by Beth Bolles | Oct 29, 2018

As Hurricane Michael was barreling through the Panhandle region, wasp populations were at their highest of the year. Winds and flooding destroyed many of the nests of paper wasps, hornets, and yellow jackets and now wasps may be aggressive as they defend themselves or remnants of their nests. All are capable of multiple stings that are very painful. It is very likely that you will encounter stinging wasps as they scavenge for food and water, as well as seek shelter among debris and exposed trash.

Many people are stung by paper wasps after storms. They are not attracted to traps.

Here are a few pointers to help deal with stinging wasps.

- Try not to swat at wasps flying around or landing on you. You may be less likely to receive a sting if you can flick them off.

- Some wasps are attracted to the sap from broken or recently cut trees. Look before you reach. Wear gloves and other protective clothing when moving debris in case you disturb foraging or nesting activities.

- Wasps are also attracted to sugars and water. Try your best to keep food and drink cans covered. Completely close garbage containers or bags that contain food debris.

- Repellents are not effective against wasps. There are pesticides labeled to spray on smaller paper wasp nests if you find one in a spot close to people’s activity. These are usually aerosol pyrethroids or pyrethrins. Make sure you read the label carefully and use the product as directed.

- Do not use non labeled products like gasoline to manage wasps. This is not only illegal but can be dangerous to yourself and the environment.

- There are traps for yellowjackets that you may purchase or make. These only manage those wasps flying around, not any remaining in a ground nest.

Here is a Do It Yourself Yellowjacket trap from UF IFAS Extension.

- Cut the top 1/3 off your 2 liter bottle so that you have 2 pieces.

- Add a bait (fermenting fruit or beer) to the bottom of the plastic bottle.

- Invert the top portion of the bottle into the base, forming a funnel.

- Hang or place traps so they are about 4 to 5 feet above the ground. For safety, place them away from people.

A homemade trap to catch yellowjackets. Photo by Alison Zulyniak

by Mary Salinas | Oct 20, 2018

A natural disaster such as Hurricane Michael can cause excess standing water which leads nuisance mosquito populations to greatly increase. Floodwater mosquitoes lay their eggs in the moist soil. Amazingly, the eggs survive even when the soil dries out. When the eggs in soil once again have consistent moisture, they hatch! One female mosquito may lay up to 200 eggs per batch . Standing water should be reduced as mush as possible to prevent mosquitoes from developing.

You should protect yourself by using an insect repellant (following all label instructions) with any of these active ingredients or using one of the other strategies:

- DEET

- Picaridin

- Oil of lemon eucalyptus

- Para-menthane diol

- IR3535

- An alternative is to wear long-sleeved shirts and pants – although that’s tough in our hot weather

- Wear clothing that is pre-treated with permethrin or apply a permethrin product to your clothes, but not your skin!

- Avoid getting bitten while you sleep by choosing a place with air conditioning or screens on windows and doors or sleep under a mosquito bed net.

Now let’s talk about mosquito control in your own landscape.

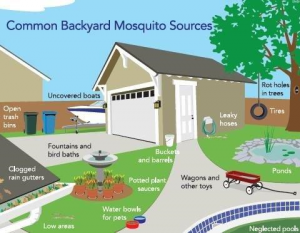

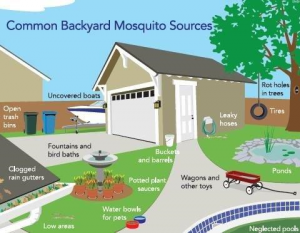

Let’s first explore what kind of environment in your landscape and around your home is friendly to the proliferation of mosquitoes. Adult mosquitoes lay their eggs on or very near water that is still or stagnant. That is because the larvae live in the water but have to come to the surface regularly to breeze. The small delicate larvae need the water surface to be still in order to surface and breathe. Water that is continually moving or flowing inhibits mosquito populations.

Look around your home and landscape for these possible sites of still water that can be excellent mosquito breeding grounds:

- bird baths

- potted plant saucers

- pet dishes

- old tires

- ponds

- roof gutters

- tarps over boats or recreational vehicles

- rain barrels (screen mesh over the opening will prevent females from laying their eggs)

- bromeliads (they hold water in their central cup or leaf axils)

- any other structure that will hold even a small amount of water (I even had them on a heating mat in a greenhouse that had very shallow puddles of water!)

You may want to rid yourself of some of these sources of standing water or empty them every three to four days. What if you have bromeliads, a pond or some other standing water and you want to keep them and yet control mosquitoes? There is an environmentally responsible solution. Some bacteria, Bacillus thuringiensis ssp. israelensis or Bacillus sphaericus, only infects mosquitoes and other close relatives like gnats and blackflies and is harmless to all other organisms. Look for products on the market that contain this bacteria.

For more information:

Mosquito Repellents

UF/IFAS Mosquito Information Website

by Matthew Orwat | Sep 13, 2018

Bare limb tips and clusters of webbing in pecan trees are often the first sign that fall is right around the corner.

This webbing is caused by clusters of the larvae of the Fall Webworm (Hyphantria cunea (Drury)) which is often also called Pecan Webworm. “Fall Webworm” is a bit of a misnomer in our region since they are able to strike in spring and summer thanks to our long growing season. They are most noticeable in the fall thanks to cumulative effects of earlier feeding.

The adult form of the fall webworm is a solid white or white and brown spotted moth that emerges in late March through August in southern climates. After mating they lay orderly clusters of green eggs, usually May through August. Soon after emergence, the larvae begin creating silk webs to protect themselves as they voraciously feed on their various host plants, of which Pecan is most common in Northwest Florida gardens.

Although they are capable of defoliating complete trees, especially smaller ones, most seasons they are kept in check by beneficial insects such as the paper wasp. It is beneficial for small orchards or home growers to scout their trees from June through August. If small webs are observed in young trees, it is best to prune them out with a pole saw or pole pruner and dispose of the branch. Pruning of small branches does not harm the tree, but it may be of no benefit to remove small webs in larger trees, if they are being controlled by natural enemies.

Most home gardens don’t have a practical ability to spray for this insect. For homeowners it is difficult to spray for control, due to the cost of the equipment required to get the spray into the tree canopy. If spraying is an option, many insecticides containing spinosad or Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) exist. Both of these products target caterpillars while not harming beneficial insect predators that feed on these worm populations. Several more toxic insecticide products exist that will control fall webworm, but they often exacerbate insect problems by killing off beneficial insects that might be controlling other insect pests.

Most home gardens don’t have a practical ability to spray for this insect. For homeowners it is difficult to spray for control, due to the cost of the equipment required to get the spray into the tree canopy. If spraying is an option, many insecticides containing spinosad or Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) exist. Both of these products target caterpillars while not harming beneficial insect predators that feed on these worm populations. Several more toxic insecticide products exist that will control fall webworm, but they often exacerbate insect problems by killing off beneficial insects that might be controlling other insect pests.

Fall webworm is not usually a serious problem for home gardens. Let natural enemies take care of the problem in most cases.

Supplemental Material:

by Julie McConnell | Aug 29, 2018

In 2016, I wrote an article for Gardening in the Panhandle called “Attract Pollinators with Dotted Horsemint” introducing readers to this tough native plant that supports native pollinators. If you have flowers in your garden, you probably have pollinators and a whole lot of other insects but if you want a plant that lets you observe a really diverse palate of bugs dotted horsemint Monarda punctata.

When I find I have some downtime at home I have a habit of wandering the yard looking for interesting insects. Admittedly, I usually have my phone in hand hoping to get a great photo or video of my arthropod visitors, but it is a productive task, too. As strange as it may sound, I can count this hobby as part of my integrated pest management landscape maintenance strategy – scouting!

My favorite plant to visit on my scouting run is normally not afflicted with pests, but it hosts so many different insects it always gets a stop on my rounds. When dotted horsemint is in full flower it is visited by a lot more than pollinators. I’ve recorded daily visits from assassin bugs, ants, beetles, flies, dragonflies, spiders, thread-waisted wasps, honey bees, butterflies, and moths.

Here’s a photo album of frequent visitors to my dotted horsemint from this summer – enjoy!

by Les Harrison | Aug 10, 2018

Looks, as the old saying goes, can be deceiving. It is a cautionary pronouncement from experience, usually painful and expensive, to serve as a warning to those who follow and hopefully avoid similar complications if they listen.

In most situations a threat in nature can be easily identified and avoided with a little effort. Except for those situations where the careless or clueless individual blunders into problems, a little observation and logic dictates the potential outcome from a close encounter.

Yellow jackets have stingers, so they must stink something. Alligators would not have all those large and pointed teeth unless they needed to bite something.

Those assumptions are easily deduced by anyone who uses even the slightest quantity of judgement and forethought. Unfortunately, there are occasions where the potential agony is disguised by bright colors and a benevolent appearance.

Such is the case with the caterpillar of the Io moth. Automeris io, this insects entomological name, is a large native moth.

This insects’ range extends from south central and maritime Canada to the eastern half of the U.S. It is found in every Florida County, even into the Keys.

The wingspan of this moth can reach an impressive three and a half inches. Males of this species tend to have a slightly brighter appearance than the females.

Both sexes have large eye spot on each hindwing as a defense device. When revealed, the spots appear as the eyes of predatory creature meant to bluff other aggressors into retreating.

Adults of this species live only a week or two, so reproduction is a priority activity. Luckily, at least for the parents, there are plenty of host plants in north Florida.

Oaks, sweetgums, redbuds, and ash are among the choice meal sites for the developing caterpillars. The eggs are commonly laid in clusters of 20 or more and the caterpillars go through five development stages before reaching adulthood.

Unlike the parents which are active almost exclusively at night, the larvae spend their days hidden in the tree leaves they are consuming. These caterpillars are quite animated and active, frequently seen moving inline from one feeding site to another.

Initially orange, they change to a lime green as they mature. They also develop clusters of spine strategically place across their plump bodies.

Photo Caption: The colorful Io moth caterpillar is covered by fragile spines. Each contains a painful venom for anyone who physically contact this insect larvae.

Distinct from their parents’ eyespot bluff, the spines are a serious defense designed to assure the caterpillars reach maturity unmolested by birds or other predators which would otherwise find them a suitable snack option.

Unlike a pit viper which injects venom via a syringe-like fang or a stingray which retains its barb in a venom saturated sheath, this caterpillar’s spines work differently. Each spine contains a sac filled with the defensive solution.

When contact is made with the hollow spines, deliberately or accidentally, the fragile structure breaks and releases the toxin. The pain is almost instantaneous, intense, and can be a serious health treat for those who have an allergic reaction.

Not usually seen on the ground this caterpillar can be encountered on lower limbs, to the detriment of the unlucky individual. The colorful, toy-like appearance hides a very different reality.

To learn more about north Florida’s stinging caterpillars, contact the local UF/IFAS County Extension Office. Click here for contact information.

by Carrie Stevenson | Aug 10, 2018

A Florida Master Naturalist Uplands class visits the highest point in Florida, located in Walton County. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

For many Floridians, gardening is a window into learning the cycles of the natural world. Understanding pollination, distinguishing beneficial insects from harmful ones, creating compost, or knowing what time of year to apply iron supplements are important for a gardener to be successful. While we have our share of campers, hikers, and kayakers, over the years Extension agents have found that some of our best Master Naturalist students are those with fond memories of farming or gardening as children or adults.

If you have always been fascinated by the natural world and how plants, animals, and people interact, you might be a perfect candidate for the Master Naturalist program. Offered periodically in almost every county in Florida, this adult educational course combines classroom sessions with field instruction, typically over a six-week period. At graduation, students present an original project, which may vary from creating an exhibit, a children’s book, or even an environmental non-profit organization.

Master Naturalist students vary in backgrounds from retired military and teachers to park rangers and college students. Many Master Gardeners find the courses a helpful addition to their training, and utilize their newly gained knowledge when working with clientele. At completion, students receive an official Florida Master Naturalist certificate, pin, and patch.

The traditional 40-hour courses cover Upland, Coastal, and Freshwater Wetland habitats, while the newer “special topics” cover Conservation Science, Environmental Interpretation, Habitat Evaluation, and Wildlife Monitoring. A new “restoration” series has begun with the Coastal Restoration class, which kicked off in Escambia and Santa Rosa counties and is currently being taught in Bay. Extension agents will be offering several classes in the Panhandle this fall—check out the FMNP registration site to see when a class will be offered near you!