by Carrie Stevenson | Jun 4, 2018

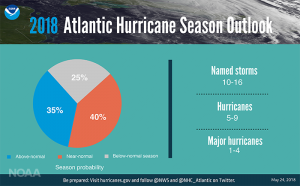

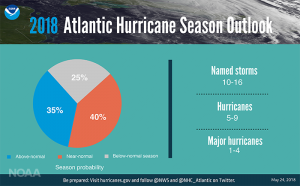

Hurricane season probability and predictions. Graphic courtesy NOAA.

The Atlantic Hurricane Season began June 1. NOAA forecasters are currently predicting a relatively normal hurricane season, expecting 10-16 named storms with 5-9 of them becoming hurricanes. While we in the Panhandle dodged the serious damages inflicted upon the state by Hurricanes Irma and Maria last year, we have already experienced our first named storm. Subtropical storm Alberto left a relatively light touch along the Florida coast, but has inundated western North Carolina with heavy rains, causing floods and mudslides.

Tree damage to homes and property can be devastating, and one of the first instincts of many homeowners when they see a big storm in the Gulf is to start trimming limbs and removing trees. However, it is wise to fully evaluate one’s landscape before making an irreversible decision. Trees are crucial for providing shade (i.e. energy savings), wildlife habitat, stormwater management, and maintaining property values.

Downed trees in a row along a hurricane-devastated street. Photo Credit: Mary Duryea, University of Florida

University of Florida researchers Mary Duryea and Eliana Kampf have done extensive studies on the effects of wind on trees and landscapes, and several important lessons stand out. Keep in mind that reducing storm damage often starts at the landscape design/planning stage!

- Select the right plant for the right place.

- Post-hurricane studies in north Florida show that live oak, southern magnolia, sabal palms, and bald cypress stand up well compared to other trees during hurricanes. Pecan, water and laurel oaks, Carolina cherry laurel and sand pine were among the least wind resistant.

- Plant high-quality trees with strong central trunks and balanced branch structure.

- Longleaf pine often survived storms in our area better than other pine species, but monitor pines carefully. Sometimes there is hidden damage and the tree declines over time. Look for signs of stress or poor health, and check closely for insects. Weakened pines may be more susceptible to beetles and diseases.

- Remove hazard trees before the wind does. Have a certified arborist inspect your trees for signs of disease and decay. They are trained to advise you on tree health.

- Trees in a group (at least five) blow down less frequently than single trees.

- Trees should always be given ample room for roots to grow. Roots absorb nutrients, but they are also the anchors for the tree. If large trees are planted where there is limited or restricted area for roots to grow out in all directions, there is a likelihood that the tree may fall during high winds.

- Construction activities within about 20 feet from the trunk of existing trees can cause the tree to blow over more than a decade later.

- Plant a variety of species, ages and layers of trees and shrubs to maintain diversity in your community

- When a tree fails, plant a new one in its place.

For more information on managing your Florida landscape in hurricane season, visit the University of Florida’s Urban Forest Hurricane Recovery page.

by Carrie Stevenson | Mar 26, 2018

Ah, the oft-ignored pine tree. They are so ubiquitous throughout the southeast, that many people consider them undesirable in a landscape. Having grown up near the “Pine Belt” of Mississippi, I figured I knew plenty about them, but this week I learned something new. While on a field tour with local foresters in the business of loblolly and longleaf pine farming, they introduced me to the pine tip moth. These insects can wreak havoc on valuable young pine trees.

Dead branch tip and needle damage caused by pine tip moths. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

Hollow space in pine tree branch created by pine tip moth. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

Female pine tip moths lay eggs on the growing end of a pine branch—particularly young, healthy loblolly and shortleaf (longleaf is rarely affected). When the eggs hatch 5-30 days later, the larvae start feeding. They tunnel into the shoot and bud of the pines, feeding on the tissue and burrowing a hollow cavity for several weeks. The larvae then pupate inside the space until becoming adult moths, exiting from the hole they created. The cycle restarts, with more adult moths, eggs and larvae.

Adult Nantucket pine tip moth Rhyacionia frustrana (Comstock). Photograph by James A. Richmond, USDA Forest Service, www.Forestryimages.org.

Two insect species are most common in our area; the subtropical pine tip moth (Rhyacionia subtropica) and Nantucket pine tip moth (Rhyacionia frustrana). The moths are reddish copper in color, small (1/2” wingspan and 1/4” body length) and active at night. Caterpillar larvae have black heads and start out with off-white bodies, but change in color to brown and orange as they age.

While this insect activity typically does not kill the tree, it does cause some die-off of terminal needles and branches. In extreme cases, it can cause tree death. Moths prefer younger trees and rarely affect pines taller than 15 feet.

If you see a cluster of dead needles at the ends of young pine branches of your property, you can easily snap off the dead tip. You will likely find the hollow space formed by the larvae, which in spring may still contain the insect. Treatment in a home landscape can managed by hand removal of infested shoots, but those in the commercial forestry business may need to install traps and consider insecticidal management.

Visit the UF School of Forest Resources and Conservation website for more information.

by Carrie Stevenson | Mar 13, 2018

The swollen base and smooth gray bark of the swamp blackgum are identifying characteristics in wetlands. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

In the river swamps of northwest Florida, the first tree to come to mind is typically the cypress. The “knees” protruding from the water are eye-catching and somewhat mysterious. Sweet bay magnolia is an easily recognizable species as well, with its silvery leaves twisting in the wind. The sweet bay (Magnolia virginiana) is a relative of the Southern magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora) in many of our yards, but its buds and leaves are smaller and it is found most often in very wet soils.

However, the often-unsung trees of the swamps are the tupelo and blackgum trees, including three species of Nyssa that go by a variety of overlapping common names. In the western Panhandle, one is most likely to see a swamp tupelo/swamp blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica var. biflora). The trees are tall—60-100’ at maturity—and have unremarkable elliptical green leaves. However, those leaves turn a lovely shade of red in the fall before dropping in the winter. Their most distinguishing characteristic year-round–but especially in the winter–is its swollen lower trunk, which expands at the base to twice or three times the size of the remaining trunk. These buttresses, also found on bays (more subtly) and cypress (along with knees), are an adaptation to stabilizing a tree growing in large pools of wet, loose soil or standing water.

A young blackgum tree in full fall color. Photo credit: UF IFAS Extension

The swamp tupelo has two more relatives in the region, water tupelo (Nyssa aquatica) and Ogeechee lime/tupelo (Nyssa ogeche), both with hanging edible (but tart) fruit. In the early days of William Bartram’s explorations of Florida, explorers used the acidic Ogeechee lime as a citrus substitute. Typically found in a narrower range from Leon County east to southeast Georgia, the Ogeechee lime is the nectar source for the famous and prized multi-million dollar tupelo honey industry.

Blackgum or tupelo trees (missing the “swamp” in front of their common name—aka Nyssa sylvatica) are actually excellent landscape trees that can thrive in home landscapes. Like their swamp cousins, the trees perform well in slightly acidic and moist soil, although they can thrive even in the disturbed, clay-based soils found in many residential developments. Blackgums can grow in full sun or shade, are highly drought tolerant, and can even handle some salt exposure. Their showy fall color is a nice addition to many landscapes, and the fruit are an excellent source of nutrition for native wildlife.

by Carrie Stevenson | Jan 25, 2018

Ghost plant/Indian pipes emerging from the ground. Photo credit: Carol Lord, UF IFAS Extension

Imagine you are enjoying perfect fall weather on a hike with your family, when suddenly you come upon a ghost. Translucent white, small and creeping out of the ground behind a tree, you stop and look closer to figure out what it is you’ve just seen. In such an environment, the “ghost” you might come across is the perennial wildflower known as the ghost plant (Monotropa uniflora, also known as Indian pipe). Maybe it’s not the same spirit from the creepy story during last night’s campfire, but it’s quite unexpected, nonetheless. The plant is an unusual shade of white because it does not photosynthesize like most plants, and therefore does not create cholorophyll needed for green leaves.

In deeply shaded forests, a thick layer of fallen leaves, dead branches, and even decaying animals forms a thick mulch around tree bases. This humus layer is warm and holds moisture, creating the perfect environment for mushrooms and other fungi to grow. Because there is very little sunlight filtering down to the forest floor, the ghost flower plant adapted to this shady, wet environment by parasitizing the fungi growing in the woods. Ghost plants and their close relatives are known as mycotrophs (myco: fungus, troph: feeding).

Ghost plant in bloom at Naval Live Oaks reservation in Gulf Breeze, Florida. Photo credit: Shelley W. Johnson

These plants were once called saprophytes (sapro: rotten, phyte: plant), with the assumption that they fed directly on decaying matter in the same way as fungi. They even look like mushrooms when emerging from the soil. However, research has shown the relationship is much more complex. While many trees have symbiotic relationships with fungi living among their root systems, the mycotrophs actually capitalize on that relationship, tapping into in the flow of carbon between trees and fungi and taking their nutrients.

Mycotrophs grow throughout the United States except in the southwest and Rockies, although they are a somewhat rare find. The ghost plant is mostly a translucent shade of white, but has some pale pink and black spots. The flower points down when it emerges (looking like its “pipe” nickname) but opens up and releases seed as it matures. They are usually found in a cluster of several blooms.

The next time you explore the forests around you, look down—you just might see a ghost!

by Carrie Stevenson | Nov 6, 2017

A wooden bin is easy to use for composting kitchen and yard waste. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson

Fall is the time of year many of us spend countless hours raking leaves and pine straw, piling them up, watching kids jump into the piles (then re-raking!), and bagging them up for disposal. However, what you may not have considered is that all of those materials are ideal fertilizer for your lawn and garden.

Composting is an excellent way to recycle yard waste, and now that leaves are dropping, you’ve got plenty of material to recycle. Vegetable gardens and landscapes alike can benefit from a generous dose of compost now and then. A free source of much-needed nutrients in our often nutrient-poor sandy soil, organic-rich compost also loosens tight, compacted soils and helps them hold nutrients and water.

So what is compost? Basically, compost is what’s left of organic matter after microbes have thoroughly decomposed it. Among the compostable organic materials available to most homeowners are leaves, grass clippings, twigs, chopped brush, straw, sawdust, vegetable plants, culled vegetables from the garden, fruit and vegetable peelings and coffee grounds (including the paper filter) from the kitchen. Don’t add table scraps with meats or oils to your compost pile—meats especially will attract animals. Contrary to popular opinion, compost piles don’t typically smell—but if you do have an odor come from decomposing vegetables, turning the compost pile and adding dirt, grass clippings or leaves will eliminate any smell.

The organisms that do the actual composting are bacteria and fungi are microscopic, although you will also find worms and arthropods in a good compost bin. A number of companies sell “composting microbes,” but you don’t need them. Fortunately, plenty of these microbes are around already. To get started, just mix a few scoops of garden soil or compost from a previous batch into the compost pile will provide all the microbes you need to start the process. The microbes just need water, oxygen and nutrients to grow and multiply.

Rainfall will provide most of the needed moisture. You may need to hand water the pile on occasion, too, during dry times. For best results, keep the pile moist but not soggy; if you pick up a handful it should not crumble away nor drip water when squeezed. The right mix of organic matter can provide all the nutrients needed. Alternate using brown (leaves, straw) and green materials (grass clippings, vegetables) in your compost bin to provide the needed amounts of carbon and nitrogen. If the pile seems to be decomposing too slowly, raise the nitrogen level by adding a few more green materials or a handful of granular fertilizer. And the more you turn the pile, the faster it will decompose.

There are many ways to contain your composting materials, from a simple pile to a solar-heated, rotating bin and everything in between. For more information on composting and compost bin options, please see this University of Florida Extension article.