by Jennifer Bearden | Jan 31, 2025

Before you know it spring turkey season will be upon us and now is the time to start planning a killer turkey food plot. Establishing a great food plot takes more than just planting seeds. It takes planning and preparation prior to planting those seeds. The prime turkey food plot is chufas. Chufas are yellow nutsedges that turkeys absolutely love.

The first step is finding a good spot. A 20ft x 20ft spot with no trees and ample sunlight will work well. You can select a larger spot but that increases the cost of planting. Chufas prefer full sunlight so make sure the area gets 6-8 hours of sunlight per day.

Next step is to take a soil sample from the area. Here’s a video demonstrating how to properly take a soil sample. When you get your soil sample results back, you will want to adjust the pH as necessary. Perform this task well ahead of planting to give the lime time to raise the pH. Chufas grow best with the soil pH between 6.0-7.0.

Now other animals love chufas too, like hogs and rabbits. I wouldn’t plant chufas if you know you have a large population of rabbits or you have a feral hog problem. Reduce those populations before planting chufas.

Other options include plants such as brown top millet and buckwheat. Turkeys love tender young shoots. You can plant these in March ahead of spring turkey season. These plots also will attract insects which the turkeys feed on.

Now we get to the fun part – planting. Chufas can be planted anytime between April and July. They germinate quickly once soil temperatures are above 65º F.. You can plow the area or use a herbicide like glyphosate to kill existing vegetation. For chufas, you can use a pre-emergent herbicide like trifluralin or pendimethalin to help suppress weeds during the growing season.

| Plant |

Broadcast Seeding Rate |

| Chufas |

40-50lb/acre |

| Brown top millet |

20-25lb/acre |

| Buckwheat |

50- 55lb/acre |

I find that packing the soil after broadcasting the seed, either by driving over it or by using a cultipacker, helps with germination as the seeds flourish with a firm seed bed.

Next, fertilize according to your soil test results and enjoy a great spring turkey season.

by Ray Bodrey | Nov 21, 2024

Recently Jennifer Bearden, our Agriculture & Natural Resource Agent in Okaloosa County wrote a great article on “Common Wildlife Food Plot Mistakes”. The following information is a mere supplement in establishing food plots. Planting wildlife forages has become a great interest in the Panhandle. North Florida does have its challenges with sandy soils and seasonal patterns of lengthy drought and heavy rainfall. With that said, varieties developed and adapted for our growing conditions are recommended. Forage blends are greatly suggested to increase longevity and sustainability of crops that will provide nutrition for many different species.

Hairy Vetch – Ray Bodrey

In order to be successful and have productive wildlife plots. It is recommended that you have your plot’s soil tested and apply fertilizer and lime according to soil test recommendations. Being six weeks from optimal planting, there’s no time like the present.

Below are some suggested cool season wildlife forage crops from UF/IFAS Extension. Please see the UF/IFAS EDIS publication, “A Walk on the Wild Side: 2024 Cool-Season Forage Recommendations for Wildlife Food Plots in North Florida” for specific varieties, blends and planting information. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/AG/AG13900.pdf

Winter legumes are more productive and dependable in the heavier clay soils of northwest Florida or in sandy soils that are underlain by a clay layer than in deep upland sands or sandy flatwoods. Over seeded white clover and ryegrass can grow successfully on certain flatwoods areas in northeast Florida. Alfalfa, clovers, vetch and winter pea are options of winter legumes.

Cool-season grasses generally include ryegrass and the small grains: wheat, oats, rye, and triticale (a human-made cross of wheat and rye). These grasses provide excellent winter forage and a spring seed crop which wildlife readily utilize

Brassica and forage chicory are annual crops that are highly productive and digestible and can provide forage as quickly as 40 days after seeding, depending on the species. Forage brassica crops such as turnip, swede, rape, kale and radish can be both fall- and spring-seeded. Little is known about the adaptability of forage brassicas to Florida or their acceptability as a food source for wildlife.

Deer taking advantage of a well maintained food plot. Photo: Mark Mauldin

For more information, contact your local county extension office.

UF/IFAS Extension is an Equal Opportunity Institution.

by Thomas Derbes II | Nov 8, 2024

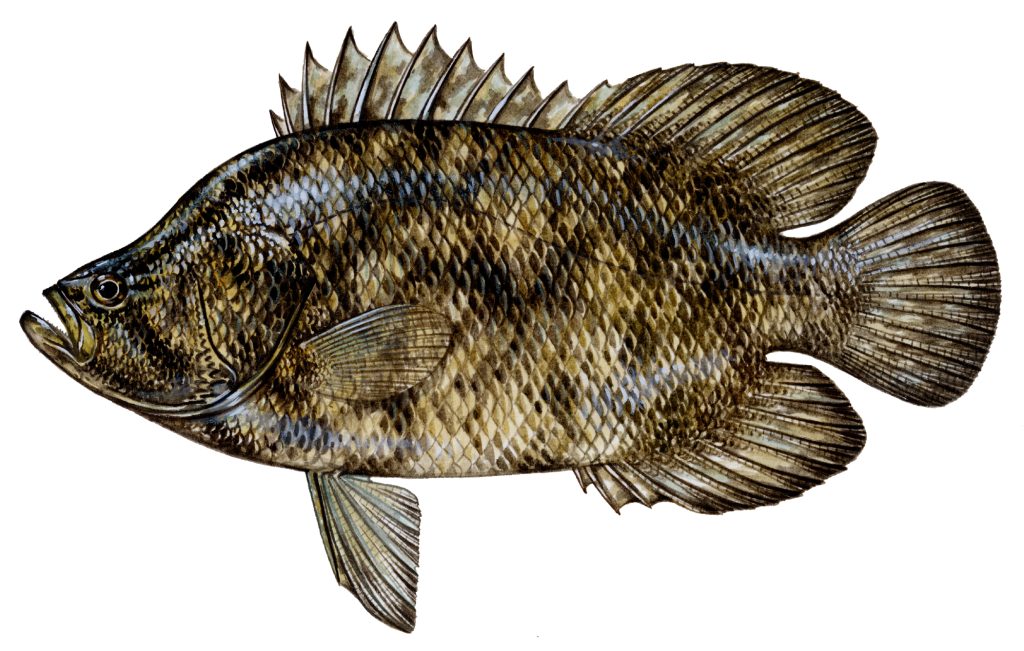

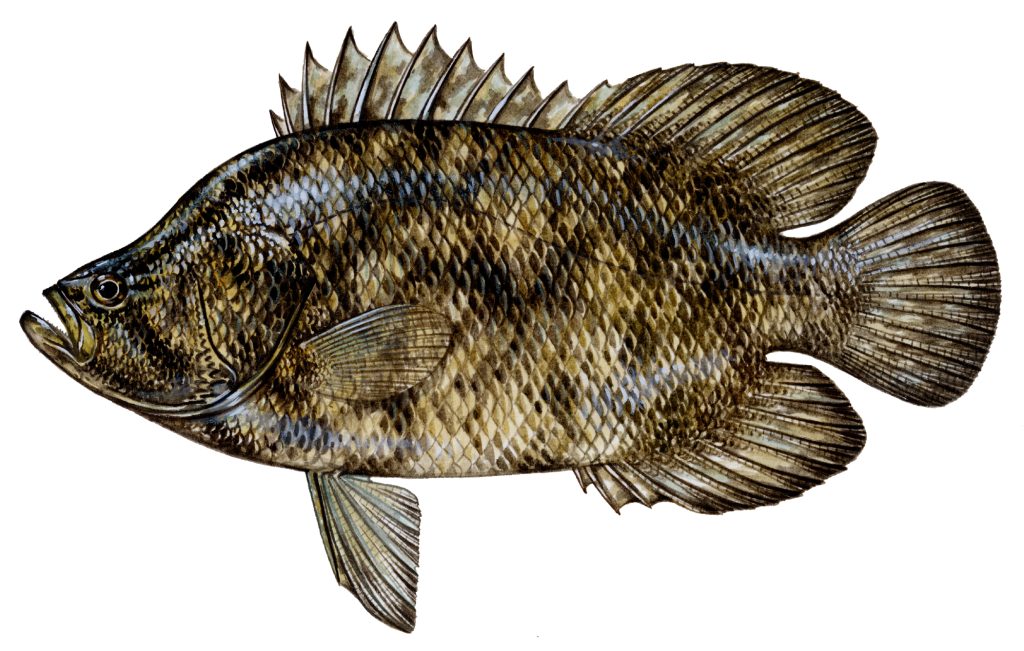

The Atlantic Tripletail (Lobotes surinamensis) is a very prized sportfish along the Florida Panhandle. Typically caught as a “bonus” fish found along floating debris, the tripletail is a hard fighting fish and excellent table fare. Just as the name implies, this fish is equipped with three “tails” that help aid it in propulsion; and also help contribute to their strong fighting spirit. In addition to the caudal fin, tripletail have very pronounced “lobed” dorsal and anal fin soft rays that sit very far back on the body, giving it the appearance of three tails (triple-tails).

Atlantic Tripletail (Lobotes surinamensis) – FWC, Diane Rome Peebles 1992

Tripletail are found in tropical and subtropical seas around the world (except the eastern Pacific Ocean) and are the only member of their family found in the Gulf of Mexico. Tripletail can be found in all saltwater environments, from the upper bays to the middle of the Gulf of Mexico. In the Florida Panhandle, tripletail begin to show up in the bays beginning in May and can be found up until October/November. They are masters of disguise, usually found floating along floating debris, crab trap buoys, navigation pilings, and floating algae like Sargassum. When tripletail are young, they are able to change their colors to match the debris, albeit it is usually a variation of yellow, brown, and black. Adult tripletail can change color as well, but the coloration is not as vibrant as the juveniles. Floating alongside debris and other floating materials protects them from predators and gives them food access. Small crustaceans, like shrimp and crabs, and small fish will gather along the floating debris, looking for protection, giving the camouflaged tripletail an easy meal.

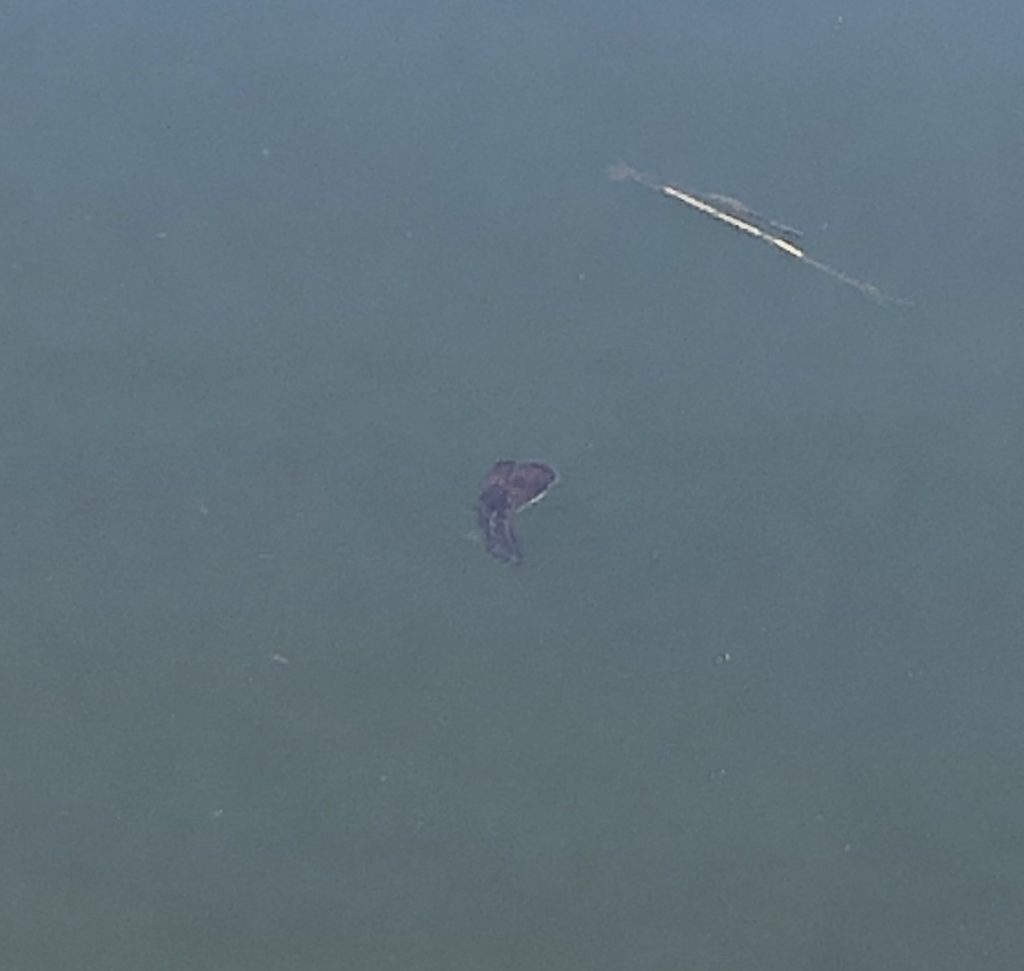

Baby Tripletail or Leaf? – Thomas Derbes II

Tripletail are opportunistic feeders that are what I classify as “lazy hunters.” Tripletail will hang out along any floating debris and wait for the food to come to them. They typically will not chase their prey items too far and will abandon the hunt if they expend too much energy. Since they are opportunistic feeders, their diet varies widely, but they cannot resist a baby blue crab, shrimp, or small baitfish like menhaden (Brevoortia patronus) that might visit their floating oasis. When further offshore, it is not uncommon to find many tripletail “laying out” on sargassum or floating debris. I personally have seen a dozen full-sized tripletail inside of a large traffic barrel 25 miles offshore that saved a skunk of a deep-dropping fishing trip.

Tripletail Caught Off An Oyster Farm – Brandon Smith

When targeting tripletail, anglers will typically sit at the highest point of the boat (some anglers have towers for spotting tripletail) and cruise along floating crab trap buoys, pilings, and sometimes oyster farms looking for Tripletail. These fish are very easily spooked, and a slow, quiet approach is best. Once in casting distance, toss your preferred bait (I typically want to have baby crabs or live shrimp when targeting tripletail) close to the floating structure, but not too close to spook the fish. You can usually watch the fish eat your bait (another added bonus) and once you set the hook, the fight is on! In the state of Florida, tripletail must be a minimum of 18 inches and there is a daily bag limit of 2 fish per person. Be very careful handling tripletail as they have very sharp dorsal and anal fins and their operculum (gill cover) is also very sharp with hidden spines.

So next time you’re out fishing and see something floating, make sure you give it a good look over. There might be a camouflaged tripletail that you can add to your fish box!

Tripletail Caught While Working Oyster Gear – Thomas Derbes

by Sheila Dunning | Oct 4, 2024

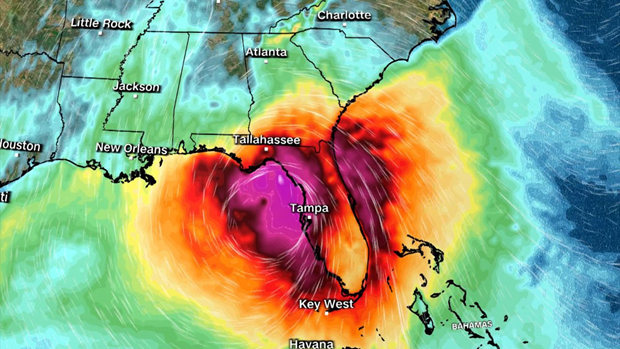

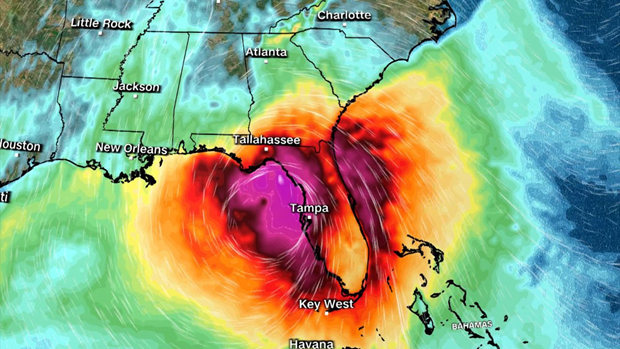

Coastal wetlands are some of the most ecologically productive environments on Earth. They support diverse plant and animal species, provide essential ecosystem services such as stormwater filtration, and act as buffers against storms. As Helene showed the Big Bend area, storm surge is devastating to these delicate ecosystems.

Hurricane Track on Wednesday evening.

As the force of rushing water erodes soil, uproots vegetation, and reshapes the landscape, critical habitats for wildlife, in and out of the water, is lost, sometimes, forever. Saltwater is forced into the freshwater wetlands. Many plants and aquatic animal species are not adapted to high salinity, and will die off. The ecosystem’s species composition can completely change in just a few short hours.

Prolonged storm surge can overwhelm even the very salt tolerant species. While wetlands are naturally adept at absorbing excess water, the salinity concentration change can lead to complete changes in soil chemistry, sediment build-up, and water oxygen levels. The biodiversity of plant and animal species will change in favor of marine species, versus freshwater species.

Coastal communities impacted by a hurricane change the view of the landscape for months, or even, years. Construction can replace many of the structures lost. Rebuilding wetlands can take hundreds of years. In the meantime, these developments remain even more vulnerable to the effects of the next storm. Apalachicola and Cedar Key are examples of the impacts of storm surge on coastal wetlands. Helene will do even more damage.

Many of the coastal cities in the Big Bend have been implementing mitigation strategies to reduce the damage. Extension agents throughout the area have utilized integrated approaches that combine natural and engineered solutions. Green Stormwater Infrastructure techniques and Living Shorelines are just two approaches being taken.

So, as we all wish them a speedy recovery, take some time to educate yourself on what could be done in all of our Panhandle coastal communities to protect our fragile wetland ecosystems. For more information go to:

https://ffl.ifas.ufl.edu/media/fflifasufledu/docs/gsi-documents/GSI-Maintenance-Manual.pdf

https://blogs.ifas.ufl.edu/news/2023/11/29/cedar-key-living-shorelines/

by Thomas Derbes II | Aug 23, 2024

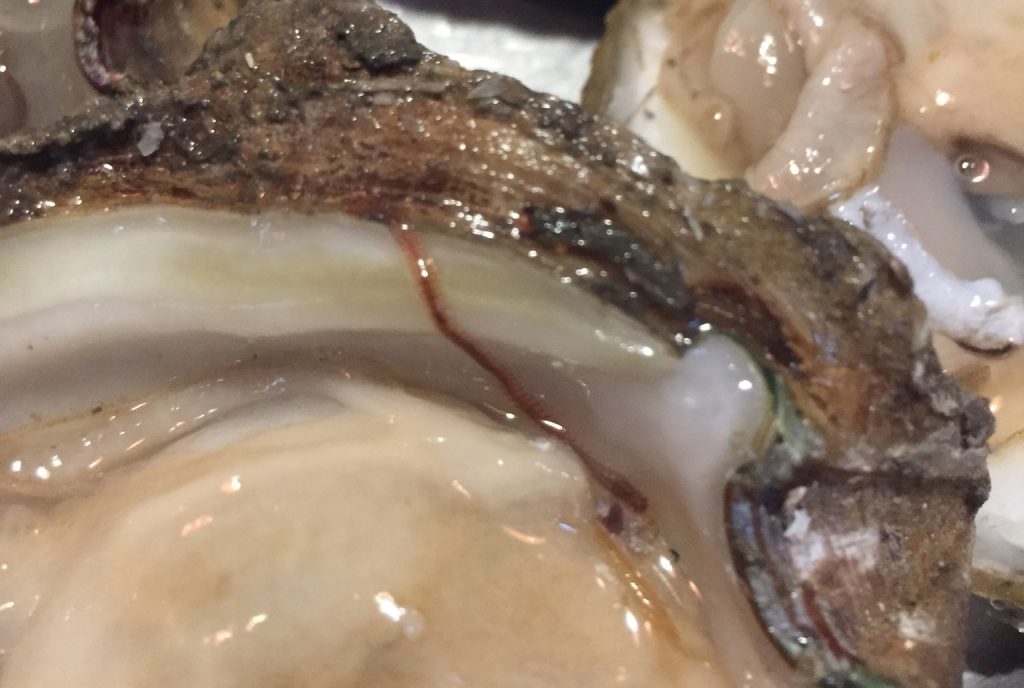

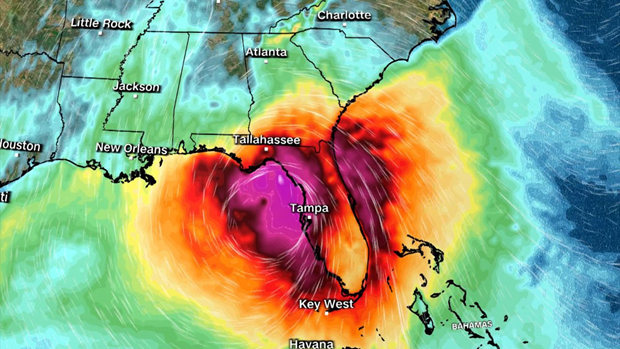

Oysters are not only powerful filterers, they also provide a home and habitat for many marine organisms. Most of these organisms will fall off while the oysters are being harvested or cleaned, but some will stay behind and can be found inside or outside of your oyster on the half shell. Seeing some of these creatures might give you the “heebie jeebies” about eating the oyster, they are perfectly safe and can either be removed or, in some cases, consumed for luck. These creatures include mud worms (Polydora websteri), “pea crabs” (Pinnotheres ostreum or Zaops ostreus), and “mud crabs” (Panopeus herbstii, Hexapanopeus angustifrons or Rhithropanopeus harrisii).

Mud Worms (Polydora websteri)

A Mud Worm in an Oyster – Louisiana Sea Grant

One of the more common marine organisms you can find on an oyster is the oyster mud worm. These worms are typically red in color and form a symbiotic relationship with the oyster. Mud worms can be found in both farmed and wild harvest oysters throughout the United States. These worms will typically form a “mud blister” and emerge when the oyster has been harvested. Even though the worms look menacing and unsightly, they are a sign of a fresh harvest and a good environment. Mud worms do not pose any threat to humans and can be consumed.

If you find a mud worm on your next oyster and are still unsure, just simply remove the worm and dispose of it. Dr. John Supan, retired professor and past director of Louisiana Sea Grant’s Oyster Research Laboratory on Grand Isle, mentioned in an article that oyster mud worms “are absolutely harmless and naturally occurring,” and “if a consumer is offended by it while eating raw oysters, just wipe it off and ask your waiter/waitress for another napkin. Better yet, if there are children at the table, ask for a clear glass of water to drop the worm in. They are beautiful swimmers and can be quite entertaining.”

“Pea Crabs” (Pinnotheres ostreum or Zaops ostreus)

“Pea Crabs” are in fact two different species of crabs lumped together under one name. Pea crabs include the actual pea crab (Pinnotheres ostreum) and the oyster crab (Zaops ostreus). These crabs are so closely associated with oysters that their species name contains some form of the Latin word “ostreum” meaning oyster! Pea crabs are known as kleptoparasites and will embed themselves into the gills of an oyster and steal food from the host oyster. Even though they steal food, they seem to pose no threat to the oyster and are a sign of a healthy marine ecosystem.

A Cute Little Pea Crab – (C)2013 T. Michael Williams

Pea crabs are soft-bodied and round, giving them the pea name. Pea crabs can be found throughout the Atlantic coast, but are more concentrated in coastal areas from Georgia to Virginia. While they might look like an alien from another planet, they are considered a delicacy and are typically consumed along with the oyster. If you are brave enough to slurp down a pea crab, you might just be rewarded with a little luck. According to White Stone Oysters, “historians and foodies alike agree that finding a pea crab isn’t just a small treat, it’s also a sign of good luck!”

“Mud Crabs” (Panopeus herbstii, Hexapanopeus angustifrons or Rhithropanopeus harrisii)

Smooth Mud Crab – Florida Shellfish Lab

Just like pea crabs, “mud crabs” is another name for two different species of crabs commonly found in oysters. These crabs, the Harris Mud Crab (Rhithropanopeus harrisii), Smooth Mud Crab (Hexapanopeus angustifrons), and the Atlantic mud crab (Panopeus herbstii) to name just a few, reach a maximum size of 2 to 8 centimeters and are hard-bodied, unlike the pea crabs. Mud crabs can survive a wide range of salinities, but need cover to survive as these crabs are common prey for most of the oyster habitat dwellers, such as catfish (Ariopsis felis), redfish (Sciaenops ocellatus), and sheepshead (Archosargus probatocephalus). These crabs are not beneficial to an oyster environment as they will seek out young oysters and consume them by breaking the shell with their strong claws. If you find a mud crab in your oyster, this is one to dispose of before consuming. However, these crabs typically live on the outside of an oyster and are typically only found when you buy a sack of oysters and do not have an effect on the quality of the oyster.

Don’t Be Afraid

Hopefully this article has helped shed some light on the creatures you might experience when shucking or consuming oysters. Here is a helpful online tool to help identify some marine organisms associated with clam and oyster farms (Click Here). While most of the organisms can be consumed, we recommend the mud crabs be disposed of due to their hard shells. Remember, some of these organisms can bring you luck and with college football season around the corner, some of us might need all the luck we can get! Bring on the pea crabs!

References Hyperlinked Above

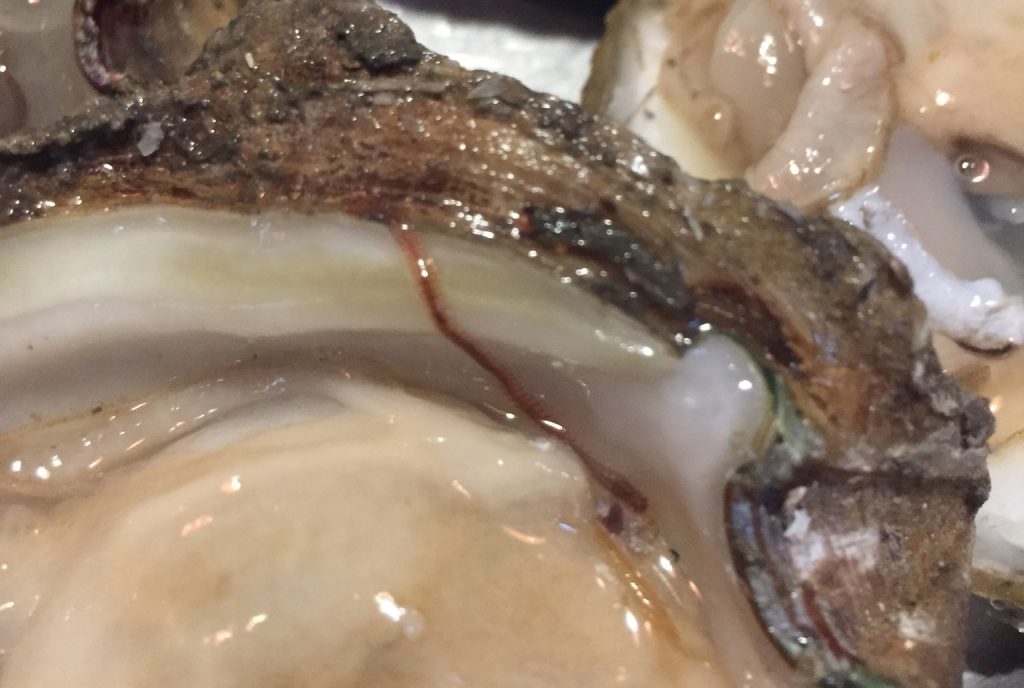

by Mark Mauldin | Aug 2, 2024

All graphics and information included are courtesy of myfwc.com.

Here in the Panhandle (FWC Zone D), we are just under 3 months away from the October 26 opening day of archery season. As we move through summer and into the home stretch of hunting season preparations it is important to be sure all hunters understand the current regulations related to deer hunting in our area – it’s more complicated than it used to be.

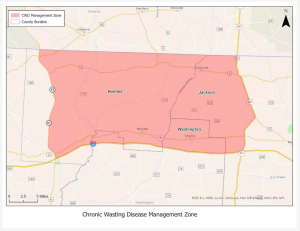

Deer Management Unit map.

From: https://myfwc.com/hunting/season-dates/dmu-d/ Click on image to make larger.

Following last summer’s discovery of Chronic Wasting Disease in Holmes County, the Chronic Wasting Disease Management Zone and its modified regulations will remain in place for the 2024-25 hunting season, but with some notable changes. The entirety of the Chronic Wasting Disease Management Zone lies within Deer Management Unit (DMU) D2. DMU-D2 is the portion of Zone D which lies north of I-10. As such, there are now some considerable differences in the hunting regulations north and south of I-10. For those of us who live along the I-10 corridor and who have opportunities to hunt on both sides of the interstate this could prove a bit confusing. The following is a discussion of the new regulations and how they differ by DMU.

New for the 2024-25 Hunting Season

The feeding of deer within the CWD Management Zone shall be allowed only during the deer hunting season (October 26, 2024 – March 2, 2025). This regulation is specific to the CWD Management Zone, not all of DMU-D2. Anywhere in Florida outside of the CWD Management Zone feeding stations must be continuously maintained with feed for at least 6 months before they are hunted over. So, unless you are hunting inside the CWD Management Zone, I hope your feeders have already been up and running for quite a while.

Chronic Wasting Disease Management Zone From: https://myfwc.com/research/wildlife/health/white-tail-deer/cwd/ Click on image to make larger.

The take of antlerless deer shall be allowed during the entire deer season in Deer Management Unit D2 on lands outside of the WMA system. For all of DMU-D2 there are no “doe days”. If it is hunting season (October 26, 2024 – March 2, 2025), it is legal to harvest antlerless deer in DMU-D2. This is quite different south of I-10, in DMU-D1, where antlerless deer may only be harvested during archery /crossbow season (Oct. 26 – Nov. 27), youth deer hunt weekend* (Dec. 7–8), and specific dates during general gun season (Nov. 30 – Dec. 1, Dec. 28–29).

Up to three antlerless deer, as part of the statewide annual bag limit of five, may be taken in DMU D2 on lands outside of the WMA system. Outside of DMU-D2, there can be no more than 2 antlerless deer included in the annual bag limit of five deer. Event if you hunt outside of DMU-D2 you still have the opportunity to harvest 3 antlerless deer in the 2024-25 season, but at least one of them must be harvested in DMU-D2. The bag limit of 5 total deer remains in place for all DMUs.

All CWD management related regulations can be found here.

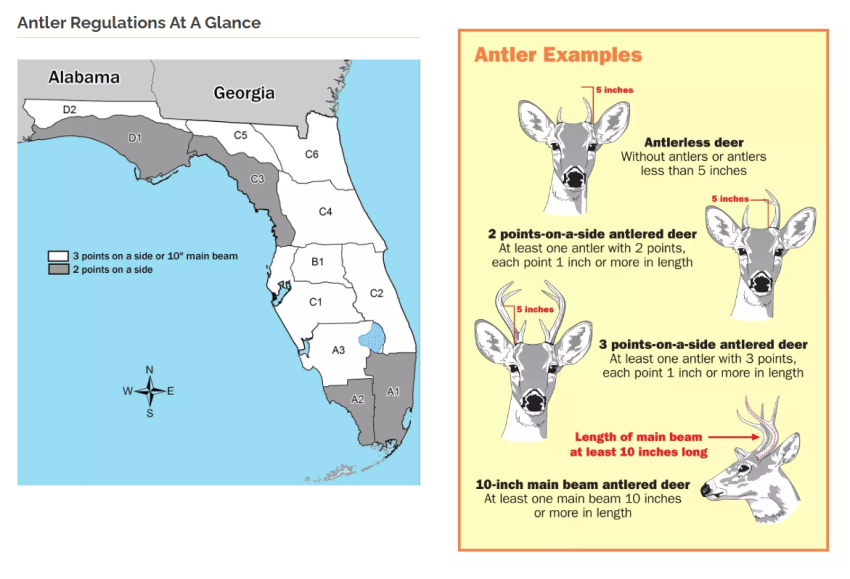

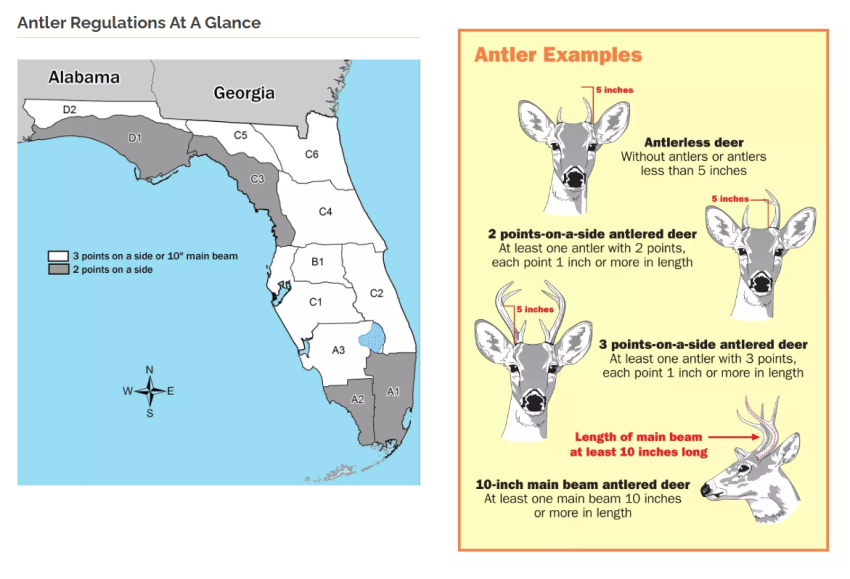

Antler Regulations

While it is not new this hunting season, it should be noted that there are different antler regulations north and south of I-10.

DMU-D1 (south of the intestate) – To be legal to take, all antlered deer (deer with at least one antler 5 inches or longer) must have an antler with at least 2 points with each point measuring one inch or more. Hunters 16 years of age and older may not take during any season or by any method an antlered deer not meeting this criteria.

DMU-D2 (north of the interstate) – To be legal to take, all antlered deer (deer with at least one antler 5 inches or longer) must have an antler with 1) at least 3 points with each point measuring one inch or more OR 2) a main beam length of 10 inches or more. Hunters 16 years of age and older may not take during any season or by any method an antlered deer not meeting this criteria.

In both DMU-D1 & D2 as part of their annual statewide antlered deer bag limit, youth 15-years-old and younger may harvest 1 deer annually not meeting antler criteria but having at least 1 antler 5 inches or more in length.

Florida Antler Regulations

From: https://myfwc.com/hunting/season-dates/dmu-d/

Harvest Reporting

Another somewhat new concept that some hunters still might not be accustomed to is Logging and Reporting Harvested Deer and Turkeys. All hunters must (Step 1) log their harvested deer and wild turkey prior to moving it from the point where the hunter located the harvested animal, and (Step 2) report their harvested deer and wild turkey within 24 hours.**

**Hunters must report harvested deer and wild turkey: 1) within 24 hours of harvest, or 2) prior to final processing, or 3) prior to the deer or wild turkey or any parts thereof being transferred to a meat processor or taxidermist, or 4) prior to the deer or wild turkey leaving the state, whichever occurs first.

Hunters have the following user-friendly options for logging and reporting their harvested deer and wild turkey:

Option A – Log and Report (Steps 1 and 2) on a mobile device with the FWC Fish|Hunt Florida App or at GoOutdoorsFlorida.com prior to moving the deer or wild turkey.

Option B – Log (Step 1) on a paper harvest log prior to moving the deer or wild turkey and then report (Step 2) at GoOutdoorsFlorida.com or Fish|Hunt Florida App or calling 888-HUNT-FLORIDA (888-486-8356) within 24 hours.