to have a safety plan in place.

Be sure to keep a basic emergency kit in your home, even for storms that may not require you to evacuate. This kit should have at least the following supplies:

- battery powered NOAA weather radio

- extra batteries

- flashlight

- whistle

- manual can opener

- food and water

- moist towelettes

- first aid kit. The kit should have enough supplies for at least three days.

If the approaching storm is a major threat, you may be asked to leave your home. State & County emergency management officials would not ask you to do so without a valid reason. Please do not second guess this request. Leave your home immediately. Requests of this magnitude will normally come through radio broadcasts and area TV stations.

UF/IFAS photo: Marisol Amador

The most important thing to keep in mind if a major storm is approaching is to have your own plan for a possible evacuation. The University of Florida has developed, “The Disaster Handbook” to help citizens plan for safety. The handbook includes a chapter dedicated to hurricane planning. The chapter can be downloaded in pdf at http://disaster.ifas.ufl.edu/chap7fr.htm.

Utilizing the 15 principles below will assist you in your evacuation planning efforts:

-Know the route & directions: keep a paper state map in your vehicle. Be prepared to use the routes designated by the emergency management officials.

-Local authorities will guide the public: Stay in communication with local your local emergency management officials. By following their instructions, you are far safer.

-Keep a full gas tank in your vehicle: During a hurricane threat, gas can become sparse. Be sure you fill your tank in advance of the storm.

-One vehicle per household: If evacuation is necessary, take one vehicle. Families that carpool will reduce congestion on evacuation routes.

-Powerlines: Do not go near powerlines, especially if broken or down.

-Clothing: Wear clothing that protects as much area as possible, but suitable for walking in the elements.

-Emergency Kit:This kit should have at least the following supplies: battery powered NOAA weather radio, extra batteries, flashlight, whistle, manual can opener, food, water moist towelettes and first aid kit. The kit should have enough supplies for at least three days.

-Phone: Bring your cell phone & charger.

-Prepare your home before leaving: Lock all windows & doors. Turn off water. You may want to turn off your electricity. If you have a home freezer, you may wish not too. Leave your natural gas on, unless instructed to turn it off. You may need gas for heating or cooking and only a professional can turn it on once it has been turned off.

-Family Communications: Contact family and friends before leaving town, if possible. Have an out of town contact as well, to check in with regarding the storm and safety options.

-Emergency shelters: Know where the emergency shelters are located in your vicinity.

-Shelter in place: This measure is in place for the event that emergency management officials request that you remain in your home or office. Close and lock all window and exterior doors. Turn off all fans and the HVAC system. Close the fireplace damper. Open your disaster kit and make sure the NOAA weather radio is on. Go to an interior room without windows that is ground level. Keep listening to your radio or TV for updates.

-Predetermined meeting place: Have a spot designated for a family meeting before the imminent evacuation. This will help minimize anxiety and confusion and will save time.

-Children at school: Have a plan for picking up children from school and how they will be taken care of and by whom.

-Animals and pets: Have a plan for caring for animals and shelter options in the event of an evacuation. For livestock evacuation, contact your local county extension office

Following these steps will help you stay safe and give you a piece of mind during the storm season. Contact your local county extension office for more information.

Supporting information for this article can be found in the UF/IFAS EDIS publication, “Hurricane Preparation: Evacuating Your Home”, by Elizabeth Bolton & Muthusami Kumaran: http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/FY/FY74700.pdf

For emergency management planning information for individuals and families, please visit the following University of Florida website: https://emergency.ufl.edu/preparedness/emergency-preparedness/ & https://www.ready.gov/build-a-kit

UF/IFAS is An Equal Opportunity Institution.