by Sheila Dunning | Oct 4, 2024

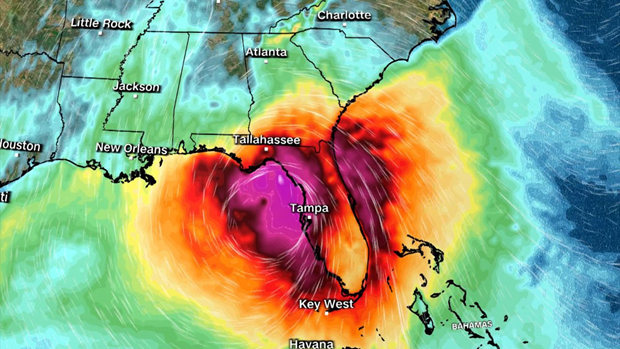

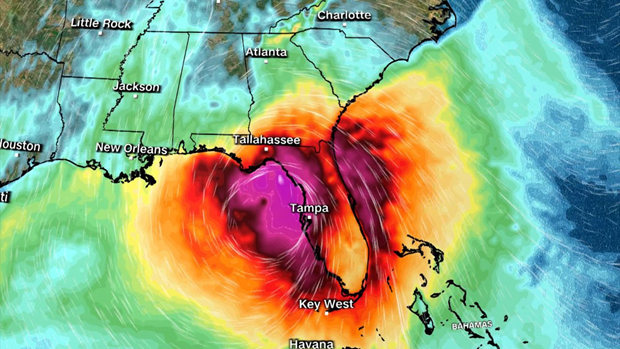

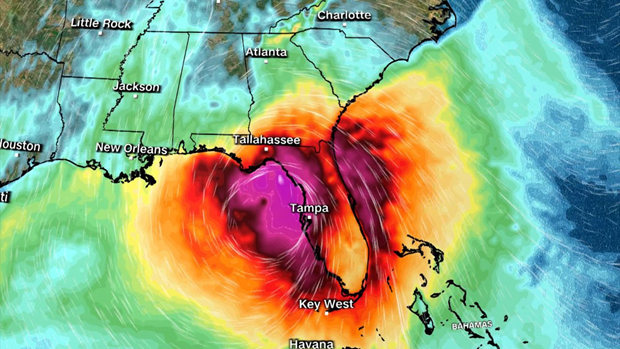

Coastal wetlands are some of the most ecologically productive environments on Earth. They support diverse plant and animal species, provide essential ecosystem services such as stormwater filtration, and act as buffers against storms. As Helene showed the Big Bend area, storm surge is devastating to these delicate ecosystems.

Hurricane Track on Wednesday evening.

As the force of rushing water erodes soil, uproots vegetation, and reshapes the landscape, critical habitats for wildlife, in and out of the water, is lost, sometimes, forever. Saltwater is forced into the freshwater wetlands. Many plants and aquatic animal species are not adapted to high salinity, and will die off. The ecosystem’s species composition can completely change in just a few short hours.

Prolonged storm surge can overwhelm even the very salt tolerant species. While wetlands are naturally adept at absorbing excess water, the salinity concentration change can lead to complete changes in soil chemistry, sediment build-up, and water oxygen levels. The biodiversity of plant and animal species will change in favor of marine species, versus freshwater species.

Coastal communities impacted by a hurricane change the view of the landscape for months, or even, years. Construction can replace many of the structures lost. Rebuilding wetlands can take hundreds of years. In the meantime, these developments remain even more vulnerable to the effects of the next storm. Apalachicola and Cedar Key are examples of the impacts of storm surge on coastal wetlands. Helene will do even more damage.

Many of the coastal cities in the Big Bend have been implementing mitigation strategies to reduce the damage. Extension agents throughout the area have utilized integrated approaches that combine natural and engineered solutions. Green Stormwater Infrastructure techniques and Living Shorelines are just two approaches being taken.

So, as we all wish them a speedy recovery, take some time to educate yourself on what could be done in all of our Panhandle coastal communities to protect our fragile wetland ecosystems. For more information go to:

https://ffl.ifas.ufl.edu/media/fflifasufledu/docs/gsi-documents/GSI-Maintenance-Manual.pdf

https://blogs.ifas.ufl.edu/news/2023/11/29/cedar-key-living-shorelines/

by Scott Jackson | Apr 17, 2020

Florida Sea Grant is maintaining a curated list of disaster assistance options for Florida’s coastal businesses disrupted by COVID-19.

Boats at calmly at rest in Massalina Bayou, Bay County, Florida.

The list contains links to details about well- and lesser-known options and includes “quick takeaway” overviews of each assistance program. Well-funded and widely available programs are prioritized on the list. The page also houses a collection of links to additional useful resources, including materials in Spanish.

“There is a lot of information floating around out there,” says Andrew Ropicki, Florida Sea Grant natural resources economist and one of the project leaders. “We are trying to provide a timely and accurate collection of resources that will be useful for Florida coastal businesses.”

Ropicki and others on the project team stress that the best place to start an application for disaster aid is to visit with your bank or lender and the Florida Small Business Development Center (SBDC). They also suggest contacting local representatives by telephone or email and not to just rely on internet-based applications.

Overview of Selected Disaster Assistance Programs Benefiting Florida Small Businesses including Agriculture, Aquaculture, and Fisheries (COVID-19)

The project team — which includes experts from Florida Sea Grant, University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (UF/IFAS) Extension, and the UF/IFAS Center for Public Issues Education — reviews the page regularly for accuracy and to include new options.

Commercial seafood is a large part of Florida’s economy and culture.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

“[I] really appreciate the outstanding work that you and FSG have done on consolidating the various types of aid available to fishermen due to the virus,” said Bill Kelly, executive director of the Florida Keys Commercial Fishermen’s Association, in a recent email. “I’ve been searching for a comprehensive listing and you just provided it.”

by Will Sheftall | Jul 22, 2016

Birds, migration, and climate change. Mix them all together and intuitively, we can imagine an ecological train wreck in the making. Many migratory bird species have seen their numbers plummet over the past half-century – due not to climate change, but to habitat loss in the places they frequent as part of their jet-setting life history.

Migrating songbirds forage for insects in coastal scrub-shrub habitat. Photo credit: Erik Lovestrand, UF IFAS Extension

Now come climate simulation models forecasting more change to come. It will impact the strands of places migrants use as critical habitat. Critical because severe alteration of even one place in a strand can doom a migratory species to failure at completing its life cycle. So what aspect of climate change is now threatening these places, on top of habitat alteration by humans?

It’s the change in weather patterns and sea level that we’re already beginning to see, as the impacts of global warming on Earth’s ocean-atmosphere linkage shift our planetary climate system into higher gear.

For migratory birds, the journey itself is the most perilous link in the life history chain. A migratory songbird is up to 15 times more likely to die in migration than on its wintering or breeding grounds. Headwinds and storms can deplete its energy reserves. Stopover sites for resting and feeding are critical. And here’s where the Big Bend region of Florida figures prominently in the life history of many migratory birds.

According to a study published in March of this year (Lester et al., 2016), field research on St. George Island documented 57 transient species foraging there as they were migrating through in the spring. That number compares favorably with the number of species known to use similar habitat at stopover sites in Mississippi (East Ship Island, Horn Island) as well as other central and western Gulf Coast sites in Alabama, Louisiana, and Texas.

We now can point to published empirical evidence that the eastern Gulf Coast migratory route is used by as many species as other Gulf routes to our west. This confirmation makes conservation of our Big Bend stopover habitat all the more relevant.

The authors of the study observed 711 birds using high-canopy forest and scrub/shrub habitat on St. George Island. Birds were seeking energy replenishment from protein-rich insects, which were reported to be more abundant in those habitats than on primary dunes, or in freshwater marshes and meadows.

So now we know that specific places on our barrier islands that still harbor forests and scrub/shrub habitat are crucial. On privately-owned island property, prime foraging habitat may have been reduced to low-elevation mixed forest that is often too low and wet to be turned into dense clusters of beach houses.

Coastal slash pine forest is vulnerable to sea level rise. Photo credit: Erik Lovestrand, UF IFAS Extension

Think tall slash pines and mid-story oaks slightly ‘upslope’ of marsh and transitional meadow, but ‘downslope’ of the dune scrub that is often cleared for development.

“OK, I get it,” you say. “It’s as if restaurant seating has been reduced and the kitchen staff laid off. Somebody’s not going to get served.” Destruction of forested habitat on our Gulf Coast islands has significantly reduced the amount of critical stopover habitat for birds weary from flying up to 620 miles across the Gulf of Mexico since their last bite to eat.

But why the concern with climate change on top of this familiar story of coastal habitat lost to development? After all, we have conservation lands with natural habitat on St. Vincent, Little St. George, the east end of St. George, and parts of Dog Island and Alligator Point. Shouldn’t these islands be able to withstand the impacts of stronger and/or more frequent coastal storms, and higher seas – and their forested habitat still serve the stopover needs of migratory birds?

Let’s revisit the “low and wet” part of the equation. Coastal forested habitat that’s low and wet – either protected by conservation or too wet to be developed – is in the bull’s eye of sea level rise (SLR), and sooner rather than later.

Using what Lester et al. chose as a reasonably probable scenario within the range of SLR projections for this century – 32 inches, these low-elevation forests and associated freshwater marshes would shrink in extent by 45% before 2100. It could be less; it could be more. Conditions projected for a future date are usually expressed as probable ranges. Experience has proven them too conservative in some cases.

The year 2100 seems far away…but that’s when our kids or grandkids can hope to be enjoying retirement at the beach house we left them. Hmm.

Scientists CAN project with certainty that by the time SLR reaches two meters (six and a half feet) – in whatever future year that occurs, 98% of “low and wet” forested habitat will have transitioned to marsh, and then eroded to tidal flat.

But before we spool out the coming years to a future reality of SLR that has radically changed the coastline we knew, let’s consider where the crucial forested habitat might remain on the barrier islands of the next generation’s retirement years:

It could remain in the higher-elevation yard of your beach house, perhaps, if you saved what remnant of native habitat you could when building it. Or if you landscaped with native trees and shrubs, to restore a patch of natural habitat in your beach house yard.

Migratory songbird stopover habitat saved during beach house construction. Photo credit: Erik Lovestrand, UF IFAS Extension

We’ve all thought that doing these things must be important, but only now is it becoming clear just how important. Who would have thought, “My beach house yard: the island’s last foraging refuge for migratory songbirds!” even in our most apocalyptic imagination?

But what about coastal mainland habitat?

The authors of the March 2016 St. George Island study conclude that, “…adjacent inland forested habitats must be protected from development to increase the probability that forested stopover habitat will be available for migrants despite SLR.” Jim Cox with Tall Timbers Research Station says that, “birds stop at the first point of land they find under unfavorable weather conditions, but also continue to migrate inland when conditions are favorable.”

Migratory birds are fortunate that the St. Marks Refuge protects inland forested habitat just beyond coastal marshland. A longer flight will take them to the leading edge of salty tidal reach. There the beautifully sinuous forest edge lies up against the marsh. This edge – this trailing edge of inland forest – will succumb to tomorrow’s rising seas, however.

Sea level rise will convert coastal slash pine forest to salt marsh. Photo credit: Erik Lovestrand, UF IFAS Extension

As the salt boundary moves relentlessly inland, it will run through the Refuge’s coastal buffer of public lands, and eventually knock on the surveyor’s boundary with private lands. All the while adding flight miles to the migration journey.

In today’s climate, migrants exhausted from bucking adverse weather conditions over the Gulf may not have enough energy to fly farther inland in search of forested foraging habitat. Will tomorrow’s climate make adverse Gulf weather more prevalent, and migration more arduous?

Spring migration weather over the Gulf can be expected to change as ocean waters warm and more water vapor is held in a warmer atmosphere. But HOW it will change is difficult to model. Any specific, predictable change to the variability of weather patterns during spring migration is therefore much less certain than SLR.

What will await exhausted and hungry migrants in future decades? Our community decisions about land use should consider this question. Likewise, our personal decisions about private land management – including beach house landscaping. And it’s not too early to begin.

Erik Lovestrand, Sea Grant Agent and County Extension Director in Franklin County, co-authored this article.

by Laura Tiu | Apr 22, 2016

The Deepwater Horizon (DWH) oil spill occurred about 50 miles offshore of Louisiana in April 2010. Approximately 172 million gallons of oil entered the Gulf of Mexico. Five years after the incident, locals and tourists still have questions. This article addresses the five most common questions.

QUESTION #1: Is Gulf seafood safe to eat?

Ongoing monitoring has shown that Gulf seafood harvested from waters that are open to fishing is safe to eat. Over 22,000 seafood samples have been tested and not a single sample came back with levels above the level of concern. Testing continues today.

QUESTION #2: What are the impacts to wildlife?

This question is difficult to answer as the Gulf of Mexico is a complex ecosystem with many different species — from bacteria, fish, oysters, to whales, turtles, and birds. While oil affected individuals of some fish in the lab, scientists have not found that the spill impacted whole fish populations or communities in the wild. Some fish species populations declined, but eventually rebounded. The oil spill did affect at least one non-fish population, resulting in a mass die-off of bottlenose dolphins. Scientists continue to study fish populations to determine the long term impact of the spill.

Question #3: What cleanup techniques were used, and how were they implemented?

Several different methods were used to remove the oil. Offshore, oil was removed using skimmers, devices used for removing oil from the sea’s surface before it reaches the coastline. Controlled burns were also used, where surface oil was removed by surrounding it with fireproof booms and burning it. Chemical dispersants were used to break up the oil at the surface and below the surface. Shoreline cleanup on beaches involved sifting sand and removing tarballs and mats by hand.

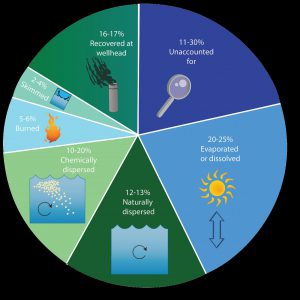

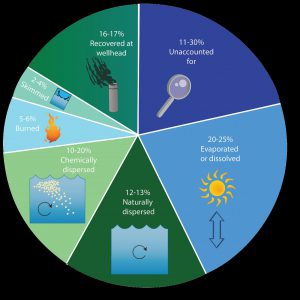

QUESTION #4: Where did the oil go and where is it now?

The oil spill covered 29,000 square miles, approximately 4.7% of the Gulf of Mexico’s surface. During and after the spill, oil mixed with Gulf of Mexico waters and made its way into some coastal and deep-sea sediments. Oil moved with the ocean currents along the coast of Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida. Recent studies show that about 3-5% of the unaccounted oil has made its way onto the seafloor.

QUESTION #5: Do dispersants make it unsafe to swim in the water?

The dispersant used on the spill was a product called Corexit, with doctyl sodium sulfosuccinate (DOSS) as a primary ingredient. Corexit is a concern as exposure to high levels can cause respiratory problems and skin irritation. To evaluate the risk, scientists collected water from more than 26 sites. The highest level of DOSS detected was 425 times lower than the levels of DOSS known to cause harm to humans.

For additional information and publications related to the oil spill please visit: https://gulfseagrant.wordpress.com/oilspilloutreach/

Adapted From:

Maung-Douglass, E., Wilson, M., Graham, L., Hale, C., Sempier, S., and Swann, L. (2015). Oil Spill Science: Top 5 Frequently Asked Questions about the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. GOMSG-G-15-002.

An estimate of what happened to approximately 200 million gallons oil from the DWH oil spill. Data from Lehr, 2014. (Florida Sea Grant/Anna Hinkeldey)

The Foundation for the Gator Nation, An Equal Opportunity Institution.

by Libbie Johnson | Feb 24, 2016

Libbie Johnson

Libbie Johnson

UF IFAS Escambia County Extension

Northwest Florida can be a pond owner’s paradise. There is usually enough rainfall to keep ponds filled, catfish, bass, and brim are well adapted to the environmental conditions, and there is a long season to catch fish.

One of the biggest problems pond owners face is the constant struggle with pond vegetation. Some pond vegetation is good. It provides a cover for young fish, helps stabilize the shoreline or bank, and some vegetative species are attractive wildlife.

However some species are highly invasive and can completely overtake a pond. One such species is water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes).

The water hyacinth is a floating plant, which if left unchecked and allowed to grow to its maximum potential, can weigh up to 200 tons per acre of water. In rivers, it can choke out other vegetation and make navigation difficult to impossible.

Water hyacinth, as an ornamental plant, is a wolf in sheep’s clothing. The plants intertwined and form huge floating mats which can root on muddy surfaces, as seen in the photo below.

The plant will be several inches tall, has showy lavender flowers, with rounded, shiny, smooth leaves. These leaves are attached to spongy stalks that help keep the plants afloat. The prolific roots are dark and feathery.

In Northwest Florida this pest commonly dies back in the winter. Unfortunately it is able to regrow when the weather and water warm.

Water hyacinth is not a native species. It is believed to have been introduced into the U.S. in 1884 at an exposition in New Orleans. Within 70 years of reaching Florida, the plant covered 126,000 acres of waterways (Schmitz et al. 1993).

Water hyacinth is on the FL DACS Prohibited Aquatic Plant List – 5B-64.011. According to Florida Statute 369.25, “No person shall import, transport, cultivate, collect, sell, or possess any noxious aquatic plant listed on the prohibited aquatic plant list established by the department without a permit issued by the department.”

To control a small infestation, the plants can be gathered from the surface, brought to the shore, left to dry and then disposed of in the garbage. There are biological control options—water hyacinth weevils will be useful in keeping the plant populations down.

The spongy petiole helps keeps the plant afloat.

Finally, chemical herbicide options may be the best alternative. University of Florida Aquatic Vegetation Specialist, Dr. Langeland, wrote Efficacy of Herbicide Active Ingredients Against Aquatic Weeds, a good publication that will help you to determine which herbicide will work best for different weeds.

NOTE: The middle of the summer is generally not the ideal time for applying herbicide on pond vegetation. For more information on weed control in Florida ponds, please see Weed Control in Florida Ponds. If you have any questions about identifying a pond weed, contact your local county Extension agent.

by Rick O'Connor | Sep 25, 2015

In the last edition in this series we discussed some of the issues and problems our estuaries are facing. For the final edition for National Estuaries Week we want to leave you with some ideas on you can help improve things.

The first issue we dealt with was eutrophication – or nutrient overloading. The primary nutrient we have issues with in this part of the panhandle is nitrogen. Nitrates can converted from other forms of nitrogen and can be discharged directly into the water. Common sources are leaf litter, animal waste, commercial fertilizers, and human sewage. Most of this is discharged into our waters via stormwater runoff. This runoff occurs from our properties (due to the lack of natural vegetation holding it) and from stormwater drains (where it is directed through our engineering projects).

One method of dealing with this problem is restoring the shoreline back to its natural state. This is called Living Shorelines and they are being restored all over the country. In most cases locally Living Shorelines would be restoring salt marshes to our shorelines. There are some issues with this. It lessens the amount of open beach you have to enjoy. You have to purchase special plants to do this, and it may require a permit from the state of Florida. Permits are required only if you are planting at or below the mean high tide line; all submerged lands are actually the property of the state of Florida. Permits for Living Shorelines can be obtained from the Florida Department of Environmental Protection.

FDEP planting a living shoreline on Bayou Texar in Pensacola.

Photo: FDEP

The first question you would want to ask when considering a Living Shoreline for your property is whether there was a salt marsh along your shore historically. Salt marshes require low energy beaches to establish themselves and your location may not be such. If you are not sure you can contact the Sea Grant Agent in your county to provide assistance with that determination. If you feel your property would support a Living Shoreline then you will need a permit. There is the “long form” and the “short form” permit. The “short form” obviously what you want and it costs less also. However certain criteria must be met in order to be exempt from the “long form”. To determine whether you are exempt from the “long form” visit https://www.flrules.org/gateway/RuleNo.asp?title=ENVIRONMENTAL%20RESOURCE%20PERMITTING&ID=62-330.051 Click “view rule” and scroll down to (12)(e). If you feel that you qualify for the exemption then it is as simple as completing the form and submitting your check. You should have your permit in just a few weeks. If you do not qualify then it is recommended that you contact the Florida Department of Environmental Protection for advice on moving forward. (850) 595-8300.

Whether you qualify for a Living Shoreline or not – or even if you do not live on the water – there is a landscaping program that you can adopt that will help a lot. It is called Florida Friendly Landscaping. This UF/IFAS program helps homeowners select the “right plant for the right place”. Basically the idea is to landscape your yard with native plants that require little or no fertilizing or water. Not only does this program help our estuaries it saves the homeowner money. One of the first things you will want to do when planning a Florida Friendly Landscape is have your soil tested. The county extension office provides this service for about $7. If interested contact your county extension office about where to pick up the soil testing sample bags. Rain barrels and rain gardens are also good ways to reduce water runoff and save water for those times when you might need it. A trickle hose connected to a rain barrel can reduce runoff and your water bill.

Florida Friendly Landscaping involves using native plants that require less water and fertilizer.

Photo: Southwest Florida Water Management District

We are not certain how much of the animal waste is in fact human but we do know that much of the human waste is from septic tanks. If you have a septic tank – maintain it. Most of the problems come from those that are not maintained well. If you can connect to a sewer line we recommend you do this. The sewer is not without its problems but the problems are much reduced. If you own a pet – clean up behind them.

The leaf litter problem is just that… a problem. Within the city limits many municipalities will collect your yard waste. In Pensacola they do so using a large “claw” however this claw leaves large holes in your yard – so people place the yard waste in the street. Doing this encourages runoff into the bay and the problems we have already discussed. So many will bag it. In Escambia County the yard waste is converted into mulch and is free to the public. However if the yard waste is placed in plastic bags they cannot do this. It’s tough problem. One answer is to develop your own compost pile and dispose of your yard waste there. Your county extension office can help you with different methods of composting and help you select the method that is best for you.

A commercial composting bend that can purchased at many locations or on line.

Photo: UF/IFAS

Composting bends can also be made from recycle materials such as pallets.

Photo: UF/IFAS

All of these suggestions about can reduce nutrients and bacteria in our waterways that contribute to fish kills and health advisories. It will reduce turbidity, which will help seagrasses, and actually Living Shorelines can reduce shoreline erosion.

These same practices can not only improve water quality they could help restore some of our declining fisheries. Living Shorelines provide needed habitat for many commercial and recreational valuable species. As mentioned, these projects will remove much of the sediment improving water clarity to a point where seagrasses can restore themselves and who knows… maybe the scallop will return. On the subject of scallops, Florida Sea Grant conducts scallops surveys in some of panhandle estuaries in the summer. You can volunteer to be a scallop surveyor and assist with data collection that could support a scallop restoration projects. When fishing follow the regulations. They may seem unfair and out dated but know that fisheries managers are trying to get it right and your cooperation will certainly help develop a sustainable fishery for years to come.

The issue of garbage is another tough one. We have been conducting educational programs for decades trying to reduce the amount of solid waste – it’s still there. Many of the local residents are pretty good at taking their trash with them and recycling monofilament fishing line… but not all. Encourage your friends to “take it with them” and “leave no trace” when they go home each day. Out of town visitors can be a problem. Local education from all of us should help some. Participate in one of the CleanPeace’s Ocean Hours. If in the Santa Rosa and Escambia area contact the Sea Grant Agents from those counties for more information. If from another county, contact your local county extension office for information on beach clean ups.

A sea turtle entangled in a discarded fishing net.

Photo: NOAA

Our estuaries have improved significantly from where they were in the late ‘60’s and early 70’s. A little on our part now we can improve them even more. We hope you have learned something new about your local estuary during National Estuaries Week. We hope you will take the time to enjoy these great bodies of water and do what you can to protect for future years.