by Carrie Stevenson | Jun 4, 2018

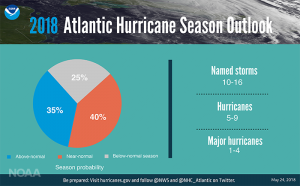

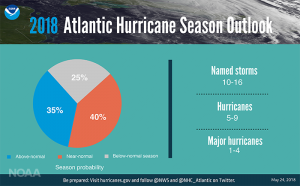

Hurricane season probability and predictions. Graphic courtesy NOAA.

The Atlantic Hurricane Season began June 1. NOAA forecasters are currently predicting a relatively normal hurricane season, expecting 10-16 named storms with 5-9 of them becoming hurricanes. While we in the Panhandle dodged the serious damages inflicted upon the state by Hurricanes Irma and Maria last year, we have already experienced our first named storm. Subtropical storm Alberto left a relatively light touch along the Florida coast, but has inundated western North Carolina with heavy rains, causing floods and mudslides.

Tree damage to homes and property can be devastating, and one of the first instincts of many homeowners when they see a big storm in the Gulf is to start trimming limbs and removing trees. However, it is wise to fully evaluate one’s landscape before making an irreversible decision. Trees are crucial for providing shade (i.e. energy savings), wildlife habitat, stormwater management, and maintaining property values.

Downed trees in a row along a hurricane-devastated street. Photo Credit: Mary Duryea, University of Florida

University of Florida researchers Mary Duryea and Eliana Kampf have done extensive studies on the effects of wind on trees and landscapes, and several important lessons stand out. Keep in mind that reducing storm damage often starts at the landscape design/planning stage!

- Select the right plant for the right place.

- Post-hurricane studies in north Florida show that live oak, southern magnolia, sabal palms, and bald cypress stand up well compared to other trees during hurricanes. Pecan, water and laurel oaks, Carolina cherry laurel and sand pine were among the least wind resistant.

- Plant high-quality trees with strong central trunks and balanced branch structure.

- Longleaf pine often survived storms in our area better than other pine species, but monitor pines carefully. Sometimes there is hidden damage and the tree declines over time. Look for signs of stress or poor health, and check closely for insects. Weakened pines may be more susceptible to beetles and diseases.

- Remove hazard trees before the wind does. Have a certified arborist inspect your trees for signs of disease and decay. They are trained to advise you on tree health.

- Trees in a group (at least five) blow down less frequently than single trees.

- Trees should always be given ample room for roots to grow. Roots absorb nutrients, but they are also the anchors for the tree. If large trees are planted where there is limited or restricted area for roots to grow out in all directions, there is a likelihood that the tree may fall during high winds.

- Construction activities within about 20 feet from the trunk of existing trees can cause the tree to blow over more than a decade later.

- Plant a variety of species, ages and layers of trees and shrubs to maintain diversity in your community

- When a tree fails, plant a new one in its place.

For more information on managing your Florida landscape in hurricane season, visit the University of Florida’s Urban Forest Hurricane Recovery page.

by Carrie Stevenson | Jul 5, 2017

This rain garden used stone for a berm and muhly grass as a decorative and functional plant. Photo credit, Jerry Patee

Tropical Storm Cindy’s early arrival soaked northwest Florida this month, followed by even more heavy rain. Homes in low areas and along the rivers flooded and suffered extensive damage. That being said, we are just entering our summer “rainy season,” so it may be wise to spend extra time thinking about adjusting your landscape to handle our typically heavy annual rainfall.

For example, if you have an area in your yard where water always runs after a storm (even a mild one) and washes out your property, you may want to consider a rain garden for that spot. Rain gardens are designed to temporarily hold rainwater and allow it to soak into the ground. However, they are quite different aesthetically from stormwater ponds, because they are planted with water-tolerant trees, shrubs, groundcovers and flowers to provide an attractive alternative to the eroding gully that once inhabited the area! Rain gardens are not “created wetlands,” but landscaped beds that can handle both wet and drier conditions. Many of the plants best suited for rain gardens are also attractive to wildlife, adding another element of beauty to the landscape.

A perfect spot for a rain garden might be downhill from a rain gutter, an area notorious for excess water and erosion. To build a rain garden, the rainwater leaving a particular part of the property (or rooftop), is directed into a gently sloping, 4”-8” deep depression in the ground, the back and sides of which are supported by a berm of earth. The rain garden serves as a catch basin for the water and is usually shaped like a semi-circle. The width of the rain garden depends on the slope and particular site conditions in each yard. Within the area, native plants are placed into loose, sandy soil and mulched. Care should be taken to prevent the garden from having a very deep end where water pools, rather allowing water to spread evenly throughout the basin.

This larger rain garden, or bioretention area, functions as stormwater treatment for a large parking lot in North Carolina. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF / IFAS Extension

Besides reducing a problematic area of the lawn, a rain garden can play an important role in improving water quality. With increasing populations come more pavement, roads, and rooftops, which do almost nothing to absorb or treat stormwater, contributing to the problem. Vegetation and soil do a much better job at handling stormwater. Excess sediment, which can fill in streams and bays, and chemicals from fertilizers and pesticides are just some of the pollutants treated within a rain garden via the natural growth processes of the plants.

A handful of well-known plants that work great in rain gardens include: Louisiana iris, cinnamon fern, buttonbush, Virginia willow, black-eyed Susan, swamp lily, tulip poplar, oakleaf hydrangea, wax myrtle, Florida azalea, river birch, holly, and Southern magnolia. For a complete list of rain garden plants appropriate for our area, visit the “Rain Garden” section of Tallahassee’s “Think about Personal Pollution” website.

For design specifications on building a rain garden, visit the UF Green Building site or contact your local UF IFAS County Extension office.

by Julie McConnell | Jun 2, 2015

Bald cypress growing at the edge of a pond. Photo: Julie McConnell, UF/IFAS

Considering planting a tree in your landscape, but not sure what will do well?

Baldcypress, Taxodium distichum, is one tree you should consider for your Florida landscape. This deciduous conifer is native to North America and is suited to a wide variety of situations, even difficult ones!

Baldcypress is found naturally along stream banks and in swampy areas, but also performs well in dry situations once established. Not many trees can tolerate standing water or flooding situations, but baldcypress is well adapted to these tough spots. In areas that flood or remain wet the tree will form “knees” that project out of the ground and add a beautiful feature – just don’t plan to mow in areas where these develop. Not restricted to wet areas, baldcypress also performs well as a street tree or in limited root zone situations such as parking lot islands.

This tough tree has a soft, delicate leaf texture and interesting globular cones that start out green then turn brown as they mature. The foliage is light green through the spring and summer then turns a coppery gold before the needles fall in the winter. The trunk has a reddish color that is also attractive and will grow branches low to the ground, but can easily be maintained with a clear trunk in a street tree form.

Baldcypress will grow in full sun to part shade and is adapted to all soil types except highly alkaline (over 7.5 pH). Sand, loam, clay, or muck can all sustain this native tree. Few pests bother baldcypress, but it can be affected by bagworms and mites. Mature size can be in excess of 100 feet, but trees typically grow 60-80 feet tall in Florida.

For more information:

Taxodium distichum: Baldcypress

by Carrie Stevenson | May 6, 2015

Just over a year ago, southwest Alabama and northwest Florida experienced a devastating storm that left hundreds without access to their homes and businesses, flooded out and stranded by a hurricane-force storm that didn’t come with the luxury of a week’s warning. Rainfall records in Pensacola go back to 1879, and the April 29-30 storm broke them all, estimating just over 20 inches over the two days. Not only was the rainfall heavy, but the torrent was high in both velocity and volume—at one point, a mind-boggling 5.68 inches fell in the span of one hour. That’s half the annual rainfall of many cities in California and Texas!

A residential street in Pensacola became a raging river a year ago during the torrential floods, putting dozens of people out of their homes. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson UF/IFAS Extension.

With every dark storm cloud comes a silver lining, though, and just like the millions pumped into our regional economy from oil spill-related fines, the April 2014 floods have awakened a “greener” ethic among many residents, business owners, and politicians. According to a study just released by an environmental consulting firm, when asked about infrastructure changes and improvements to flooding and stormwater, attendees at community meetings overwhelmingly preferred “low impact” solutions such as expanded green space, cisterns, rain gardens, and stream restoration to “hard” structures such as bigger underground pipes and more pumps. While traditional engineering infrastructure is still crucial to a community that must maintain roads, stormwater ponds, and buildings, I find it encouraging that residents are interested in trying different techniques that have proven successful both here and in other parts of the world.

The new Langley Bell 4-H Center has four large rain barrels around the building, used to collect roof runoff for landscape design. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson UF/IFAS Extension.

So, how does one prepare for unexpected rain and floods? The first thing is to realize that northwest Florida receives the most annual rainfall (over 60”) of any region of the state, and sometimes it seems to come down all at once. Preparing landscapes to handle both frequent and heavy rains is an important place to start. This article will begin a series of articles delving into those “low-impact” stormwater management techniques that can help lessen the impact of the intense storms we experience here in northwest Florida. Many of these practices, such as creating mulch pathways, harvesting rainwater, and installing shoreline vegetative buffers, can be implemented by individual homeowners and help reduce the impact of flooding on a neighborhood and city-wide level

by Sheila Dunning | Aug 19, 2014

Pine bark beetles are frequent pests of stressed pines in the southern United States. The five most common southern pine bark beetle species include three in the genus Ips. Ips beetles usually colonize only those trees that are already stressed, declining, or fallen due to environmental factors. Infestations may occur in response to drought, root injury, disease, lightning strikes or other stresses including flooding.

Pine bark beetles are frequent pests of stressed pines in the southern United States. The five most common southern pine bark beetle species include three in the genus Ips. Ips beetles usually colonize only those trees that are already stressed, declining, or fallen due to environmental factors. Infestations may occur in response to drought, root injury, disease, lightning strikes or other stresses including flooding.

Ips calligraphus usually attacks the lower portions of stumps, trunks and large limbs greater than 4” in diameter. Early signs of attack include the accumulation of reddish-brown boring dust on the bark, nearby cobwebs or understory foliage. Ips calligraphus can complete their life cycles within 25 days during the summer and can produce eight generations per year in Florida. Newly-emerged adults can fly as far as four miles in their first dispersal to find a new host tree, whichever one is the most stressed.

Most trees are not well adapted to saturated soil conditions. With record rainfall this past April, the ground became inundated with water. When the root environment is dramatically changed by excess moisture, especially during the growing season, a tree’s entire physiology is altered, which may result in the death of the tree.

Water saturated soil reduces the supply of oxygen to tree roots, raises the pH of the soil, and changes the rate of decomposition of organic material; all of which weakens the tree, making it more susceptible to indirect damage from insects and diseases.When the ground becomes completely saturated, a tree’s metabolic processes begin to change very quickly. Photosynthesis is shut down within five hours; the tree is in starvation mode, living on stored starches and unable to make more food. Water moves into and occupies all available pore spaces that once held oxygen. Any remaining oxygen is utilized within three hours. The lack of oxygen prevents the normal decomposition of organic matter which leads to the production and accumulation of toxic gases such as carbon dioxide, methane, hydrogen sulfide and nitrogen oxide. Additionally, within seven days there is a noticeable root growth loss. Roots only develop when soil oxygen levels are at 5% -15%. Over time, the decaying roots are attacked by pathogens. The loss of root mass from decay and fungal attack leaves the tree prone to drought damage. After only two weeks of saturated soil conditions the root crown area can have so many problems that decline and even death are imminent.

When a tree experiences these anaerobic soil conditions it will exhibit symptoms of leaf loss with minimal to no new leaf formation. This usually appears two to eight weeks after the soil dries out again. Many trees will not survive, especially the more juvenile and mature trees. However, well established trees may still decline several years later, if they experience additional stresses such as drought or root disturbance from construction.

There is little that can be done to combat the damage caused by soil saturation. However, it is important to enable the tree to conserve its food supply by resisting pruning and to avoid fertilizing until the following growth season. Removal of mulch will aid in the availability of soil oxygen. Basically, it is a “wait and see” process. While water is essential to the survival of trees, it can also be a detriment when it is excessive, especially for drought tolerant pine species such as Sand Pine, which is prevalent throughout the coastal areas.

For urban and residential landscape trees, preventative strategies to avoid tree stress and therefore reduce the chances of infestation include the following:

1) avoiding compaction of, physical damage to, or pavement over the root zones of pines,

2) providing adequate spacing (15-20ft) between trees,

3) minimizing competing vegetation beneath pines,

4) maintaining proper soil nutrient and pH status and

5) limiting irrigation to established pine areas.

When infested trees are removed, care should be taken to avoid injury to surrounding pines, which could attract the more harmful pine bark beetle species Dendroctonus frontalis, the Southern Pine Bark beetle.

There is no effective way to save an individual tree once it has been successfully colonized by Ips beetles. In some cases, the application of an approved insecticide that coats the entire tree trunk may be warranted to protect high-value landscape trees prior to infestation. UF/IFAS Extension can assist with recommendations.

by Carrie Stevenson | Jun 23, 2014

Since the heavy flooding in late April of this year, many property owners have expressed concern to me and their local government officials about their neighborhood’s vulnerability to flooding. Homes and landscapes are most people’s largest investment, and the damage caused by a major storm can be financially and emotionally devastating.

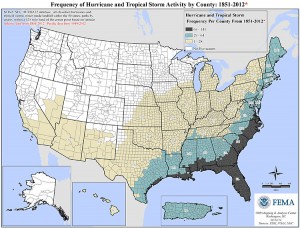

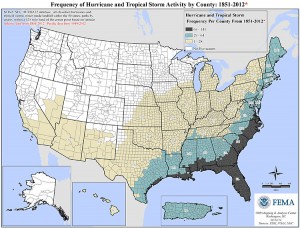

This map shows Florida’s extreme vulnerability to hurricanes and tropical storms, compared with the rest of the country. Graphics courtesy FEMA

To say that Florida is prone to flood is an understatement, at best. Between 1851 and 2012, every county in our state endured between 65 and 141 tropical storms and hurricanes. Many counties average one named storm every 1.1 years. While other states have coastal regions vulnerable to hurricanes, the entire state of Florida lies within FEMA’s highest designation of storm frequency. With hurricane season just beginning and record-breaking flood events in April, it is wise to consider flood insurance. Regular homeowners’ insurance policies do not cover damage related to flooding. Many homeowners go without flood insurance because their home is “high and dry” or “not in a flood zone.” It can be argued, however, that as a Floridian, particularly one in a region of the state with the highest annual average rainfall, you’re in a flood zone—it’s just a matter of whether you’re high or low risk. And, as we’ve seen recently, even those who thought they were low risk could be vulnerable.

Flood insurance is often very inexpensive for those outside of officially designated Special Flood Hazard Areas (think waterfront homes, low-lying property, creek floodplains, and barrier islands). Rates can be as low as $130/year for basic coverage in a low-risk area. It’s simple to get a ballpark figure for potential flood insurance costs by entering your address into a one-step “risk profile” online. According to the National Flood Insurance Program’s (NFIP) website, a quarter of NFIP flood insurance claims and third of Federal Disaster Assistance each year goes to residents outside a mapped high-risk flood zone . When the expenses related to flooding, including removal of flooring, walls, furniture, and damage to plumbing and wiring, are taken into consideration, flood insurance can be a smart investment.

Intense flooding can strike in unexpected locations during heavy rainstorms and tropical storms. This Pensacola street had never experienced serious flood damage prior to April 2014, so most residents did not have flood insurance. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson

Timing is important, too, because a 30-day waiting period is often required before flood insurance coverage kicks in. If you are also looking at additional windstorm insurance, be aware that policies will not be sold if a storm is in the Gulf. It is important to act sooner than later, but if you start now you can have flood and windstorm coverage in place before August and September. Our most severe storms historically occur during these months, after the Gulf has had all summer to warm up.

To purchase flood insurance, contact your local agent, find an agent online at www.floodsmart.gov, or call 1-888-379-9531. Be sure to ask exactly what is covered and under what circumstances, as there are many particularities to flood insurance. For up-to-date information on recent changes to the NFIP, please visit Coastal Planning Specialist Thomas Ruppert’s webpage.

Disclosure: The University of Florida/IFAS Extension program cannot make specific recommendations on insurance agents or providers. Please make the best decision for your home and family to prepare for storms and flooding.