by Blake Thaxton | Dec 16, 2013

This fall, the Gulf Coast Small Farms and Alternative Enterprises Team put in a fall vegetable demonstration at UF/IFAS West Florida Research and Education Center in Jay, Florida. The demonstration had several fall crops such as spinach, swiss chard, lettuce, broccoli, cauliflower, carrots, turnips, rutabaga, kale, and collards. Several of the recommended varieties were grown so that small farmers and home gardeners could visually inspect the different varieties and see what they may want to grow next fall. The recommended varieties came from the 2012-2013 Vegetable Production Handbook of Florida and the 2013 Southeast US Vegetable Crop handbook.

So you can also experience this demonstration, below are pictures of some of the varieties being grown.

Swiss Chard

The swiss chard has done outstanding, although the low temperatures recently did produce cold damage. The swiss chard that was grown in the high tunnel structures has thrived.

Lettuce

Lettuce

Ouredgeous (romaine), Cherokee (loose leaf), and Ithica (heading) were all grown. Below is a picture of Ithica which has done well, although slow growing up to this point. The cold caused some damage on Ithica as well.

Carrots

Carrots

Suger Snax 54, Purple Haze, and Apache were the varieties grown. They have all done well but appear to have grown much slower than the literature indicates. Beautiful none the less!

Broccoli

Cauliflower

If you want to have a closer look at the varieties, call for a walk through (850)623-3868

If you want to have a closer look at the varieties, call for a walk through (850)623-3868 or email at bthaxton@ufl.edu. Their will be a field day held tomorrow Wednesday, December 18th, at this demonstration site for Master Gardeners and Small Farmers. Click here to register!

or email at bthaxton@ufl.edu. Their will be a field day held tomorrow Wednesday, December 18th, at this demonstration site for Master Gardeners and Small Farmers. Click here to register!

by Carrie Stevenson | Dec 9, 2013

How much is a 400-year old live oak tree worth? Can you buy one online, with free shipping, and charge it to the credit card? Pick one up at the local home improvement store? Ask Santa? Of course not. When admiring a tree that size, we have an innate sense of its value, but we would often have a hard time expressing it in dollars. How about a cluster of trees in a wooded lot? Are they worth more than the dollar store being built there? We are conditioned to appreciate the value of things because there’s a price tag on them. Unfortunately, natural phenomena do not have price tags, and many things that are “free” are often perceived to have no real value.

Planting a tree is an excellent way to insure clean air and water in the future. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson

Trees, however, have value far beyond the price one might pay at a plant nursery. Their roots absorb polluted storm-water runoff, the primary cause of decreased water quality in Florida. Their leaves take in carbon dioxide and release the very oxygen we breathe. Providing homes for wildlife, fruit and nuts for human and animal consumption, compounds that form the basis of countless medications—trees provide innumerable benefits to ecosystems both local and worldwide. If a local government were to construct a facility or method that could filter the air and water at the same efficiency and volume of the trees in ones county, it would cost the community millions.

This street tree in Chicago was given a price tag to raise awareness of its value. Photo credit: Eric Stevenson

But how is is possible to capture these benefits in a way that we can relate to? Luckily, a partnership between arborists, engineers, and researchers with private industry, the US Forest Service, and the USDA has resulted in an excellent online tool called the National Tree Benefits calculator. Based on software called “i-Tree,” the calculator allows anyone to enter their zip code, choose from a list of common tree species, and using the diameter of a single tree, calculate its economic value. For example, a 15-inch live oak tree at the Escambia Extension office provides an annual benefit of $79 every year, increasing in value as it grows in girth and height. The website delves deeper into the tree’s value, placing storm-water uptake value at $23.77, electricity savings at $15.23, and the capability to remove 607 pounds of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

Extension Agents are currently working with youth in Escambia County to calculate these values for trees on their school campuses, local parks, and yards. When we’re finished, we will hang actual price tags on the trees showing their annual economic value to showcase these facts to residents of the community.

Interested in what kind of economic benefit that magnolia in the front yard is giving you? Check it out yourself at www.treebenefits.com, and let your neighbors know how valuable those trees can really be.

by Alex Bolques | Nov 25, 2013

In search of an entry point into a home: Leaf footed bugs congregating on house siding in search of a warm sheltered environment to spend winter. Courtesy of Bill Stinson

Leaf footed bugs are pests of many seed, fruit, vegetable and nut crops. They get their name from the leaf shape of their back legs. The insect is dark brown to black and about an inch long. Like ladybird beetles, leaf footed bugs can invade your home in the fall in search of a warm sheltered environment to spend winter. In some cases, this may be inside your home. However, unlike ladybird beetles, which can invade a home by the hundreds, leaf footed bugs numbers are considerably less.

In both cases, they enter the home through openings such as cracks, crevices, crawl spaces, attics, ridge vents etc. Once inside, they do not cause any damage, eat, drink or reproduce. Instead, they go into what is called diapause, a dormant state. If you encounter them in living spaces of the home, a common management practice is to collect them by hand or mechanically by removing them with a vacuum cleaner and then releasing them outside. Leaf footed bugs are related to stink bugs and will give off an odor if crushed or held to long in your hand. Once spring arrives, they will become active and you may find them roaming around living spaces again. Use the same control tactic to help them find their way to the outside of the home.

It should be noted that ladybird beetles are considered a beneficial insect that feeds on crop-damaging insects such as aphids, mealy bugs, and white flies. On the other hand, leaf footed bugs are a serious pest of cotton and a direct pest of many seed, fruit, vegetable and nut crops.

Reference

Stink Bugs and Leaf-footed Bugs Are Important Fruit, Nut, Seed and Vegetable Pest

by Matthew Orwat | Nov 18, 2013

On the night of November 13th, a mild freeze of 30°F occured in parts of Northwest Florida. Don’t be caught without a citrus protection plan !

Satsuma Tree protected with micro-irrigation. Image Credit: UF IFAS Jackson County Extension

How cold does it have to get before citrus in Northwest Florida needs to be protected? A concrete answer to this question does not exist. Growers and home gardeners alike must consider several factors including type of citrus grown and the location of the citrus.

Below are a few quick facts to assist growers and home gardeners in determining whether to protect or not to protect their citrus:

- Certain citrus trees such as lime, pomelo, grapefruit, sweet orange, lemon and citron will definitely need protection or need to be moved into a sheltered area. Individuals that grow these types on a consistent basis either wrap their trees with protective covers each season or grow them in containers and move them into greenhouses.

- The meyer lemon, which is in reality a lemon-sweet orange hybrid, is a tree that was introduced to the united states in 1908. Mature dormant meyer lemons can be hardy down to 20°F, with fruit hardy to 26°F. Immature trees, or those that have not reached dormancy, should be protected. Covers made of cloth should be large enough to touch the ground so that heat from the soil can help keep the tree warm.

- Generally, satsuma are cold tolerant down to 15° F, but young trees or trees yet to achieve dormancy are usually only tolerant to 26°F. Fruit should not sustain damage from freezing temperatures above 25°F. Extreme winds sometimes make the effects of freeze events worse, so it is always better to err on the side of protection if the trees are planted in an exposed site.

- Kumquats are the most cold tolerant citrus type grown in Northwest Florida, so protection is not required unless freeze events reach 20°F.

Additional facts to assist the grower or home gardener with citrus protection:

- Plant trees on a south-facing slope, south of windbreaks, on the south side of a structure or under a light canopy if possible. South facing slopes block harmful cold winds. Structures offer radiant heat which aids in the protection of citrus trees. Additionally, light over-story pine canopies allow sufficient sunlight through while reducing frost damage.

- Wrap the trunk with commercial tree wrap or mound soil around the base of the tree up to 2 feet. This will protect the graft of the young tree. Thus, if the branches freeze the graft union will be protected.

- Cover the tree with a cloth sheet or blanket. For additional protection, large bulb Christmas lights can be placed around the branches of the tree. This will increase the temperature under the cover by several degrees. Be sure to use outdoor lights and outdoor extension cords to avoid the potential of fire.

- Water citrus trees. Well watered trees have increased cold hardiness. Do not over-water. If the ground is moist, it is not necessary to water.

- Frames may be installed around young trees to hold the cover. This option keeps the blanket or sheet from weighing down the branches.

- For large production areas, micro-irrigation is an option. This practice will protect citrus trees up to 5 feet, but must be running throughout the entire freeze event. For additional information read this publication on micro-sprinkler irrigation.

- Always remember to remove cold protection once the temperature rises so that the trees do not overheat.

- Do not cover trees with plastic tarp, these will not protect the tree and can “cook” the tree once the sun comes out.

For additional information, contact your local extension office.

by Larry Williams | Nov 18, 2013

Florida maple beginning to exhibit fall color. Photo credit: Larry Williams

Although Florida is not known for the brilliant fall color enjoyed by some of our northern neighbors, we do have a number of trees that provide some fall color for our North Florida landscapes.

Our native flowering dogwood consistently provides some change in color before dropping its leaves. You can expect a red to maroon color in many of the dogwood leaves during fall.

Some of North Florida’s native maples produce good color each fall. Red maple provides brilliant red, orange and sometimes yellow leaves. The native Florida Maple, Acer saccharum var. floridum, displays a combination of bright yellow and orange color during fall. And there are many Japanese maples that provide striking fall color.

Another excellent native tree is Blackgum, Nyssa sylvatica. This tree is a little slow in its growth rate but can eventually grow to seventy-five feet in height. It deserves more use in our landscapes. It always provides a bright show of red to deep purple fall foliage.

Crape myrtle gives varying degrees of orange, red and yellow in its leaves before they fall. There are many cultivars – some that grow several feet to nearly thirty feet in height.

Young red maple with fall foliage. Photo credit: Larry Williams

There are a number of dependable oaks for fall color, too. Shumard, Nuttall and Turkey are a few to consider. These oaks have dark green deeply lobed leaves during summer turning vivid red to orange in fall. Turkey oak is sometimes referred to as “scrub” oak and is common on our deep sandy soils. It is short-lived as compared to most oak species, living for fifteen to thirty years before it starts to decline and die. It does not grow very large in height or trunk diameter and is not grown or sold much because it is so common in the wild. Nuttall and Shumard are becoming better available.

Sweetgum is another common native tree to considering for fall color. But some people dislike this tree because of the one to three-inch round fruit (called sweetgum balls) that it produces, which can be a nuisance as they fall on the ground around the tree. And this tree produces large surface roots that can be a problem for mowers, nearby curbs and sidewalks. But its star-shaped leaves turn bright red, purple, yellow or orange in fall.

Our native yellow poplar and hickories provide bright yellow fall foliage. And it’s difficult to find a more crisp yellow than fall ginkgo leaves.

These trees represent just a few choices for fall color. Including one or several of these trees in your landscape will allow you to enjoy the color of fall for many years right in your own backyard.

by Taylor Vandiver | Nov 11, 2013

As I made a visit back to my hometown in North Alabama I was reminded of the subtle changes from fall into winter, which are not always apparent to me living in Tallahassee: the vibrant palette of leaves as they make their permanent descent until spring, the litter of spent cotton along each highway and county road and the annual pecan harvest that has been a tradition in my family for as long as I can remember.

Due to the variations in climate and topography from upper Alabama to the panhandle of Florida, our seasons can differ greatly. However, I know of one entity that remains a constant and that is the availability of pecans. Pecan trees (Carya illinoinensis) are a common sight throughout the South. They can be spotted as far west as Texas and as far north as Illinois. The pecan tree is native to the Mississippi floodplain, which has deep, fertile, well-drained soils. Before the arrival of Europeans, Native Americans used pecans as a primary food source for thousands of years.

What’s more, pecans have major economic value. The annual value of pecans in the United States is estimated at 200 to 500 million dollars. Florida produces from five to ten million pounds of pecans annually. The majority of that pecan production acreage (6,500 acres) can be found in North Florida. While the nut is the main attractant of the tree, there’s not much that warms the heart more than seeing pecan pie at the dessert table on Thanksgiving.

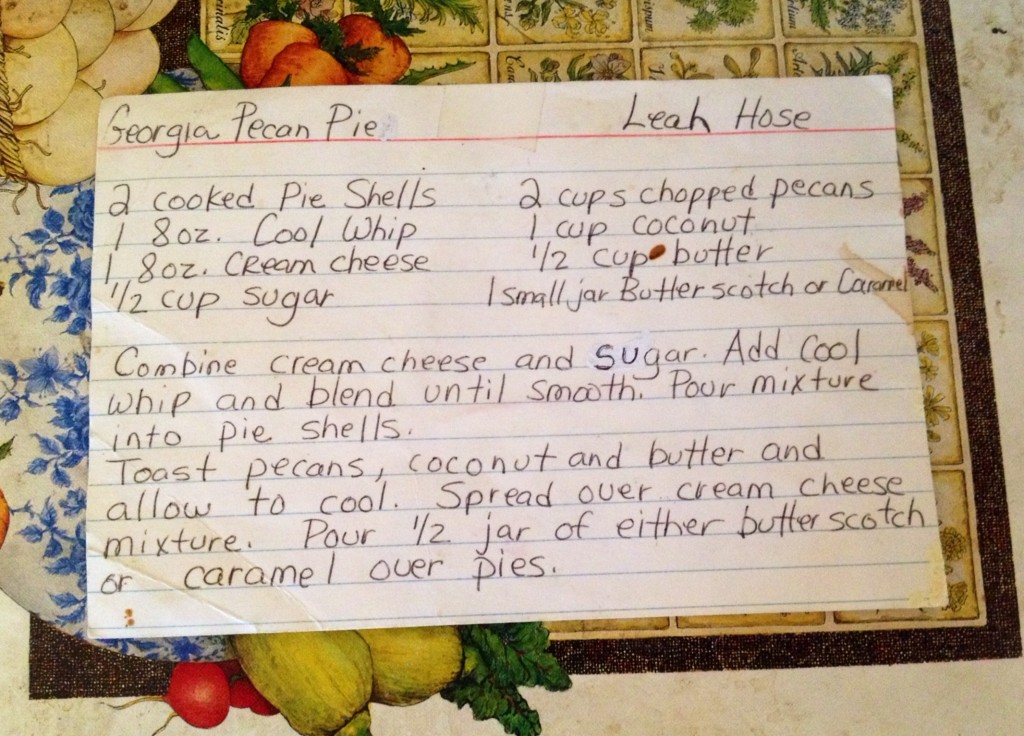

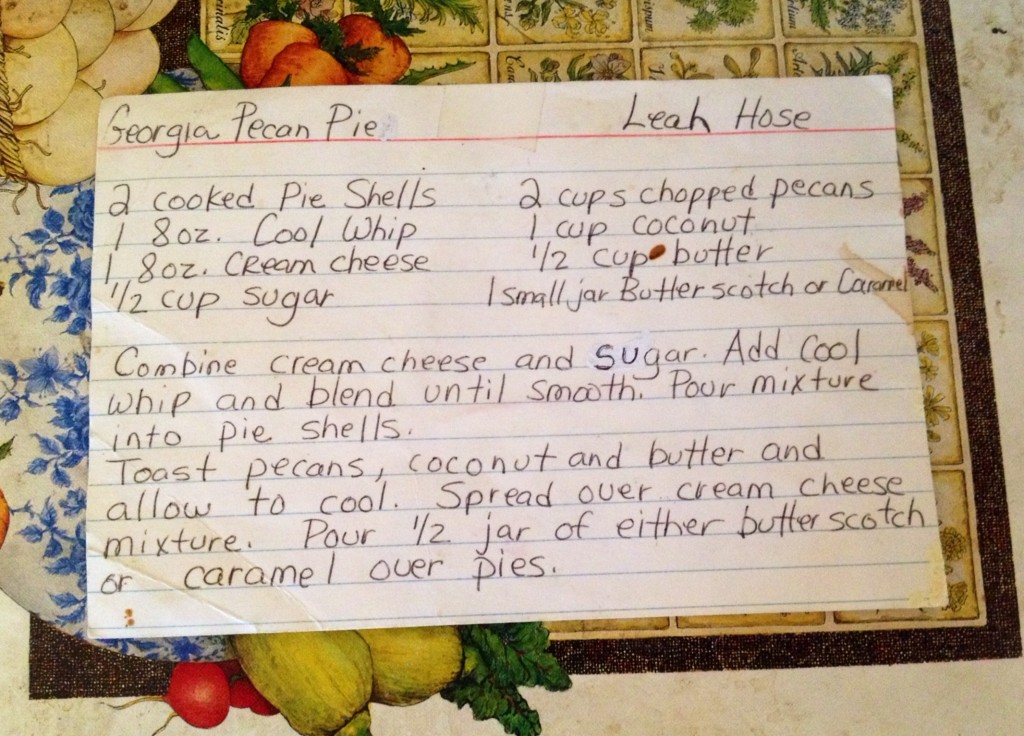

A well worn recipe for southern pecan pie that has been passed down through my family.

Pecan trees are deciduous, which means that they drop their leaves in the winter. An additional consideration for those planning to install pecan trees is to be aware that they are wind-pollinated and that their male and female flowers often do not mature at the same time. Therefore, in order to ensure the possibility of high yields, two or more cultivars should be planted together for cross-pollination.

Be sure to choose a variety like ‘Elliot’ or ‘Curtis’ that has good disease resistance, is suited for North Florida and will cross-pollinate well. Plant pecans during the colder months to allow for root growth before spring. The optimum soil pH for pecans is 5.5 to 6.5. At the lower end of this range, micronutrient deficiency symptoms should be less common. Pecan trees should start producing decent crops in six to twelve years. A tree at maturity can reach up to seventy feet tall so plan spacing and placement accordingly.

Pecan tree planted by my great-grandparents in Monrovia, Alabama.

For more information please consult Pecan Cultivars for North Florida or contact your local UF IFAS county extension office.

Lettuce

Lettuce  Carrots

Carrots

If you want to have a closer look at the varieties, call for a walk through (850)623-3868 or email at bthaxton@ufl.edu. Their will be a field day held tomorrow Wednesday, December 18th, at this demonstration site for Master Gardeners and Small Farmers. Click here to register!

If you want to have a closer look at the varieties, call for a walk through (850)623-3868 or email at bthaxton@ufl.edu. Their will be a field day held tomorrow Wednesday, December 18th, at this demonstration site for Master Gardeners and Small Farmers. Click here to register!