by Sheila Dunning | Jul 23, 2018

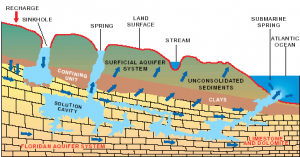

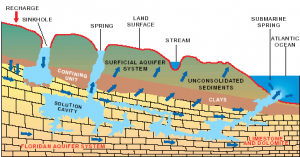

Hydrologic cycle and geologic cross-section image courtesy of Florida Geological Survey Bulletin 31, updated 1984.

With more than 250 crystal clear springs in Northwest Florida it is just a short road trip to a pristine swimming hole! Springs and their associated flowing water bodies provide important habitat for wildlife and plants. Just as importantly, springs provide people with recreational activities and the opportunity to connect with the natural environment. While paddling your kayak, floating in your tube, or just wading in the cool water, think about the majesty of the springs. They are the visible part of the Florida Aquifer, the below ground source of most Florida’s drinking water.

A spring is a natural opening in the Earth where water emerges from the aquifer to the soil surface. The groundwater is under pressure and flows upward to an opening referred to as a spring vent. Once on the surface, the water contributes to the flow of rivers or other waterbodies. Springs range in size from small seeps to massive pools. Each can be measured by their daily gallon output which is classified as a magnitude. First magnitude springs discharge more than 64.6 million gallons of water each day. Florida has over 30 first magnitude springs. Four of them can be found in the Panhandle – Wakulla Springs and the Gainer Springs Group of 3.

Wakulla Springs is located within Edward Ball Wakulla Springs State Park. The spring vent is located beneath a limestone ledge nearly 180 feet below the land surface. Archaeological evidence suggests that humans have utilized the area for nearly 15,000 years. Native Americans referred to the area as “wakulla” meaning “river of the crying bird”. Wakulla was the home of the Limpkin, a rare wading bird with an odd call.

Over 1,000 years ago, Native Americans used another first magnitude spring, the Gainer Springs group that flow into the Econfina River. “Econfina”, or “natural bridge” in the local native language, got its name from a limestone arch that crossed the creek at the mouth of the spring. General Andrew Jackson and his Army reportedly used the natural bridge on their way west exploring North America. In 1821, one of Jackson’s surveyors, William Gainer, returned to the area and established a homestead. Hence, the naming of the waters as Gainer Springs.

Three major springs flow at 124.6 million gallons of water per day from Gainer Springs Group, some of which is bottled by Culligan Water today. Most of the springs along the Econfina maintain a temperature of 70-71°F year-round. If you are in search of something cooler, you may want to try Ponce de Leon Springs or Morrison Springs which flows between 6.46 and 64.6 million gallons a day. They both stay around 67.8°F. Springs are very cool, clear water with such an importance to all living thing; needing appreciation and protection.

by Carrie Stevenson | Jul 23, 2018

Local estuaries are a beautiful place to explore with your family. Credit: Matthew Deitch, UF IFAS Extension

Florida’s rivers, springs, wetlands, and estuaries are central features to the identity of northwest Florida. They provide a wide range of services that benefit peoples’ health and well-being in our region. They create recreational opportunities for swimmers, canoers, and kayakers; support diverse wildlife for birders and plant enthusiasts; sustain a vibrant commercial and recreational fishery and shellfishery; serve as corridors for shipping and transportation; and support ecosystems that help to improve water quality. Maintaining these aquatic ecosystem services requires a low level of chemical inputs from the upstream areas that comprise their watersheds.

Aquatic ecosystems are especially sensitive to nitrogen and phosphorus, which are key nutrients for the growth of plants, algae, and bacteria that live in these waters. High levels of these nutrients combined with our sunny weather and warm summer temperatures create conditions that can lead to rapid growth of aquatic plants and algae, which can cover these water bodies and make them no longer enjoyable for people and wildlife. It can also cause dissolved oxygen levels to fall, as plants respire (especially at night, when they are not photosynthesizing) and as bacteria consume oxygen to break down dead plant material. Low dissolved oxygen can create conditions that are deadly for fish and shellfish.

The Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP) lists more than 1,400 water bodies (including rivers, springs, wetlands, and estuaries) as impaired by pollutants. Many of these are impaired by excessive nitrogen or phosphorus. It is a daunting challenge to reduce pollutants in these water bodies because their inputs frequently come from all over the landscape, rather than a specific point—nutrients can come from agricultural fields, residential landscapes, septic tanks, atmospheric deposition, and livestock throughout the watershed.

In Florida, FDEP has begun a program to reduce nutrient concentrations in impaired watersheds by collaborating with landowners and other stakeholders to develop management programs to reduce pollutants entering the state’s waters. This pollutant reduction program is currently focused on Florida’s spring systems, including Jackson Blue Spring and Merritt’s Mill Pond in Jackson County. Merritt’s Mill Pond is a 4-mile long, 270-acre pond located near Marianna, and it is a popular regional destination for swimming, boating, kayaking, and fishing in the Panhandle. Its main source is Jackson Blue Spring, which produces, on average, more than 70 million gallons of water each day. Excessive growth of aquatic plants and algae in the pond during summer reduces the area available for swimming and boating. In 2014, FDEP began working with agricultural producers, residents, developers, local government officials, and other stakeholders to identify nutrient contributions in the Merritt’s Mill Pond watershed and develop an action plan to reduce nutrients entering the pond in the coming decades. Collaborations with stakeholders help to improve the accuracy of pollutant estimates, and to ensure the plan is designed appropriately to achieve desired ecological outcomes.

This Action Plan for reducing nutrients into Merritt’s Mill Pond provides an opportunity for land managers to implement their own plans to reduce nutrient contributions without FDEP imposing rigid regulations or mandating particular actions. People can choose from an array of Best Management Practices designed to reduce nutrient contributions, and the state has made funds available for people to help implement these plans. Implementing this Action Plan will restore the wonders of Merritt’s Mill through the 21st Century.

This article was written by: Matthew J Deitch, PhD, Assistant Professor, Watershed Management with the UF IFAS Soil and Water Sciences Department at the West Florida Research and Education Center. For more information, you can contact him at mdeitch@ufl.edu or 850-377-2592.

by Rick O'Connor | Jul 6, 2018

The manatee may be one of the more iconic animals in the state of Florida. In Wyoming, we think of bison and bears. In Florida, we think of alligators and manatees. However, encountering this marine mammal in the Florida panhandle is a relatively rare occurrence… until recently.

Manatee swimming in Big Lagoon near Pensacola.

Photo: Marsha Stanton

For several years now, visitors to Wakulla Springs – in the eastern panhandle – have had the pleasure of viewing manatees on a regular basis. It is believed about 40 individuals frequent the river. Last year there were eight individuals that frequent the Perdido Key area, and a couple more were seen more than once near Gulf Breeze. This is not normal for us, but already this year one manatee has been spotted in the Big Lagoon area – so we may be seeing more as the summer goes on.

So what exactly is a manatee?

It is listed as a marine mammal, but frequents both fresh and saltwater habitats. Being mammals, they are warm blooded (endothermic). Maintaining your body temperature internally allows you to live in a variety of cold temperature habitats but water can really draw the heat quickly from anyone’s body. Marine mammals counter this problem by having a thick layer of fat within the skin – insulation called blubber. However, the manatees blubber layer is not very thick. So they are restricted to the tropical parts of the world and, in Florida, spend the winter near warm water springs. Many have learned the trick of hanging out near warm water discharges near power plants. In the warmer months, they venture out to find lush seagrass meadows in which to graze.

They are herbivores. Possessing flat-ridged molars for grinding plant material, they are more closely related to deer and cattle than the seal and walrus they look like. They lack canines and incisors, which deer and cattle use to cut the grass blades, but have large extending lips that grab and tear grasses with – very similar to the trunk of an elephant, which is their closest relative. Like many mammalian herbivores, they grow to a large size. Manatees can reach 15 feet in length and over 1000 pounds. They have two forearms that are paddle shaped and used for steering. The tail is a large circular disk called a fluke, which propels them through the water and is often seen breaking the surface. They are generally slow moving animals but can startle you when they decide to kick into “fourth gear” and burst across the river.

They are generally solitary animals, gathering in the wintertime around the warm springs. Males usually leave the females after breeding and do not form family units, or herds. Females are pregnant for 13 months and typically give birth to one calf, which stays with mom for two years. Like all mammals, the young feed on milk from mammary glands, but these glands are close to the armpits on the manatee. This makes it much easier for the calf to feed while both are swimming. This is not the case with dolphins and whales, where the mother must roll sideways to feed her young.

Manatees hanging out in Wakulla Springs.

Photo provided by Scott Jackson

There are three species of manatees in the world today. The Amazonian Manatee (Trichechus inunguis), the West African Manatee (Trichechus senegalensis) and the West Indie Manatee (Trichechus manatus). The Florida Manatee is a subspecies of the West Indian (Trichechus manatus latirostris). In the 1970’s it was estimated there were about 1000 West Indian manatees left in the word. Today, with the help of numerous nonprofits and state agencies, there is an estimated 6600 in Florida. Due to this increase, the manatee has moved from the federal endangered species list to threatened species. That said, human caused mortality still occurs and boaters should be aware of their presence. Since 2012, an average of 500 manatees die in Florida waters. Most of these are prenatal or undetermined, but about 20% are from boat strikes. Manatees tend stay out of the deeper channels, so boats leaving the ICW for a favorite beach or their dock should keep an eye out. Most of the time they are just below the surface and only their nostrils break for a breath of air. They usually breathe every 3-5 minutes when swimming but can remain below for up to 20 minutes when they are resting. Approaching a manatee is still illegal. Though their status has changed from endangered to threatened, they are still protected by state and federal law.

FWC suggest the following practices for boaters, and PWC, near manatees

- Abide by any speed limit signs – no wake zones

- Wear polarized sunglasses to aid in seeing through the water

- Stay in deeper water and channels as much as possible

- Stay out of seagrass beds – there is are numerous reasons why this is important, not just manatees

- If a manatee is seen, keep your boat/PWC at least 50 feet from the animal.

- Please do not discard your hooks and monofilament into the water – again, numerous reasons why this is a bad practice.

So Why are There More Encounters in the Florida Panhandle?

Good question…

Their original range included the entire northern Gulf coast. When their numbers declined in the 1960’s and 70’s there were fewer animals to venture this far north. Manatee sightings at that time did occur, but were very rare. Today, with increasing numbers, encounters are becoming more common. There is actually a Manatee Watch Program for the Mobile Bay area (https://manatee.disl.org/) and they have been seen as far west as Louisiana.

They are truly neat animals and to see one in our area is a real treat. Remember to view and photo, but do not approach. I hope that many of you will get to meet what maybe new summer neighbors.

Manatee swimming by a pier near Pensacola.

Photo: Marsha Stanton

References

2017 Manatee Mortality Data. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. http://myfwc.com/media/4132460/preliminary.pdf.

Florida Manatee Facts and Information. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. http://myfwc.com/education/wildlife/manatee/facts-and-information/.

Manatee Information for Boaters and PWC. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. http://myfwc.com/education/wildlife/manatee/for-boaters/.

Manatee Sighting Network. https://manatee.disl.org/.

West Indian Manatee. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/West_Indian_manatee.

by Rick O'Connor | Jul 6, 2018

This week’s article is a bit different… it is about nature we hope you DO NOT see – but hope you let us know if you do. Most of you know that Florida, along with many other states, continually battle invasive species. From Burmese pythons, to lionfish, to monitor lizards, we have problems with them all. Many of our invasive species are plants, which grow aggressively and take over habitats. They have few, if any, predators to control their populations and can cause environmental or economic problems for us.

The pretty, but invasive, beach vitex. Photo: Rick O’Connor

The best way to tackle an invasive species is to detect it when it first arrives and remove it as quickly as possible – this provides you the best chance of actually eradicating it from an area at the lowest cost. One such invasive plant that has recently invaded Escambia and Santa Rosa county beaches is Beach Vitex (Vitex rotundifolia).

Beach vitex is a vine that grows along the surface of sandy areas, like dunes. It has a main taproot from which the runners (stolons) extend in a radiating pattern, like a skinny-legged starfish. The stolons will develop secondary roots, which can form smaller deep root systems, and the entire maze of vines grows very quickly in the summer. The leaves are ovate, more round than elongated, and have a grayish-blue-green color to them – they tend to stand out from other plants. The plant can grow vertically to about three feet, giving it a bush appearance.

Another key characteristic for identification are the lavender flowers it produces, few other plants in our dunes do – so this is a good thing to look for. The flowers appear in late spring and summer. They are actually quite pretty. In the fall, the flowers are replaced by numerous large seeds, which form in clusters where the flowers were. These seeds are problematic in that they can remain viable for up to six months if they fall into the water – increasing their chance for dispersal.

So what is the problem?

In the Carolina’s this species was planted intentionally. They quickly learned of its aggressive nature and have had a state task force to battle it. The plant is allopathic – it can release toxins that kill neighboring plants allowing them to move into that space – this includes sea oats. Beach vitex has a taproot system, unlike the fibrous one of the sea oat, and cannot stabilize a dune as well – which is a problem during storms. In the Carolina’s there are numerous beach fronts where this is the only plant growing, a problem waiting to happen. Though there are no reports of it happening, it also has the potential to affect sea turtle nesting.

Beach Vitex Blossom. Photo credit: Rick O’Connor

So what do I do if I see it?

Contact us… You can contact me at roc1@ufl.edu, or call (850) 475-5230. Try to give us the best description of where the location is as you can. Many phones now come with an app that has a compass. This app also gives you your latitude and longitude. If your phone does not have this, again, give us the best description of the location you can. If you can include a photograph, that would be great. There are numerous other invasive species roaming our area, and you are welcome to report any you find to us. We hope to stay on top of these early arrivals and keep them under control.

by Rick O'Connor | Jul 6, 2018

Shrimp, oysters, blue crab and fish have been harvested from the Pensacola Bay System (PBS) for decades, although there has been a decline in all in recent years. Annual landings (in pounds) have ranged from

- Fish 66,000 – 4,600,000 (most are scaienids)

- Brown shrimp 43,000 – 906,000

- Oysters 0 – 492,000

- Blue crab 400 – 137,000

There is a concern about the safety of seafood harvested from our estuary… sort of. Many local residents and visitors ask frequently about the safety of these products. However, when programs are held to provide this information they are not well attended, and when articles are posted – few view them. I think there is a concern for the safety of seafood products, particularly those from our estuaries – so I cannot explain the lack of interest in the presentations and articles.

Commercial seafood in Pensacola has a long history.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

One contaminant that gets a lot of press is mercury. The toxic form of mercury is methylmercury. This form of mercury impairs brain development of fetuses – hearing, vision, and muscle function in adults. Studies suggests that the primary source of mercury in the waters of the PBS is the atmosphere. Advisories have been issued for Escambia, Blackwater, and Yellow Rivers. There have also been advisories for local largemouth and king mackerel. This is one of the metals whose concentrations within the PBS is higher than neighboring estuaries – especially in our bayous (see https://blogs.ifas.ufl.edu/escambiaco/2018/06/13/restoring-the-health-of-pensacola-bay-what-can-you-do-to-help-bioaccumulation-of-toxins/.) Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP) has issued Total Maximum Daily Loads (TDMLs) for mercury in the PBS.

So How Much is Too Much?

For monitoring purposes, total mercury (THg) is easier and less expensive to than the toxic form methylmercury (MHg). Many believe the amount of THg is equivalent to the concentration of MHg, and so it is used as a proxy for MHg.

Both the U.S. EPA and the FDEP recommend concentrations of THg not be higher than 0.3 ppm, and 0.1 ppm for pregnant women (or women planning a pregnancy).

Fish

Since 2000, four studies have been conducted on six species of fish in the PBS. Concentrations of THg ranged from 0.02 – 0.88 ppm and averaged between 0.2 – 0.4 ppm.

Blue Crab

Two studies have been conducted since 2007 found mercury concentrations ranged from 0.07 – 1.1 ppm.

Oysters

30 years ago, studies were finding concentrations of THg in oysters around 0.02 ppm. Repeated studies between 1986 and 1996 found an increase to 0.3 ppm.

Overall

Studies suggest that shrimp and oysters have lower concentrations of THg than blue crab and fish.

Seafood has a long history along Florida’s panhandle.

Photo: Betsy Walker

How often have samples exceeded the safe levels suggested by EPA, FDEP, and FDA?

| Group |

Recommended highest level |

% of times samples from PBS exceeded this limit |

| Subsistence Fishermen |

0.049 ppm |

50-90%

(89% for blue crab and oysters) |

| Pregnant females |

0.1 ppm |

50-90%

(88% for blue crab) |

| General public |

0.3 ppm |

5-20%

(12% for blue crabs)

(27% for fish) |

| Food and Drug Administration recommendation |

1.0 ppm |

0% |

The concern for mercury in local seafood has led to a reduction of consuming all seafood by pregnant women – period. Recent studies have shown this can have negative effects on the developing baby as well. The recommendation is to avoid fish that have been tested high in THg. Most of these are high on the food chain – such as king mackerel, shark, and swordfish. You can find the latest on seafood safety and advisories at https://myescambia.com/our-services/natural-resources-management/marine-resources/seafood-safety. Another piece of this story is the belief, by many, that selenium can lower the toxicity of MHg. Many believe that molar ratios of selenium and mercury greater than 1.0 can reduce the toxicity. However, there have been no studies on molar ratios of these elements in the PBS.

The bottom line on this issue is to be selective on the seafood products you consume.

The most popular seafood species – shrimp.

Reference

Lewis, M.J., J.T. Kirschenfeld, T. Goodhart. 2016. Environmental Quality of the Pensacola Bay System: Retrospective Review for Future Resource Management and Rehabilitation. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Gulf Breeze FL. EPA/600/R-16/169.