by Matthew Orwat | Jan 26, 2017

Now is the time to start planning for a spring garden! There are many different methods of successful gardening but here I’d like to discuss raised bed gardening.

Now is the time to start planning for a spring garden! There are many different methods of successful gardening but here I’d like to discuss raised bed gardening.

A few advantages of raised beds:

- Raised bed gardens provide an opportunity to bring the family together for some quality time. Add ways that you can enjoy the time with your spouse, child or grandchild. This gives you a chance to see the wonder on their faces as the plants sprout and flourish.

- Share the joy as you smell the flowers and pick the fruit.

- Provide a bouquet for the table as you add an item from the garden to your family meal.

A special kind of raised bed garden, known as an enabling garden, provides individuals needing assistance a way to garden with ease. Many have the impression that building such a garden is expensive, but it is not much more expensive or difficult than building a raised bed garden on the ground. First, begin by trimming and framing a raised bed garden just as you would for a ground level raised bed.

Materials

- 2 – (2X8) boards 14 foot long (treated or cedar)

- 2 – 2 ½ foot end pieces trimmed from a 2×8 board (treated or cedar)

- Central brace board trimmed to fit the inside of the bed

- 16 – 3 inch screws

- Table Saw

- Drill

- Extension Cord

- Durable base such as metal screening, lined with permeable weed barrier, attached to the frame securely.

Once it is made, raise it to the desired level by placing it on cinder blocks. Add enough soil or compost to mound slightly higher than the lumber. Make sure the compost is well rotted, or use sterile potting soil. Don’t use soil from the garden since it may contain root diseases. Smooth out media evenly. Purchase a drip hose or line and run back and forth over the center area. Young plants will not have a large root so make sure the irrigation delivers adequate water to the entire bed.

Many different vegetables herbs can be grown in raised beds but peppers, squash, eggplant, cherry tomatoes, basil, thyme, oregano and mint make excellent choices for a spring raised bed. Happy Gardening !

by Matthew Orwat | Jan 26, 2017

by Carrie Stevenson | Jan 17, 2017

Arbor Day has a 145-year history, started in Nebraska by a nature-loving newspaper editor named J. Sterling Morton who recognized the many valuable services trees provide. The first Arbor Day was such a big success that Mr. Morton’s idea quickly spread nationwide–particularly with children planting trees on school grounds and caring for them throughout the year. Now, Arbor Day is celebrated around the world in more than 30 countries, including every continent but Antarctica. We humans often form emotional attachments to trees, planting them at the beginning of a marriage, birth of a child, or death of a loved one. Trees have tremendous symbolic value within cultures and religions worldwide, so it only makes sense that people around the world have embraced the idea of celebrating a holiday focused solely on trees.

Ancient trees like this live oak have an important place in our cultural history. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson

In addition to their aesthetic beauty and valuable shade in the hot summers, trees provide countless benefits: wood and paper products, nut and fruit production, wildlife habitat, stormwater uptake, soil stabilization, carbon dioxide intake, and oxygen production. New research is even showing that trees can communicate throughout a forest, sharing “information” and nutrients through a deeply connected network of roots and fungi that can increase the resiliency of an entire forest population. And if you’re curious of the actual dollar value of a single tree, the handy online calculator at TreeBenefits.com can give you an approximate lifetime value of a one growing in your own backyard.

While national Arbor Day is held the last Friday in April, Arbor Day in Florida is always the third Friday of January. Due to our geographical location further south than most of the country, our primary planting season is during our relatively mild winters. Trees have the opportunity during cooler months to establish roots without the high demands of the warm growing season in spring and summer.

To commemorate Arbor Day, many local communities will host tree giveaways, plantings, and public ceremonies. In the western Panhandle, the Florida Forest Service, UF/IFAS Extension, and local municipalities have partnered for several events, listed here. As the Chinese proverb goes, “The best time to plant a tree was twenty years ago. The second best time is now.”

For more information on local Arbor Day events and tree giveaways in your area, contact your local Extension Office or County Forester!

by Mark Tancig | Oct 26, 2016

Growing wildflowers is great for pollinators and for you! Credit: UF/IFAS

With fall weather finally giving us a break from the heat of summer, this is the perfect time for North Florida residents to get outside and try their hands at gardening. Not only is gardening rewarding for the beautiful flowers or tasty vegetables produced, but just getting outside and spending time with nature is good for the soul.

The idea that being outside and gardening is good for you isn’t just anecdotal or common sense information. Scientific research shows that people who spend time outdoors are more healthful. Some of the documented case studies go way back. Dr. Benjamin Rush, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, showed that gardening improved the well-being of mentally ill patients. One of the most famous and more recent studies was done by Roger Ulrich in the 1980’s. This study demonstrated that patients with views of trees spent less time in the hospital and requested less pain medication. Otherwise, they had the same ailment, nurses, and room setup.

Physical, social, psychological, and cognitive health factors can all be improved through gardening. Improving psychological health is one of the major benefits of gardening and can be especially useful as we near the end of the election cycle or watch too many TV news programs. Gardening has been shown to reduce stress, anxiety, and tension, which can contribute to high blood pressure, heart disease, obesity, diabetes, and generally feeling miserable. More information regarding the health benefits of gardening can be found in the EDIS Publication Horticultural Therapy (www.edis.ifas.ufl.edu).

Growing vegetables can fill your belly and reduce your stress!

If you would like to de-stress through gardening but are not sure of how to get started, are new to the area, or need a little extra explanation about something you would like to try, the folks at your local UF/IFAS Extension Office are here for you. They offer a variety of educational programs for the beginner, on up to the advanced green thumbs. You can contact them in person or visit the local County Extension webpages and Facebook pages to find out more information about upcoming programs.

In addition to helping you relax through gardening, the topics discussed at UF/IFAS Extension programs can help you save money, eat healthier, and help conserve our natural resources. So not only will you feel better but you could also make the Earth feel better. That helps us all out!

by Daniel J. Leonard | Sep 22, 2016

One of the most overlooked aspects of landscape design, particularly on DIY projects, is the idea of enhancing the architecture of your home by using plants that echo the shapes and features of the structure. The use of proper plant material not only shows off a home’s exterior beauty and increases curb appeal but often will translate into a significant boost in resale value! On site visits, I all too often encounter beautiful homes whose curb appeal potential is squashed due to poor plant selection. For example, how many times have you seen the ranch-style home with too-large Indica Azaleas across the foundation that are reaching for the eaves?

UF/IFAS File Photo.

Using plants to echo architecture is a pertinent topic for me as I just purchased a beautiful historic home in Walton County. This is a situation that could easily be ruined through improper plant selection. However, I’m going to try my best to use plants that enhance, not detract from, the architecture of the home. Here are a few very common architectural elements that happen to be present in my house and some easy planting tips to bring out the best in them:

- A steeply pitched roof and tall, narrow profile. A situation like this calls for the installation of a tight, upright shrub or tree to frame and echo the corner of the home. I am obeying this rule by planting a ‘Sioux’ crapemyrtle, a narrow, upright cultivar growing to 20’ and sporting flaming pink flowers. Some other plant options to consider installing: Ilex x attenuata ‘Savannah’ and other cultivars, ‘Apalachee’ crapemyrtle (lavender Flowers with cinnamon bark), ‘Brodie’ or ‘Spartan’ juniper (upright cultivars), ‘Little Gem’ magnolia. There are even a few selections of live oak such as ‘Highrise’, ‘Skyclimber’, etc. that fit the bill!

- Large, open front porch. We southerners love our front porch sitting, so don’t cover it up by planting large growing shrubs in front of it! Instead, plant a low growing, maintenance free ornamental grass or shrub! I decided to go with an airy, native look and fill the bed under my porch with pink muhly grass (Muhlenbergia capillaris). Here are a few other great options for a low growing plant to show off your porch: ‘Purple Pixie’ loropetalum (a new introduction from the Southern Living Plant Collection), dwarf Fakahatchee grass (an underused native), Indian hawthorne (overplanted but still effective), ‘Firepower’ nandina or one of its newer cousins (bulletproof with good fall color), ‘Soft Caress’ mahonia (elegant selection for a shady bed), holly fern (low growing evergreen fern for a shady area).

- Long, bare walls. Let’s face it, a blank wall is not visually pleasing and bare walls can actually act as a heat sink during our long summer afternoons! To break up the monotony of a bare wall and provide some shading for cooling purposes, mix plants of different heights and textures, even add a small tree or two! Here are a few reminders when landscaping to bring interest to a bare wall: Plant the taller plants (larger shrubs and small trees) in between windows to get height interest but not block views; use plants with flexible limbs and soft foliage for easy pruning and to make maintenance easier; choose plants with colors that will be compatible with the wall; finally, allow at least a foot or two between the wall and the mature size of your plants for ease of access! The plant choices for this application are endless. Get creative!

Whatever your house’s style may be, remember the above suggestions when planting and watch as your landscape grows to enhance the look and value of your home rather than detract from it! Happy planting!

by Carrie Stevenson | Jul 19, 2016

Florida home and yard. Home, house, stone pavers, walkway, yard, landscaping. UF/IFAS Photo: Tyler Jones

Dr. Ramon Leon, Extension Weed Specialist, West Florida REC, Jay

Last year the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) of the World Health Organization (WHO) classified glyphosate as “probably carcinogenic to humans.” This generated a lot of controversy because the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the European Food Safety Authority, and recently a joint report between the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and WHO concluded that glyphosate is unlikely to be carcinogenic in humans.

As a University of Florida/IFAS Weed Specialist, I have been receiving multiple phone calls and e-mails from homeowners, homeowner associations (HOA), lawn care companies and contractors, municipalities, and county managers requesting a list of herbicides that are “safer” than glyphosate. When I ask them the reason for this particular preference, all of them acknowledged that their concern originated from hearing about the IARC report.

The first point that I always explain to people concerned about this issue is that most of the scientific evidence indicates that glyphosate does not have a higher carcinogenic risk compared to many other substances that they are normally exposed to in their daily activities. The second point is that it is important to continuously monitor how chemicals we use affect our health and the environment in the long run. The IARC report is a reminder that we should keep a close eye on glyphosate, the most widely used herbicide in the world, but it is not necessarily a call to stop using it, because at this point there is no direct evidence that it causes cancer in humans.

Very frequently, regardless of the technical details, many homeowners and citizens in urban areas are considering not using glyphosate in their gardens and landscapes, and they would like to use “safer” herbicides.

What do you mean by “safer?”

If you mean lower risk as a carcinogen, then most herbicides registered for use in urban areas would be acceptable because none of them are considered “probably carcinogenic” by IARC or any other regulatory agency. Therefore, you have multiple options to choose from. However, many of the conversations have lead to the statement, “No, I want something that is less toxic than glyphosate!”

Toxicity in pesticides is predominantly assessed using the lethal dose 50 (LD50), which indicates the amount of a chemical that kills 50% of a reference population of test animals (e.g. mice, rabbits, rats). When the LD50 is high, this means that the chemical has low toxicity, and when the LD50 is low it is considered that toxicity is higher because small amounts of the chemical can cause mortality. Glyphosate has one of the highest LD50s for herbicides. In other words, glyphosate is one of the least toxic herbicides available based on the LD50 standard. Therefore, if we want an alternative herbicide that is less toxic, we do not have any options for urban areas.

What about organic herbicides?

Many people associate “organic” with “safer.” This can be misleading because it depends on how safety is measured. For example, there are multiple organic herbicides that are considered to have the same or even higher toxicity when compared with glyphosate, because many of them have irritant and corrosive properties. Furthermore, organic herbicides have dramatically different herbicidal properties that make them unlikely alternatives to effectively replace glyphosate.

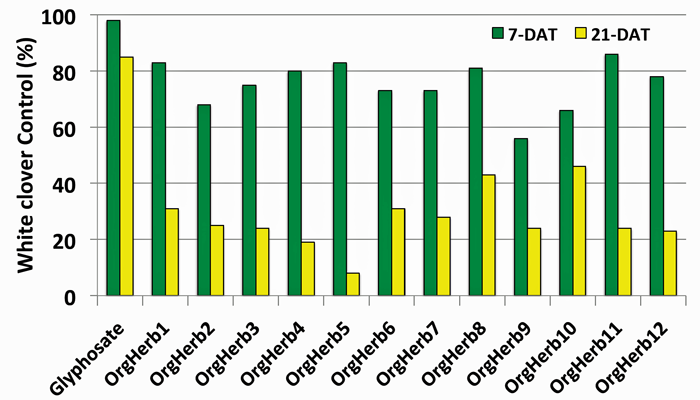

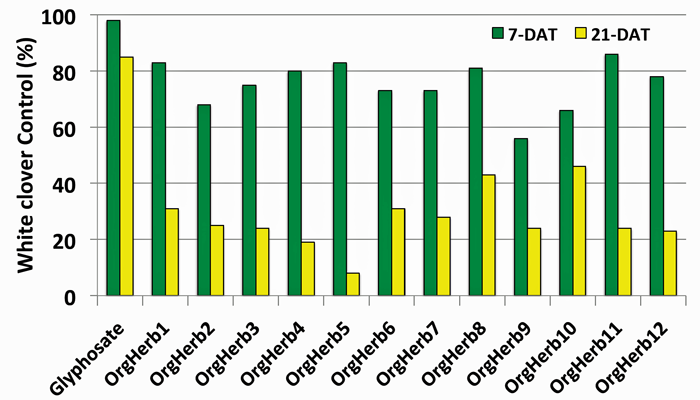

Glyphosate has one of the broadest spectrums of control, so it kills many different weed species effectively. Also, glyphosate works systemically. This means that it is absorbed by leaves and then moves inside the plant to growing points, roots, and other propagating structures. This systemic effect increases the ability to kill relatively large plants. In contrast, the majority of organic herbicides have a contact effect, so they only kill the tissue they touch without being able to move inside the plant. Therefore, they are effective at killing very small plants (<2 inches tall). Large plants can suffer leaf burning after treatment with organic herbicides, and if the application is done properly, the user will see a lot of control shortly after the application (Fig. 1). However, the plants will soon recover and the control level will decrease because, unlike plants treated with systemic herbicides, they can produce new growth from tissues that were not directly expose to the herbicide.

Figure 1. White clover (4 inches tall) control after treatment with glyphosate and twelve different organic herbicides based on natural oil extracts from plants. The green bars represent the level of control 7 days after treatment (DAT) and the yellow bars indicate control 21 DAT.

Considering the lack of alternatives to replace glyphosate, if you want to stop using this herbicide, and you do not want to use any other synthetic herbicides, because their toxicity might be higher, then you need to recognize that weed management will be more challenging. It is unfair to ask lawn care companies or members of HOAs to stop using the tools they have to control weeds and yet expect “weed free” lawns, gardens, and landscapes. Controlling weeds in these scenarios without glyphosate and other synthetic herbicides will require more intensive use of mechanical control approaches and hand weeding. Also, if relying on organic herbicides, these herbicides will have to be frequently applied (probably once or twice a week) in order to kill the weeds at the right time (before they get too big). Also, all these activities will increase weed control costs and the results will likely be not as satisfactory. Thus, you might end up paying more to have lawns and landscapes that will have more weeds escaping control. If this is not acceptable to you, then you probably should be more open to consider the weed control tools we have available. Also, you should be more vigilant about what are the appropriate ways to use them to minimize their risks to humans and the environment, while obtaining the benefits that you are seeking. Otherwise, you should get used to seeing more weeds in the landscape, and to be fair… this might not be as bad as some people think.

Now is the time to start planning for a spring garden! There are many different methods of successful gardening but here I’d like to discuss raised bed gardening.

Now is the time to start planning for a spring garden! There are many different methods of successful gardening but here I’d like to discuss raised bed gardening.