by Molly Jameson | Oct 28, 2021

As you garden this fall, check out the North Florida Vegetable Gardening Guide, compiled by UF/IFAS Leon County Extension.

Getting into vegetable gardening, but don’t know where to start?

Even experienced gardeners know there’s always more to learn. To help both beginners and advanced gardeners find answers to their questions, the UF/IFAS Leon County Extension Office put together the North Florida Vegetable Gardening Guide. It incorporates multiple resources, including articles, planting calendars, photos, and UF/IFAS EDIS publications.

The North Florida Vegetable Gardening Guide covers the many aspects of vegetable gardening, including how to get started, site selection, insects and biodiversity in the garden, soil testing, composting, cover crops in the garden, irrigation, and more.

You can click here to view the digital version of the guidebook. We also have physical copies of the guide available at the UF/IFAS Leon County Extension Office (615 Paul Russell Rd., Tallahassee, FL 32301).

Happy fall gardening!

by Molly Jameson | Aug 18, 2021

Carrots need enough space so as not to compete for light, nutrients, or moisture. Photo by Full Earth Farm.

Of all the garden veggies, carrots are very close to the top of my list of favorites to grow. They can be directly seeded into the garden, need no pruning or staking, can hold up magnificently in the cold, have few pest problems, are easy to harvest, can be eaten raw or cooked, and they are, of course, delicious.

Hand-seeding carrots can be a challenge, as the seeds are very small. Photo by Molly Jameson.

Carrots are in the Apiaceae, or umbel family, along with cilantro, celery, fennel, parsley, and dill. Flowers in the umbel family grow as short flower stalks which spread from one point, like that of an upside-down umbrella, hence their name. If the carrot root is not harvested, the plant will produce beautiful umbrella-like inflorescences the following year, as carrots are biennial.

When planting carrots, there are some important aspects to keep in mind. Here in Florida, carrots thrive in our cool season. They prefer soil temperatures to be less than 80°F for good germination and air temperatures below 75°F for best growth. Therefore, waiting until mid-September through October to seed will yield better germination and growth.

One of the biggest mistakes one can make in the garden is neglecting to thin seedlings. And carrots – whose seeds are a mere millimeter in length – are one of the prime culprits.

An individual carrot needs one to three inches of soil space, depending on the variety, to grow to full maturity and not compete for light, nutrients, or moisture. This, however, does not mean that you must only plant one carrot seed per one to three inches. In fact, carrots should be seeded one-half inch apart, especially when day temperatures are above 75°F, as you may have spotty germination. But the key is proper thinning. Carrots take between seven to 21 days to germinate, so be sure to give them time, and be sure to keep the area consistently moist, but not water-logged.

Depending on the variety, carrots need one to three inches per plant. Photo by Beth Bolles.

Once germinated, it is crucial to make your first thinning. Find the seedlings that are less than an inch apart and simply cut their stems at the soil line using either a sharp fingernail or garden sheers. Depending on the variety of carrot and seeding density, you may need to make another thinning to ensure the carrots have enough room to prosper.

I know it can be emotionally challenging to remove growing seedlings from your garden – but remember – it’s for the greater carrot good!

by Molly Jameson | Jul 15, 2021

Join us via Zoom on Saturday, August 7, for our Leon County Seed Library Virtual Workshop. Graphic by Molly Jameson.

Join Us August 7 for the 2021 Leon County Seed Library Virtual Workshop

Planting vegetable seeds and growing a garden is a great way to get outdoors and appreciate nature. Since 2015, the Leon County Public Library has supported gardeners in Leon County by providing vegetable seed packets for patrons to take home and plant in their gardens.

To kick off the Fall 2021 Seed Library, agents with UF/IFAS Leon County Extension are hosting the Leon County Seed Library Virtual Workshop on Saturday, August 7, from 10:00 a.m. to 12:00 p.m. via Zoom.

During the virtual workshop, Extension agents will discuss planting seeds, growing vegetables, and how to incorporate veggies into healthy meals and snacks. The workshop coincides with the first day the seeds in the Fall 2021 Seed Library will become available. Residents of Leon County can check out three sample seed packets per month with their library cards from all Leon County library branches.

Even if you are not a resident of Leon County, everyone is welcome to join us at the virtual workshop. Along with the gardening portion of the workshop, there will also be a live virtual cooking demonstration featuring vegetables available in the Fall 2021 Seed Library Program.

For more information about the Leon County Seed Library Virtual Workshop, please visit our Eventbrite page: https://seedlibraryworkshop2021.eventbrite.com. There is no cost to attend the workshop, but registration is required.

If you are a resident of Leon County, all you need is your Leon County library card to check out the vegetable seeds. Don’t have a library card? No problem! Leon County residents can apply online at the LeRoy Collins Leon County Public Library online card application page here: https://lcpl.ent.sirsi.net/custom/web/registration/.

Here is the list of the vegetable seed varieties that will be available starting August 7: Common Arugula, Waltham 29 Broccoli, Chantenay Red Core Carrots, Michihili Chinese Cabbage, Slo-bolt Cilantro, Alabama Blue Collards, Early White Vienna Kohlrabi, Rocky Top Salad Blend Lettuce, Pink Beauty Radishes, and Tokinashi Turnips.

by Molly Jameson | Jun 3, 2021

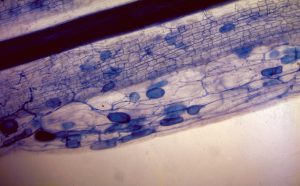

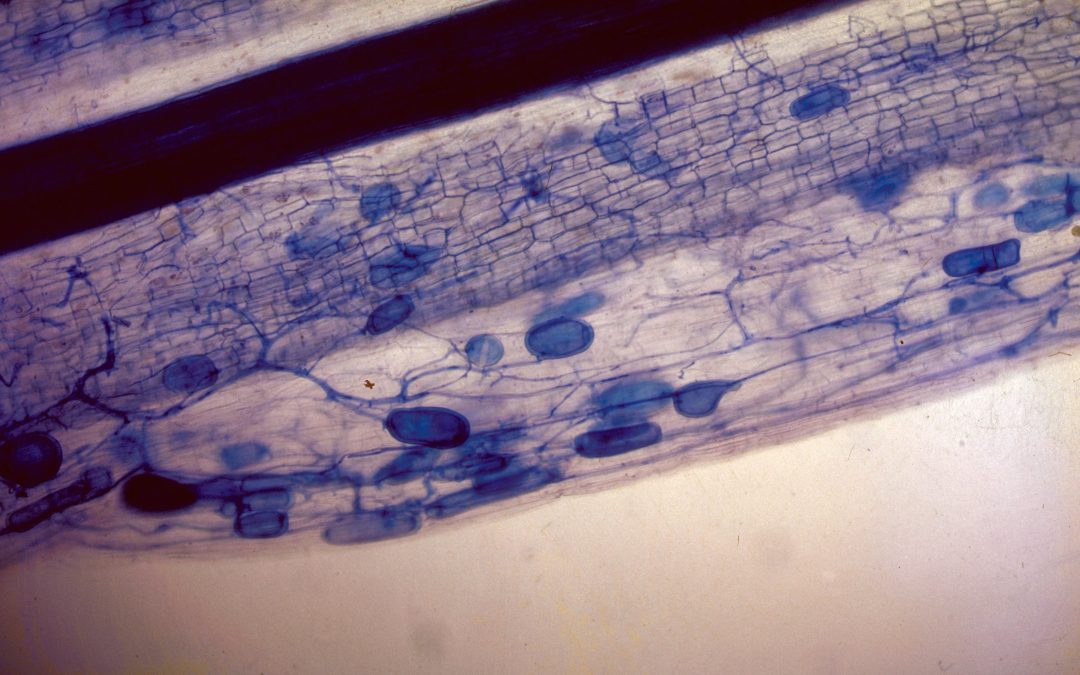

Mycorrhizal fungi develop mutually beneficial symbiotic relationships with plant roots. Photo by Edward L. Barnard, Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Bugwood.org.

If you have taken an elementary school science class, you have probably learned the basics of photosynthesis. In case you are a bit rusty, photosynthesis is the process by which plants capture sunlight to manufacture their food. They absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and water from the soil. With these ingredients, they create carbohydrates, or sugars, that supply the energy to grow and develop.

As you can imagine, this energy is vital to the health of the plant. But fascinatingly, plants expel between 20 and 40 percent of these sugars from their roots into the surrounding area around the roots. The sugars that the plant releases, along with amino acids, organic acids, enzymes, and other substances, are called root exudates. The area just inside the root where the sugars are released, and the area just outside the root where the sugars end up, is called the rhizosphere.

But why would a plant waste this energy? This is because they derive benefits from the unique microbial population that inhabits the rhizosphere. Plant roots are limited by the amount of nutrients they can take up in the soil. By feeding microorganisms their sugars, they are essentially recruiting workers to help them scavenge for nutrients in areas that they cannot access on their own.

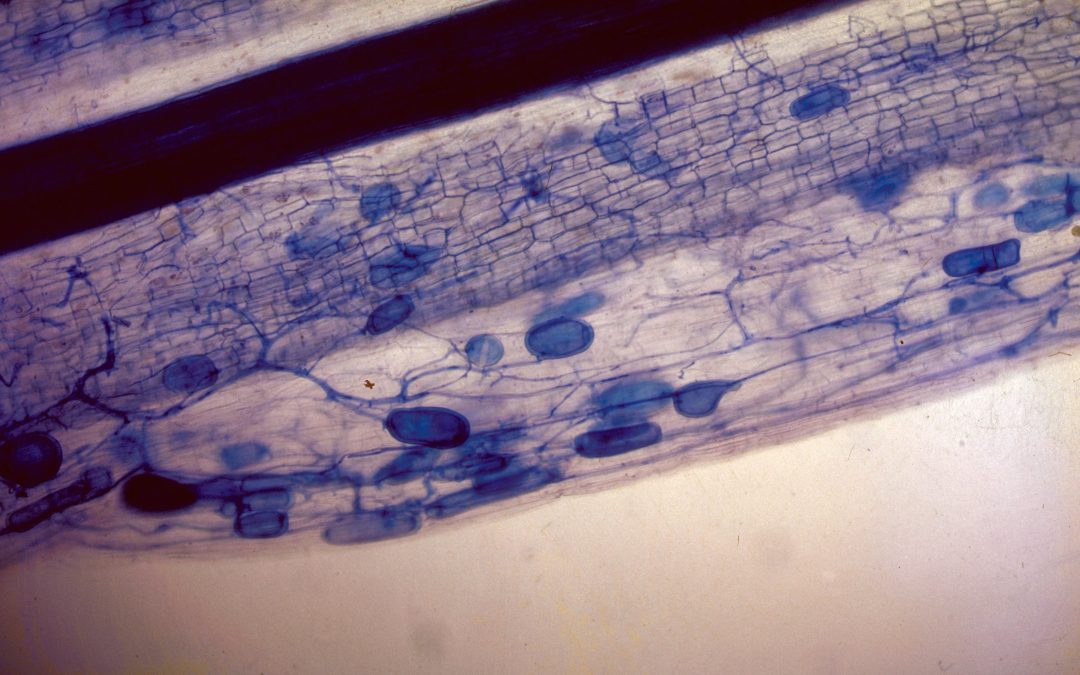

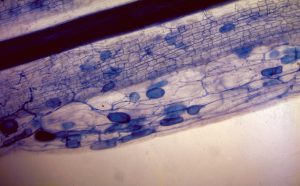

A microscopic image of mycorrhizal fungi in black walnut. Photo by Robert L. Anderson, USDA Forest Service, Bugwood.org.

Bacterial colonies, which are types of microorganisms, establish themselves within the rhizosphere and feed on the root exudates, allowing the bacteria to multiply. Along with the sugars they take in from the root exudates, they also take in nutrients from the soil. The waste that is produced by the bacteria is rich in bioavailable plant nutrients, which the plant then uses, creating a plant-microbe symbiotic relationship where everyone wins.

Another type of specialized microorganism, mycorrhizal fungi, also develops a symbiotic relationship with plants. Its meaning is within its name, as “myco” literally means fungus and “rhiza” literally means root. There are an estimated 50,000 fungal species that form these beneficial relationships with approximately 95 percent of plant families.

The mycorrhizal fungal hyphae, which are tiny fungal filaments one cell thick, do not have chlorophyll and are therefore not able to photosynthesize. Instead, the fungal networks have a large surface area that allows them to be particularly good at extracting nutrients from the soil. This enables them to access nutrients that plant roots would not be able to access on their own. The fungi drill into the plant root and trade these nutrients, along with water, with the plant in exchange for the sugary root exudates. In this way, both the fungi and the plant benefit from the relationship. Interestingly, these types of relationships will only develop once the plant releases particular root exudates that attract the microorganisms they are seeking. In essence, the mycorrhizal fungal hyphae will not associate with the root until they are invited.

Along with root exudates, root hairs and other plant cells accumulate within the rhizosphere as they grow and die throughout the plant’s life cycle. The combination of the root exudates, dead root hairs, and dead plant cells creates essentially a compost pile within the rhizosphere. This combination of substances establishes an environment where beneficial microorganisms can thrive, and a plant can maximize its nutrient uptake capacity.

Amazingly, there can be up to a billion bacteria and several yards of fungal hyphae living in just one teaspoon of soil! Of course, not all microorganisms are beneficial to the plant. But remarkably, plants have developed many ways in which they benefit, and ultimately thrive, in this diverse soil ecosystem.

As humans, we continue to learn more and more about these complicated and interesting interactions taking place in the soil beneath us. And the more we learn, the more we discover just how important these diverse ecosystems are to the health of the food web, and therefore, to the health of our planet as a whole.